Airplanes, flying, records, rotating

The Three O'Clock's magnificent "Jet Fighter" will never touch ground

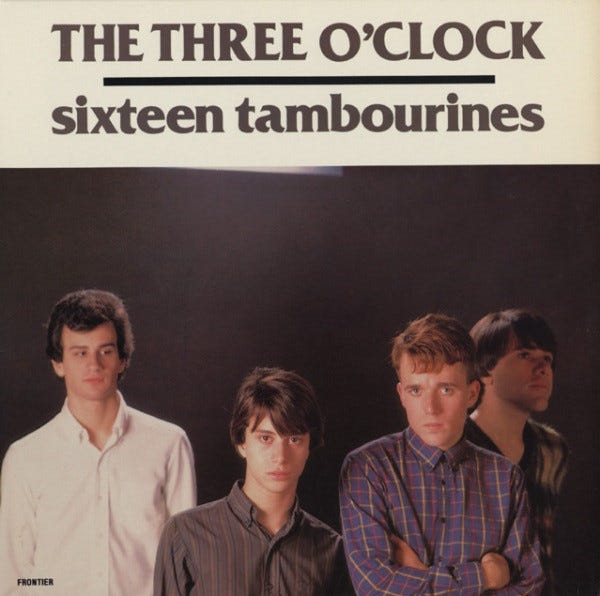

In the latest issue of Ugly Things magazine, Ric Menck writes in his "Call Me Lightning" column about the early records by the Three O'Clock, a seminal band in the so-called "Paisley Underground" scene in southern California in the early 1980s. Menck's piece sent me back to the band's records, which, truthfully, I hadn't pulled out in a while. As usual, Menck's right: "I Go Wild" from the Baroque Hoedown EP does sound like "Revolver-period Beatles on steroids"; Earle Mankey's production updates the band's 1960s leanings without time- and date-stamping the sound; and the band's ecstatic cover of the Easybeats' "Sorry" was a bold choice in that it threw light on an obscure song, much as the Bangles' version of the La De Da's "How Is The Air Up There?" did the same year, ultimately sending so many of us scurrying to find the original on hard-to-find compilations of varying authenticity.

A song can bounce off you, or a song get in and stay there. Circumstance is everything. A shaft of sunlight, a gaze from another, depression or an anxiety attack, grief, a road trip: the contexts are fluid, and unimportant, yet when a song or an album's wavelengths pass through the wavelengths of that particular context, the music changes, and remains eternally alive no matter how many times you listen to it. When I hear the opening bars of "Jet Fighter," the lead track off of the Three O'Clock's debut album Sixteen Tambourines, I'm transported to a particular time and place. I selected "Jet Fighter" as the first song on my first radio show at WMUC at the University of Maryland. The details—3 am, Saturday morning, April, 1985—are only interesting to me. Few memories are more tactile, more dimensional than the moment when, my hands shaking and my heart racing, I spun that song.

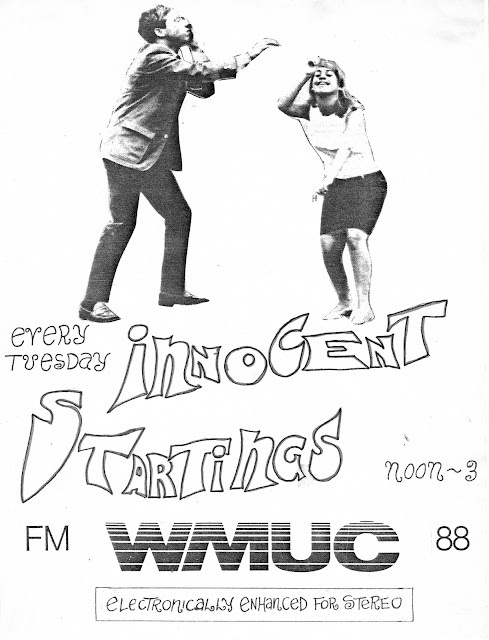

WMUC flexed a robust 15 watts of transmission power, and the joke was that the signal didn't even reach all of the dorms on campus. There'd be the odd story that someone claimed to have picked up 'MUC in Washington D.C. "if the wind was blowing right"—the D.C. line was five or so miles from the station—or while driving somewhere on the Maryland/Virginia Beltway at dawn, yet at the moment I began my first show I didn't care whether two or two million were listening. Watching that turntable rotate, terrified that I wouldn't get the next song cued up—a laughable concern given that I'd memorized my opening set days earlier—swallowing my excitement for some measure of poor-man's (boy's) professionalism, and mentally preparing my first post-set "patter," I was thrilled in the aliveness of the moment, and I was hooked. I'd DJ at 'MUC, eventually moving to prime afternoon slots (see flier below), for my remaining years at college. (I titled my show "Innocent Startings," a ricochet off Colin MacInnes's 1959 Mod novel Absolute Beginners, which I'd read and was determined to love. It seemed clever at the time.)

