Attack!!

DMZ, the Fluid, and Edwin Starr have fun with the Kinks, the Troggs, and Titus Turner

In Play This Book Loud: Noisy Essays, my new book out this May from University of Georgia Press, I write about cover songs:

A song is covered for any number of commercial, audience-pleasing, or personal-stake reasons. A singer might announce, onstage or in front of his bedroom mirror, “This song matters to me because. . .” Sometimes a musician covers a song to learn something technical inside of the playing, in the odd chord or tricky time changes. Sometimes a musician covers a song she’s loved since she was a child and first heard on the radio or in her dad’s record or cd collection; sometimes a musician covers a song dictated by his manager or record label. A song has an opening: you climb in. Or a song casts a silhouette: sometimes you step inside of it and you’re home.

Or sometimes you just want to tear it up and have some kicks. Here’s a story about three songs that were airlifted from one era into another, and took a sonic and cultural trip.

DMZ was a bit of an oddity, a rock and roll band that history has condemned to the fringes of late Seventies punk. Hailing from Boston didn’t necessarily help the group’s media exposure, dwarfed as the city was by the media wattage pulsating out of Manhattan, London, and Los Angeles. DMZ was also a hard group to box up: a punk band with two guitarists and an organ player? They released an EP on Bomp in 1977 produced by Craig Leon, and a self-titled album on Sire a year later produced by Flo and Eddie that hasn’t aged very well; the production brutally squashed the band’s dynamics, though the songs are sturdy. After DMZ metamorphosed into Lyres at the end of the decade, various EPs and singles appeared that collected stray studio tracks that DMZ had cut during their brief existence. Some—“The First Time Is The Best Time,” “Boy From Nowhere,” a sneering cover of "Teenage Head”—are pretty great.

