Count them as they fall

Elvis Costello's "Big Tears" began as a reaction to a violent film, and then went places

The songs that Elvis Costello and the Attractions recorded in 1977 and 1978 feel as alive and dangerous now as when they were first let loose on a startled public. “No Action,” “This Year’s Girl,” “The Beat,” “Pump It Up,” “(I Don’t Want To Go To) Chelsea,” “Night Rally,” “Radio Radio,” “Tiny Steps” are at turns angry, submissive, challenging, and impotent—all in a day’s work. They incisively dramatize the wounded persona, so cuttingly articulate and prone to lashing out, that Costello perfected in the first decade or so of his career. (Frank Rose in the Village Voice memorably termed this persona the“Avenging Dork.”) “Lipstick Vogue,” as I wrote here a few years back, is a thunderous performance that you can never quite catch up with that says everything you’re feeling in a moment of passion.

Costello and his band—Steve Nieve on a Vox organ, Bruce Thomas on bass, and Pete Thomas on drums—recorded “Big Tears” in January 1978 at Eden Studios in London during the sessions for This Year’s Model. Costello has since described the song as one of those that “got away during this frantic time” and as “the only genuine outtake” from the sessions. “I cannot imagine why it did not make the actual album,” he mused in the liner notes for the 2002 reissue of This Year’s Model and, well, neither can I. Stronger, to my ears, than several songs that made the final cut (“You Belong To Me,” “Hand In Hand,” “Living In Paradise”), “Big Tears” would’ve slotted in quite nicely on an album obsessed with social and personal violence. In the event, the song, wonderfully recorded by producer Nick Lowe and engineer Roger Bechirian, was released as a b-side to “Pump It Up” on June 10, 1978.

Costello’s opening riff is simple, unassuming. It’s only when Pete Thomas’s echoing wallops on his tom drum and Nieve’s descending organ notes enter that we truly recognize we’re in a Costello song. The organ gives that sickly blend of circus and sideshow, a happy sound that’s somehow unnerving too; Bruce Thomas’s bass is round and assertive, anchoring things yet ever restless, curious in the wandering verses to explore side alleys and enter half-opened doors. Costello spits out the lyrics in his early style, as if he’s being burned in real time by their corrosiveness, and the song builds to a impossibly tense finish, the singer demanding—“Tell me! Tell me!”—that we answer the song’s central question, Who’s been taken in? At three minutes, it’s emotionally rending.

There’s a second guitarist making some noise in all of this, too. “I thought that The Clash were a really great rock and roll band, and although this opinion was most definitely not shared by some of The Attractions, I invited Mick Jones to play on one of our sessions,” Costello wrote in those ‘02 liners. “Despite the fact that his bandmates didn’t approve of the idea either, the plan was for him to add another guitar to ‘Pump it Up’.” He added, “However, he made much more difference to ‘Big Tears’.” Jones was running white hot in early 1978, his band between their recording sessions for the “Clash City Rockers” and “White Man (In Hammersmith Palais)” singles, though you had to hunt on the back sleeve of the 45 to find his credit, which ran vertically.

Costello remarked that Jones’s guitar part on “Big Tears” “sounded like police sirens.” It’s a fantastic observation, and an accurate one—I can hear sirens behind the line “When you’re lying in your coffin” in the first chorus, and during the song’s final bars—but I especially love Jones’s playing behind the agonizing couplet that comes later, “You wouldn’t even like me if you'd never had a drink / You wouldn’t even like me if you never stopped to think,” where his strident, off-kilter lines mimic the fever in your head when you wrestle with righteous anger mixed with self-disgust.

Costello’s remark about police sirens is revealing in another way. In the liner notes to the 1989 compilation Girls Girls Girls, Costello remarks in an aside that the story line in “Big Tears” was “borrowed from the film Targets.” Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, released in the tumultuous summer of 1968, Targets is a chilling and prescient tale of two men, fading horror movie actor Byron Orlok (Boris Karlof, playing a character loosely based on himself) and a mild-mannered young man who harbors violent impulses, Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly). [Spoilers follow.] Bogdanovich weaves the two narratives, at times with a heavy hand, to suggest a passing of one generation’s understanding of horror to the next. Orlok wants to retire because he feels as if he and his brand of horror movies are relics, irrelevant to the youth of the new culture where anything goes; meanwhile Thompson, unable to suppress his violent tendencies, snaps and murders his wife, mother, and a delivery boy, climbs an oil storage tank to shoot at passing motorists, and then in the film’s climactic sequence hides behind a screen at a drive-in movie theater—where coincidentally Orlok is making a promotional appearance—where he picks off unsuspecting moviegoers in their cars.

