“You’re never going to kill storytelling, because it’s built into the human plan. We come with it.” Margaret Atwood

“In the beginning was the word…closely followed by a drum and some early version of a guitar…. The heart of a lyric for me has always been anchored in an experienced reality…. So in answer to the question I am most often asked, ‘Are these incidents real?’ Yes, he said, Yes Yes Yes.” Lou Reed

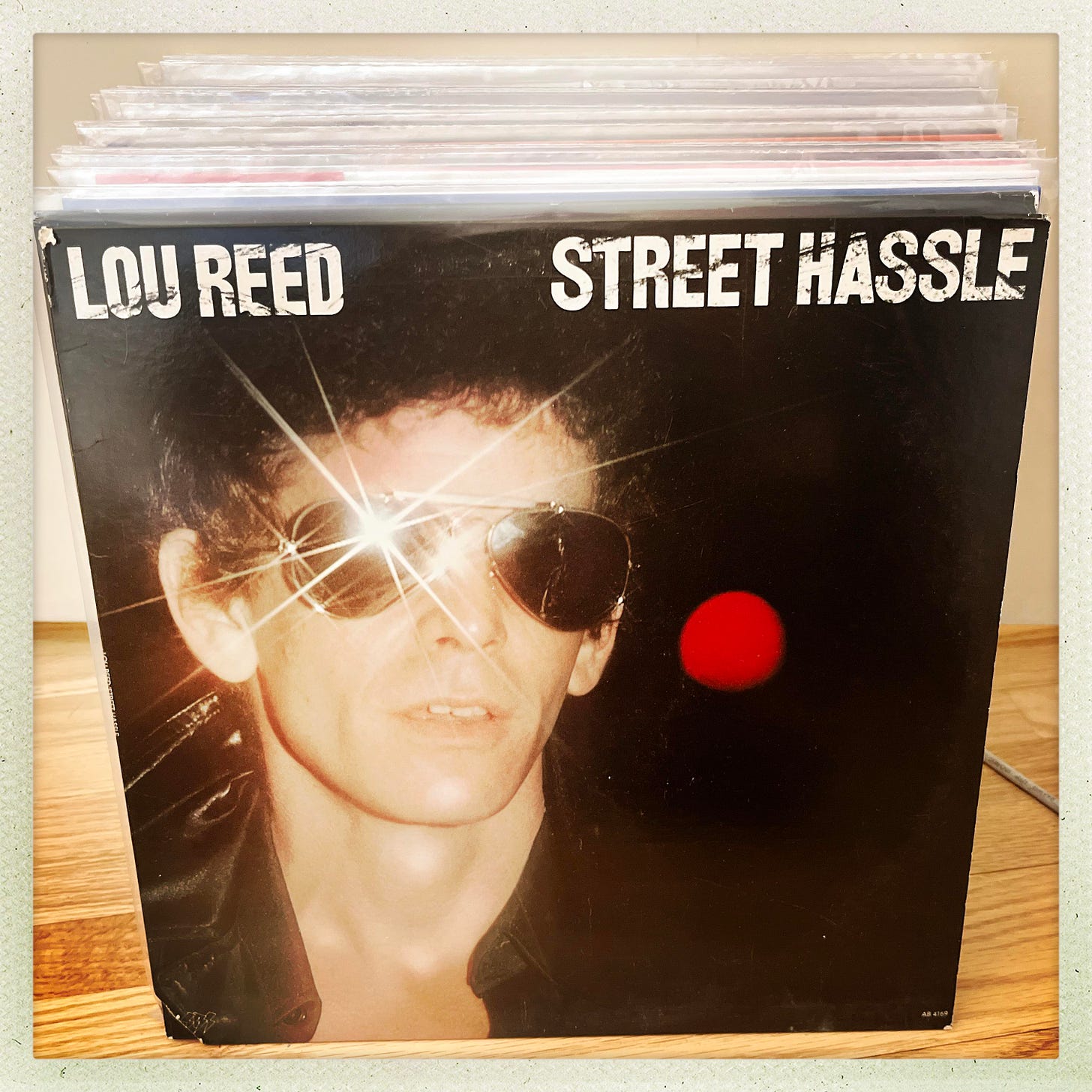

In 1978 Lou Reed released Street Hassle, a blend of live and studio tracks. By then, Reed has been channeling “Lou Reed” for many years. Fans understood that in embarking on an album with him they’d either choose to surrender themselves to whatever unruly blend of grit, fantasy, and glamour Reed was trafficking in, or they’d listen at an ironic, skeptical remove, on guard against being conned yet always open to surprise and transcendence.

Street Hassle’s an uneven album: “Gimmie Some Good Times,” the opener, is a cheeky sendup of the Reed mystique, knowingly fun but a bit of an F.U. with diminishing returns. To sing “I Wanna Be Black” with a wink and stuff the song with crude, racist stereotypes was suspect in ‘78; now, the song’s virtually unlistenable. “Dirt,” “Shooting Star,” and “Wait” are stronger tracks, Reed better balancing his character/role and untutored vocals with deeply-felt, if always grimy, sentiments and some street rock groove. The live tracks recorded in Munich, Wiesbaden, and Ludwigshafen, Germany were taped with Binaural recording, a then-cutting edge technology developed by Manfred Schunke that involved inserting recording mics into a mannequin head with physiologically-accurate ear canals in order to reproduce a more authentic stereo experience. To my (actual) ears the effect on Street Hassle was underwhelming, murkily unedifying even on headphones.

(If you really want to hear what binaural recording was capable of, dig the opening of KISS’ “Detroit Rock City” on headphones. The recording aurally “moves” the listener from idly washing dishes at the kitchen sink out to the front seat of a car, radio on and engine revving, the night ahead; the effect is uncanny, capturing a heady, mid-70s ambience that blew my mind when I was a kid.)

