Here to spread the good word

Joel Gion's memoir recalls transience, speed, and the far superior drug, music

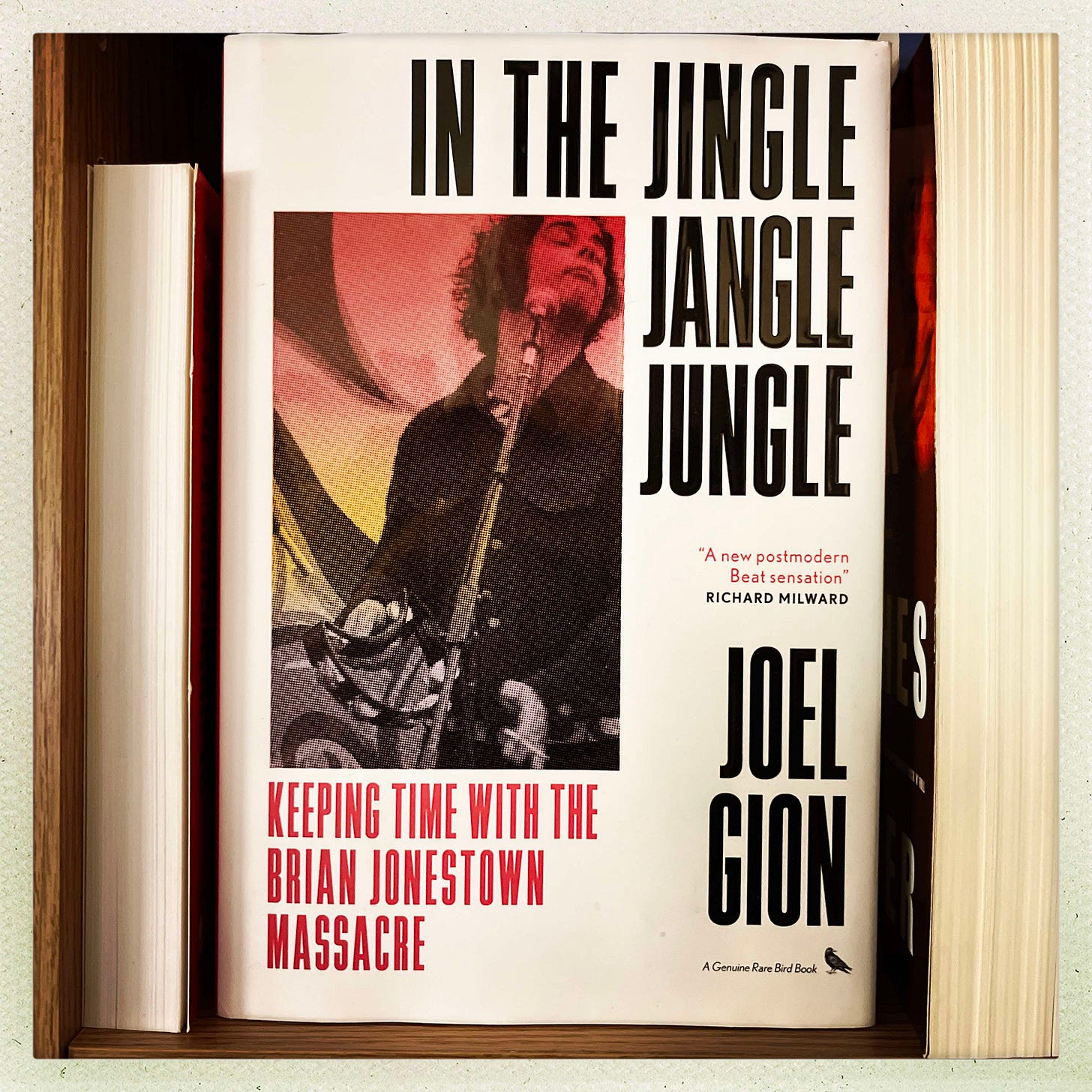

Joel Gion was born in 1970, “the year that because of math killed ‘the 60s’.” So begins the first chapter in Gion’s knockabout memoir In The Jingle Jangle Jungle: Keeping Time with the Brian Jonestown Massacre.

