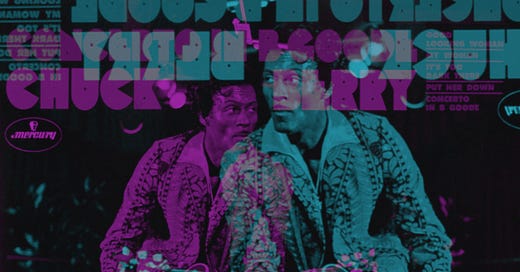

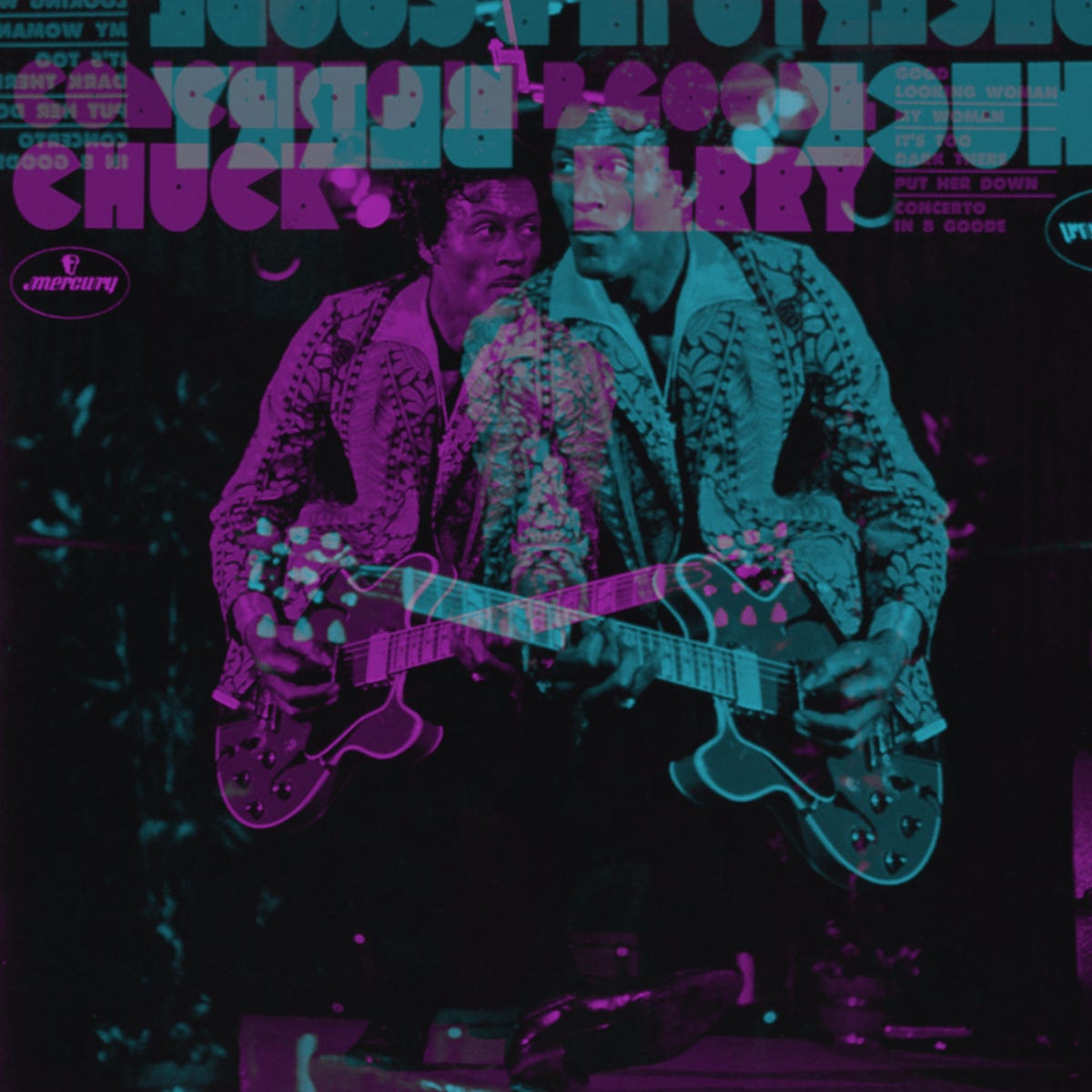

Chuck Berry in the dark

His "Concerto in B Goode" (1969) was sold as a sonic response to a tumultuous era

