Beep-beep'm-beep-beep, yeah

Hop in with me as I listen to the entire Beatles canon on a road trip

Writing about the Beatles anymore—that is, for the last few decades—feels a bit like enthusing to someone about, say, a gorgeous sunset. Everybody’s seen one, in just about every medium, and no one “needs” to see another, let alone have one breathlessly described to them. Yet the transcendent, nameless joy and awe that a sunset might spark can feel as fresh and renewable as a surprising cool breeze—which everyone in history as also felt, and yet which can feel like a gift that, unbidden and casually generous, can change your mood for the rest of the day. Beatles music is like the weather I walk through, what I could take for granted. Pay attention, though, and I can still be blown away by both the simplest and the vastest of things.

A couple of weeks ago I drove solo from DeKalb to Detroit to catch an Amyl and the Sniffers show at the Majestic Theatre. For the trip, I decided to listen to my Beatles playlist from beginning to end, something I hadn’t done in a long, long while. The playlist includes the full run of Beatles singles (A- and B-sides), EPs, and albums in their U.K. releases order and song sequencing. I’ve added some bonus cuts too, for a fuller sonic picture:

A handful of tracks the Beatles recorded before their first single, “Love Me Do” in October 1962: “Cry For a Shadow,” a Lennon-Harrison (!) instrumental, and “Ain’t She Sweet,” recorded in Germany in June 1961; “Hello Little Girl” a Lennon-McCartney original from their 1961 Decca auction, and Mitch Murray’s “How Do You Do It,” cut during the “Love Me Do” sessions. I wanted something from the historic Decca audition, and Lennon’s innocent “Hello Little Girl” is my favorite of the bunch. I include “How Do You Do It” because I’ve always like the song, and because the cheeky Beatles allegedly cut a deliberately half-hearted version so that George Martin might pay more attention to their originals. (As with most Beatles stories, separating fact from lore is a fool’s errand.)

“One After 909,” recorded during the March 1963 sessions for “From Me to You” and left in the can. I dig this version a bit more than the “rooftop” performance from six years later for its rough edges and boyish energy. (Though Harrison’s lead is rightfully scorned by Lennon. “What kinda solo was that?”)

Four tracks from the band’s BBC radio sessions: an original, “I’ll Be On My Way,” and three killer covers, “Some Other Guy,” “Soldier Of Love,” and “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Cry (Over You).” The original’s elementary, for sure, but the lads were breathing catchy melodies, and the song would’ve slotted in nicely on Beatles For Sale when they were casting about for material. “Some Other Guy” is sublime, the track I play for anyone who’s skeptical of the Beatles’ ability to rock hard (imagine them produced by Shel Talmy) and one of my favorite Lennon vocals. “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down” shows how effortlessly and originally the band could rearrange another’s song to suit their style—I can picture Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison onstage gang singing “…what I’m gonna do! Iiiiff you…” at the end of the bridge, shaking their mops of hair and making everything about the song instantly their own. (Down the years, other tracks from the BBC sessions have slipped in and out of my playlist, including “Sure To Fall (In Love with You),” “Clarabella,” “Crying, Waiting, Hoping,” and “Lonesome Tears in my Eyes.”)

“Shout,” the boisterously happy Isley Brothers’ cover they recorded in April 1964 for the Around the Beatles television program

Two outtakes, “Leave My Kitten Alone” cut during the August 1964 Beatles For Sale sessions, and “That Means A Lot” from the February 1965 Help! sessions. The band’s performance and Lennon’s vocal in particular on “Leave My Kitten Alone” smoke. (I was blown away when I first heard it on a bootleg back in the late 1980s, and I’m still among those who feel it would’ve served Beatles for Sale better than the bizarrely hokey “Mr. Moonlight.”)

Three tracks from the May 1968 “Kinfauns” demo recordings session at Harrison’s bungalow, Harrison’s “Sour Milk Sea” and “Circles,” and Lennon’s “Child of Nature.” “Circles” is wonderful—peak-era Harrison the Philosophical One—and I would’ve loved to have heard what his band might’ve done with the tune, and with…

Harrison’s demo for “All Things Must Pass” that he recorded alone at EMI in February 1969. (On my playlist this slots between the “Get Back” and “The Ballad of John and Yoko” singles.)