Despite a somewhat lame and ideologically conservative ending, Targets is a genuinely riveting and disturbing film, well-directed with several superb set pieces, especially on location in Los Angeles. It’s an unblinking look at the lone mass shooter figure with which we’ve become all too familiar in recent decades. (The character of Thompson was based on Charles Whitman, who in 1966 killed more than a dozen people from atop a tower on the campus of the University of Texas.) Here’s the IMDb page featuring the movie poster. And if you’re interested here’s the original trailer, that, like most trailers, sensationalizes the story while flattening it considerably.

Costello filters Targets through a prism. Where will it go? Somewhere cinematic, naturally. He evokes the film explicitly in his shocking opening verse (“Everyone is busy with the regular routine…”) but then, as is his wont, he ricochets off the source material. The second verse begins with a typically obscure reference to capitalism (“new boss automatic clause”) but two lines later we get vintage Costello—

Always fascinated by the weird edge of town

Come home disappointed every time they put you down

—where the “you” is someone other than the singer, or the singer as seen by others; either way, they’re wrestling inside a knot of lurid curiosity and bitter embarrassment. By the spiteful third verse—

You wouldn’t even like me if you’d never had a drink

You wouldn’t even like me if you never stopped to think

Standing in the shadow, turning wives to widows

Don’t you know?

—are we inside the perversely rationalizing head of a sniper, or are we in an ordinary someone’s home where they’re duking out yet another bout of emotional cruelty with another. Remember, this is the songwriter who announced early in his career that all of his songs were about “revenge and guilt.” The through line of violence in “Big Tears” isn’t limited to bullets fired in the public square; sometimes the most deadly blows we strike aren’t physical at all, and we often cry the biggest tears in the privacy of our own homes.

In his sprawling 2015 memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink Costello offered several interesting glosses on the autobiographical impulses behind his songs. “I changed every ‘I’ to ‘we,’ so as to share the blame that was entirely my own, and then changed ‘I’ to ‘he’ to further cover my tracks,” he wrote candidly, and “For all the appearances that these songs were a diary or a confession, I’d say that real life was much more harrowing and happens in slower motion than its dramatized form in song.” “Big Tears” is personal for Costello in the sense that the brilliant “Man Out of Time” from Imperial Bedroom (1982) was personal: that song began as a witty response to a report of an English cabinet minister hiding out somewhere weathering a sex scandal storm, and as is his compulsion, Costello went inward, tracking similar emotional misdemeanors in his own sorry life, however disguised. It’s notable that he used to cover Leon Payne’s harrowing “Psycho,” a murder ballad. Perhaps it was only under cover of a cover that Costello could truly get into the headspace of such a man.

I’m curious as to when and where Elvis Costello watched Targets a decade after its release. At a London art film house? A college campus in United States in 1977 on the first tour with the Attractions? I like that last idea, because I can imagine Costello seeing the film between gigs somewhere, and then climbing back into the band’s cramped van, struck by Bogdanovich’s violent and uncompromising story. I bet for Costello, his guitar and pen in hand, those long U.S. highway drives were made even stranger and spookier. (John Ciambotti, the bass player for Clover, the American band that backed Costello on his debut album, remarked to biographer Graeme Thomson, [Elvis] was so prolific, he could write a song while watching a movie.”)