Moments later, we learn that his mother attended an Ike and Tina Turner concert in the late stages of her pregnancy with Gion. Several pages on, he remarks that the first Brian Jonestown Massacre flier he saw, before he was a member of the band, read “TAKE ACID NOW.” An obsession with the spirit of 1960s style and culture, with music, and with mind-altering drugs drives Gion’s memoir, an account of his time in the 1990s as a percussionist in Anton Newcombe’s psychedelic collective of musicians.

Earlier this year, Gion, who left BJM in the 00’s but has since rejoined as an occasional touring member, remarked to James Balmont at inews that Newcombe’s “going to be annoyed when he reads [the memoir],” but that “I have to tell the truth,” adding, “You can’t be a memoir writer and not tell your life in a truthful way.” Absolutely—but Gion has little to worry about. Those expecting a version of the Newcombe who melted down in spectacular ways in the infamous 2004 documentary Dig!, the making of which is chronicled in the memoir, will instead encounter a committed, resilient band leader. Throughout, Gion writes about Newcombe with genuine, deep affection, if at times from a guarded point-of-view, curious as to when Newcombe might erupt or change course all over again. “There is an indescribable natural aura about [Newcombe], a drugless zen of the kind that is up to the observer to find, because he himself seems to be unconscious of it,” Gion writes. Elsewhere, Gion calls Newcombe “in many ways one of the last of the real deals.”

