Among the pleasures in crate digging is coming across a single that I know nothing about. Last week I was at a favorite joint (Record Wonderland in Roselle, Illinois) wrist-deep in the dollar-45 bin when I was stopped by the bright orange label above. Neither HOB nor Cross Jordan Singers rang a bell, but I took a chance. Back home, I treated the single to a round of Spin Clean and then ran the track through an Audacity carwash. Though not all of the pops and clicks were buffed out, nothing could really interfere with the righteous sound of “This Is All That I Need”—a sound that I didn’t know that I needed until I dropped the needle.

The story of the HOB label is a tale of devotion, in many senses of that word. As related a few years back by robb_k at Soulful Detroit, Carmen Murphy opened a salon, The House of Beauty, on Mack Avenue, and swiftly emerged as “one of the most successful Black business owners during the 1950s in Detroit. She was well connected with her neighbourhood's Southern Baptist church, and in late 1957, she decided she wanted to start a business producing Gospel records. She became friendly with Detroit jazz pianist Jack Surrell, who was a DJ at Radio Station WXYZ. He agreed to be her music company’s main producer and A&R man, and run the music end of the operation.” He added, “His jazz band would be expanded to form their label’s house band. They converted the beauty salon’s large basement into a recording studio with an adjacent practise room.”

In 1958, Murphy and Surell founded House of Beauty Records with the aim of releasing both Gospel and secular singles and albums. Inexperienced at marketing records, they discovered that selling Gospel sides in Detroit was an uphill climb, and in early 1960 Murphy sold the rights to her Gospel recordings to Scepter Records. House of Beauty Records became HOB, and Mike Hanks joined the label as an A&R man and producer. Ever ambitious, Murphy started and nourished other Detroit-based labels including Spartan, Soul, and Starmaker Records, each of which released 45s that sold well locally. (The Barons were the most successful act on Murphy’s labels.) “Near the end of 1963,” robb_k reports, “Ms. Murphy shut down her music operations, and in early 1964 sold the rights to the name ‘Soul Records’ to her friend, Berry Gordy, for $1.00, so he could use it for his newest record label.” The rest is….