Sometime in the 1990s I was listening to a bootleg CD of the Beatles’ late-1966 recording sessions for “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Buried deep near the end of one take, I heard what sounded like a random Chuck Berry lick played by George Harrison, a lone formalist stay against the chaos that John Lennon was brewing in his deeply inward, trippy evocation of childhood. I smiled at this, as the band probably did, too. 1966 must’ve felt eons away from 1963, when the Beatles would bust out Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Rock and Roll Music,” or “Johnny B. Goode,” half-aware that they were filtering beloved songs from another era in new and unprecedented ways. I haven’t gone back to that boot in quite a while, and I don’t recall hearing that lick in the two takes of “Strawberry Fields Forever” included on Anthology 2, released in 1996, but I’m fairly certain I didn’t imagine it. And if the riff was a figment of my imagination, I’ll think of it as a kind of ghostly trace, because Chuck Berry never went away.

In June 1969, Berry released Concerto in B Goode, his final album for Mercury Records. Like all of the LPs he released in the 1960s, Concerto in B Goode did not trouble the Billboard charts, nor did its lone single, “It’s Too Dark in There.” A few months later, in September, Berry would perform at the University of Toronto at the day-long Toronto Rock and Roll Revival with, among others, Bo Diddley, Chicago, Alice Cooper, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, the Doors, and, most notably, Plastic Ono Band. There was whiff of a rootsiness in the pachouli-scented air—Credence Clearwater Revival released their hugely successful “down home” albums Bayou Country, Green River, and Willy and the Poor Boys that year. And some fertile genre cross-pollinating, as well—the month Berry released Concerto in B Goode Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash sang a duet on a Grand Ole Opry television special. Just a few years earlier, the notion of the Dylan and Cash joining forces likely felt implausible—one cryptically hiding behind shades, the other offering a gangly, populist grin. In retrospect, of course, their union looks inevitable. Sources were pooling, boundaries greying.

As a music writer, I eagerly seek out yet am dryly skeptical of historical context. No work of art exists in a vacuum, and it’s crucial (and fun) when writing about a song or an album to pull wide and take note of what else was going on around it. Yet I find that it’s too easy to fall under the powerful spell of the Time and Date Stamp, to believe, or anyway imagine, that an entire generation acted in step, the majority of people responding to the same cultural forces in the same way. Lazy films and television shows succumb to this all of the time: pony up for the licensing fees, drop a Top 10 hit from 1967 into a scene where garlanded characters talk to each other in of-the-era slang, and you’ve got yourself some verisimilitude.

The stubborn reality is that many of us walk through our days paying little attention to the cultural moments that future generations might find epochal. Just as many faces go blank in response to the “Where Were You When X Happened?” parlor game as brighten with an evocative memory. The television show Mad Men was, on the main, exceptionally good at subtly dramatizing the way people behaved against the backdrop of history. In “The Grown-Ups” episode in season three a couple of characters squabbled over something petty as Walter Cronkite’s epochal coverage of President Kennedy’s assassination played out on a flickering television set in the background: the historic first unnoticed, and then impossible to ignore.

The second side of Concerto in B Goode is devoted to its title track, all eighteen minutes and forty four seconds of it. Though Berry had released instrumentals before, he’d never issued anything quite like this. The title’s a ham-handed attempt to drag his classic 1957 hit single into the Art Pop age. In the second half of the decade songs were growing in length and pretense; guitar-based tracks were festooned with orchestral strings or arranged “psychedelically,” presented as golden children to greet the dawn of a new era. Some bands and artists bands manfully resisted such symphonious sweetening; others mainlined it. The results were sometimes generic and instantly dated, sometimes inspired and mold-breaking.

As RJ Smith observes in his essential Berry 2022 biography, the end of the 1960s was indeed “a good season for rambles.” Smith notes Muddy Waters’s “controversial psychedelic document” Electric Mud, released in 1968, and Howlin’ Wolf’s “nearly groovy” The Howlin’ Wolf Album. “Wolf famously hated his record,” Smith wrote, “and told the guitar player on the session to go cut his Afro and take that bow-wow pedal and throw it into the lake.” But to Smith’s ears, Berry sounds “like he’s having a blast” with the “bonkers” “Concerto in B Goode,” “all-in as he glides his Cadillac down the autobahn, the wind whipping around his phosphorescent cortex,” adding that Berry sounds as if he’s in “a jolly mood.”

To biographer Bruce Pegg in Brown Eyed Handsome Man, there was plenty to wince at. Pegg describes the title track as “an ill-conceived instrumental jam built around a repetitive bass figure. In this so-called Concerto, guitars came and went, dropping in and out of the mix for no apparent reason, while the same heavy reverb effects that plagued the first side reappeared. The entire piece ended in the same place it began 18 minutes and 40 seconds earlier, without any real sense of composition or progression.” He acknowledges that there are “sections of the piece that were interesting and infectious,” but that they were “few and far between.” Billy Peek, who played guitar and keyboards on the album, candidly remarked to Pegg that Concert in B Goode was “a terrible record.”

