Ask me why

The world lost a wise and idiosyncratic music writer when Ian MacDonald died in 2003

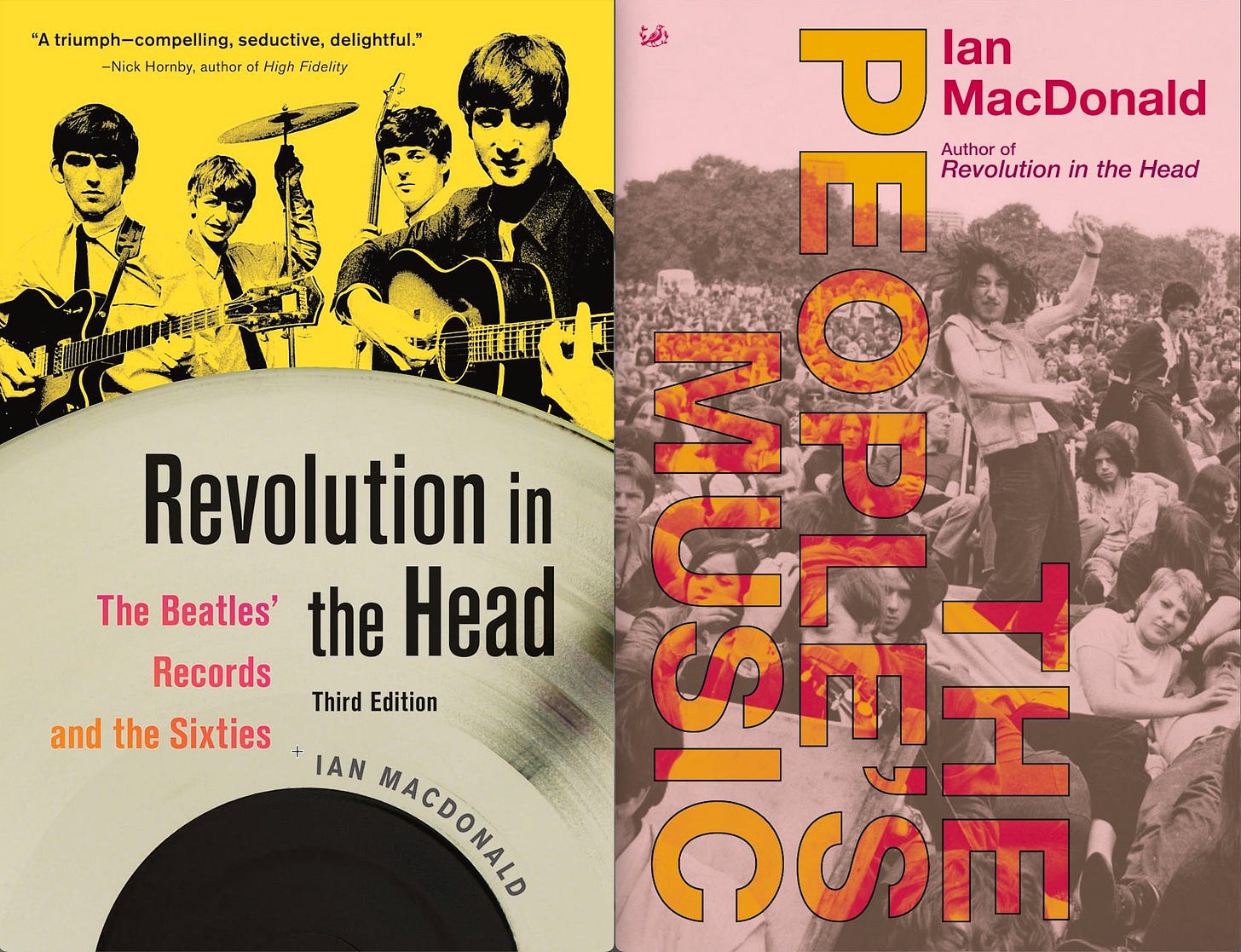

I was introduced to the English writer Ian MacDonald (1948-2003) by his powerfully persuasive Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the 1960s, among the great books of Beatles criticism. (First published in 1994, it was reissued in revised editions in ‘97 and 2005.)

