What can you give me?

The Mortals' "I Want More" was released three decades ago but feels eternal

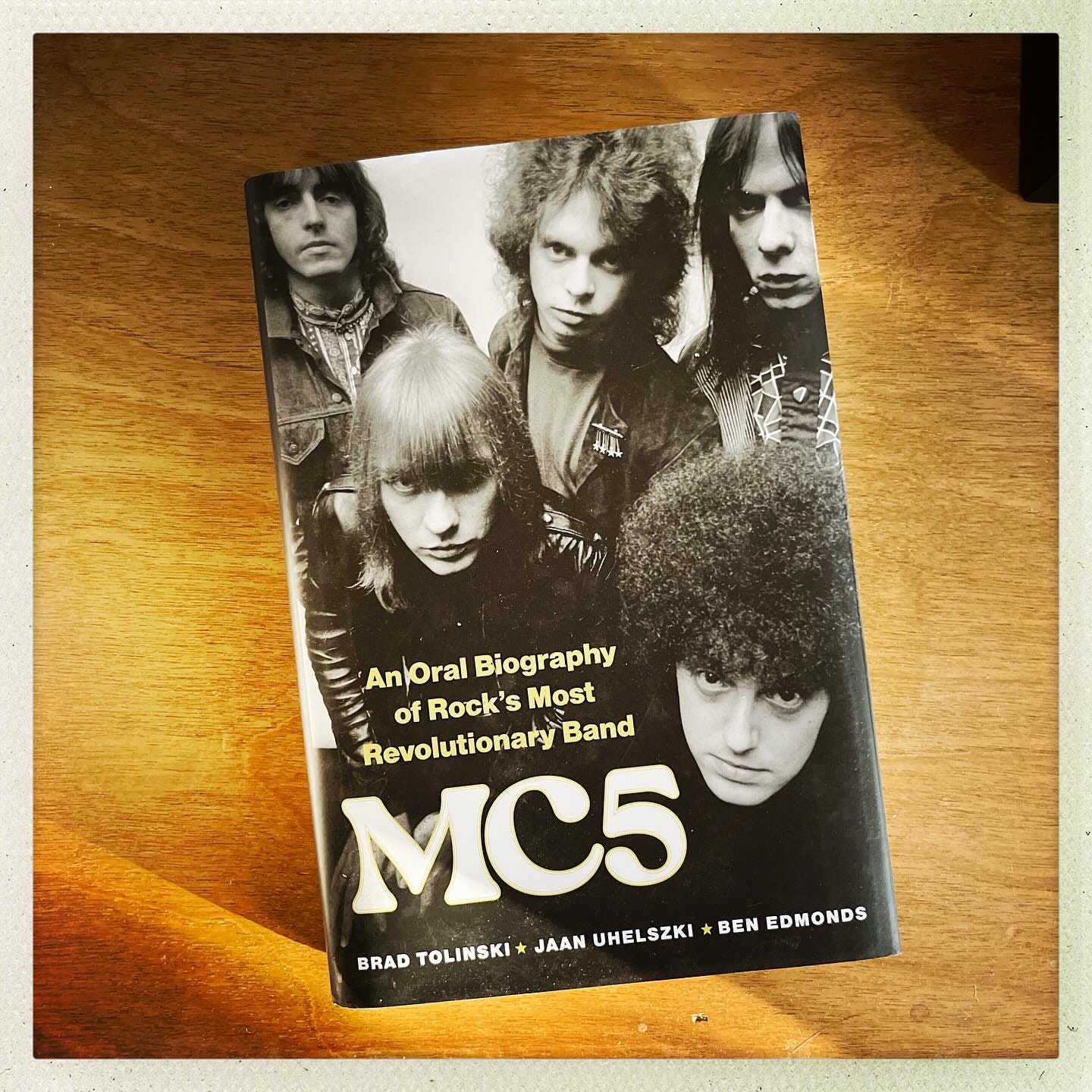

I’ve been reading and thoroughly enjoying Brad Tolinski, Jaan Uhelszki, and Ben Edmonds’s MC5: An Oral Biography of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band. Amidst the terrific stories about their early years and swift, raucous rise as local legends is a fact that confounds me: to a member, the MC5 were disappointed with the performance and sound on their incendiary, righteous debut, Kick Out the Jams.