The title song remains the album’s centerpiece, an eleven-minute mini-opera of urban despair. Against a string quartet (arranged by Aram Schefrin) and, later, guitar and bass, Reed narrates a fragmented story of love and loss in three parts. Throughout, the quartet works a variation of the same notes, evoking something that’s part jaunty, part ominous. The opening vibe’s theatrical, for sure: the strings conjure a stark, dimly-lit stage on which something’s gonna happen, soon. The album came without a lyric sheet, so the listener couldn’t jump ahead and the scan the words during the song’s opening minute and a half, as the strings play. They could only wait for the lights to rise and a scene to unfold.

Reed enters in “Part 1: Waltzing Matilda” and talk-sings the story of a woman paying a man for sex. Throughout, the genders of the participants can seem fixed one moment, fluid the next, a slippery spectrum where so many of Reed’s dear friends and fictional characters lived along, as did Reed himself. She, the one who’s buying, is “queen for a day,” the cross-dressing or trans implications clear, her “oh what a humping muscle” gasp a moan that likely gazes in two directions at once. There’s tenderness in the room, and Reed narrates with a vulnerable quiver in his voice, rawly, as if he’s touched, or at least curious and laid bare because of his curiosity. His trademark, “wild side” atonal delivery threatens to lift into melody on occasion but Reed, the dry, ironic chronicler, keeps at strict attention.

One of them’s flirting, or they both are, swept away by the lust and commerce that brought them together, but also by sympathy and surprise, a revelation that turns what might’ve been tawdry or shameful into something hot and exalted:

Cascading slowly, he lifted her wholly and boldly

Out of this world

And despite people’s derision proved to be more than diversion

…He entered her slowly and showed her where he was coming from

And then sha la la la la, he made love to her gently

It was like she’d never ever come

People’s derision, not their own. “Neither one regretted a thing,” Reed says smilingly as the story ends. Throughout, the string quartet plays on, their sprightly, though tone-darkened, score conjuring a kind of Goddess of Naturalism that’s standing to the side of life, soundtracking the ordinary and extraordinary goings on that occur there, occasionally glancing over mildly, indifferently, and never offering judgement.