The book has its detractors—more on that below—but on the level of the sentence alone, Revolution in the Head has, to my ears, few competitors. MacDonald’s elegant and sophisticated prose engages as earthy, highly articulate conversation—you always want to respond out loud, to agree or to talk back—issuing from a smart guy eager to communicate and engage, not to dazzle and lecture (though he could do that if he wanted to). His drops eye-opening metaphors in virtually every other sentence, and his gift in characterizing the Beatles’ songs’ moods, and how they’re creatively and technically achieved, startles me every time I read the book, which is often. He’s especially perceptive on the aesthetic and psychological differences among Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison—how their songs bent to their personalities—and how those differences are reflected not only lyrically but musically/formally. The book’s historic sweep is grand and and well-informed—it’s a story about a decade as well as a rock and roll band—and the introduction (“Fabled Foursome, Disappearing Decade”) is a powerful and poignant take not only on the place of pop music in time but on the nature of time itself.

MacDonald cared deeply about popular music (and classical and the plastic arts, too, under different hats), and understood intuitively that music has scored the lives of millions, and is freighted with both personal and cultural meanings. That affection and seriousness of purpose are born out in The People’s Music, published just prior to his death, a book that took me far too long to get to. A miscellany, collecting pieces that MacDonald wrote about mostly 1960s and ‘70s pop, rock, and R&B musicians and bands for Mojo, Uncut, and Arena, and other U.K. magazines, The People’s Music showcases MacDonald’s wide-ranging knowledge and taste, and his personal style. He’s beholden to magazine journalism’s economy of space, and so he doesn’t stretch out as he does in Revolution in the Head, but, forced to three or so pages, as many of these pieces ran, he’s cogent and focused. (The exceptions here are “Wild Mercury: A Tale of Two Dylans,” a lengthy and fantastic essay on Bob Dylan’s interior demons and conflicts, and an equally great and ambitious personal-critical piece on Nick Drake.)

MacDonald never loses his voice, and he’s never afraid to lead with acute, sometimes devastating observations, as in this, on late Cream:

The rest, while undeniably passionate and crushingly powerful, is aesthetically grotesque: a blazing blue furnace of crude banality blown into megalomania by a zillion watts of electricity.

Or this, on Pink Floyd’s post-Syd Barrett music:

...a uniquely stately basic tempo in which melody lines adopted a characteristic wave-like uniformity and chord changes became almost effortful events.

Whether you agree with his arguments or not doesn’t particularly interest MacDonald; he trusts his ears and his heart and his deeply informed grasp of historical context.