Complaints abound: the show that was recorded on October 30, 1968 at the Grande in Detroit was an off night for the band, there were badly tuned guitars, bum notes, too many drugs (or not the right kinds), intense nerves, local pressures. Frontman Rob Tyner was required to use two mikes; Wayne Kramer had inexplicably borrowed someone’s guitar. They were wound tight; they couldn’t loosen up. Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton swears that Kramer and drummer Dennis Thompson were out of their minds on acid that night (the two deny this). Memories are scattershot in terms of who promised what when and to whom, but Kramer insists that their record label, Elektra, had assured the band that they’d record several shows and that the band could go in the theatre the next day to fix any excitable errors or overplaying, but that the first night’s recording was issued without any edits. (This has long been disputed.) On the whole, each band member felt that he was not performing up to snuff that night, and that the band’s considerable power had been muted. “We weren’t trying to make perfect music [that night],” Kramer said, “but we knew what we were capable of, and [Kick Out the Jams] was well below the mark.”

(Guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith is sadly, and somewhat inexplicably, absent from MC5. As Dan Epstein recently pointed out, Tyner died three years before Smith and yet Tyner’s everywhere in the book. Was Smith’s taciturn personality the sole reason for his absence? I don’t know, and it’s a real shame that his voice isn’t included, as the omission prevents MC5 from being the standard-bearer biography of the band. I’ll likely have more to say about this nonetheless terrific book in a future No Such Thing As Was.)

I first listened to Kick Out the Jams in its entirety on a cheap tape deck in my p.o.s. ‘72 Datsun as I was driving home from my classes at the University of Maryland sometime in, I think, 1985. I’d recently picked up the cassette, and was hyped to listen to an album start to finish I’d already heard parts of and the legend of which threw a long shadow over many of my favorite rock and roll bands. I distinctly recall tearing out of campus as the overwhelming title track began—I’d already been blown away by Brother J. C. Crawford’s thrilling band introduction and the barreling opening song “Rambling Rose” as I edged my way out of the enormous parking lot. The rest is a blur. It’s a miracle I made it home alive that afternoon.

And so it’s been hard for me to square the band members’ unhappiness with the album with what I hear (and see in my mind’s eye) when I crank it. What does it mean when one person’s disappointment is another’s perfect moment? The opening thirty seconds of “Kick Out the Jams” are so impossibly, righteously thrilling that it’s laughable to me, hundreds of listens later, that the band could’ve possibly hoped for anything more. I wouldn’t change a thing about the performance and sound on my favorite rock and roll live albums—Jerry Lee Lewis’s Live! At the Star-Club, the J. Geils Band’s “Live” Full House, the Ramones’ It’s Alive, Charlie Pickett and the Eggs’ Live at the Button, to name only a few—though I’m sure musicians on each album later winced at something they heard, or didn’t hear, on the record, a botched note, a missed lead, a dragging or overly enthusiastic tempo, shitty vocals.

Keith Richards once remarked that when the Rolling Stones knew that they were being recorded, the show would inevitably be subpar; they should’ve recorded the night before or the night after, he’d joke. Live albums are often doctored in post-production—the news sometimes leaking out years after the fact—but such cosmetic after-care is more a priority for the record labels or the artists and bands then for me: I know that a live show is mercurial, prone to fuck-ups; I usually don’t notice them during shows, or I mock celebrate them in the spirit of the moment. “Mistakes” are par for the course the under lights.

Sometime in the early 1990s I caught the Cincinnati band the Mortals (above) at the Union Bar in Athens, Ohio. The Insect, a local band with whom I was friendly, might’ve opened the show; that would’ve brought me to the gig, since I knew nothing about the Mortals. The show they put on was one of the best I’d seen in years—rollicking, messy, spirited, fun, and loud. At that point they’d released two albums on Estrus, 1992’s Ritual Dimension of Sound and 1994’s Bulletproof, and a handful of singles, but little did I know that night that their recording career was all but over. (They released a rarities compilation, Last Time Around, in 1996 and have sporadically reunited since. In 2022 they released a new studio album Low Value Targets.)

Upstairs in the cramped and crowded Union under a low, sweaty ceiling the band looked anything but finished. Lead guitarist W.J. Grapes darted about the stage consumed by his playing, to the point of distraction, his head down as he set searing lines over the crowd’s head, aided and abetted by the rhythm and occasional lead playing of guitarist Denny Brown. Matt Becher on bass and Mike Grimm on drums held things down, barely, a quaking soundstage on top of which singer Steve “The Tongue” Gatch yelped and moaned, his face obscured by shoulder-length hair, his inner mania made explicit by his nearly obsessive purchase on the songs, many of which I remember sounding dark and scary, full of threat. Some of this felt like an act that night, most of it felt like the real thing.