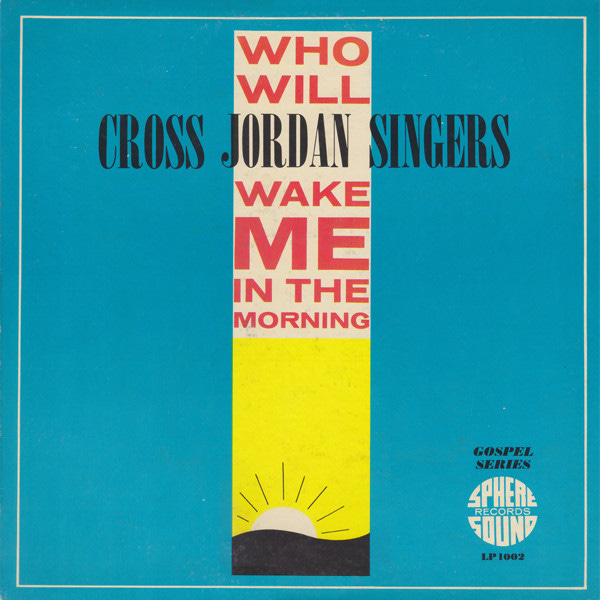

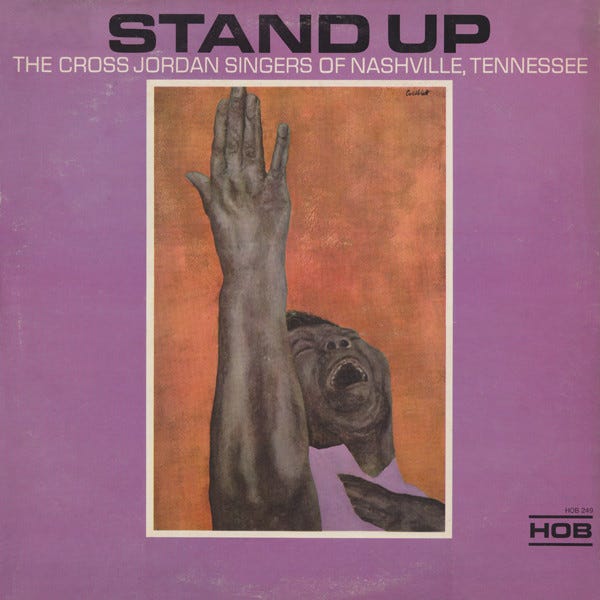

A gospel group, Cross Jordan Singers came together in Nashville, Tennessee sometime in the late 1950s led by the powerful singer Jimmy Milligan. Over a long career they released four albums—Who Will Wake Me In The Morning, Stand Up (both in 1965), Sweet Jesus (1979), and Keep On Praying (1988)—and nine singles from 1959 through 1967. (You can find a modest haul of their work on Spotify and YouTube.) Interestingly, Discogs fails to confirm a release date for “This Is All That I Need”; a search of HOB releases on the site suggests only that the single was issued sometime in 1967 or ‘68. Last fall an intrepid contributor to 45Cat posted a promo copy of the single dated May 31, 1967, securing things. They’d discovered the record “in the estate sale of a Gospel/Christian DJ from the Baltimore/Washington D.C. area in 2023. Nearly all the 45s in the collection were pen dated, presumably by him (handwriting and format is the same) when he received or filed the record.” Great stuff.

The actual release date of “This Is All That I Need” is immaterial, really, as the song’s eternal. The few music sites where you can find information about Cross Jordan Singers organize the group’s sound as “Gospel” under Genre, and as “Funk / Soul” under Style, and it’s just that blend of worship & devotion and rhythm & blues that I hear on “This Is All That I Need,” which was written by Henry Lindsay and John Bowden and produced by Bowden. (As for personnel, your guess is as good as mine. Songwriter and arranger Buddy Franklin penned the liners to Stand Up, noting that, in addition to Milligan on lead vocals, Henry Lindsay, his brother Drew Lindsay, Robert Milton, and Edward Presely sang. They were backed by guitarists Robert Covington and Charles Harris and organist Hampton Carlton—and a regrettably unidentified drummer. As “This Is All That I Need” was recorded a couple of years later, it’s likely that many if not all of the singers and musicians on Stand Up repeated their roles on the 45. But, it’s conjecture.)

Down the decades and out of the air voices come, anyway, whoever’s singing them. But on “This Is All That I Need” there’s some business to take care of before those voices arrive. A jangly guitar riff rings out at the start, covering two bars. The guitarist’s anxious to play, but his sonic pals, a loping bass line and a noodling barrelhouse piano, soon emerge, half-grins plastered on their faces. Something funny happens near the end of the fifth bar. The drummer, who’s just gotten his shoelaces tied, comes bonding out of the house, and the recording’s low end fattens up a bit too, also late. No one’s on time! But for now the whole gang’s gathered on the street. This, the singer declares, looking around, is all that he needs.

If you didn’t live in the Detroit area in the 1960s and didn’t know about the kinds of records that came out on HOB, you’d be forgiven for guessing that the band’s a bunch of well-meaning troublemakers headed down to the park or bar. Then the backing vocalists arrive, harmonizing in true Gospel style, and in the moment you translate those Gospel rhythms, and you know that, nah, we’re heading the other direction I guess, up the block to church. Hope your shoes are shined. Then a Wellll!—or is it a Wowwww!—comes roaring out of Milligan’s throat, dragging the sacred back into the gutter. If Wilson Pickett or Dave Prater are listening, they’re ought to be sweating. We don’t where we’re headed now. And we’re only thirty seconds in.