McCartney’s demo for “Come and Get It,” recorded solo in July 1969 during the protracted Abbey Road sessions

Though the Yellow Submarine soundtrack album was released in January 1969, “Only a Northern Song,” “All Together Now,” and “It’s All Too Much” were recorded in 1967, and “Hey Bulldog” in early 1968; because no additional work was done on them, they’re slotted between the Magical Mystery Tour EP and the “Lady Madonna” single. I use the version of “Across the Universe” that appeared on the No One’s Gonna Change Our World benefit compilation released in December 1969, rather then Phil Spector’s treacly version from Let it Be.

I end the 232-song playlist with “Free as a Bird,” “Real Love,” and “Now and Then,” Threatles bashers be damned. (Hey, I’m a completist, and I truly like “Real Love.”)

Listening to the Beatles career from start to finish is nothing less than a crash course in cultural history, with the lesson-plan on fast-forward. Any class that begins with Kennedy and ends with Nixon will be engrossing; a class that moves from “Love Me Do” to “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide except for Me and my Monkey” is gonna be a blast.

In truth, the experience this time around was even more edifying, not to mention more thrilling, than I’d guessed. Listening from single to single and album to album in succession graphically illustrated the band’s potency (to use Pete Townshend’s descriptor of praise) and work ethic (native to the lads, and required by industry demands) and the preternatural ease with which they evolved under enormous pressures. Listening while driving for over 300 miles only underscored that progress: I felt as if I were hurtling forward in time along with the band as they moved from Mersey Beat harmonics to Americana roots to weed-laden inwardness to acid-drenched mind-journeys to the inevitable, bittersweet end of the English fairy tale, their hair lengthening, their clothes brightening as I listened.

Twenty or so minutes into the drive “I Saw Her Standing There” came on. At McCartney’s brash count-off I was already looking forward to my favorite moment in the song—in any Beatles song, really—the final bar of the second bridge, when McCartney, having just harmonized with Lennon on the ecstatic “I held her hand in myyy-yeeen” line, sings “Oh, we danced” as Lennon barks out a wow! and Starr, excited, hits a triplet on his snare. It’s passing of a baton among band members that lasts maybe two seconds—to me it’s everything, among the first moments in a Beatles song that I fell in love with as a kid, knocked out by the locked-in fun and joy of it all, a random blip in time in a recording studio that captures an early, hungry, joyful, rock and roll loving band poised for who knows what. And the moment shifted into a new, higher gear for the road trip. Coming soon: “Twist and Shout,” “She Loves You,” “It Won’t Be Long,” “You Can’t Do That,” and the rest.

As I grooved along I-90, the cumulative effect was as if I’d been cast under a spell, or were inside of a delightful, amiable magic trick. Maybe it was a contact high of sorts: the car seemed to elevate from the road as Rubber Soul and Revolver played; I blinked away bright, colorful shapes; the sun always seemed to be out. I sang along to every song. The drive took about five hours, so I knew in advance that I’d be listening to the playlist in two parts. The hinge at where I paused couldn’t have been more appropriate. I cruised down Cass Avenue in Detroit a few blocks from my hotel as “She Said, She Said” from Revolver was playing—precisely halfway through one of the band’s most adventurous albums, one that looked backward and forward. I pulled into the parking lot as the song faded.

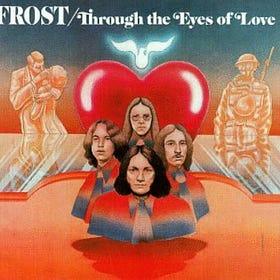

In the back of my mind during the trip, on an alternate track, a song played by a different band. I’ve been preoccupied with the Frost’s “Fifteen Hundred Miles (Through the Eye of a Beatle)” for a few years now, digging the of-the-era vibe of freaky playfulness and Rock Mythologizing, one band beholden to the magic of another. I wrote about the tune here:

Through the eye of a Beatle

Buckle up, the Frost sang, we’ve got a long ride.