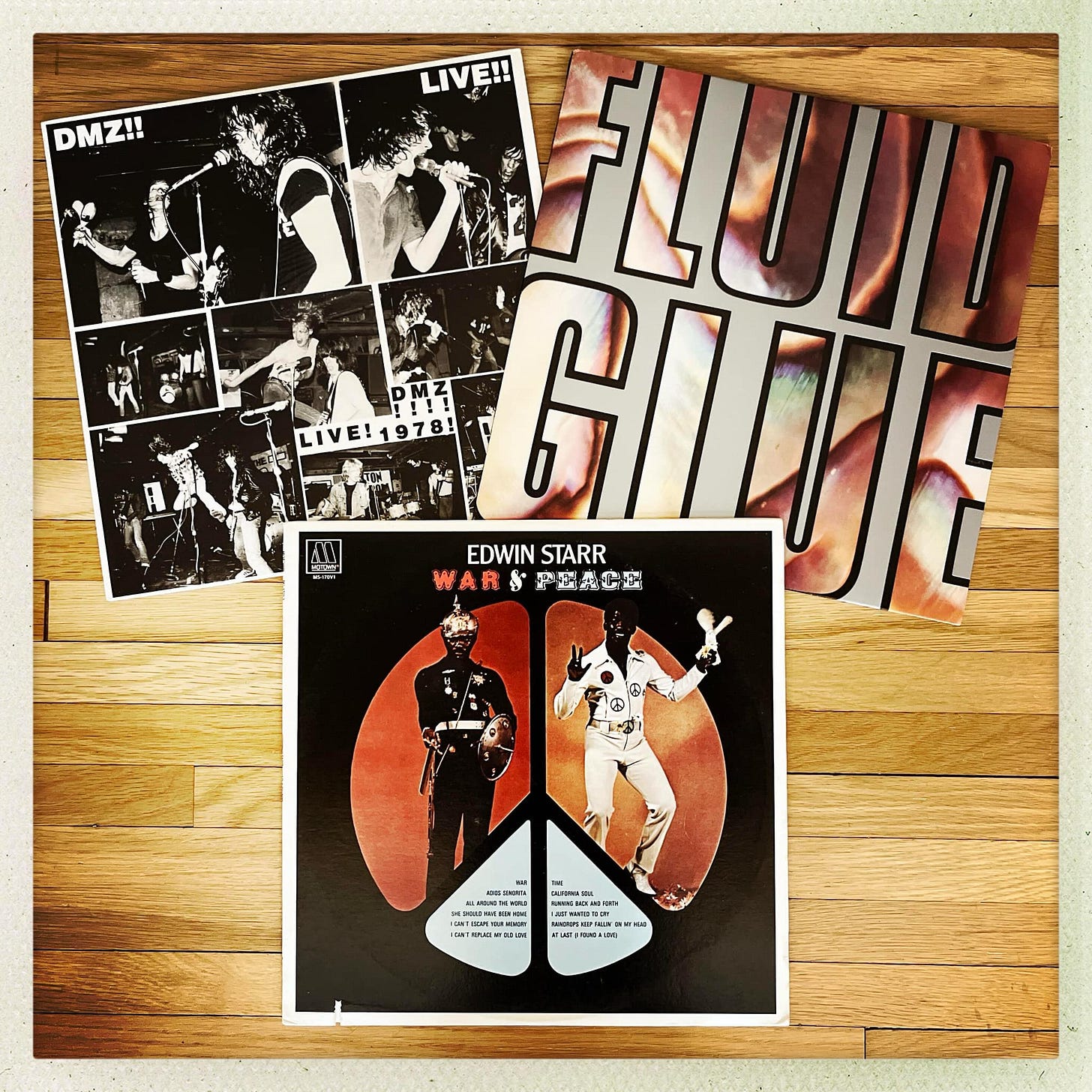

My favorite DMZ document may well be a June 2, 1978 show taped at Barnaby’s, a tiny, long-gone joint in Methuen, Massachusetts, about thirty miles north of Boston. As recorded by Arg! Arf! label founder Erik Lindgren, the tapes languished in the cans until 1986, when venerable Crypt Records issued them as the full-length album DMZ!! Live!! 1978!!. It’s a terrific, muscular, frenetic, sweaty rock and roll album, organ player and singer Jeff Conolly and company—J.J. Rassler and Peter Greenberg on guitars, Paul Murphy on drums, Rick Coraccio on bass—tearing through a set of originals and covers in front a sparse but game crowd. DMZ pawed through their collective album collection—covering the Stooges (“Raw Power”), the Sonics (“Cinderella,” “He’s Waiting”), 13th Floor Elevators (“You’re Gonna Miss Me”), the Troggs (“From Home”), the Fugs (“Frenzy”), among others— while Conolly’s own songs are blistering takes on his rock and roll heroes.

My favorite is a cover of the Kinks’ “Come On Now.” Here’s Ray Davies’s original, released by the Kinks as the b-side of “Tired Of Waiting For You” in January 1965:

And DMZ’s rampage a dozen, noisy years later:

DMZ’s arrangement is everything that was exciting and surprising about late Seventies rock & roll. Listen to that thundering rhythm section, the hoarse, urgent lead and gang-hollered backing vocals, the dual-guitar slashing—a snaking lead figure atop chunky power chords—, a hulking and vibrating music machine. The guitar solo’s borderline metallic. All of it filtering ‘60s Beat Music via Detroit through Boston’s grimy punk ethos. The Kinks’ recording is very cool, modishly well-tailored and sprightly. DMZ adds something quasi-menacing to Davies’s sly invitation: muscle, urban attitude, and the sonic near-chaos, sneer, and wattage that late-Seventies punk demanded. Slowed down, the song lurches rather than sprints, suggesting that Conolly’s got a different party in mind to head to. It’s great stuff.

Oh and the album’s back jacket features one of my favorite rock and roll images: Conolly on stage with one hand gripping a tambourine and the other wrapped in bulky bandages. Fear not: judging by his onstage requests for screwdrivers and beers, I'm guessing that Conolly wasn’t feeling much pain on that long ago summer night.

Meanwhile, out west….

By the time the Fluid had gotten around to their marauding take on the Troggs’ “Our Love Will Still Be There,” they’d been making loud noises for close to a decade. They formed in the mid 1980s in Denver, Colorado from the flickering embers of two bands, White Trash and the Frantix, with John Robinson on lead vocals, James Clower and Rick Kulwicki on guitars, Matt Bischoff on bass, and Garrett Shavlik on drums. The Fluid released their full-length debut Punch N Judy in 1986, before signing with SubPop in 1988. In the following heady years the band issued a handful of singles, two albums, Clear Black Paper (1988) and Roadmouth (1989), and an EP, Glue (1990). In 1993, hopeful to ride the cresting Grunge wave, the band signed with Hollywood Records, founded by Michael Eisner at The Walt Disney Company, and released Purplemetalflakemusic. Alas, the pixie dust settled but it didn’t stick; their major label effort stiffed commercially, and the band broke up soon after its release. (Do check out and turn up Purplemetalflakemusic’s righteous “My Kind,” however. Since the late ‘00s the Fluid have thrown the on-again, off-again reunion show. Rick Kulwicki died in 2011.)