Milligan commands this song. His voice is both overwhelming and inviting, gruff and raw in its intimacy, all-knowing and prideful in its devotion. I love how he hollers-sings the verses, as if he’s caught your eye out on the street and he’s engaged you in some heavy rap. He’s hard to ignore, or to dodge. “I don’t know how you feel about it,” he shrugs, directly addressing you,

But I know God’s been good to me

You know what I told God?

I’m gonna serve Him ‘till I die

A simple declaration, the last line’s sung and echoed by the backing singers in the chorus at a chord change, a modest gift for the heavens, leading back into the title phrase where things are now made clear: what the singer most needs is not this street nor his mates, but their maker. The second and the third verses offer some dire possibilities and more promises to serve, though in places Milligan’s words are garbled, sometimes chewed in half, by his gruff delivery, which feels now as if it’s gotten loose of him somewhere along the line, humming with a life of its own, separate from the man who’s made it. But Milligan refocuses with a simple statement, one uttered by countless people down the centuries, in both good times and bad: I got it, oh yes I’ve got it.

The “it” Milligan will testify to not only in his native Alabama and adopted Tennessee but in New York and California, up and down the mountains and across bridges, hollering all the while, a full-throated, extolling soul singer. Now the song’s really rocking, its last minute or so riding on waves of joy, and Milligan and his backing singers bring the thing to a raucous close as they call and respond, the sounds ricocheting off of all kinds of things both divine and worldly. In the Cross Jordan Singers’ hands, “It” is clearly Jesus, and yet, especially in the way that the phrase “I got it” is repeated so ecstatically and so powerfully, I also hear Dean Moriarty—he’s just down the block—confessing to Sal Paradise that Dean believes in only three things: the road, God, and It. So what’s “It” beyond God? Timelessness, rebirth, placelessness? (“…you’ll finally get it.” “Get what?” “IT! IT! I’ll tell you—now no time, we have no time now.”)

I “fell away” from the Catholic church decades ago. I wasn’t raised in the tradition of the Gospel church, and over the years when I’ve admired, and often have very much loved, Gospel music, I’ve felt like a spectator of sorts, someone peering through a window at ecstasies and elation, on some days recognizing and identifying, yet never fully participating. But I was baptized twice, once in the Baptismal Font at Saint Andrew the Apostle Church, and once in front of a rec room stereo in suburban Washington D.C.. Forget the tyranny of taxonomy: “This Is All That I Need” is a soul number, grooving R&B, a rock and roll song, street corner stuff, as well as church music. I don’t need to be a pious believer to be moved and elevated by Jimmy Milligan and his fellas’ throaty exhortations to God. The last sixty seconds of Wilson Pickett’s “Land of 1000 Dances” toss me just as high. (Well, higher, if I’m truly confessing.)

What I hear in the grooves of this beat-up 45 are simple but deep-seated affirmations, the joys of plugging in to whatever that something is that’s inside or outside of us that helps us to transcend our lousy world. And what a lousy world we’re in right now. I’m writing this during Black History Month as my country’s elected leaders are, bizarrely and cruelly, stripping away the rights of and assistance to many who’ve been historically marginalized or worse, oppressed and erased. We need all sorts of joy right now. I’m choosing to be grateful for the transcendence of digging through boxes of half-century old 45s in the spirit that I might be graced by whatever it is larger then me that delivers a gem like “This Is All That I Need.” That’s all I need.

See also:

Little Richard is Real

Album cover images via Discogs

One of the great, humbling and horizon-broadening experiences of my life was spending two years as part of an urban Pentecostal church in Kansas City. Sadly, no guitar-driven sanctified R&B, but the genuine expressions of faith and community stick with me (and haunt me) years later.

this generalized topic is one that Mike McGonigal has written about. I love this sound, along with Charlie Jackson and Utah Smith and many others. The whole school of guitar evangelism (to which this is related in a somewhat distant way) is very powerful. You will find (if you have not already) that there were a lot records made like this.