Lester Bangs took up the album in the August 9 issue of Rolling Stone. “The Master,” he enthused, “has come up with a record worthy of his reputation.” Bangs unsurprisingly praises the album for its commitment to eternal, basic rock and roll, originated by Berry himself, and for its humor: “Rock is an ailing form without its sense of humor, and Chuck Berry defined a whole comic sensibility.” Bangs is sensitive to those who’d question Berry’s relevancy in the tumultuous, politically-charged summer of ‘69: Berry’s new songs, he acknowledges, “don’t relate to Sixties dope-balling, or the feel of police truncheons crunching into skull-bone”—I’m pretty sure his ears are still ringing from MC5’s incendiary debut Kick Out the Jams, released earlier in the year—“but they do ring true,” a couple of them stylish with “the marvelous old Berry wit, something a great many of today’s owl-faced artrockers would do well to pick up on.”

As for the title track? “For all the thematic and improvisatory repetition,” Bangs wrote, “you can’t help but dig it, because it’s so happy, driving, and exuberant, everflowing with the spirit of life joyously lived,” what Bangs, characteristically, hails as “the essential spirit of our music.” Berry plays “with a natural energy and sense of direction that one never finds in the solos of last year’s crop of overblown ‘jazz-rock’ super-groups.” Bangs ends the brief review with a prediction: “I suspect [Berry will] still be wailing wisely when the current crop of over-publicized Sensations have faded with their forerunners back into the obscure footnotes of the chronicle of our art.” You can do that math on your own.

For what it’s worth, Chuck Berry makes no mention of the song or the album in his 1987 autobiography.

The song title’s a bit misleading (not to mention really corny). What one might call a “concerto,” others would call a jam. Berry produced the recording session at his home studio in Berry Park outside Wentzville, Missouri. Anchored by Kermit Eugene Cooley’s bass riff, Berry, Peck, and drummer Dale Grischer lay down a groove that doesn’t veer dangerously toward a Freak Out, but moves, rather politely, just on the fringes of one. Grischer’s drums alternate appearing between the middle and right in the soundscape—if this was intended as an audio recreation of “a trip,” or anyway something druggily disorienting, it comes across instead as sloppy editing. Berry’s guitar playing moves from lick to lick, some evoking past glories, most noodling around, looking for a place to land, or to elevate from.

Several times Berry introduces a lick after which the band plays a bridge of ascending chords, no doubt reinforced with a curt nod from the Master himself, before settling back into the groove. Berry occasionally moves to a wah-wah tone and there are passages that are drenched with reverb which, particularly in the the last third of the song, sends things into a slightly groovier place. But throughout, Berry’s playing remains relatively tame, as if he couldn’t or wouldn’t commit to seeing just how far-out his playing could sound, and could take the song. (I wonder if Berry was intimidated by Hendrix, or if he studiously ignored him.) As for Peek’s occasional, random organ chirping—I think that kid wandered into the wrong party.

The results are a bit dismal; the drugs wren’t that good. “Concerto in B Goode” might’ve worked as background music in a scene in an exploitation flick: a groovy party where a drug deal may or may not go down, where a fight just might break out. That’s about as dangerous as Berry and his band get here. In his liner notes to the album, Richard Lochte does his best to sell the track as “a remarkable example of Berry’s virtuosity,” an “amazing instrumental,” and a “brilliant blend of blues and country and acid rock. A blues-rock concerto!” Lochte interestingly describes the song as a version of “Johnny B Goode,” rather than a new original song. I only wish that Berry had written lyrics for that tale!

In the event, the album’s single “It’s Too Dark in There” ends up evoking the alarming strangeness and dangers of the era far more graphically than does the self-conscious “Concerto.” Ambling, lazily mid-paced, loose-limbed, the song tells the story of a girl (“a sheltered chick,” as Bangs describes her) who’s frightened of the dark. She balks at a lightless country road and at the stark night sky above it, and also at a house party where the singer takes her, where “it was really out of sight / It was about forty people dancing under one dim light.” (The tunes ends with a dirty joke, naturally.) Who knows when Berry wrote “It’s Too Dark in There.” It might’ve sat around for a while, a story he couldn’t find a melody to, or the other way around. But I can’t shake the era-specific wah-wah guitar in the verses—sounds to me like Chuck picked up some trippy licks back at that dimly-lit, funny-smelling party. He may not have been responding explicitly to the newness around him in the summer of ‘69, but it’s hard to lift him and his stoned-sounding band out of that picture.

