Can you feel it coming?

A valuable, late-arriving lesson courtesy Phil Collins and Hugh Padgham

During the first week on my Writing Arts Criticism class, the students and I listen to a traditional version of “The Star Spangled Banner,” giving the ‘ol college try of attempting to hear with fresh ears a song that’s familiar and unsurprising, like the weather, or our own bodies, something that we end up taking for granted. Then we listen to several very different covers of the song: an acoustic performance by Victory Boyd; Jim Hendrix scorching the earth at Woodstock; and an arrangement in which the full song is transposed to a minor key. We listened to version each twice.

Before we watched Boyd’s performance for the second time, I provided some context: Boyd had posted her version to YouTube in September 2021 after she’d been “cancelled” (her word) by the NFL. She’d been scheduled, though no contract had been signed, to sing the National Anthem at an opening week game; after she’d disclosed to league officials that she’d refused a COVID vaccine shot claiming a religious exemption, the league dropped her appearance. Unbowed, she uploaded her version “not for the theatrics of a football game,” she remarked, but because “this time I sang for America. To remind her who she is… the land of the free and the home of the brave.” She added, “This is dedicated to anyone that has taken a stand for freedom. I stand with you.”

After my students learned this, the temperature in the room changed a bit, as they felt compelled to reassess the hoary promises embedded in that old anthem, this time sung by an Black woman asking her listeners to consider what the words mean even if they may disagree with her stance. Many of my students did/do disagree with Boyd’s choice, and they often shift in their opinion of the performance after learning this information.

Hendrix, unsurprisingly, sets the room alight. The first time we listened I blanked the screen; the second time we watched Hendrix performing. Most of my students know who Hendrix was, know his name as uttered reverently by their parents, uncles, and aunts, but surprisingly few had seen the footage. I myself hadn’t in years, and was nearly moved to tears watching a lone Black man destroy and reconstruct the national anthem at 8:30 in the morning, his playing hanging loosely from the melody, toying with it, really, before devolving into those hair-raising sounds of screeching jet fighters, the sound of carpet bombing and the roar of disbelieving and angry resistance caught through a guitar and amplifiers on a farm in upstate New York. Hendrix’s intentions, of course, especially at this point in his musical evolution, weren’t punk, but the song as he deconstructs it was as pissed off and politically charged as anything the U.S. and U.K. punk bands would sneeringly deliver a decade later.

“Through feedback and sustain, he had taken one of the best-known tunes in America and made it his own,” wrote Charles R. Cross in his Hendrix biography Room Full of Mirrors. “For Jimi, it was a musical exercise, not a manifesto. If he had any intention of making a political statement…he didn’t speak of it to his bandmates, friends, or even later to reporters, who consequently hounded him with questions suggesting such a motivation. At a press conference three weeks later, he said of the song, ‘We’re all Americans... it was like ‘Go America!’ ... We play it it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see’.”

Though it’s overfamiliar, Hendrix’s performance never fails to startle me. And yet I hadn’t realized that I needed a reminder of just how thoroughly and thrillingly Hendrix blew up the music, turning it into something frightfully new, its terms now naked and graphic, the words “national” and “anthem,” and the ideas in them, turned on their heads. If critique wasn’t Hendrix’s intention, it was surely—after his mood, his gifts, his intuition, “the way the air is”—the result. Approaching the music from different angles, I asked my students to listen to whatever questions or arguments, or well-worn comforts and pieties, were in the air above them.

We also read Kelefa Sanneh’s essay “The Rap Against Rockism” which, though it ran in The New York Times in October 2004 on the cusp of the YouTube and streaming era, still has relevance for my students. One graph in particular hits home down the decades:

A rockist isn’t just someone who loves rock ‘n’ roll, who goes on and on about Bruce Springsteen, who champions ragged-voiced singer-songwriters no one has ever heard of. A rockist is someone who reduces rock ‘n’ roll to a caricature, then uses that caricature as a weapon. Rockism means idolizing the authentic old legend (or underground hero) while mocking the latest pop star; lionizing punk while barely tolerating disco; loving the live show and hating the music video; extolling the growling performer while hating the lip-syncher.