As I pull wide in memory three decades later, I see how someone who might’ve braved the steep climb up the stairs to the Union’s second floor to catch only a glimpse of the Mortals might’ve guessed that they were mining the soon-to-fade Grunge scene, with their jeans and unkempt tops and long, stringy hair (though on a second glance, every member but Gatch was clean cut). Yet the band was coming at noise from a different angle, updating ‘60s garage stomp-and-pysch (hence Estrus’s interest), trading screeching feedback (of which they were unafraid, in the event) and dark, hooded aggression for hooks and amped-up, punk-styled riffing. Dig the moody “Disintegration,” the pounding wah-wah anthem “I Am Alive,” and the tear through the Del-Vetts’ “Last Time Around.” The hooks sliced through the beery throng at the Union; the eighth notes matched the collective heart rate of the crowd; Grimm rode his ride cymbal in crashing waves. It was one of those shows when it felt as if the floor was tilting, as in a fun house.

Ritual Dimension of Sound was recorded and mixed in December 1991 over a thirty-five hour session at Egg Studios in Seattle, Washington; studio honcho Conrad Uno engineered while Estrus mainstay Richard “Dick” Head produced. Like Head’s work with the equally noisy, ‘60s influenced Mono Men, the Mortals’ album is great sounding: in your face, raw, “live,” with a chest-filling low end and splashy highs. Estrus, like other upstart indie rawk and roll labels of the era, delivered clamorous music that often sounded glued together in a lo-fi, low-budget, “one take only” spirit. One tune from the Mortals show has stayed with me all of these years later. “I Want More,” the lead track on Ritual Dimension of Sound, is one of the great, unheralded rock and roll songs of the 1990s.

It begins with a distorted, aggressively struck guitar chord that prowls menacingly through the opening four bars—we’re stuck in the tiny room with it, getting our bearings—before Grimm’s snare roll busts open the door and the rest of the band comes crashing in, uninvited or not. Staking claim to its territory, the song moves assertively among a few chords. Things sound pretty pissed off even before Gatch enters, snarling. His complaints? His mornings open onto to long swaths of emptiness; it’s always been this way. He gave his sweat, they took his blood, he turned it in to a “livelihood”—such a cheery word but Gatch sings it with hostility. Someone’s to blame for selling him lies and “this emptiness inside my eyes,” for offering him “things that won’t last” that promise no future or past. There’s a cup of bitterness brought his lips. (A key line— “my heart’s a shell of what it was / now all that’s left is a higher road”—elevates things because I don’t know what he’s saying, really. He’s just as likely barking “I don’t know” rather than “A high road,” but the latter’s what I hear sometimes, depending on the weather. Both phrases work for me, desperation leading to the resolve to be better, to search for better, to imagine something better—but that higher ground may be an illusion. I don’t know.)

The fantastic chorus, so gripping and moving to my ears and heart, has consistently delivered the hundreds of times I’ve listened to the song. The simple statement—

I want more, I want more than you can give me

—is eternal in its demands, as brutally elemental as two and two equals four, as this object will fall when I let go of it. I love when a band or a writer lands on a fully felt statement or sentence that could’ve been uttered or written at any time in human history. Here are five kids in a studio in the Pacific Northwest at the cusp of the last decade of the Twentieth century hoarsely singing something that surely kept up a man or woman in bed halfway across the world five hundred years earlier. Whether the singer needs more from a relationship, from his life, from the crowd at The Union—does it matter? Guest backing vocalist Dave Crider of Mono Men emphasizes Gatch’s demand and in response the band hypes the demand, and in fifteen seconds the Mortals have blown all doubts away. I’m brought to attention every time that I listen.

Nothing’s ever solved in rock and roll. It often feels that way to me anyway. Why would be allowed to press “Play” again or lift the needle a second, third, or fourth time? Gatch declines to sing another verse that might move the story forward—resolution? not in this sorry state—so the band does what all great rock and roll bands do, erase the frustrations by continuing to play. “I Want More” ends with a stunning thirty-two bar guitar solo that tries to slash its way out of the bag that Gatch is in, pushing, lurching, swooping, leaping. It closes things down because once the singer’s said all he has to say, and as simply an clearly as he can, there’s nothing left but the sounds that brought him to that moment.

