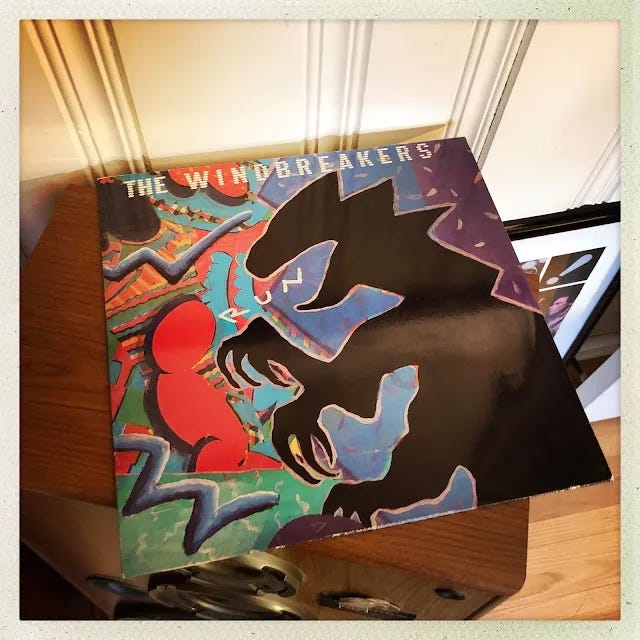

Some songs decline to age well. The music we listen to and obsess over when we're younger doesn't always keep apace with us as we move on. Last night I pulled out the Windbreakers' second album, Run, which was released in 1986, and was happy to discover that it holds up quite well, though I was nervous as the album neared the end. The closer "Nation Of Two" is one of those songs that was nearly unbearable for me to listen to when I was in my early 20s, devastatingly sad as the song is and so settled into my marrow it had become in a bout of depression. The song feels even weightier, and greater, to me now.

Written by Tim Lee—whose songs were always darker and more bitter to my ears than his partner Bobby Sutliff's jangly-if-at-times-melancholy pop tunes, which I also love—"Nation Of Two"'s jaded, world-weary outlook is summarized in its chorus: "In a nation of two, citizenship for few." That discovery looks melodramatic on paper, yet at the time the two lines spoke to me as if they were an ancient text. Embedded in Lee's torturous melody and head-hanging arrangement, the chorus arrives as a brutally sad epiphany, and the song hardly able to bear the weight of it all. I was afraid that I'd be embarrassed, now, by the song's agonies; when the album was released I was having yet another intense period of romantic trouble and, having loved the band's debut album, I snatched up Run and quickly sunk into the abject miseries of "Nation Of Two."

At the time the chorus felt like a flame held to my fingers, and I listened warily—that had, of course, as much to do with my narrow emotional perspective as it did the song's emotional power. The feeling's so melancholy and defeated that it feels as if the song's slowing down in its final third, the musicians surrendering at last to dejectedness; hell, it can barely get out of bed, and it's late afternoon. Yet the moving guitar solo, stridently insisting on lifting us all out of our pathetic, solipsistic blues, yet wounded, also, breathes life back into things, if only to admit defeat at the end. (The songs' five minutes long but, depending on the neediness and self-pity in my mood, could feel as if it was a half hour.) The clarity of decades and a happy life have served not to diminish the song, but to firm it up—it's as powerful a statement of heartache and loneliness to my ears now as it ever was. If it's a bit over the top, well, so are you when you're miserable.

The song's woe-begotten melody and visceral performance—by Lee, Sutliffe, and producer/musician ace Mitch Easter—carry the sentiment into the eternal places where all affecting art resides, a room where a freshly heart-rended twenty-something, someone in their 80s, and I can sit, listening, nodding our heads in identification, scattered across decades and united in song.