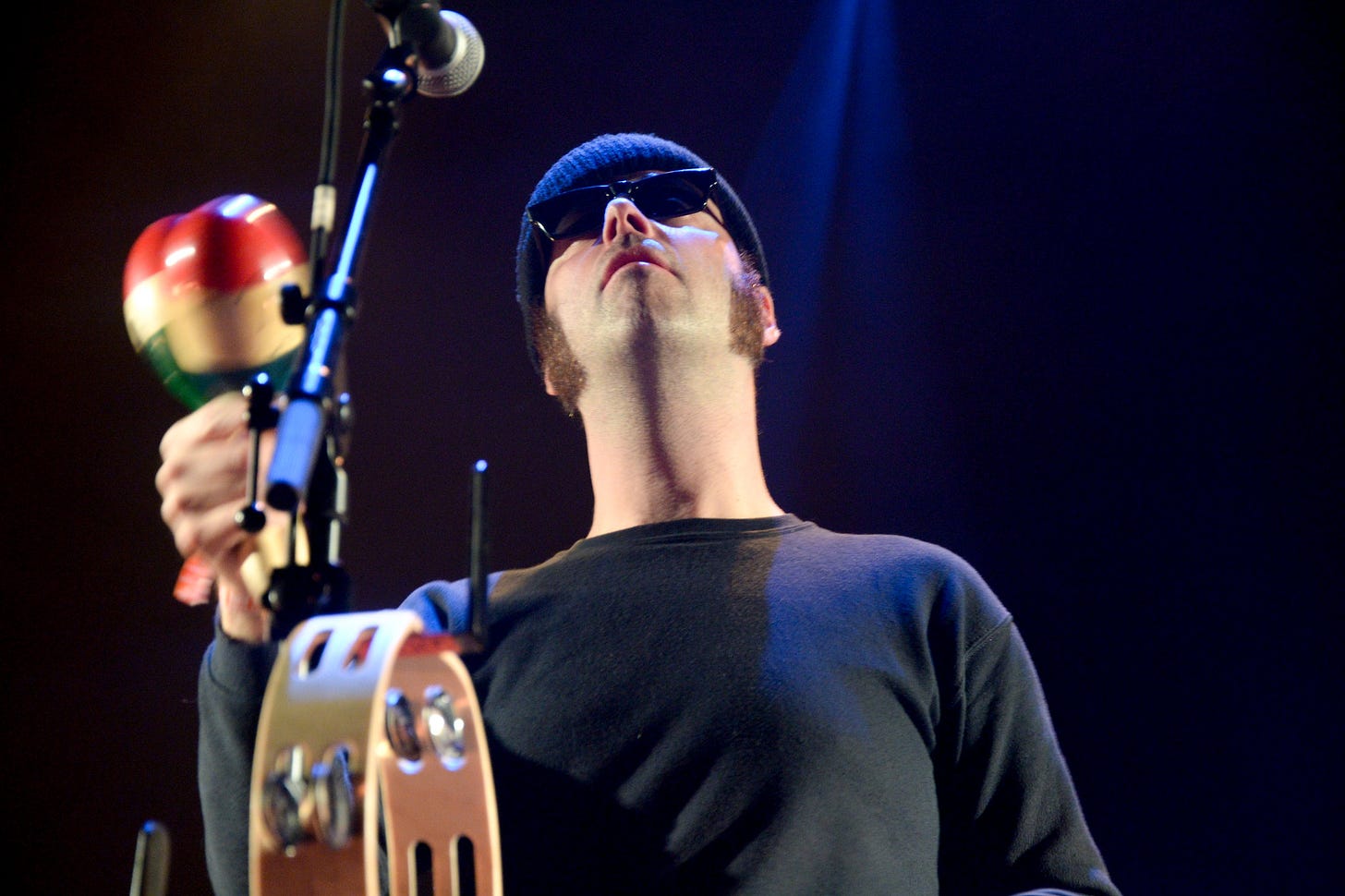

If you’ve seen the Brian Jonestown Massacre live with Gion on percussion—I caught a terrific show last year at The Vic in Chicago—you know his stage demeanor. He’s un-showy, yet crucial. The eye of the storm. Somehow within and without. Those qualities inform his writing, too. Gion acknowledges that he was self-consciously “on” for many of the scenes in Dig!, when he wasn’t blitzed out of his skull. He is genuinely hilarious in the documentary—playful, impish, ironic, dripping with satiric takes in clownish 60s hipster mode. Happily, he’s pretty damn funny on the page, too. His droll observations of chaos and dissolution, much of the disaster self-created, are often hilarious, at their best revealing the stamina and grit it takes to embrace an us-against-them, bohemian, at-times-desperate rocker lifestyle with years of couch-surfing, sink spit baths, and brutal hangovers, when drug-dealing is often the only means of income and when DEA undercover surveillance is not uncommon.

The book moves episodically, and some of the best chapters work as stand-alone set pieces: as when a paranoid Gion is tasked with dealing with a roommate’s mountain-sized stack of parking tickets at a forbidding San Fransisco police station; when he arrives late and hungover to work at Reckless Records and hallucinates demons and ghouls at every corner, only to remember that it’s Halloween (spoiler alert: he’s fired on the spot); when he and his fellow band members are hooted at and Yeah, baby’d! by denizens at a Los Angeles mall because they look like the cast of Austin Powers; when Gion, after a meltdown and with few options, returns to the home he’s sharing with Newcombe and Newcombe’s fiancée imagining the Rolling Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” playing during the sentimental scene, but because he’s fated to play out his threadbare life as an indie film, he can’t afford the rights to the song. And there’s a priceless story involving perhaps the world’s most inept fake ID.

Dry one-liners abound, as well. But Gion’s at his best as a memoirist when he recognizes the thematic value of things. He recalls a Big Wheel race he participated in as a kid where he took a turn at high-speed (well, Big Wheel speed) while every other kid sensibly slowed down; Gion wiped out bad, the consequences of reckless living embedded early (if not always heeded). He pays smart attention to his sorry boots: they’re two sizes too small, and at one point a heel comes off so he’s forced to hobble about town (and, presumably, the stage), a graphic metaphor for a fashion-conscious yet cash-strapped artist who’s forced to sacrifice comfort for style. (Sartorially obsessed, Gion gives his readers a running account, down to the stitch, of his and his bandmates’ 60s’ inspired clothes—and their haircuts.) A generous manager finally gives Gion the money to buy a legit pair of Beatles boots to replace his wounded footwear. They’re not very comfortable, but that’s the point.

