Castaways, Part 1

From each Green Day album, I choose the best song that wasn't issued as a single

Singles are funny, stubborn things. Introduced in 1949 by RCA Victor as a lighter and less-breakable substitute for the 78 rpm shellac disc, they soared in popularity in the 1960s and ‘70s, grew five inches wider in the ‘80s, were virtually extinct by the 2000’s (but for its eternally cool club-mix cousin, who’s always out late), suffered through poor pressings and the indignity of errors on labels, and have made an improbable comeback of sorts, riding the vinyl resurgence of the last decade or so. I fondly recall Jeremy Tepper’s 45-only Disel Records label from the ‘90s; it felt vaguely quaint even then, and would come to feel positively anachronistic in the CD era. Yet surprisingly, mp3s and streaming brought back the thrill (and the commercial potential) of a standalone single. And I can now regularly look forward to new seven-inch 45s from some of my favorite bands.

From the band and record labels’ perspective, of course, a single has long required that a choice be made—precisely, which song? Large is the lore of label heads making what turned out to be the wrong decision, ruing their instinct for printing cash when their choice for a single stiffed on the charts. Often, bands and labels clash over which song should be the lead single in advance of an album, or a support single if that album’s wobbling on the charts.

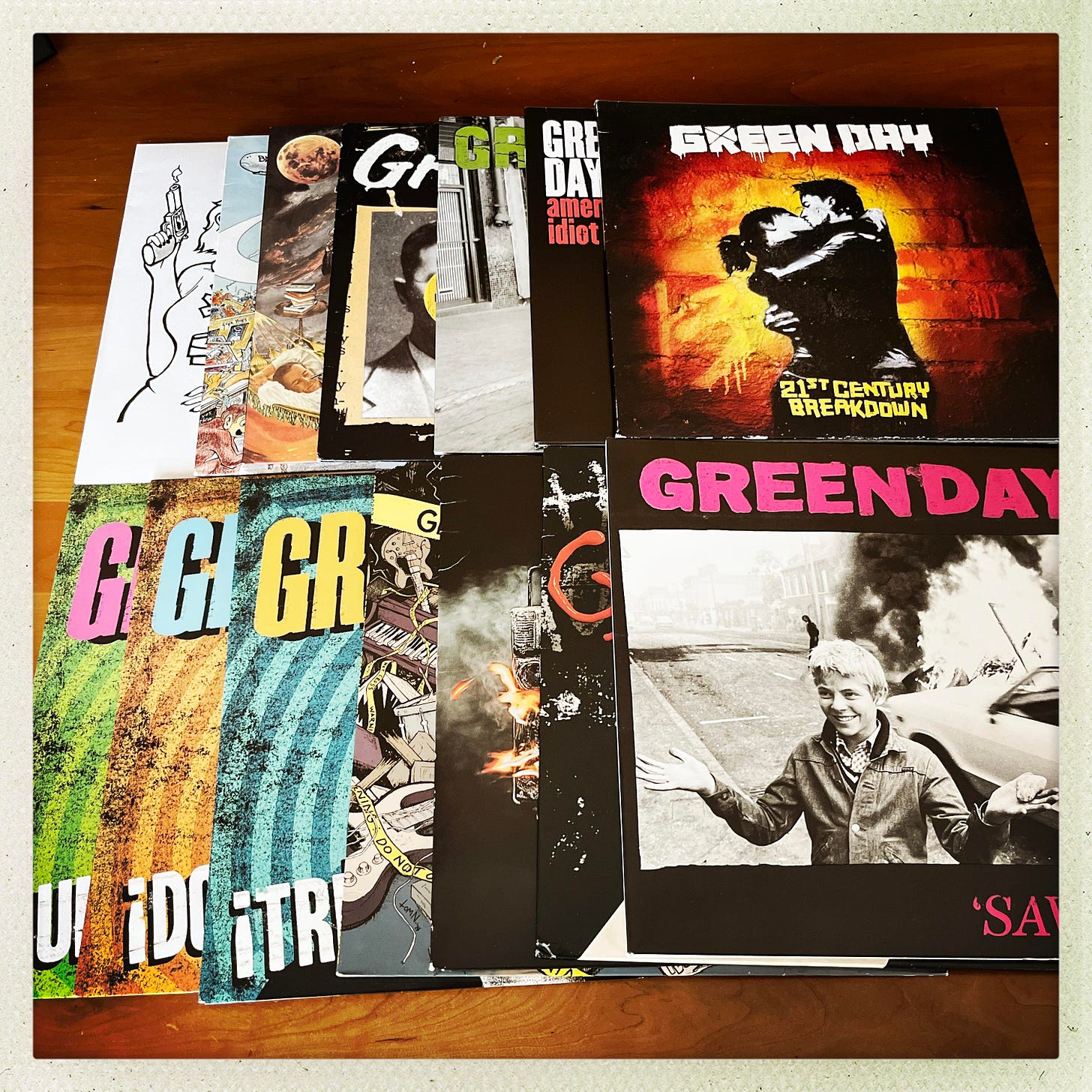

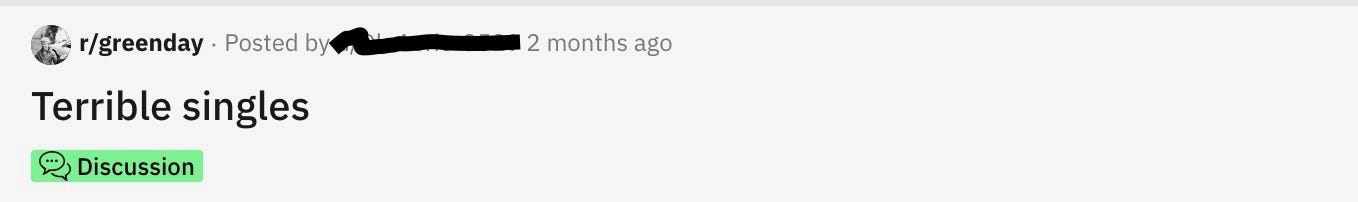

Fans certainly have their takes of varying temps. “Making mistakes is a lot better than not doing anything,” Billie Joe Armstrong once said, echoing at least half of the endless Reddit arguments over which Green Day songs should have or should not have been released as singles:

Etc.

Since 1994, their first year on a major label, Green Day have released a whopping seventy five singles, domestically and internationally, including non-album tracks and promotional releases. An inexact science, selecting singles depends on so many market factors and what-ifs, not to mention pure guesswork; the choices are interesting as an indicator of what hunches a band trusted relative to their place in the market. More interesting is how singles, the lucky ones and the unlucky ones alike, can tell a memorable story about the era into which an album was released. Sing to yourself the most famous Green Day songs—you know them, they were the singles, after all—and you hear a tune, but also see images of a decade, of that summer, that week, that job or that girl or that guy or that car, an era that defines not only the song, but you as well. Which is yet another way to say that music soundtracks our lives, and those soundtracks are virtually impossible to deleter, erase, or record over.