But the story isn’t finished. A lone female voice lifts or descends from somewhere, disembodied mmms, ohs, and oohs that signal the start of “Part 2: Street Hassle.” Are these lovely sounds the wordless drift-ends of an orgasm, bliss settling into the realities of the moment? Or something else? The quartet strikes up the familiar phrase again and the voice returns, in chorus now, singing the phrase slip away. The listener’s in the dark as a new voice enters, still Reed’s yet different:

Hey, that cunt’s not breathing

I think she’s had too much of something or other

Hey, man, you know what I mean?

I don’t mean to scare you

But you're the one who came here

And you’re the one who’s gotta take her when you leave

Slip away, indeed. The song’s got a dead body on its hands now, grimly received with the brutal practicality required in the moment: get her the fuck outta here before the cops come. It doesn’t matter who’s talking here—a super, a landlord, a pimp, a rando—what matters is the cruel common-sense in the tone, the knife-edge demands to avoid a hassle at all cost. Reed nails the voice—he was one of rock and roll’s great actors—and that voice’s dry requirements:

I’m not being smart or trying to be cold on my part

And I’m not gonna wear my heart on my sleeve

But you know people get all emotional

And sometimes man they just don’t act rationally

Oh, they think they’re just on TV

“Why don’t you just slip her away?” he asks, in a moment of atrocious kindness, the phrase slip away now cold to the touch. Defensively, he wishes that there had been something he could’ve done to save her, but “Oh, when someone turns that blue / Well, it’s a universal truth / Then you just know that bitch will never fuck again.” Sweating it out, he admonishes the man for bringing shitty drugs to his joint, and offers him a queasy, endgame rationale—“By morning, she’s just another hit and run”—that sums up the song’s worldview and, in effect, becomes the credo of all those who are marginalized:

You know, some people got no choice

And they can never find a voice

To talk with that they can even call their own

So the first thing that they see

That allows them the right to be

Why they follow it

You know, it’s called bad luck

The stage lights cut out on that last line. Reed plays with shifting points-of-view in “Street Hassle, and seven minutes in when we hear that final, heartbreaking verse in Part 2, we’re not sure who’s talking, but whoever is has morphed into a silhouette. The bittersweet truths they speak are worldly, weary, and staggeringly poignant, the very blend of meanness and generosity. The Goddesses of Naturalism play on.

Forty-six years later, we know instantly who’s speaking as “Part 3: Slipaway” begins. In 1978, we likely didn’t. It’s a different voice, not Reed’s, and there’s no credit in the album’s liner notes.

In the fall of 1977, Bruce Springsteen was struggling mightily. Hounded by lawsuits, pressured to follow up 1975’s Born to Run with an album as equally epic, he’d finally had been allowed back in the studio and was working on protracted, agonizing sessions at the Record Plant, where Reed was recording “Street Hassle.” Springsteen, seven years younger than Reed, was always wrestling, like Reed was, with how best and most respectfully to sketch his street characters. The two songwriters were kindred spirits, of a sort—one was steeped in irony, the other in earnestness, yet both were highly performative storytellers of the disaffected, those born with low ceilings of expectations erected by gender dysmorphia and drug abuse on one hand and family dysfunction and blue-collar fate on the other. (The truth’s richest in the middle.)

“Out went anything that smacked of frivolity or nostalgia,” Springsteen wrote in his essential memoir Born to Run about the recording sessions that produced Darkness on the Edge of Town. “Pop needed new provocations and new responses. In ’78 I felt a distant kinship to [punk rock] groups, to the class consciousness, the anger. They hardened my resolve. I would take my own route, but the punks were frightening, inspirational and challenging to American musicians. Their energy and influence can be found buried in the subtext of Darkness on the Edge of Town.” The album was Springsteen’s “samurai record, all stripped down for fighting. My protagonists in these songs had to divest themselves of all that was unnecessary to survive.” He added, “I determined that there on the streets of my hometown was the beginning of my purpose, my reason, my passion.”