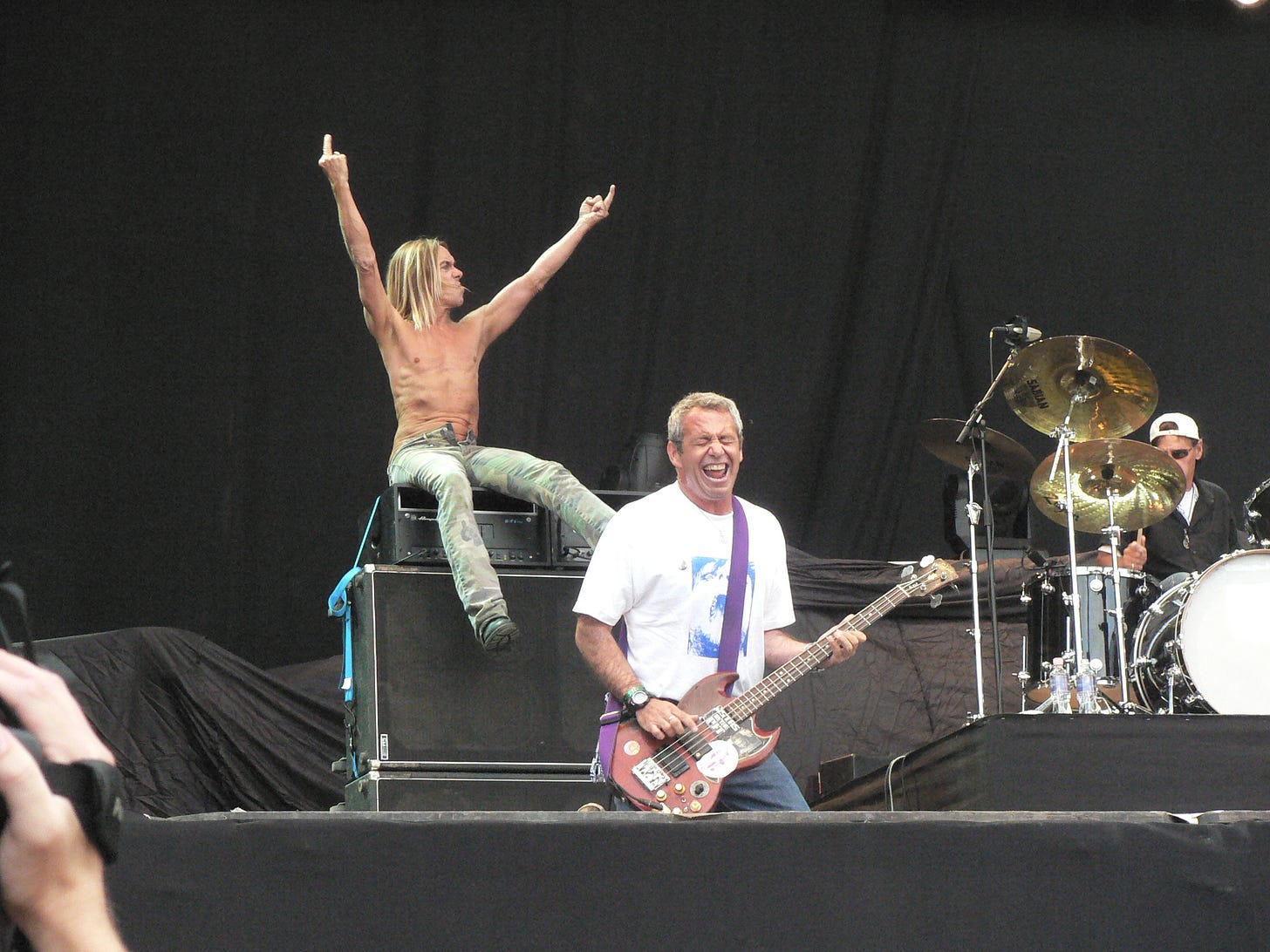

Here’s Iggy Pop, from his careening memoir I Need More, on how rock and roll, specifically the currents that it runs on, laid down track for his escape from Midwest provincial trailer camp life:

…I was in love deeply, was completely hooked on the apparatus itself. Just the sheer presence of electricity in large doses has always made me feel real comfortable and calm, especially the way a very large amplifier with an instrument plugged into it will push air, the way the speakers push air—that’s basically what amps do, they push the air and push me too. And even just the beauty of the microphones appealed to me. And the beat of the drums. It was like, I gotta get out of here, I gotta get out of here. I hate this life! I hate everything about it! I can’t live with it. It hurts me. I feel odd around these people, and music is the only place to hide. The refuge, really.

Did I catch the Mortals on a good night? Were they plugged in to the kind of current that delivered Osterberg from the sticks? Had the Mortals thought it was aa off night, would I have cared, or noticed? I was sent by their performance, the air pushed through their amps pushing me toward the humming epicenter of what the band brought with them, in moments appearing as startled by what they detonated as I was. They showed no evidence of internal friction or road burn. (Here’s a great video from this early 90s’ era, posted on the Mortals Facebook page, of the fellas in their cramped and certainly smelly van between gigs on the long road.) What a band hears and feels onstage can be be graphically far away from what I hear and feel in the crowd. When I listen to “I Want More” I always recall Grapes leaping in their air during some solo, forever poised there.

Photo of the Mortals courtesy Kelsey Grillot

“Iggy Pop Live on the 15th of August, 2006. Budapest, Sziget Festival” via Creative Commons

Great quote from Iggy. And your claim that "nothing's ever solved in rock and roll." Definitely not for people who need certainty or closure or a perfect take.

So good to know someone still gives a shit about The Mortals.