Singles, duly sent forth into the public to make demands, tell only part of the story. Songs that weren’t selected as singles—left behind album tracks—can tell a fuller story; they’re the equivalent of the dark horse in the family, the shy one, or the late-bloomer, anyway the one who wasn’t festooned—or burdened—at birth with glory.

Here are what I consider the best album track from each Green Day album.

Dookie (1994)

The singles: “Longview,” “Welcome to Paradise,” “Basket Case,” “When I Come Around,” “She”

Album track: “Sassafras Roots.”

This was a tough choice because, as we’ll see, Green Day and/or the folks at Reprise were generally pretty good at choosing singles that had commercial appeal and represented an album. The Dookie singles are not only “classics” of the era, they’re Green Day DNA, indivisible form the band’s core identity. But “Sassafras Roots” also captures the band’s jaded, nervy vibe with aplomb, the descending melody in the verse lines graphically evoking a stoner’s long, boring afternoon when suddenly brightened by a potential partner—who’s as blasé as he is. “May I waste your time, too?” he asks sweetly, suggesting a Joey Ramone born a few decades later. We used to call these things Anti-Love Songs, but by the Clinton Era such paeans to disaffection against speed-fueled eighth notes were really the most sincere stuff out there.

Years after Dookie’s release, Armstrong revealed that he wrote “Sassafras Roots” about an early girlfriend, Amanda. She would act as a muse for many more Green Day songs down the years. A couple more are on this list.

Insomniac (1995)

The singles: “Geek Stink Breath,” “Stuck with Me,” “Brain Stew/Jaded,” “Walking Contradiction”

Album track: “Panic Song.”

Unnerved by the mammoth success in the wake of Dookie, Green Day, now balancing young families with intrusive fame and escalating drug use, pivoted slightly with the swiftly-written and -recorded Insomniac, an unruly album stuffed with lyrics about anger, sickness, mental and physical distress, addictions, abuse, disappointment, rejection, bitterness, panic attacks, and disorientation. Its success ensured that songs about despair and self-disgust would play in high rotation in millions of teenagers’ heads.