So, obviously Reed was a fan, to a point. He knew and admired Born to Run and once or twice gave The Boss a shoutout from the stage. Allegedly, Reed felt that he needed a voice other than his to narrate the stark opening verse of “Street Hassle”’s third and final section. Reed, or someone else, knew that Springsteen was working in the building. As for the story’s moving parts—who invited who, and where precisely the invitation was proffered—accounts vary, but however it happened, two great chroniclers of street drama came together one evening as Springsteen found himself at a mic in the studio with Reed and co-producer Richard Robinson looking on. Though in his own songs Springsteen rarely explored the kind of lurid and decadent streetscapes that Reed routinely trafficked in, he understood well the kinds of marginalized folk Reed sang about.

The song’s familiar phrase arrives via a distorted bass, joined in a few moments by an ghostly jangly piano, a dry-as-dirt answering guitar line, and, eventually, the quartet. (An oddly-timed snare drum sounds, too, a toll of sorts.) Grief’s everywhere in the song now, the loss felt in the death of not only a person but of the limits of freedom of choice when you’re an outsider. On top of this ambience, Springsteen murmurs, in lines that he could’ve composed himself, about the lies that the dead woman told her friends,

‘Cause a real song

The real song she won't even admit to herself

The beating in her heart

It’s a song lots of people know

It’s a painful song

With a load of sad truth

But life’s full of sad songs

“A pretty kiss or a pretty face can’t have its way,” Springsteens says, before ending with the line that Reed supposedly wrote for his fellow songwriter: “Joe, tramps like us, we were born to pay.” Springsteen swallows the payoff line, or was mixed low in post-production, but the in-joke’s there, only it’s not funny. It’s tragic. (Springsteen would have a lot more fun at the Record Plant with another uncredited contribution. He added a lusty “one, two…one, two, three, four!” on the Dictators’ raucous and hilarious “Faster and Louder” on Bloodbrothers, released, as were Street Hassle and Darkness on the Edge of Town, in 1978. The many moods of a rock and roll lifer.)

At the start of the Darkness sessions, in fact at the very start, Springsteen recorded a “Breakaway,” a song he wisely revisited in 2010 for the The Promise box set. “Breakaway” is, to my ears, one of Springsteen’s most sublime throwaways, an aching song about fuck-ups, regrets, and salvation on the streets. Reed couldn’t have known about the song, and yet , from this vantage point, the Breakaway/Slip Away alignment feels written in the stars.

The last verse in “Street Hassle” is overwhelmingly melancholy. “Love has gone away,” Reed says, the closest he comes to singing, “and there’s no one here now, and there’s nothing left to say.” He misses him, he confides, the pronouns slipping out of a sure grasp and requiring that we reevaluate the tableau we thought we knew—who’s wearing a mask to find their real self? Does it matter? Again, flatly: “Love has gone away / Took the rings off my fingers.” And there’s nothing left to say, except, “I need your loving so bad, babe / Please don’t slip away.” By now that phrase has become song’s perpetual motion machine, arriving in the singer’s, and the song’s, last line as, finally, pure sound and ache. Like those “sha la la la la, sha la la la la”’s throughout, which move from the sounds of deeply-felt pleasures to the sounds of a heartless kiss off.

Another item from this era: while promoting Street Hassle Reed had been invited to make an appearance on The Midnight Special, hosted that week by Flo & Eddie. When the producers heard “I Wanna Be Black,” they blanched, and Reed pulled out of the gig in protest. In a unique move, Flo & Eddie then invited Reed onto the set to discuss the situation. I don’t know what drugs were or were not circulating in Reed that evening, but he was unusually relaxed, open, and agreeable throughout the revealing conversation.