Several years ago the University of Maryland curated an exhibit devoted to the history of WMUC, and I was startled to find included a photograph of me taken during one of my afternoon shifts (look above, if you must). I vaguely recall a photographer visiting the studio one day; I posed for two or three awkward shots, unsteadily straddling my late-college, collegiate cum Mod look. (Think Mick Talbot's younger brother.) Clearly I was "featured" because the photographer was available only during my slot. In the event, it was a blast nearly four decades later to see those studio rooms again, and the faces of many who I remember fondly.

My friend Don Smith was a DJ at 'MUC the same era I was; he started a year or so after me and so our time overlapped there. After I posted some old fliers on social media he commented on the headiness of our student DJ days, "special times for many reasons, from the camaraderie that we all held in the face of College Society—a lot of which we positioned ourselves for after 7+ years of 'Slobs vs Jocks' college movies, as well as the legitimate love of the music," he remarked. "And secondly, for me, was the sense at the time that our places in the future world could be endless."

Nobody knew what the future would hold and that's something really special about being 18, 19, 20, 21- your future opportunities are wide open and don't begin to narrow for years. That summer when the wall fell and all these people I knew went to Prague! We were inventing our own rules without the fences of the past. I think back to the times of interviewing Kurt Cobain and Björk or giving away tickets to Dave Chappelle and Wanda Sykes at the Greenbelt Comedy Club and knowing people would be big, but not really knowing how to actually get there....

"We were a crucible of 'all that was cool' around that campus," Smith wrote, before adding, "And some of those feelings are bittersweet too."

At age 19, every morning I'd wake up and say to myself, "I can make a difference working in the music business!" At Age 29 I said to myself, "I lost 7 friends to drug overdoses and suicide, I don't ever want to work in music." It was a time when friends in music could be so much but then there was a time when we realized that friends in music isn't a paying job. A few snickers behind someone's back when their major label debut missed the mark, not realizing that the same tiredness I felt with aging grunge wannabes in 1995 also meant I was soon to get passed over for opportunities. But at...1986? The world was our oyster.

Indeed it felt that way, unbound in our cramped, crummy little station above a dining hall. I never had a desire to work in the music business, and the odd interviews I landed with bands were ham-handed at best, but I lived and breathed my sets, mentally running through potential segues while in class, jotting down songs I knew I wanted to play. (One summer I had a jazz show, and I tried my hand at literary programming, too, in "Meter & Frequency," the name courtesy of my then-girlfriend.) More than once during my three-to-six a.m. "graveyard shift" days I'd close a bar with friends in D.C. or Maryland with a shopping bag of albums and 45s at my feet. Then I'd drive to campus and spin records for three hours beneath tottering shelves stuffed with promo carts and albums until the sun came up, drive home, sleep a bit, wake up and head back to campus for classes.

Those were marvelous, indelible times, soundtracked, for me, by "Jet Fighter." I listen again to the song's opening—guitarist Louis Gutierrez's curious, tantalizing sounding, the garage rock cha-cha laid down by drummer Danny Benair, Mike Mariano's twinkling keyboard figure, sounding like nothing less than sunlight glinting off a jet wing, Guitierrez's woosh of an ascending riff, the muttering of an air traffic controller, then Michael Quercio's wispy yet urgent vocals, "Jet fighter man, that's what I am, 'cause tanks go too slow"—and I feel as if I'm ascending, as I did as an excitable eighteen-year old kid, alive on the air, my future world, when I bothered to consider it, indeed feeling boundless as a plane in flight.

Interestingly, what I wasn't hearing in the song then was the blatant ambivalence—the evocative phrases "flying, yet I feel so low"; "protect the land that fills my hand with nothing to show"; "on the day when duty calls I don't think I will go"—in part because the music and the performance are so glorious and exciting, in part because I was tuned to so many emotional confusions at the time I had room for little more. A bit of an anti-anthem, or anyway an anthem to doubt, "Jet Fighter," like all great pop music, elates in itself and complicates things at the same time. Beneath the shimmering glimmer of Mankey's production, some mysteries: who's the singer? Are they off to war? Which war? (Hence the ambivalence?) And who are Mark and Ann? "Come watch me land, I'm sure that they would know"—what would they know?

No matter. Quercio's voice and the words he sang were simply one more instrument in "Jet Fighter," one more moving part in an engine of bliss. It was pitch black outside the window that April early morning of my first DJ show. Inside the studio I was glowing, lit by more than console lights.