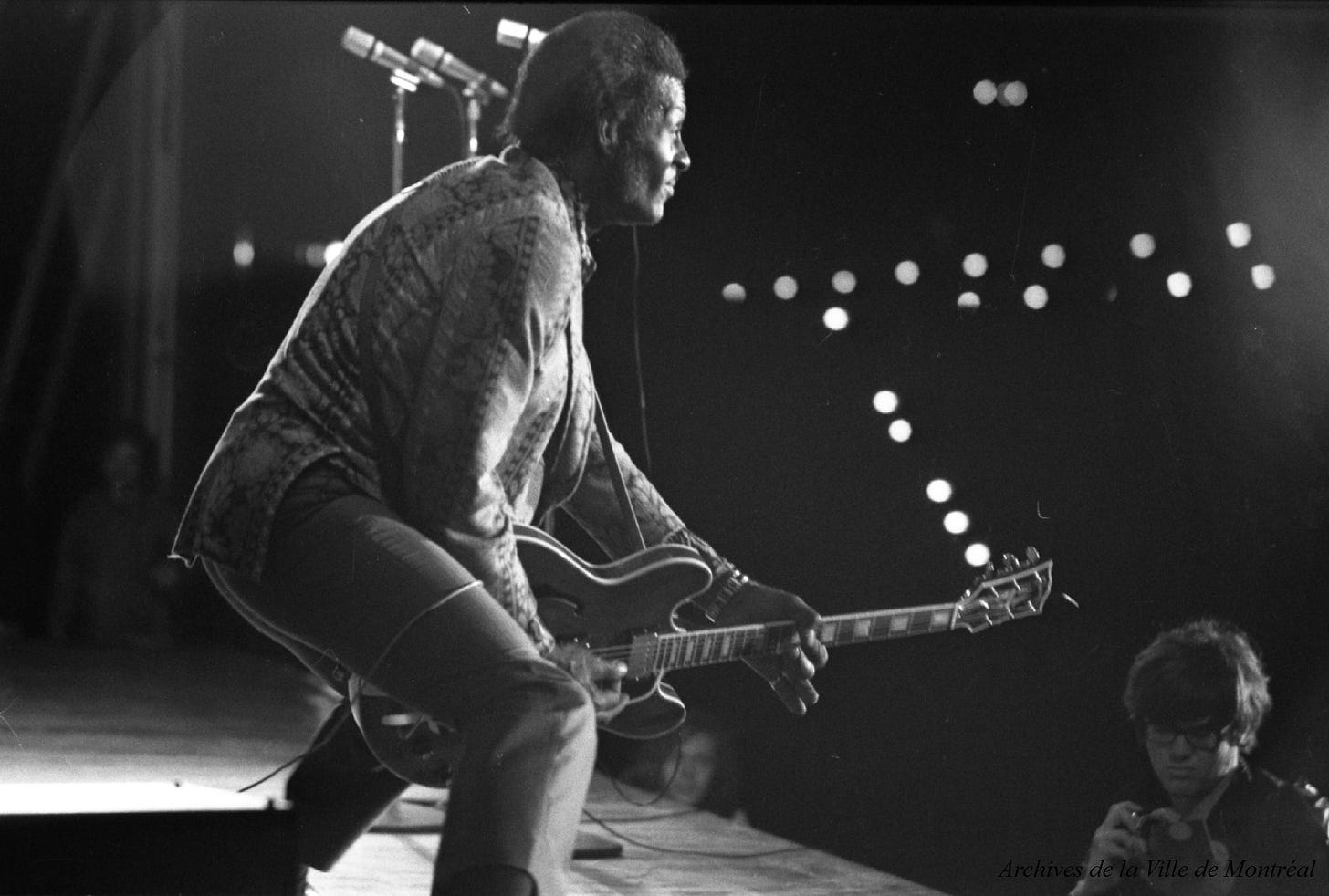

“Spectacle du chanteur et guitariste américain Chuck Berry à la Place des Nations, dans le cadre du Festival Rock & Roll. - 4 juillet 1970.” Photo de M. McDonald. VM94-TDH70-135-033. Archives de la Ville de Montréal via Flickr

New Haven Arena in 1972... The same venue where Jim Morrison was arrested (for the first time) onstage: https://whynow.co.uk/read/when-jim-morrison-was-arrested-on-stage-for-inciting-a-riot

Loving these rambles into the stranger byways of artists I thought I knew!.....