Flo begins by calling out Reed on the character of “Lou Reed,” and Eddie wants to know how much of it all is theater. “What’s the guy order at Denny’s? I mean, is that the same guy?”

Reed: He would eat at Denny’s. I wouldn’t. [laughter]

Eddie: Ah, so it's a different Lou Reed.

Reed: No, the thing is, the Lou Reed character, as I see him, goes up to a certain point. And I disagree with a lot of, I mean, there are a lot of different Lou Reeds on [Street Hassle], I mean, sometimes espousing a point of view that’s contradictory, say, to the next track…

“I mean, it can’t all be the same person,” Reed adds. “People don’t seem to realize that.” He posits a likely scenario wherein, say, Reed might choose a gold-plated lighter, whereas “Reed” would chose a cool, black and silver one. “I’m very aware what he does and what he’s up to,” Reed deadpans. (“We have meetings,” he says, sounding like a Borscht Belt comic. “No, seriously, seriously.”) He claims that he doesn’t find “I Wanna Be Black” all that offensive. “Why would anybody want to shock somebody else?” he asks his hosts. “I mean, what is the kick in that? To sell records? Well, obviously it doesn’t have that effect. It keeps my record sales down. And so unless I’m into some strange kind of aberrant masochism….” He trails off, adding,

I just find it, for convenience sake, easier to to, like, separate myself from the image, from the creation of the thing…for other people’s sake. Sometimes, like, they'll talk to me as though I’m him. And it just makes it a lot easier because sometimes I stop and say, hey, wait a minute, look, you’re…

Eddie: You’re speaking to the wrong guy now…

Reed: Really, you know, I don’t want to get polysyllabic with you, I don't want to do an erudition trip on you and get into all kinds of hassles with like you talking to me, like, you know, don't confuse me with that, you know…

Flo asks Reed if he pulled out of performing on The Midnight Special as a publicity stunt or if he genuinely felt that he couldn’t perform. “Yeah,” Eddie leans in, “where’s the theater part stop as far as this character goes?”

“No,” Reed answers Flo, “because I’m very consistent, surprisingly enough. In certainly, at least one, respect, and that is I’m true to [the “Lou Reed” character]. Yeah.”

Eddie: “Loyal?”

Reed: “I believe in him. I believe in what he does. You know, I believe in what I do. And I’ve always been that way. It’s like, you know, it’s one of the reasons I like myself, that I’m faithful to it.”

Over the years, critics and biographers have unearthed the likely autobiographical touchstones for “Street Hassle”—the death, in 1975, of Eric Emerson, an Andy Warhol/Max’s Kansas City regular; the demise of Reed’s romantic relationship with Rachel Humphreys, a trans woman—yet what matters more than the song’s origins is where the song takes us. “Street Hassle” headily evokes the grit and glamour of late-70s New York City, and the characters who live and haunt certain parts of the city, but touches eternal stuff, too, and has moved and resonated with listeners around the globe. Interestingly, in 1991 Reed removed Part 3 of “Street Hassle” when he included the song’s lyrics in his book Between Thought and Expression: Selected Lyrics of Lou Reed. He also often skipped the third part when he played the song live. Was that because he no longer identified with the lyrics, or because he identified too closely?