When asked early in the band’s career about his band’s influences, Robinson sensibly replied, “I listened primarily to The Stones, Iggy Pop and Alice Cooper.” Five years later, on the cusp of signing with Hollywood, Robinson was asked again about his band’s musical sources, and this time threw a bit of a curve ball. “There’s no current rock music that’s influenced us, really,” he remarked, before adding, “Since Punch N’ Judy we’ve all gotten into big band a lot. We listen to a lot of big band and swing music. I can pretty safely say that’s been an influence because they really wrote songs. They’re short, they’re structured, they have really catchy melodies and those are givens for any big band song.” He added, “It’s not like we try to take pieces of those songs and put them in a block form or anything, but I think somewhere in there all those melodies make us be more melodic ourselves.”

The Fluid sure did swing on occasion—dig the chorus in the aforementioned “My Kind” or the half-time chorus in Glue’s killer “Black Glove”—but they primarily drove straight through whatever they were playing, at yowling, ear-bleeding levels. Yet I love Robinson’s acknowledgement of the sweeping if hard to detect pull of Big Band on the group; many of the Fluid’s like-spirited contemporaries were devoted to song craft, too, but the decibel levels often obscured the songs’ formalism. Butch Vig to the rescue!

In tackling the Troggs’ “Our Love Will Still Be There,” released in the U.K. in 1966 on the Troggs’ debut album From Nowhere, the Fluid paid their respects to a very particular kind of songwriter. The one and only Reg Presley’s pop-flavored yearnings were usually in service of brutally simple arrangements, creating songs that were as minimal as Top 40 pop got in their era. Yet next to, say, the bare-bones vibes of the band’s “I Just Sing” and “I Can’t Control Myself,” or the late, outrageously great “Feels Like a Woman,” “Our Love Will Still Be There” sounds positively Baroque. Presley declares his undying love that will outlast crumbling mountains, dry oceans, and war-torn nations. Bassist Pete Staples and drummer Ronnie Bond lay down the dry, Paleolithic bedrock, guitarist Chris Britton adds an elemental fuzz line, and on top of it all a stately Presley declaims, his tone a blend of shyness and resolve. The effect is lovely, and moving, and with the song’s stripped-to-the-bone arrangement, timeless indeed.

The Fluid’s version gives the impression of leaping onto the back of the Troggs’ song, all laughter, noise, and noogies. Loose-limbed and loud, the song’s taken at a swifter clip than the Troggs’—it’s 40 bpm faster—and fairly leaps out of the gate, Clower and Kulwicki’s guitars, razor sharp, slashing and chopping, sounding dangerous. Shavlik’s excitable drumming is the true center of “Our Love Will Still Be There,” the tom-tom and high-hat work and rolling fills translating the giddiness and rapid pulse rate of Robinson’s promises. (Want to imagine that an amped-up Who circa 1967 or ‘68 roared through a cover of the Troggs song? Close your eyes and pretend.) The Troggs’ original is affecting, yet sounds almost passive next to the Fluid’s exaltant, fiery take. Both songs persuade. I think that the Fluid got the girl.

Titus Turner’s “All Around the World” tells the tale of a man who, like the singer in “Our Love Will Still Be There,” will stop at nothing to display his love and devotion. Issued on Wing Records, a subsidiary of Mercury, in 1955, Turner’s tune was swiftly grabbed by fellow Southerner Little Willie John for his debut single, issued the same year, on King Records. Happily for Turner, Little Willie scored a hit with it.

Talk about swing! Turner and his band roll through the mid-paced tune yet drolly, soundtracking the singer’s boasts and promises: he’ll dig a ditch with a toothpick; he’ll fight off menacing lions with a switch; hell, he’d rather be a fly if that would allow him to just stick on her. He’ll give up all of his good time gals and settle for nothing less than happiness. It’s all fun stuff, merrily sealed with a kiss and a killer chorus:

‘Cause you know I love you, baby

Yes, you know I love you, baby

Well, if I don’t love you, baby

Grits ain’t groceries, eggs ain’t poultry, and Mona Lisa was a man

For the next fifteen years, “All Around the World” would be cheerfully tossed around from musician to musician, fan to fan, as “Grits Ain’t Groceries,” so funny and indelible was that chorus. In 1969, Little Milton released a version with that title, hitting number 5 on the Billboard R&B chart and 73 on the Hot 100.