Though “rock ‘n’ roll” is even less culturally significant now than when Sanneh was writing, gatekeeping has only grown more rigid. My students volunteer one story after another in which their genuine though late adoption of a band offends some pious OG fans, or their love of country music alienates them from their punk friends, or, in the case of one frustrated student, his very youth apparently precluding him from “getting” a heavy metal band, the older fans virtually frowning down at him with contempt. Such gatekeeping isn’t new, yet has developed stridently in the age of Spotify, during which entrenched camps, exponentially sprouting in number, have grown only more entrenched.

I’m guilty myself of the most insidious kind of gatekeeping: internal. It’s one thing for some to mock others for their genuine pleasures—Weekend New Wavers, fans who ignore or have no knowledge of a band’s indie, DIY releases once that band’s made the leap to the majors, etc.—it’s quite another thing to deprive yourself of genuine pleasure. I wielded my anti-mainstream bias during my mid- and late-teen years as a weapon, a word Sanneh uses, slicing and dicing at the opposition. As the 1980s dawned, I still connected with many of the songs that starred the Top 100; the Police were my favorite band for several years, and mainstream popular music, as it does and always will, scored countless profound and trivial moments during the comic opera of puberty and beyond.

But by high school, I was establishing my frosty relationship to the mainstream, an enormous swath of popular culture that produced larger-than-life figures (Madonna, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, et al) adored by a sea of folk who dressed and wore their hair in ways that I didn’t want to. At age 16, 17, I was starting to tune in to an alternative universe I wished entry into—goodbye WPGC’s Top 40 rundown, hello WHFS’s progressive free-form playlists; goodbye Saturday Night Live, hello SCTV; goodbye the Police and Rolling Stones, hello the Jam and Replacements—a time-honored and familiar gesture to so many. Nervy Punk and snarling Garage Rock seduced me away from the comforting ideology of Top 100, and anyway I wanted to live in a world in which Hoodoo Gurus, XTC, and Marshall Crenshaw had million-selling singles, knocking Irene Cara, Kenny Rogers, and Hall and Oates down the Billboard charts. (But then Crenshaw would’ve gotten “too big” for me, but that’s another tired complaint. The Clash, R.E.M., and Nirvana’s successes produced their own complex fables.)