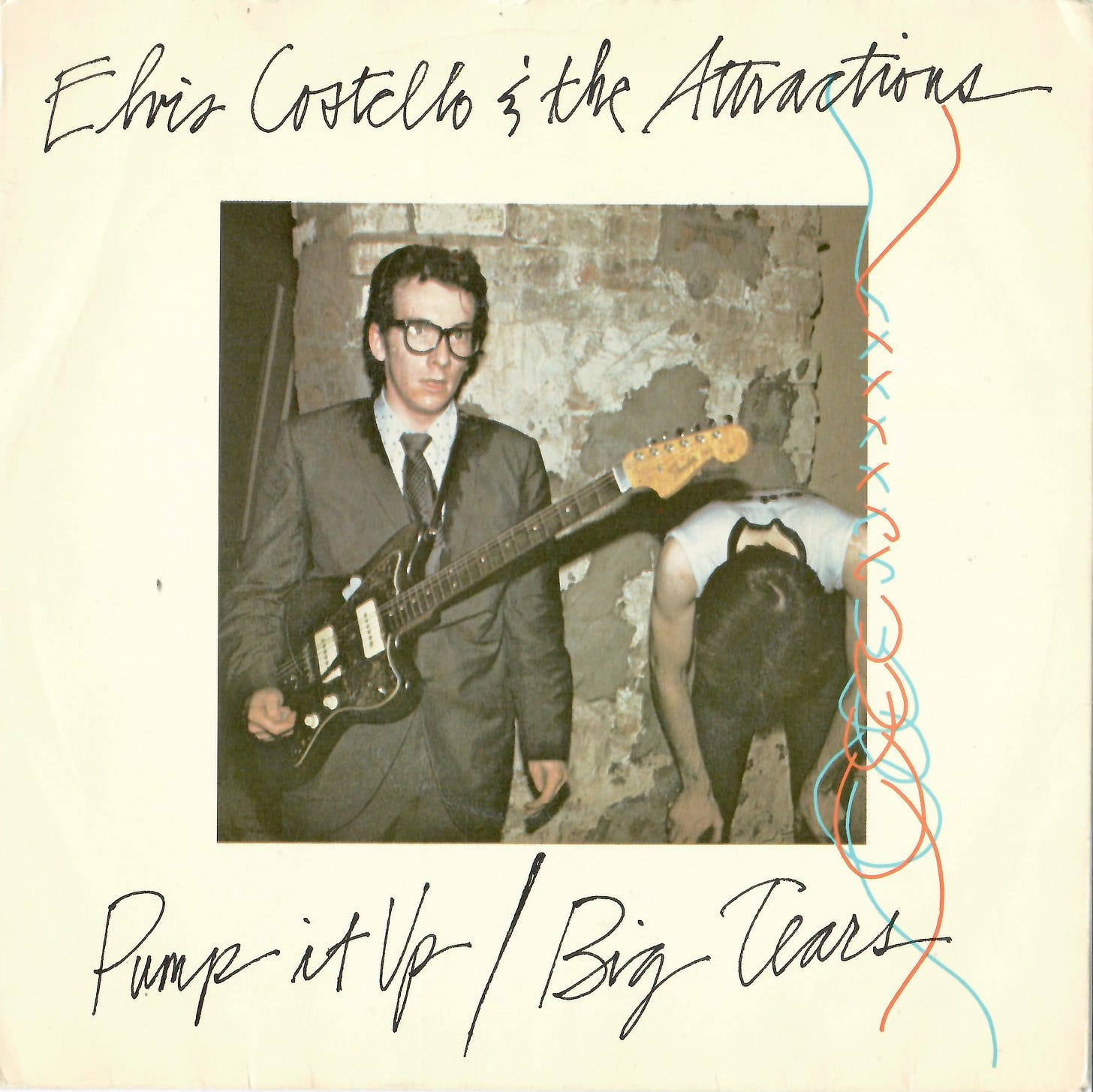

The photo on the sleeve is a classic: a shot of Costello and either Nieve or Pete Thomas against a distressed wall captured in a moment of high intensity. Costello looks dazed; his band member leans over, exhausted, spent, catching his breath. Such was the coiled energy of the band in those days that it’s impossible to know whether the photo was taken after or before a show.