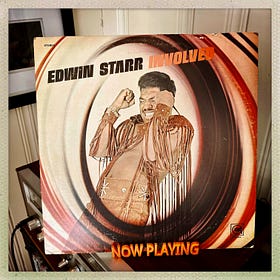

A year later, Edwin Starr, riding high on the commercial success of this ferocious “War,” a number one hit in the roiling summer of ‘70, released his fourth album War & Peace, “War” the album’s intimidating lead-off batter. (Starr’s third album, 1969’s Just We Two, was a collab with Sondra “Blinky” Williams, who’d later became famous for co-singing the theme to Good Times.) In its album review, Billboard described “Screamin’” Starr as a “powerful soul driver whose raucous rousing outbursts…bullies” his songs, rightly lauding War & Peace as a “power-house performance by Motown’s mightiest strongman of soul.” War & Peace also includes, with a wink, an outrageously fun cover of “All Around the World.”

The upbeat songs on War & Peace, with their four-on-the-four grooves and factory-precise yet muscular and rolling rhythms, feel of a piece with the sound cooked up by Motown’s session players the Funk Brothers. But “All Around the World” nearly bursts the seams of the album, rocking with such funkiness that I find myself remembering that the Detroit band Black Merda backed Starr early in his career as the Soul Agents, and played on several of his records, including “25 Miles” and “War.” Did the Soul Agents play on War & Peace? It’s impossible to know, given Motown’s notorious closed-door personnel policy. But it’s a fun what if? to marinate in for a while. The musicians who do play on War & Peace remain frustratingly anonymous, and I don’t know that my ear is trained well enough to determine with confidence that I’m hearing this or that Funk Brother guitarist, bass player, or drummer. I can make some educated guesses given the era in which War & Peace was issued, but I’d sure love to give precise credit. (We need more work like this by Brian Wright, who gives it the ‘ol college try.)

In the event, the musicians on “All Around the World” are having tremendous fun, and so is Starr, who kicks off things with a delirious “whah hoo!!”, tumbling into the song atop a snare-and-tom fill. The drummer’s grooving to some New Orleans shuffle only he hears, and the percussion, guitarist, and bass player are in funky syncopation that virtually requires whoever’s listening to get up and move. A gleeful moog keyboard solo replaces the original’s honking sax, tagging the recording with a time- and date-stamp, but Starr’s impressible singing—fun, funny, drunk on its own joy—elevates it all. If Garrett Shavlik’s drumming takes the star turn in “Our Love Will Still Be There,” then the rhythm guitarist in “All Around the World,” left channel, takes his bow here, shuffling between two chords in the verses, the song’s engine. If Wilko Johnson didn’t play this song on repeat, imprinting the guitar’s chugging rhythms into his own DNA, and come staggering into an early Dr. Feelgood rehearsal on Canvey Island clutching this album in his hands…well, grits ain’t groceries.

See also:

These are a few of my favorite B-sides

What follows is decidedly not a Holiday-themed No Such Thing As Was post. I’ll continue to half-seriously bah humbug that trend, yet I sure was happy to accept an invite from my pal and one of favorite writers Dan Epstein to his swingin’ Jagged Time Lapse

It's all right every time

Music’s like the weather. Some days you don’t notice it. Overplayed songs feel like that. You don’t pay attention to them anymore, or the songs don’t seize you the way they once did.

How much time will it take

I was hurrying, having realized nearly too late that I had to dash to the opposite side of town to grab something before lunch and afternoon classes. Irritated, I hopped into my car and, in too much of a rush to select a playlist on my phone, pressed Shuffle: always a gamble. How many times have I impatiently cycled through tens of thousands of songs, p…

DMZ killing it!

Great cover, it respects the original, but takes it to a completely different place.

The Kinks version is brilliant, too. If they didn’t have so many other great songs, that would be better remembered. The chorus has the secret sauce, the great Dave Davies, but also, the under-appreciated Raisa Davies, Ray’s wife at the time, who could be relied upon to hit the high notes.

The problem for me with the Fluid was that I heard their Troggs cover before I heard anything else they did — and it was just so perfect that none of their own stuff ever came close to touching it.