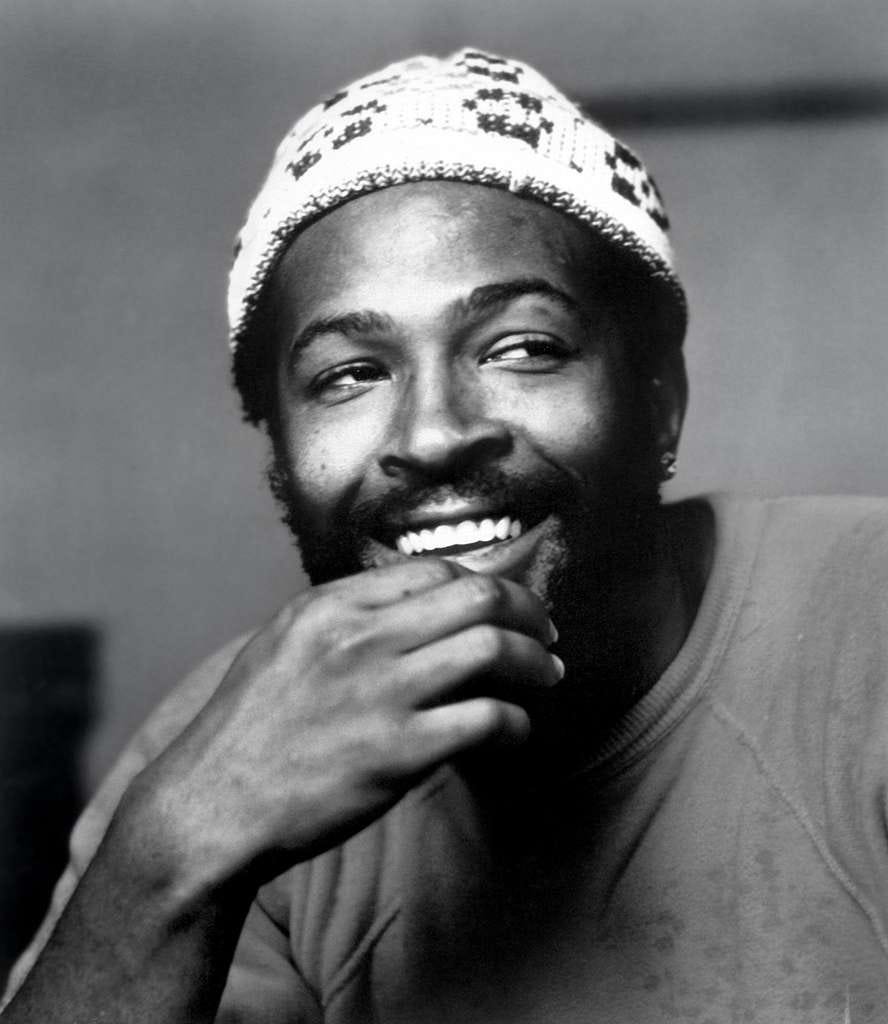

MacDonald’s forthright critical reconsideration of Marvin Gaye’s vexed and ultimately tragic career, in a brief piece snarkily titled “Marvellous Marvin Reconsidered,” is characteristic, written with a blend of affection, respect, and frank disappointment:

Without delving into deep waters, it seems likely that Marvin’s problems boiled down to what medieval divines once condemned as the sin of acedia, or spiritual boredom. His restlessness, even when it led to drug-frazzled rages, was basically inert, characterised by drift. In his recent biography, Trouble Man, Steve Turner suggests that Gaye manoeuvred his father into killing him—one of the most deviously passive methods of suicide ever contrived. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the same passivity mars much of his music. What other artist, after all, spawned so many half-finished or abandoned projects?

Gaye’s landmark 1971 album What’s Going On, MacDonald wrote, was “a record which, while piously elected to the upper echelons of every top 100 albums list, is nevertheless pervaded by an underlying torpor more obvious in his later work.” Many of the tracks “are undeniably original,” yet Gaye’s so-called political lyrics “are trite and often mushily wishful.” MacDonald observes that Gaye’s claim, on the title track of 1973’s Let’s Get It On, “that ‘we’re all sensitive people’ is true to the extent that few of us are completely impermeable, but risible if taken to mean that we’re all equally perceptive and caring about each other. An observant man capable of watching himself washed to and fro by his conflicting desires, Gaye must at heart have been aware of the emptiness of such stuff.”

Gaye, he concludes, “was a beguiling voice worth hearing even when spinning vocal and lyric clichés or effectively singing about nothing at all—which covers a large tranche of his career. The supine coke-fuck aesthetic that governs much of his work will strike future listeners as decadent or prophetic, depending on how history proceeds.” More likely is that “the lushly listless drift of posthumous issues like ‘Walkin’ In The Rain’ and ‘Just Like’ accurately represents their creator’s inner world, wherein ecstasy, melancholy, and ennui were twined in troubled complicity.” I don’t agree with everything MaDonald writes about the great Gaye, but that’s no matter. I am so enamored of MacDonald’s style—erudite yet fluid, too; it swings, in a buttoned-up Englishman’s Cambridge-dropout style—and of the way he recognizes that in pop music the stakes are often high.