Music pulses potently throughout In The Jingle Jangle Jungle, whether it’s spinning on turntables and CD players or created by enchanted bands (there are run-ins with the Dandy Warhols, as well as Oasis, Primal Scream, and other trending groups of the era, and the late, great Greg Shaw of BOMP Records makes a few cameos). Gion’s clearly surrendered to the power that music wields over him, and he writes evocatively about how, while listening to it and playing, music can lift and redeem, yet when one’s vulnerable and exhausted, it can devastate. In one charming passage, he recalls how as a kid he used Beatles songs to internally soundtrack his various crushes on various schoolgirls. (“Michelle of course was ‘Michelle’, Jennifer became the subject of ‘And I Love Her’, that is until she got tired of my staring and told me to drop dead. Then she was switched over to ‘Yesterday.”) Early on, he testifies to his own band’s brand of magic, with which he remains enthralled (“We are here to spread the good word and you either get it or you don’t”), and to the songwriting/recording/performing trinity as a kind of stimulant in and of itself. He writes: “Recording sessions were one space where I didn’t care about doing drugs. They weren’t needed here.”

Watching the music being created was a far superior drug and anyway, while jacked-up enthusiasm was welcome out in the streets, in the recording studio environment it could easily become simple intoxicated babble getting in the way.

In the extraordinary chapter “Heaven Can Wait,” Gion describes an evening in the band’s Los Angeles home when Newcombe played “I’ve Been Waiting,” a song the musicians has just tracked, throughout the house as a kind of “victory dance.” Then he played it again. And again. And again. And again. Gion, trying to sleep in his room, is forced to listen to the track over sixty times as the late night gives way to the early hours which give way to dawn. At each play, Gion, fighting mania, enters the song through a new portal, wrestling with and interpreting the lyrics, floating on mad waves of the song’s repetitions. Each paragraph in the passage begins with the same twenty-two words, graphically evoking the obsessive, ceaseless night.

Gion finally gains fitful sleep at the sun rises and a clueless—or is it cruel?—Newcombe plays the song for the final time, then commences a new recording session, as if nothing curious had happened. The tour de force chapter dramatizes Newcombe’s mania for perfection and his fascination with creating sounds, but also his intense self-preoccupation and lack of concern for others’ feelings (or their mental states). I can’t hear the song the same after reading it.

Alcohol and drugs also course through the memoir, ingested by the author and his bandmates in herculean, increasingly reckless amounts. Meth is Gion’s stimulant of choice. Early on in the book, Gion praises the “transformative powers” of speed: the drug allowed him to transcend his native introversion and to dash electrically and ecstatically through his ideas. Yet for Gion, the quest for oblivion often seemed as urgent as the quest to be a part of a music-making and -playing, creative collective.

On the front cover of In The Jingle Jangle Jungle, the English novelist Richard Milward enthuses that Gion is a “new postmodern Beat sensation.” At first, I balked at the praise. Yet as I read more and more of Gion’s descent into drug use and his struggles to keep afloat emotionally and financially as a destitute, often homeless cult musician, the phrase “dirty grace” popped into my mind: Jack Kerouac’s description of Neal Cassady in On the Road. And, as in a transparency, an incident in Gion’s life recalled a like incident in Kerouac’s.

Late in On the Road, Kerouac recounts a humiliating episode in which he was “the star in one of the filthiest dramas of all time.” During one long night at the Imperial Café in Boston, he’d gotten blind drunk on dozens of beers. He hit the mens room, where he coiled himself around the toilet bowl and passed out. “During the night,” he wrote, “at least a hundred seamen and assorted civilians came in and cast their sentient debouchments on me till I was unrecognizably caked.” His takeaway? “What difference does it make after all?—anonymity in the world of men is better than fame in heaven, for what’s heaven? what’s earth? All in the mind.”

Gion hits a similar low point, though luckily his isn’t quite so debauched. He admits to a “rock bottom” dumpster dive for food behind a Burger King one day in rainy, miserable Portland, desperate with hunger after having not eaten for a few days, his “rational awareness” failing to “sanction a way around acknowledging this being the milestone event of me eating out of a garbage dumpster.” (He grimly acknowledges that the occasion was worse even than the night he passed out drunk on the front steps of a church, awoken in the bright morning by a group of startled worshippers.)