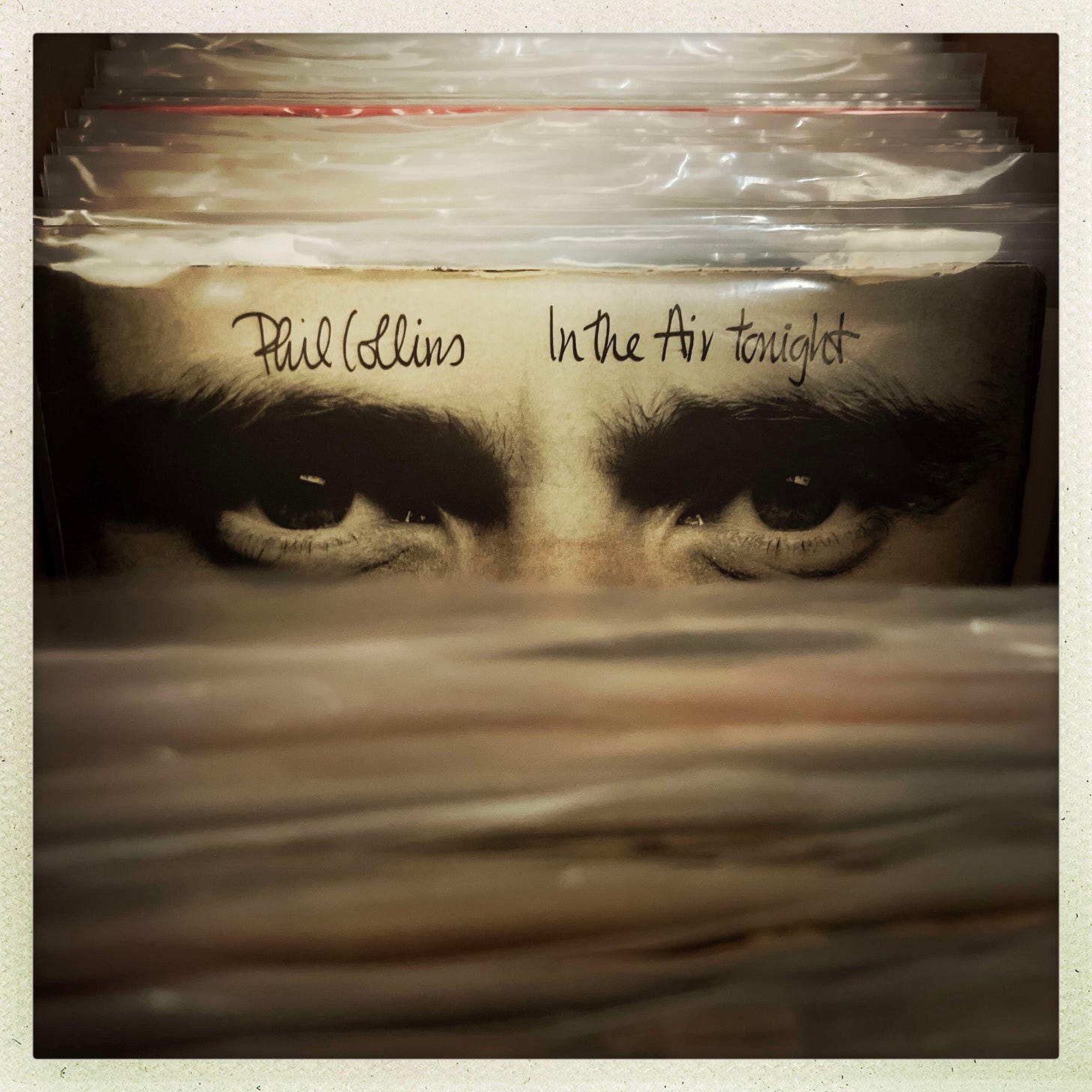

The other day, I came across a reference to the English producer and engineer Hugh Padgham and his work assisting Phil Collins on “In the Air Tonight,” Collins’s mega-hit from 1981. Padgham, of course, engineered many of XTC’s songs (including the sublime “Respectable Street” and “Senses Working Overtime”), but back in ‘81 in the library at Our Lady of Good Counsel I hadn’t yet caught up with Andy Partridge (he was around the corner). All I knew was my friends ecstatically air drumming to a song that I couldn’t stand. I was beginning to distrust gated reverb drums, frowning instinctively when producers created sounds that I couldn’t hear in the natural world, sounds that I associated with a mainstream ethos away from which I was slowly, imperceptibly drifting. A couple of years later, the song’s iconic appearance in the enormously successful Risky Business movie and soundtrack sealed “In the Air Tonight” as a theme song of sorts for a preppy/jock crowd against which I was rebelling, in my mild way. (Prince was on the soundtrack, yeah, but I hadn’t caught up with him yet, either.)

Of course, when “In the Air Tonight” was released in the first week in January 1981 there were plenty of songs on the radio that I dug: John Lennon’s “(Just Like) Starting Over,” which was firmly entrenched at number one, Lennon’s murder only a few weeks old; Blondie’s “The Tide Is High”; Springsteen’s “Hungry Heart” (with a drum sound that I did love); the Police’s “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da”; Kool & The Gang’s “Celebration”; Pat Benatar’s “Hit Me With Your Best Shot”; Queen’s “Another One Bites The Dust.” But there were many more singles with which I simply didn’t connect—those by Barbra Streisand and Barry Gibb, Air Supply, Eddie Rabbitt, Barry Manilow, the Doobie Brothers, REO Speedwagon, Michael Stanley Band, etc.—and Collins’s firmly lodged itself in with them.