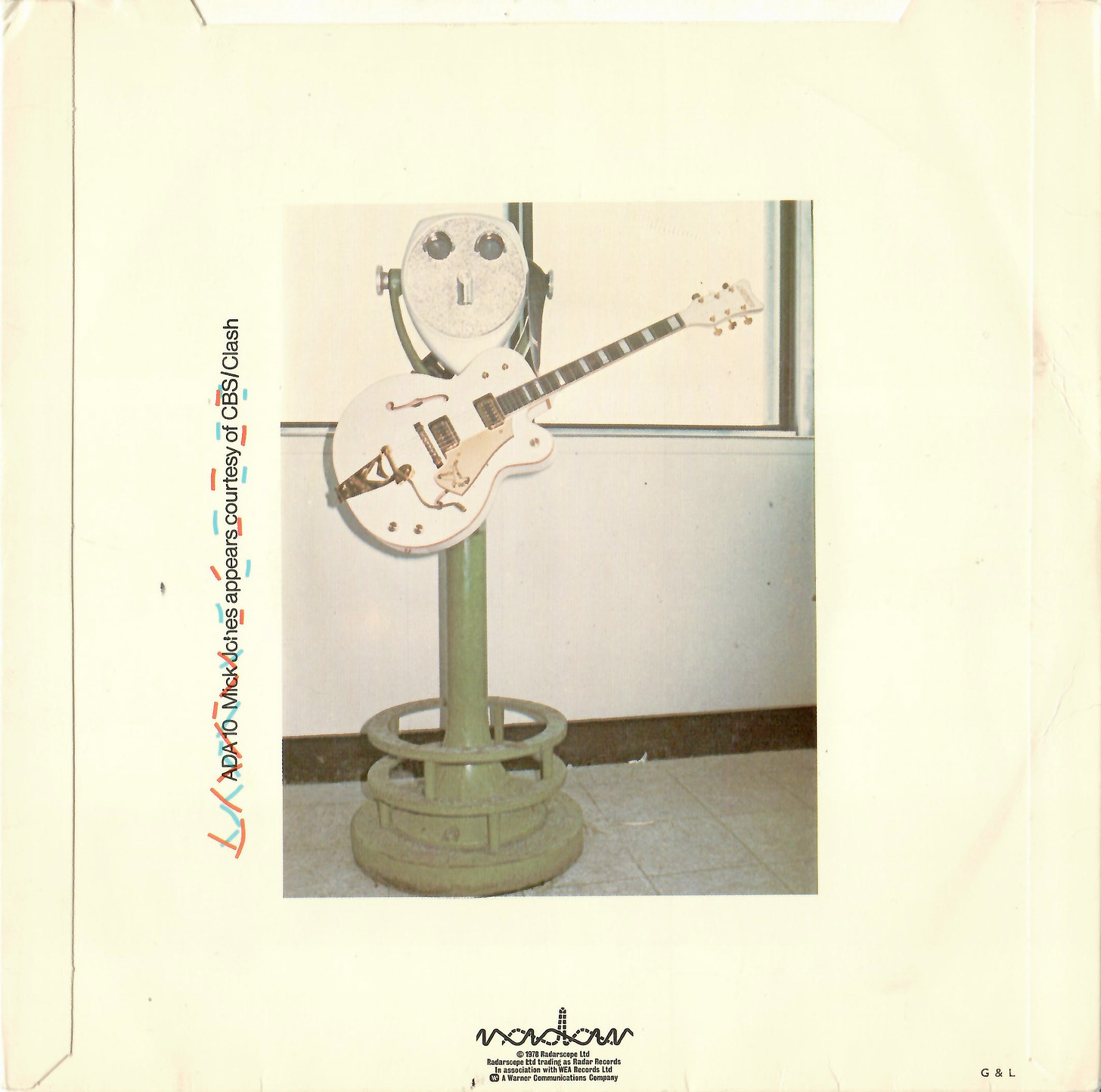

The back sleeve of the 45 tells its own story. I love this image of a slyly smiling viewfinder scope with a guitar draped around its neck. Artist as voyeur, which I believe Costello has listed among his job titles. Pity I can’t credit the photographers.

David Gouldstone in his book God’s Comic describes “Big Tears” as a “macabre song about the meaninglessness of life” and “the fact that death can strike at any time,” adding that the song’s a “chillingly effective memento mori.” In his book Elvis Costello in the Kill Your Idols series, David Sheppard succinctly terms the song an “upset, minor-key anthem.” I like that.

Costello selected “Big Tears” for inclusion in his ripping 2007 compilation Rock and Roll Music, a collection that “proves that at his peak Elvis was a thrilling, hard-edged rocker, particularly when he was backed by the Attractions,” Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote at AllMusic, adding that the comp was intended “for the skeptical neophyte who never believed that Elvis Costello was a punk rocker.” Costello hit the road that summer in support of The Best of Elvis Costello: The First 10 Years, and I caught him and the Imposters (featuring Nieve and Pete Thomas) at the 9:30 Club in Washington D.C.. Costello played over 30 songs in front of a sold-out and knocked-out crowd, committed, tearing into his past, revisiting the well-known and the obscure, singing and playing with intensity and sincerity. I don’t think he even addressed the crowd until the fifth or sixth tune; I don’t think he ever removed his shades. I'd wanted to hear him sing “Riot Act” for many years. My buddies and I were close to the stage and it felt historic. Nearly two decades later it still ranks among my favorite shows.

Once-and-gone, that show was a bit of an anomaly. Fated to grow up, and grimly recognizing the diminishing returns, professional and personal, of pure fury, Costello eased up in the decades since unleashing This Year’s Model, a muting that cast the ferocious material he wrote and performed in the late 1970s in sharp relief. Much of his work from that period feels more alive to me than what he’s cut since the mid 1980s. Such white-hot intensity couldn’t have lasted—it’s a physics problem—yet everyday I’m grateful that it lasted for as long as it did.

See also:

Fantastic. I'd gladly take "Big Tears" over “Living In Paradise” on TYM, but "Hand In Hand" and "You Belong to Me" are essential.

Wow! I don't often read music criticism, but this is so precisely and well rendered. Sidebar: Jack Endino--who'd go on to record and produce Nirvana's "Bleach" LP, among many others, saw EC and The Attractions' first Seattle show in 1978 and told me, as to their savagery as a live band: "They ripped people's faces off."