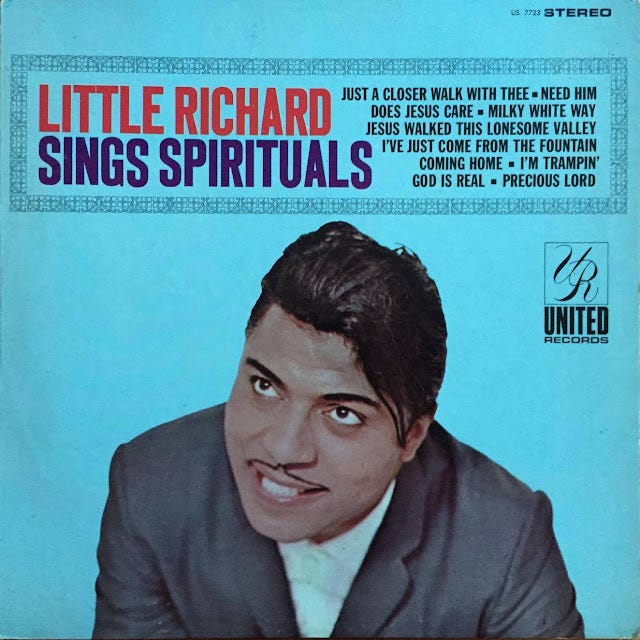

In the late 1950s, Little Richard turned his back on secular rock and roll music and entered Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama, to study theology, reconnect to his evangelical Christian roots, and, to no small degree, continue to reckon with his queerness. At the beginning of the next decade he went into the studio to cut a series of spiritual and gospel standards. The first of these sessions occurred in the fall 1960 in New York City, under the guidance of producer and multi-label owner George Goldner; Richard also recorded spirituals with producer Quincy Jones in New York and Los Angeles. On many of the songs recorded with Goldner, Richard is backed only by organist Herman Stevens, aided and abetted later by dubbed group backing vocals and string sections. Over the next few years the material from these sessions were released on a number of albums, including Pray Along With Little Richard (Top Rank International), Little Richard Sings Freedom Songs (Crown Records), and Little Richard Sings Spirituals (United/Superior Records), the latter of which I recently picked up.

The Goldner tracks are often disparaged. In The Life And Times Of Little Richard, biographer Charles White describes them as “pretty miserable” and “dirgelike,” and down the years his opinion seems to have became holy writ, as it were. I find the recordings, on the whole, genuine and genuinely moving. True, in places Stevens’s organ bizarrely mimics tones usually reserved for a baseball game, and on some cuts Richard sounds—if you can believe this—hesitant. But on standards like “Milky White Way” (words and music by Landers Coleman) and “God Is Real” (Kenneth Morris) Richard really gets inside the words and the beliefs they articulate, and it’s a thrill to hear the octave leaps, graphic falsetto, and signature, aggressively ranging, joyous vocal stylings we associate with “Good Golly Miss Molly” and “Tutti Frutti” in the service of veneration and adoration (which, in his inimitable way, Richard was also doing while going on about Long Tall Sally, but that’s another story).

In the studio with Goldner, he’s relatively decorous, but the devotion, passion, and troubles are real, and whatever complications we’re aware of now—Richard’s intense conflicts across his sexual spectrum (what he called “unnatural affections”) and across the expanse of his God’s mercy and his family’s and church’s dogma—make the performances that much more absorbing. I hear lines like “There are some things I may not know; there are some places I can't go” and, perhaps naively, wonder what knowledge and what places are beyond his ken, if he’s imagining, or not allowing himself to imagine, his own native eroticism and desires as well as grace and secular and spiritual limits. When he sings about walking the milky white way to take his stand, I wonder how he expects to find God’s home, welcoming or censuring?

Within a few years he’d be rocking again, so naturally. The conflicts have never deserted him.