As a rule, I don’t sleep well on the road. After the show, I tossed and turned for a few hours and stared grimly at the ceiling that slowly brightened with the dawn. I eventually “woke up,” mainlined some coffee, grabbed my Third Man Records bag (at Jack White’s joint earlier in the day I’d snagged a couple of Redd Kross albums I didn’t have, the Neighb’rhood Childr’n debut, two Margo Price 45s), and—after paying my respects to the Ghost of the Grande—hit the road. What was waiting for me as I pulled out of town? “Good Day Sunshine.” Indeed.

As I was driving on very little sleep after a night of loud punk/pub rock noise, and because I was entering the 1967 portion of my Beatles Trip, the experience driving east was, shall we say, multicoloured. The transition from “Tomorrow Never Knows” to “Strawberry Fields Forever” to “Penny Lane” to Sgt. Pepper’s took the top of my head off, a dazzling run of visionary, mold-breaking, horizon-setting pop art, and I felt as if I were always a second or two behind each song, beholding them anew.

Yet as I drove across lower Michigan while the band drove through their post-Pepper daze, the songs lost a bit of traction. (For every “I Am the Walrus” there’s an “All Too Much,” for every “Fool in the Hill” a “Blue Jay Way.” Sorry, George.) Filler became more glaringly apparent, especially in such a condensed listening session as I was enjoying. By the time the “White Album” arrived, I felt as if I was listening to a band going uphill. Ian MacDonald in Revolution in the Head: “Shadows lengthen over [the “White Album”] as it progresses: the slow afternoon of The Beatles’ career.” (Though listening to “Revolution No. 9” while hurtling though space at 75 mph is, it must be said, a trip.)

None of this is news, of course, and is certainly informed by what we’ve all read and heard since the 1970s about fractious studio sessions, shifting alliances, solo songs recorded with half-attentive bandmates, cooling friendships, “boys turning into men,” et cetera. As I listened to the brilliant ensemble playing on “Come Together,” “Hey Jude,” and “Don’t Let Me Down” for the thousandth time, I wished for the thousandth time that the guys could’ve somehow kept it together for another album or two. The balm against such childish longing was my marveling at how their songwriting developed and matured over that startlingly brief eight-year recording career: “There’s a Place” to “Happiness is a Warm Gun.” “All My Loving” to “Penny Lane.” “Don’t Bother Me” to “Long, Long, Long.” To move across, to hear and feel and be sent by such vast, tuneful, emotionally-driven, intellectually-curious music—a journey to the far out and back in only ten hours—is to be reminded of how remarkably dynamic and still-refreshing that music was, and is.

As I approached home, the playlist wrapped up with the three post-breakup recordings; arriving only minutes in playlist-time after the scattered highs on Abbey Road and Let it Be, the newer material felt especially contrived and trifling. Alas. A bit earlier I’d been snagged in a typical and typically fraught traffic jam along the grim I-94/-294 corridor, at one point literally surrounded by a towering gang of exhaust-spewing semi-trailer trucks. At least I had “Let it Be” for comfort.

See also:

Gotta hear it again today

All their little plans and schemes

“The Beatles cartoon was great” by anonymouse-creations via DeviantArt

”The Beatles 1969” by deej240z via DeviantArt

Joe, I'm going to quote this in the essay I'm preparing about the Beatles:" Listening to the Beatles career from start to finish is nothing less than a crash course in cultural history, with the lesson-plan on fast-forward. Any class that begins with Kennedy and ends with Nixon will be engrossing;..." This is SOOOO true and can't be said too many times. Thanks for sharing your wonderful listening. There's something for everyone in Beatles songs, many to choose from. What is also significant about the Beatles is that their careers predated Kennedy because of their admiration for good old R 'n R, and the influence they had on bands after the breakup is still ongoing. Their history will never stop.

Awesome road trip diary! It reminds me of the days of the legendary "Beatle-Pod," which I created for my kids when they were little and only wanted to hear The Beatles. I took my old (too small) iPod and filled it up with only Beatles music, assembling one master playlist in chronological order just as you did, with a very similar selection of extras. The icing on the cake was having my friend digitize the counterfeit copy of The Beatles Christmas Album I had picked up when I was in high school. This allowed me to insert the appropriate Christmas fan club single to delineate the changing of the years. My wife suffered a little because she didn't (and still doesn't) "get" their British humor, but the kids loved it all!