Can I borrow some?

In his demos, Billie Joe Armstrong moves from personal to private and back again

Demo recordings often feel and sound like back-of-the-book footnotes or discarded film on the editing room floor. And though they're sometimes revealing, I usually don't find them very fun to listen to. Many fans like demos, as the recordings allow a glimpse into an intimate process begun as a private experience, some "I'm in the room with 'em!" action. They can range from slivers of song to fully-realized constructions. Pete Townshend, whose backlog of home demo recordings nearly rivaled in size the Who's officially released cannon, often produced demos so complete that all his band had to do was show up.

But occasionally demos can storyboard the artistic process. In the early 1990s I bought a Beatles bootleg that gathered all of the available fragments of John Lennon's home demo tapes for "Strawberry Fields Forever." His early, fumbling scraps on acoustic guitar with hesitant vocals gave the impression of a pre-song in a dark tunnel. "Piecing the song together...[Lennon] seems to have lost and rediscovered his artistic voice," Ian MacDonald wrote in Revolution in the Head, "passing through an interim phase of creative inarticulacy reflected in the halting, childlike quality of his lyric...moving uncertainly through thoughts and tones like a momentarily blinded man feeling for something familiar." I listened obsessively, and afterward played the Beatles' final, released version, the band's two studio recordings stitched together, staring out the window of our fourteen-sided home in the outskirts of Athens, Ohio as the song coalesced over a long afternoon. Contact high, indeed.

Billie Joe Armstrong is a classicist songwriter. He's tied to tradition even as his and his band's approach is, or was, to buck tradition in gnarly punk rock fashion. Green Day roared up the charts and into arenas with short-fast, often angry songs, but the tunes were usually pretty traditional (though not temperamentally or politically conservative)—rock and roll disguised as punk. Check Armstrong's record collection: there's as much mid-60s AM radio and late-70s power pop as there are Replacements and Hüsker Dü, to name only two of his chief influences who were also loud pop bands at heart. His favorite musician? Joey Ramone, who worshipped the Who and the Ronettes equally. Armstrong's pop-punk songs never stray into the avant-garde, and so there are bound to be fewer discoveries unearthed in his demos than in those of other artists more inclined toward shoot-in-the-dark experimentation. I'm sure that Armstrong often surprises himself as he composes his songs, but as a formalist his revelations arrive in a controlled environment.

The new Nimrod boxset is a blast, containing the original album, some demos, including takes on Elvis Costello's "Allison" and the Ramones' "Texas Chainsaw Massacre," and a stomping, warts-and-all live set recorded at The Electric Factory in '97. The sprawling Nimrod was, as it turns out, a fairly experimental album for Green Day, as they stretched out a bit genre-wise. There's some folk, some ska punk, some surf, the string-laden ballad "Good Riddance (Time Of Your Life)." "This is a record we've been thinking about for the past six years," Armstrong reamarked at the time of the album's release, adding, "The record's about vulnerability in a lot of ways—throwing yourself out there."

Among the demos, I was immediately drawn to "Black Eyeliner." Recorded solo by Armstrong on electric guitar with a bit of reverb and an overdubbed, scratchily yearning EBow, the song mines sexual territory, gender-blending cut with desperation. A boy asks a girl if he can borrow her eyeliner, "To make my eyes look just like yours." He hopes the gesture will be reciprocal, so that later, if she'll deign to kiss him again,

Can I apply your black eyeliner one more time

to make your eyes look just like mine?

He's half asleep and half awake ("sleepwalking eyes open wide") and—and where are they? Her bedroom? A bathroom at a club? A street?—hopeful, I guess, that if she says yes he'll awaken to something fuller. The phrase "bloodshot deadbeat" hovers in the air above the two of them, but we don't know who it describes. Yet mascara's running down her face, "leaving traces of mistakes." Again: her mistakes, or his? Either way, the vagueness feels emotionally true to me, those hoped-for moments between a couple, exhausted pleas at midnight, defenses down. Armstrong's performance of all of this is aggressively unguarded, his voice catching the pitch of vulnerability and fear even as he strums like mad. I like the song a lot. It ended up on the floor.

Three years later, there it is again. Now the desperation's inside of something quite different. I wrote about "Church On Sunday," from Green Day's Warning album, a decade ago, and the song still matters. A plea for compromise from the singer to his partner, long assumed to be Armstrong and his wife Adrienne Nesser, the song imports the bleeding mascara, sleeplessness, and mistakes from "Black Eyeliner," but, more mature now, it names things, too. The mistakes belong to the singer, who's probably also the deadbeat: her makeup's running now because of him. The problem? He's a liar from whom the word trust is a profanity, though he swears to tell the truth to her from now on. He'll earn her respect, too, if she can muster some faith in him, and he'll do that by promising to go to church with her and their family—if she'll go out with him on Friday night.

All compromises are two-headed beasts. This one's a battle between weekend excesses and Sunday redemptions. Sounds like life to me. "Church On Sunday" is one of Green Day's unheralded pre-American Idiot songs. Mike Dirnt and Tré Cool play their parts, grinningly amping up the urgency, and the overall feeling is exalted. Armstrong trusted his songwriting instincts in resurrecting and then deconstructing "Black Eyeliner," fashioning part of its lyric as a pre-chorus in "Church On Sunday." (Perhaps in the back of his mind he heard Ray Davies: "If after two weeks you still can’t write your middle-eight, the best course of action is to see a psychiatrist." In the event, Armstrong would use "Black Eyeliner"'s changes and melody eighteen years later in "Kill Your Friends," a tune for his side band the Longshot. It seems that he couldn't shake the song.) What's fascinating is how the intimacies shift between the demo and "Church On Sunday." It's fun to imagine that the kids in "Black Eyeliner" are the grown-ups in "Church On Sunday." They were really just playing makeup the first time around. Things felt compelling and intense, sure, but no one was around to tell them just how intense things would get in the future: marriage, family, lies, trusts broken, healing forged.

Here's Pete Townshend, one of Armstrong's heroes, in a recent interview in Guitar Tricks Insider: "I don't feel the need to celebrate adolescence anymore. I'm starting to get bored with writing about it. It's starting to become a semi-middle aged attitude." He continued,

I don't feel at all ill at ease with where I am. I don't feel I'm suffering from maturity. I'm quoting myself there. I said that in an interview with Melody Maker—the best thing I ever said—that somebody suffers from maturity. A lot of people walk around acting like adults. It's got nothing to do with morality or dignity. I mean you can be free or you can act stupidly, but you can still be dignified. Sometimes you can still be within the law.

Armstrong gets it. In "Black Eyeliner," the singer wants to get closer emotionally to his partner by looking the same as her, two like-spirited outsiders clasping hands and snarling at the world in their DIY makeup. In "Church On Sunday," all he sees is just how impossibly far he is from her now. All grown up.

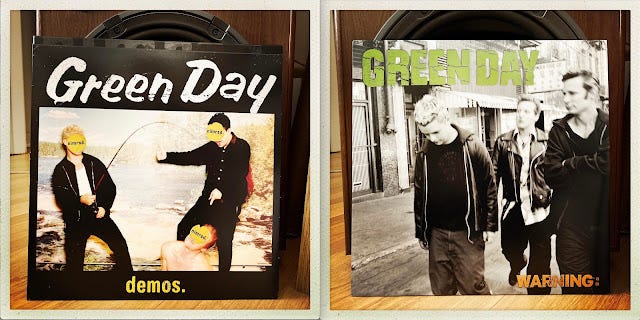

Illustration of Billie Joe Armstrong by Logan Hicks