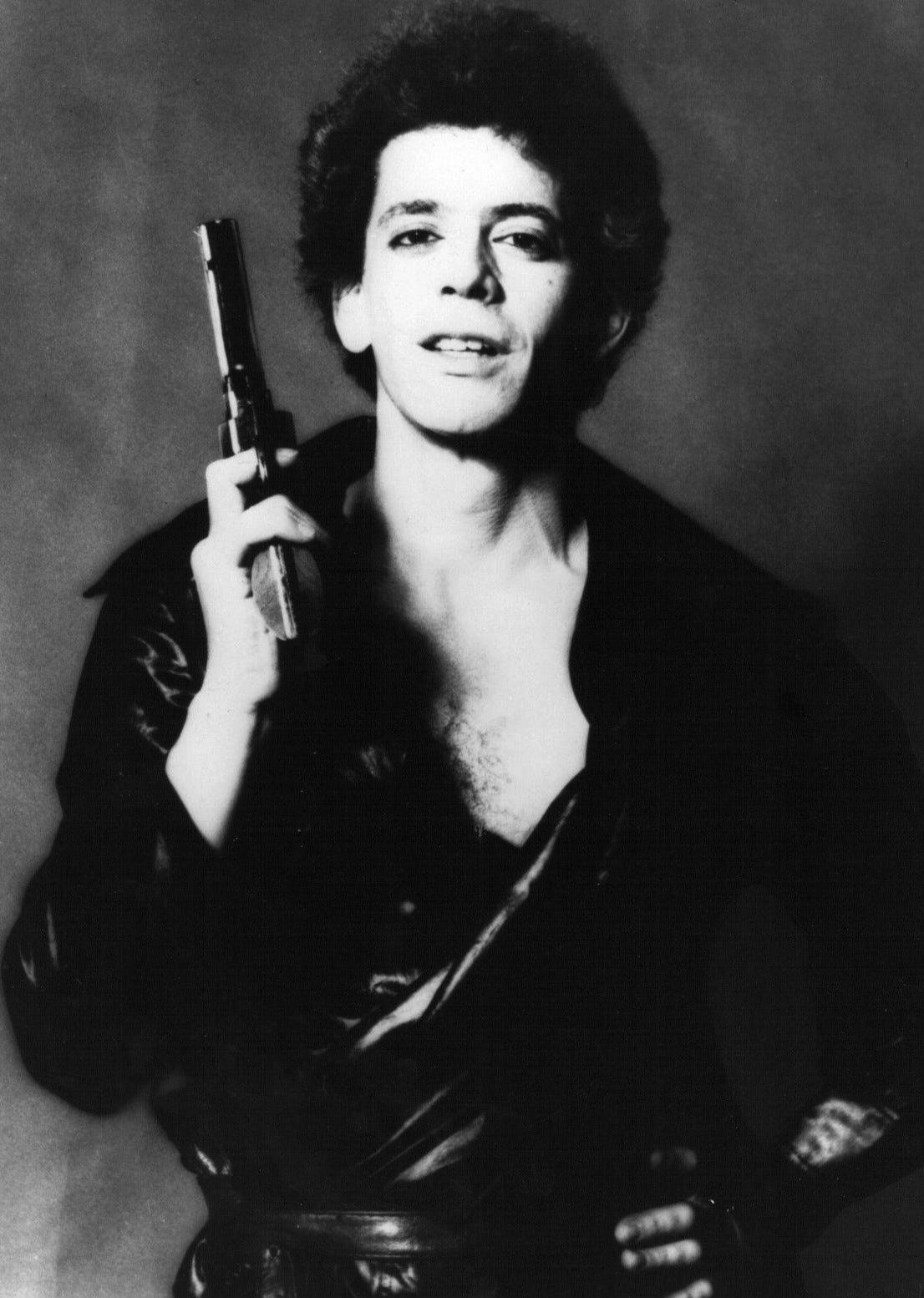

“Lou Reed 1977” via WikiMediaCommons/Public Domain

Great read. I like the live versions of Street Hassle I've heard from the 1978 tour. He snarls the line “Bad Luck” making it more of an indictment, and the bass takes off. Sometimes, I try to see it all as one piece, and other times as a triptych. It almost always demands repeated listenings to take it all in.

Another great read. I always love these types of details in your writings:

“The album came without a lyric sheet, so the listener couldn’t jump ahead and the scan the words during the song’s opening minute and a half, as the strings play. They could only wait for the lights to rise and a scene to unfold.”