In a blurb on the back cover of Revolution in the Head, The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik raved that MacDonald “has ferociously exact ears. He hears things.” Few who take issue with the book dispute that; rather, they’re upset with the many suppositions that MacDonald made about those things that he heard. Some readers roll their eyes at his overly-confident conjectures and overly subjective approach; others have cited errors in his musical analysis. In places, MacDonald writes as if he’d been granted access to a kind of Beatles inner sanctum, yet as well-researched and -informed as the book is, and as knowledgeable a music writer he was, MacDonald was no insider. Some readers have called out gross presumptions on his part, in that he knew more than he possibly could about the band members’ motives and their often private songwriting processes.

A notable critic of Revolution in the Head is one of those very songwriters. In a July 2004 interview in Uncut magazine, Paul McCartney, reacting when the interviewer described Revolution in the Head as compelling, took umbrage. “Well, it might be compelling reading for you. But not for me it isn’t,” he said. “Because I keep finding all the mistakes in it. ‘McCartney did this because of that...’ And I’m sitting there thinking, ‘No, I didn’t.’ Or, ‘John Lennon was out of his head on this when he wrote that.’ No, he wasn’t. I should know because I was fucking there.” McCartney added, “It’s all this received wisdom shit. It’s good that someone like Ian bothered to write a book about us. I’m sure a lot of it is very perceptive. But what do you do when you're me? When someone is telling you what it’s like to be in a room writing ‘A Day In The Life’ and you’re thinking, ‘No, that’s not what it was like at all.’ It can be very enraging, that sort of thing.”

Perhaps perversely, I’m ok with MacDonald’s approach. In fact, I delight in it, even when I strongly disagree with some of his assessments. MacDonald could have played it safe and added a disclaimer of sorts at the front of the book, alerting those readers, who care, about the differences between journalism and conjecture, at the intersection of which MacDonald happily, if mischievously, loiters. (Speculative nonfiction anyone?) Decades after their split, the Beatles were larger than life. The band members were so mythic as to be characters of folklore, defined by and yet paradoxically unbound from time, as much as they were ordinary (ok, extraordinary) men born in northern England in the 1940s. The group lived in MacDonald’s imagination as loudly and colorfully as they lived on their singles and their albums and in confirmable E.M.I. studio logs.

Listening, the pleasure principle kicked in for MacDonald, catnip for any writer: I wonder how this song informed that one…, how this Top 10 R&B hit might’ve influenced Lennon…; how Paul’s tune might’ve answered Lennon’s. MacDonald occasionally softens his arguments with a “possibly” here and a “likely” there, and when he doesn’t, I find his assertions and educated guesses no less edifying, interesting, or fun. I understand that such assumptions bother McCartney, but that’s what you’ve got to live with for writing and recording songs that so fire the imagination and curiosity of millions of delighted, moved strangers. For his part, McCarney told Uncut that by this point he’d “stopped trying [to correct what he perceives to be inaccuracies]…. It got to a point where I realised that I couldn’t go on trying to correct the things that were wrong. Because I wasn’t doing myself any favours.”

Barring a point-by-point takedown from McCartney, whose memory is as fallible as anyone’s, I’ll continue to enjoy MacDonald’s nervy world building, inspired as it was by the joys and pleasures in the music as that music entered popular culture—the air we all breathe.

In The People’s Music, MacDonald’s takes on Lennon and McCartney, the Stones, Chic, the Supremes, Randy Newman, Laura Nyro, the Beach Boys, Lenny Bruce, Love, Simon and Garfunkel, Miles Davis, and many others are equally candid, concise, smart, and stylish (if, admittedly, not always blazing ground that others haven’t covered). There is throughout MacDonald’s work the dismaying thought that since the end of the 1960s it’s been all downhill, culturally and artistically speaking, that in the 21st century we live in a soulless, anti-spiritual, materialist, metronomic sheen of indulgent and shallow posturing, and at times this worldview, which was likely exacerbated by MacDonald’s ongoing clinical depression, leads to unfortunate generalizing on his part. Such as this overreach: “In today’s pleasure-seeking world, introspection holds no appeal and the sixties’ focus on innerness is ignored or derided as a cover for nineties-style chemical hedonism. The truth was otherwise in 1965-9.” The raft of generous, inward seeking, reflective twenty-something writing students I’ve taught down the decades would beg to disagree.