Later, he returned home to his squalid rehearsal space/flophouse to use what he and his housemates decorously called the “death punk toilet,” where he inadvertently wiped onto himself a disgusting glop of bodily-fluid filth that had built up on the bowl over many years. Shocked and repulsed, he instinctively lurched away, “but after jogging around the bathroom in a semicircle, I accept I’m just trying to run away from myself,” adding, “This is the moment when squalor officially defeats me.” He cleans up, but the day—a fierce hunger, a soiled, tossed-away sandwich he can’t stomach, the Death Punk Toilet Incident—has obviously stuck.

A music memoir, like any memoir, can suffer from a lack of self-interrogation, the writer substituting a raft of stories, however juicy, for reflection and hard-won insights. I like that Gion included these more extreme moments (and there are others), because they add up to a dimensional portrait of a struggling musician who, by choice, sticks out the rough patches for yet another night of musical redemption. It isn’t pretty, but it’s real.

In The Jingle Jangle Jungle is not without its flaws. At 350 pages, it’s long. A few of the stand-alone chapters don’t land, and when they do, they don’t stick around for long. Gion opts for a conversational tone, which is fun, but sometimes his sentences get tongue-tied or hipster-mannered, betrayed by clumsy syntax. Too many passages end with variations of the phrases “or something” and “whatever,” when I wish he or his editor had pushed a bit further for clarity and insight rather than give in to the stoner’s shoulder shrug. The drunk-blind and speed-blurred nights and the numerous band fights and member defections begin to dull after a while, though Gion has mastered an impressively diverse number of ways to describe a hangover.

The memoir’s strongest when Gion wrestles, clear-eyed, with the fraught circumstances he’s (mostly) chosen for himself. The epiphanies he reaches near the book’s end feel genuine, the perspective of a refreshed man. He defends his extreme lifestyle as a means to an end, requiring “both reward and hardship and one can’t exist without the other.” The moral: you can’t moan because you’re not having fun all of the time. “The big stuff doesn’t work that way. The small stuff does.” At the end of the book, revived by the surprising success of Dig! and the renewed attention, Gion writes, “no matter how bad things get, they will always eventually get good again,” adding, “You will weather whatever bs storm the fucker gods can make. Things will come around right again, and I know all this because it just happened.”

Here’s Gion reading at City Lights Bookstore in San Fransisco, and an interview from 2011 that puts the lie to the notion that tambourine players don’t seriously know their stuff.

Photo: “Joel Gion, Brian Jonestown Massacre, live at TINALS, Paloma, Nîmes, France, 29th May, 2014” by Pierre Priot via Flickr

Having been a fan of theirs since 'Their Satanic Majesties Second Request,' I had the incredible opportunity in 2006 to design a poster for BJM and was also invited to tag along on their UK, Ireland, and European tour to sell it (I have a good photo of myself and Joel backstage in Dublin or someplace in the UK). I have my own stories about the band, both good and bad. I have seen them many, many, MANY times over the years - some extraordinary shows and others quite awful where I had to walk out as I was so disgusted by the behavior both said and done. This past October, I saw them for what will be my last time as it descended into such ugliness that I just don't need in my life, nor do I need to pay to watch a rock & roll version of the Jerry Springer show or support somebody's mental health breakdowns. I am also less interested in Anton's latest music, which continuously sounds the same. That said, I love all of their early albums - especially from 'Methodrone' up to 'And This Is Our Music' and various bits and pieces that come later ('Days Weeks Moths' is the last really incredible song I think he wrote, but that's just my opinion) and have great memories of the ride while it lasted.

I saw that Joel had written a book, and I'm curious to read it. I'm also curious to hear his version of some of the antics. With all due respect to Joel and the others, they often do nothing when Anton is in meltdown mode, which in the last gig I saw came across as very complicit and almost accepting of toxic behavior, which I can no longer support.

I will eventually get a piece written about my 2006 UK/European tales on the road with BJM.