The choices of single were odd, perhaps signaling the band’s desire to stay “punk” after having sold millions of albums. “Geek Stink Breath”? Well, it was the Grunge Era. “Stuck with Me,” “Brain Stew/Jaded,” and “Walking Contradiction” are great, tough rock and roll, dark and driving, disturbing, even, but “Panic Song” best captures the album’s infected mood. The track opens unhappily with Mike Dirnt’s manic eighth-note bass line, a heart rate on the loose, as Tré Cool gallops alongside on his toms and Armstrong emphasizes the growing anxiety with Who-like power chords and feedback, Cool answering all that with angry snare hits. The thing builds nauseatingly; two minutes in, Armstrong’s scraping his guitar in a frenzy as the band tightens and tightens the sound with no reprieve coming. Lyric sites politely describe the first half of “Panic Song” as an “Instrumental Intro”—it’s really the sonic equivalent of an electrocardiogram, and alarms are sounding up and down the hospital. If you’ve ever suffered a panic or anxiety attack, it’s a pretty fucking disquieting listen.

When the band finally comes roaring in in the song’s second half, the relief is palpable, but short-lived. Armstrong spits out phrases like “self-destruction,” “broken glass inside my head,” and “limp with hate” so when in the last verse he sings about just wanting to jump out, you not only get it, you wanna bail out with him. An overwhelming “feel” song, “Panic Song”’s a disturbing but affecting listen, and one of Green Day’s underrated early tracks.

Nimrod (1997)

The singles: “Hitchin’ a Ride,” “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life),” “Redundant,” “Nice Guys Finish Last”

Album track: “Prosthetic Head.”

This was another tough call. I could have easily selected “The Grouch,” “Scattered,” or “King For A Day,” but I went with the devastating “Prosthetic Head,” an underrated Green Day track nearly buried on a sprawling, eighteen-song album that will always be (in)famous for that song that they played at the end of Seinfeld.

One of Armstrong’s great put-downs, “Prosthetic Head,” a series of sneers directed at an empty-headed poseur, excites itself with its own revulsion. In the fashion of the era, the verses are quiet, the chorus loud, and here the dynamics work really well: the insults in the verses are calmly put forth against Armstrong’s dryly recorded guitar strums and subtle, unobtrusive backing form Dirnt and Cool, until the band can’t be polite about their target’s loud cluelessness for a moment longer, and the gang-sung chorus erupts—a simple but annihilating you don’t know, you got no reply. Who’s Armstrong signing about here? A rival band member? A scenester? An ex-associate? Who knows. If the label fits….

“Prosthetic Head” comes fanged with one of Armstrong’s sharpest puns—the song’s subject is a “Red blooded Amannequin,” an insult worthy of early Elvis Costello—and in its dry and incisive dismissal of vacuous airheads taking up our space and our time, it’s sadly relevant still. I guess every age has its share of posers with loud mouths, but we seem inundated these days. Play loud.

Warning (2000)

The singles: “Minority”, “Warning,” “Waiting”

Album track: “Church On Sunday.”

Green Day released only three singles from the underwhelming Warning, perhaps an indication of the album’s commercial disappointments (relative to the band’s earlier chart successes) and diminishing returns. The early aughts were a strange time for Green Day—though “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” had been a huge, unexpected hit, the song’s success cut both ways, delighting the masses while alienating many of the band’s fans, especially those who dated back to the 924 Gilman Street days. The band was a little bored, and were bickering with each other (a malaise that was ultimately dispersed by the band’s self-willed onstage domination of Blink-182 on 2002’s Pop Disaster Tour, and the unprecedented global success of American Idiot in 2004 and ‘05).

I might’ve selected Warning’s melancholy and evocative closer “Macy’s Day Parade” for this list but, frustratingly, the lyrics never quite cohere with the sentiment, and so I’m going with “Church On Sunday.” I wrote about this song a decade ago (I included the essay in my book Field Recordings from the Inside), and I wouldn’t change a thing today.

“A couple is arguing in their kitchen, battling their way to some kind of truce,” I wrote. “This is the first day of the rest of their lives, he insists to her, and there’s no pretending that everything’s okay.”

The tableau is lousy: he’s a self-described bloodshot deadbeat, and her mascara’s bleeding tears down her face. They’re a young couple facing the fact that ecstatic Saturdays turn to hopeful Sundays turn to remorseful Mondays. As Green Day’s “Church On Sunday” races to its anthemic chorus, the couple lurches toward a compromise: “If I promise to go to church on Sunday,” he says, “will you go with me on Friday night?” It’s a simple question, and the melody makes it hopeful, ascending on the phrase “Friday night.” But the question is burdened by a vexed past—lies, likely, and mistrust, and disappointments, as shared desires and visions pull apart.

…The autobiographical “Church On Sunday” is arguably the first fully adult song that Billie Joe Armstrong and the band produced, an honest rock-and-roll struggle between the excesses of snotty punk nihilism and a mature life devoted to faith and community. The tension in the middle has this young couple in its grip: If I do what you want, will you do what I want? Can we balance this weekend so that it doesn’t topple into hangovers and recrimination? Can this work? He assures her that he’ll earn her respect, but the eternal present tense of the song’s resolution offers little closure. Next weekend is still a long way off.