Anyway, the moment I saw the title the other week, Collins’s song dutifully began playing in my head. The old resistance flared, and then dimmed, surprisingly. Perhaps because of the recent conversation I’d had with the students about gatekeeping and “guilty pleasures,” not to mention Amy’s enthusiasm for the song, I heard something else as “In the Air Tonight” played on my interior stereo. A few days later, I hunted down the 45 to give the song a proper listen. What I heard was what I wish I’d let myself hear four decades ago, a haunted, haunting classic that had I paid real attention to I would’ve recognized sounded like nothing else on the radio at the time. Though Collins has been clear about debunking various misreadings of the lyrics, he’s been vague about their origin, citing his messy divorce and the subsequent anger and resentment. He claims to have originated the bulk of the lyrics on the spot in the studio, spontaneously in touch with trouble and the need to express it.

The song’s a marvel, its unique and of-the-era sound in service to eternal complaints—“I’ve seen your face before, my friend / But I don’t know if you know who I am”; “I know the reason why you keep your silence up / No, you don’t fool me / Well, the hurt doesn’t show, but the pain still grows.” Those words could’ve been felt, thought, and uttered at any time in human history, yet the delivery system here (drum machine, synthesizer, vocoder) date-stamps them. “In the Air Tonight” still fits me a bit awkwardly, and I don’t know that I’ll comfortably grow into it. That iconic drum fill in the last verse still sounds showoff-y to my ears, new-toy industry that overpowers rather than heightens the foreboding mood. (And the track’s reverb feels like a sound effect.) Yet throughout, Collins’ vocal hits that timeless sweet spot between anger and regret. As the song fades you realize that though you’ve been bullied a bit by the modern machinery, the human voice is what lingers. The song’s sound, as opposed to its feeling, is cool to the touch, and I resisted that chill for many years. Now it sounds like nothing less than inside of the singer’s sorry head, and it’s cold in there. And I always heard the plaintive “Oh, Lord” in the chorus as “Hold on.” Same thing, really.

Listening, really listening, to “In the Air Tonight” now, I feel as if I’ve seen a remarkable mountain or a handsome building, something I’d driven past for years without noticing, for the first time. I’ve never considered how beautiful yet bittersweet the melody is, how the song might gain dimension if played acoustically. I hadn’t bothered. Given my age and biases, I don’t think I was quite ready to hear “In the Air Tonight” when it was released. So perhaps I’m being a little unfair to myself, and, indirectly, to you too, as you’ve certainly wrestled with your own cultural blind spots. A great song doesn’t matter when it’s heard, I guess, but how.

In the end, Eoin Sands’s minor key rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” might’ve moved the classroom even more then Hendrix’s sonic take-down. Sands’s arrangement, wittily titled “Sad Spangled Banner,” softened the charged mood in the room, as if things had abruptly moved from color to black-and-white, a trippy sunrise replaced by an unhappy dusk. After two minutes, we all felt that we’d had a crash course in an alternate history of the United States, where this funereal arrangement is how the anthem’s heard by many, its regrets and sorrowful disappointments as familiar to them as the rhymes in the lyrics. We know what a minor key transposition does, theoretically: such a trick can turn an innocent early-60s pop tune into something that sounds strange and wounded. There are a lot of minor key versions of the national anthem online. They seem to have struck a chord.

After we listened, I asked the students to get into small groups and discuss and rank the versions, by whatever aesthetic standards they wished. The conversations were terrific and lively, surprising and funny. Nothing really new here, yet by the end of class we had yet another reminder of what sound can do, and how form can graphically affect content, as if someone had switched off-and-on the lights in the room. And how our prejudices can alter a song. Coming at “In the Air Tonight” as I did, woefully late, at an angle, biases on mute, I learned yet another lesson, number 345,678, filed away in a growing folder.

