Green Day, high on a low life

Despite the effervescent surface and snappy sounds, darkness pulses underneath

In their book Teenage Confidential, Michael Barson and Steven Heller write that “Good and evil make themselves evident in real life not as absolutes, but as gradations along a virtually infinite continuum. The American mass media, however, has always operated most comfortably when presenting clearly etched polarities to its consumers."

So it has always been with the teenager in American pop culture. There are good teenagers and bad teenagers, and being just a little bit bad is rather like being just a little bit pregnant—in America, you are either pure a newfallen snow or you carry an indelible taint.

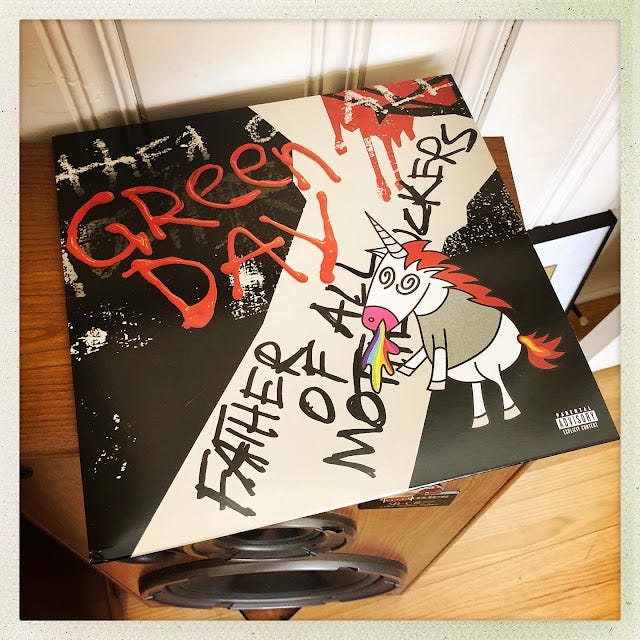

It's obvious which end of the spectrum Billie Joe Armstrong's been singing to since Green Day formed in the late 1980s. The vast majority of his songs chronicle, and are valentines to, the fucked-up, marginalized, dislocated teenagers in all of us. With their new album Father Of All Motherfuckers, Green Day sings again to that disaffected group, but also capture their collective heartbeat in the amped-up, hook-y, riff-y, delirious fizz of the album's sound, part Glam, part dance club, part pop, part speed.

The rock and roll on this album streaks by in a blur—it's over in under a half hour—and so feels like a single night of fun, compressed, mythic, high on sensation with ideas an afterthought, over before it starts. The album's surface effects—processed vocals, synthy handclaps, tinny drums, bright falsettos, keyboard squeaks, a sample of Joan Jett's "Do You Wanna Touch Me" in "Oh Yeah!"—twinkle and clink like glasses on a bar top, but the loud guitars and urgent, anthemic choruses throughout remind you that this is a rock and roll record. Green Day wanted to make an album for you to dance to first, think about later. I don't know about you, but that came just in time for me. overburdened by shitty news about shitty men and women behaving like entitled kids and ruthless bullies, news generally ignored by the band here, in favor of a vibe that says, Hop in the car, we're heading out to the 'burbs for a house party where everybody's a star. Don't look at the newsfeed until the morning.

Armstrong's influences are varied. A couple of the tunes ("Fire, Ready, Aim," "Take The Money And Crawl") sound like he grabbed a guitar after seeing the Hives live or revisiting that band's epic The Black And White Album, and cheers to that—the choruses and sharp riffs ring in the ear like the best of Sweden's finest. Armstrong led the record's hype with the breathless announcement that the songs reflect "The New! soul, Motown, glam and manic anthemic. Punks, freaks and punishers!" Though the album's a clarion call to the dance floor, any mid-60s Motown vibe is buried underneath, surfacing in subtle, syncopated lead-backing vocal arrangements, especially affectingly in the chorus to the otherwise downbeat "Graffitia."

There are other surprising musical nods: I hear the pop gallop of Katrina and The Waves' "Walking On Sunshine" (itself channeling the Supremes) in the frothy yet desperate "Meet Me On The Roof" and the melody in "I Was A Teenage Teenager" suggests the joyfully ascending line in Dexy's Midnight Runners' "Come On Eileen." (Perhaps I hear that reference because Dexys and company scored my mid-teen years.) In the aforementioned "Graffitia," the line "Are we the last (long) forgotten" calls to mind the rousing "Never To Be Forgotten" by Bobby Fuller Four. The Father Of All Motherfuckers cover samples the hand grenade imagery of the artwork for American Idiot, and in the great "Sugar Youth" Armstrong sings the line "I got a feeling and it's dangerous" to the same lyrics, cadence, and melody in American Idiot's "She's A Rebel"—less an unoriginal cop of his past than a recognition that he struck a chord the first time around, and a decade and a half later the chord is still sounding.

Despite the effervescent surface and snappy sounds of Father Of All Motherfuckers, darkness pulses underneath; the album feels light and purposeless, but it isn't. Armstrong can't help but see hopelessness and jadedness around him. (One of the more affecting lines on the album comes in the form of a question that poses a paradox: how high is your low gonna get?) The characters in his songs—half autobiographical stand-in, half face in the crowd—are always a despondent step away from oblivion and carelessness, high school losers who "will never, ever, ever fuck the prom queen."

Armstrong still possesses a direct line to the feeling of the chaos of being sixteen; the album's best song, "I Was A Teenage Teenager," begins with a simple declaration against a plaintive, pre-Beatles melody— "I don't want to freak you out but I cannot lie"—and then to a simple but chilling question—"So who is holding the drugs?" The moment arrives as the album's first half ends, and the song's the album's hinge, a mid-paced, catch-your-breath tale of a a young kid, or an adult who can't shake lose, or who's chasing, the promises of youth, "full of piss and vinegar," "an alien visitor" whose life's "a mess" and who thinks that "school is just for suckers." That kid is poised at the door between a party of sweaty good times where we forget the world for a few hours and dance, and a dark room of despair and ennui and possible self-destruction. The song doesn't tell where they go, what direction they choose, but the choice is graphic. So it always is with the teenager.

For the half hour that Father Of All Motherfuckers lasts—that's shorter than your favorite sitcom—Green Day turns it up and in their eight-notes and downstrokes and handclaps and singalong choruses, on fast songs and slow ones, lets the party lights blind us. We'll regain our vision soon enough. Then it's time to listen to the album again.