American Idiot (2004)

The singles: “American Idiot,” “Boulevard of Broken Dreams,” “Holiday,” “Wake Me Up When September Ends,” “Jesus of Suburbia”

Album track: “Letterbomb.”

Another tough call here, as American Idiot is a near flawless album, and the singles that were released evoke the album’s storyline and themes in iconic and memorable ways. “Letterbomb” arrives two thirds of the way through the album, and, as the title suggests, is a missive loaded with explosives. The character Whatshername, based on Armstrong’s ex-girlfriend Amanda, is breaking things off with small-town expat Jesus of Suburbia, whose reckless and self-destructive devolving into his alter ego St. Jimmy is becoming problematic.

The song begins with a “nobody likes you” taunt from Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna—it’s Whatsername, or a self-pitying voice in Jesus of Suburbia’s head—before exploding into the first verse, where presumably having read, or, anyway, clutching Whatshername’s letter, Jesus of Suburbia looks about and sees nothing but destruction, loss, and cynicism. The chorus that arrives sounds as if it’s driving to redemption, but the words spoil Jesus’s mood; Whatsername is splitting (“There’s nothing left to analyze”), but not before admonishing him, in brutally direct terms, that his twin identities, born of a raging father and a forgiving mother, are a lie, an excuse for his shitty and self-harming behavior. And he won’t be her burden any longer.

The songs in American Idiot tell stories of eternal push-pull dynamics so well—leaving home versus returning, ideals versus cynicism, innocence versus experience, love versus hate—that any one song suffers a bit from standing on its own, removed from its narrative role. The rush of the pre-chorus where Whatshername takes down Jesus’s alter ego comes in part from its dramatic role in the story, yet so inspired was the band’s writing in this peak era that songs work individually, also. Look at the worldwide impact that those singles had. “Letterbomb”’s right up there.

21st Century Breakdown (2009)

The singles: “Know Your Enemy,” “21 Guns,” “East Jesus Nowhere,” “21st Century Breakdown,” “Last of the American Girls”

Album track: “Restless Heart Syndrome.”

Another sprawling, operatic rock and roll album, and five more singles. Of course, what I call “sprawling,” another might call “bloated.” 21st Century Breakdown was fated before its arrival to be seen as lesser than or too much like American Idiot, in artistic and commercials terms, which was a tough burden to bear for the band (they’ve characterized the recording sessions as, at times, stressful and unhappy). In the end, the album splits the difference, embracing its predecessor’s thematic and musical ambitions while jettisoning a clear narrative for a wide-screen take on America at the end of the Bush Era. (In the event, several songs from the album were utilized to strengthen the storyline in the American Idiot Broadway musical that ran throughout the 2010s.)

I’m a fan of 21st Century Breakdown, and, frankly, the further it moves out of American Idiot’s considerable shadow, the more impressed I am. Armstrong and the band were still working at a very high level, their appetite for character building and cinematic storytelling still at its peak. The album contains a number of terrific songs that were bypassed as singles, including “Peacemaker,” “Murder City,” “The Static Age,” and “See the Light.” “Restless Heart Syndrome” stands out, one of the band’s greatest songs with some of Armstrong’s most affecting lyrics.

If you were a teenager hanging out at Gilman in the early-90’s and time travelled to the late-00’s to hear “Restless Heart Syndrome,” you’d likely blanche at the opening, with its elegant grand piano and orchestral strings. But the band had been accessing string arrangements and acoustic timbres for some time already. The mood captured here is sorrowful, the solemn tones wholly appropriate for what follows. Armstrong has been candid about his battles with alcohol and prescription drugs, and this song finds the singer at the end of a long, exhausting campaign. He’s on his knees, something vital is missing, and he’s desperate for the pharmacy where his memory might be wiped away with a dose of anti-depressants. Armstrong rhymes “elated” with “medicated.” Do the unhappy math.

The song graphically evokes the sense of aloneness and quasi-paranoia that medicating can create; the singer wonders why I feel so confident, when he needs a place to hide because you never know what’s lurking around the corner. When moving through life in a protective gauze of prescription drugs, living, he implies, feels paradoxically dangerous, suicidal even. The song’s key insights—that “what ails you is what impales you,” that symptoms create victims who then become their own worst enemies—are profound and unsettling, a withering critique of Big Pharma sung in a melody the sweetness of which is belied by the discoveries. It’s the cloud that settles over the song and never lifts. After Armstrong cites the title of “Know Your Enemy”—an entirely different jam, and now forever linked to this song’s sadness—he erupts in a furious, screeching guitar solo that churns things up angrily. But the mood still feels helpless.

Part 2 of “Castaways”—¡Uno!, ¡Dos!, and ¡Tré! through Saviors—coming tomorrow!