See also:

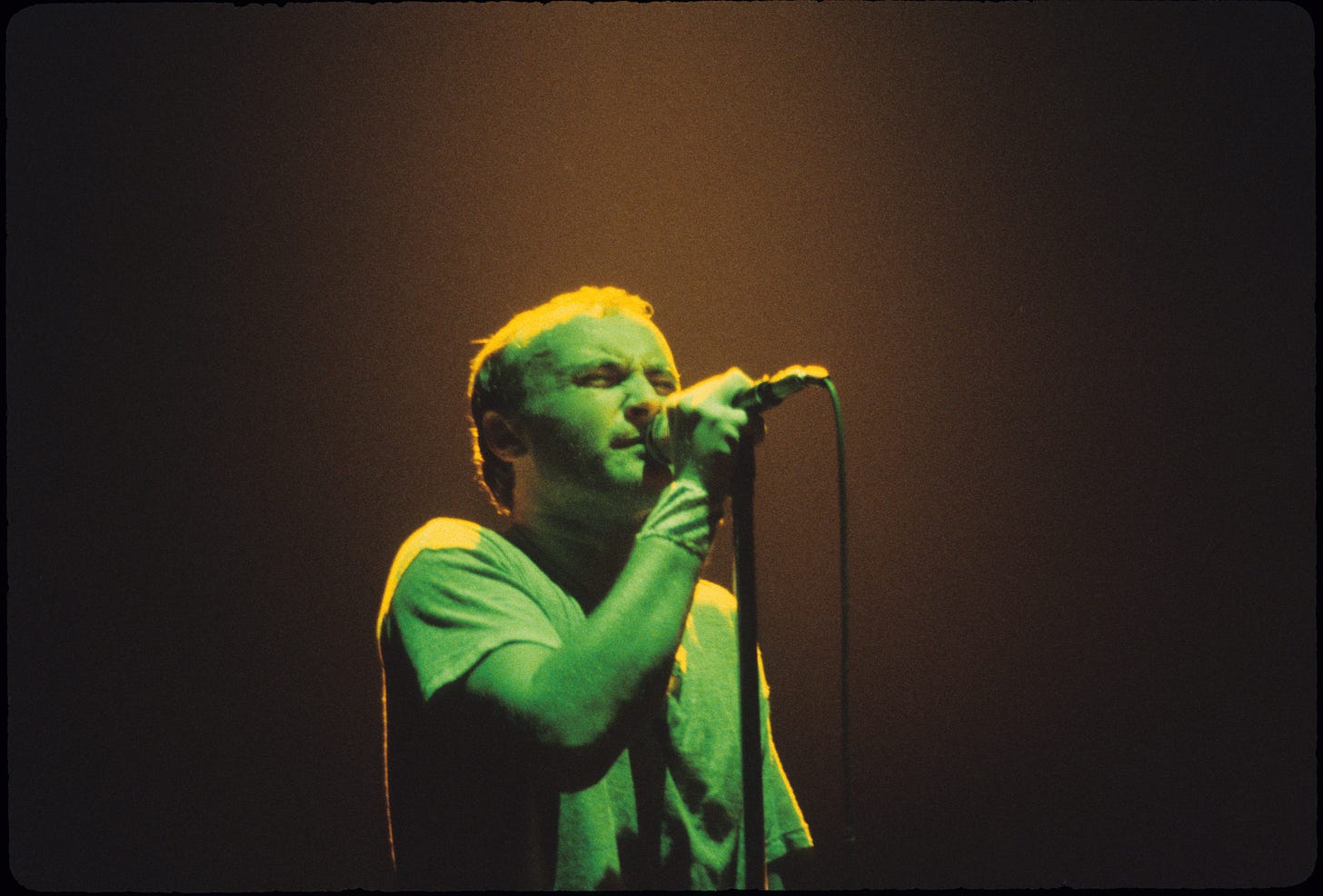

Photo of Phil Collins by Philippe Roos, Strasbourg, France, 1981-10-28, via Wikipedia Commons

What a great class, Joe! I would have loved this as a student. No wonder you get such great participation if you're teaching like this.

I've heard the Hendrix version many times but not the other two. Such different versions that tell very different stories about the country. Quite eye-opening.

Been there, done that myself in terms of being judgemental about artists and their music. But now that I'm reading and writing about them all the time for substack, I come across story after story of artists being forced by producers and labels to record their work against their own desires and intentions to make it commercial. If anyone survives in the music business and puts out a good song, kudos to them.

"In the Air Tonight" is an arresting tune, mysterious lyrics, sludgy pace, and a drum fill that I always listen for and wonder what it means!

Great article. To me there are no guilty pleasures you either like a song or you don't.