The People’s Music’s title essay is especially crabby; among other complaints, MacDonald asserts that no contemporary artists are worthy of biographies the way their mid-century predecessors were. Absurd! But such overstatement issues from the deep care that MacDonald took in writing truthfully, as he saw (and deeply felt) it. He took the world very personally. In his introduction to The People’s Music, he refers to what others perceive as his critical limitations, acknowledging that the book is simply “one way of looking at modern popular music” and that “there is no definitive viewpoint on pop/rock—only individual angles and private agendas,” adding that his writing “stands or falls by whether it provokes new thoughts or feelings, and its success in doing so is up to the reader to decide.”

“Private agendas” may be MacDonald’s encoded wink to those who are skeptical of his highly personal approach to writing about music and culture. Somedays, his sincerity and fierce intelligence suggest to me that he may have been a prophet of sorts, with whom the rest of will inevitably have to catch up. I’m not sure. But if you care about thoughtful and passionate takes on culture, pop music and rock and roll, and love great sentences that hum with conviction and authority, I recommend that you get some Ian MacDonald in your life. He left his behind too soon.

You might also dig:

Annus mirabilis

“When Sgt. Pepper was released in June, it was a major cultural event,” Ian MacDonald wrote in Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and The Sixties. “Young and old alike were entranced.”

Right now, right now...

In 1967 pop critic Richard Goldstein, in what might charitably be called a minority opinion, laid into the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. A longtime Beatles fan, he was bummed out by the record’s grandiosity (“Like an over-attended child, this album is spoiled”) and disappointed that the Beatles had disconnected themselves from everyday…

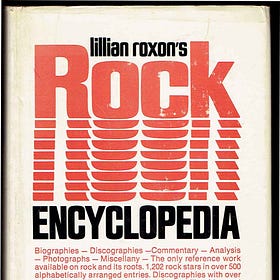

Revisiting Roxon's Rock

Since migrating my old blog over to Substack, I’ll be periodically revisiting and revising some older pieces.

“Marvin Gaye (1973 publicity photo)” via Wikipedia Commons

“The Beatles statue in Liverpool” via Wikipedia Commons

So good you wrote about MacDonald, and so well. I love all he writes, but "Revolution" tops my list of Beatles books. Your quote from him about Cream reminded me of a recent situation in my life: I had to clean the basement (don't ask), so I took down some CDs, including one of Cream's notable songs. I was always a big fan back in the day, but I had to take it off after a few cuts---just a lot of misdirectional guitars and poor singing. So I put on a Joe Henderson album and the basement sparkles! My ears have changed obviously; I'm after form, and that's one thing MacDonald was very good at, taking a simple Bs song and uncovering how grand and complicated it actually is. Regarding Sir P's comments about MacD: I wonder if Paul has weighed in on Ian Leslie's new book and the assumptions it makes. And, one more thought your wonderful post triggered: what about the recent bunch of essays/editorials, etc about how film and lit critics are playing nice about substandard work--everything is a blockbuster, blah blah. Wonder if the same has infected writing about music. And, to conclude, MacD's closing graph in his review of "Gaucho": "...Dan's funniest album is also their most urbane. A gem in the trash can of Californian entropy, a ray of coherent light amid LA's louch neon, a chuckling oxygen nozzle dropped through the smog of modern nothingness..." I wish there was one good and solid book about Steely Dan like "Revolution in the Head." Rock on, Joe.

As you said, Joe, at the level of the sentence, MacDonald was a fabulous writer, and the fact he ‘interpreted’ so much, which was, Paul, his job as a critic, and so interestingly, makes him an invaluable asset where the Fabs are concerned.

McCartney has always been too thin-skinned and too invested in himself; we don’t care if MacDonald’s suppositions don’t ring true to you, Paul, because he’s writing for us, not you. And he’s doing it brilliantly, just as you, Sir Paul, once did yourself.

Lovely and considered piece, Joe, and a welcome addition to the work of shining a brighter light on the late, great Ian MacDonald’s work.

PS He was, or so I seem to remember reading somewhere, working on a similar book to ‘Revolution…’ about Bowie. Now, that would have been a treat!