How much time will it take

As the 1970s dawned the great Edwin Starr got to the heart of wanting and waiting

I was hurrying, having realized nearly too late that I had to dash to the opposite side of town to grab something before lunch and afternoon classes. Irritated, I hopped into my car and, in too much of a rush to select a playlist on my phone, pressed Shuffle: always a gamble. How many times have I impatiently cycled through tens of thousands of songs, pressing next next next when not in the mood for this song or that artist. I’ve wasted a lot of time—opportunities for surprises, discoveries, the crust of my expectations blown away—while searching. Without that luxury (or is it prison) I’m at the whims of the Gods of Random.

It only took three or so minutes to get where I was going. Unbidden, Edwin Starr’s “My Sweet Lord” led the way. I had a choice. (Press Next.) But something in the opening moments of the song restrained me. I was surprised and then pleased that a song about waiting and longing had come on as I was trying to beat the clock. The stately piano chords and suspensions that usher in Starr’s version quietly insisted that I stay with them; the funky, vibrato-drenched keys in the left channel that arrive next, of their era, sound at first as if they’re interfering in the proceedings—heavy-lidded juvees lounging and goofing off in the back pew with an air of danger—but then they settle in and find their place, though it’s a shaky detente. (They blow a raspberry a minute and half into the song.) The Funk Brothers hard at work. Who’s playing on “My Sweet Lord”? Regrettably it’s tough to know precisely, given the notorious curtain of anonymity that Motown drew over its factory workers. Starr enters on a gentle layer of electric bass and acoustic guitar, singing “Oh, happy day,” after Edwin Hawkins, while backing singers from Total Concept Unlimited (who metamorphosed into Magic Wand and then the popular Rose Royce) chant “sweet, sweet lord.” The thing sounds as if it’s coming at you through mist.

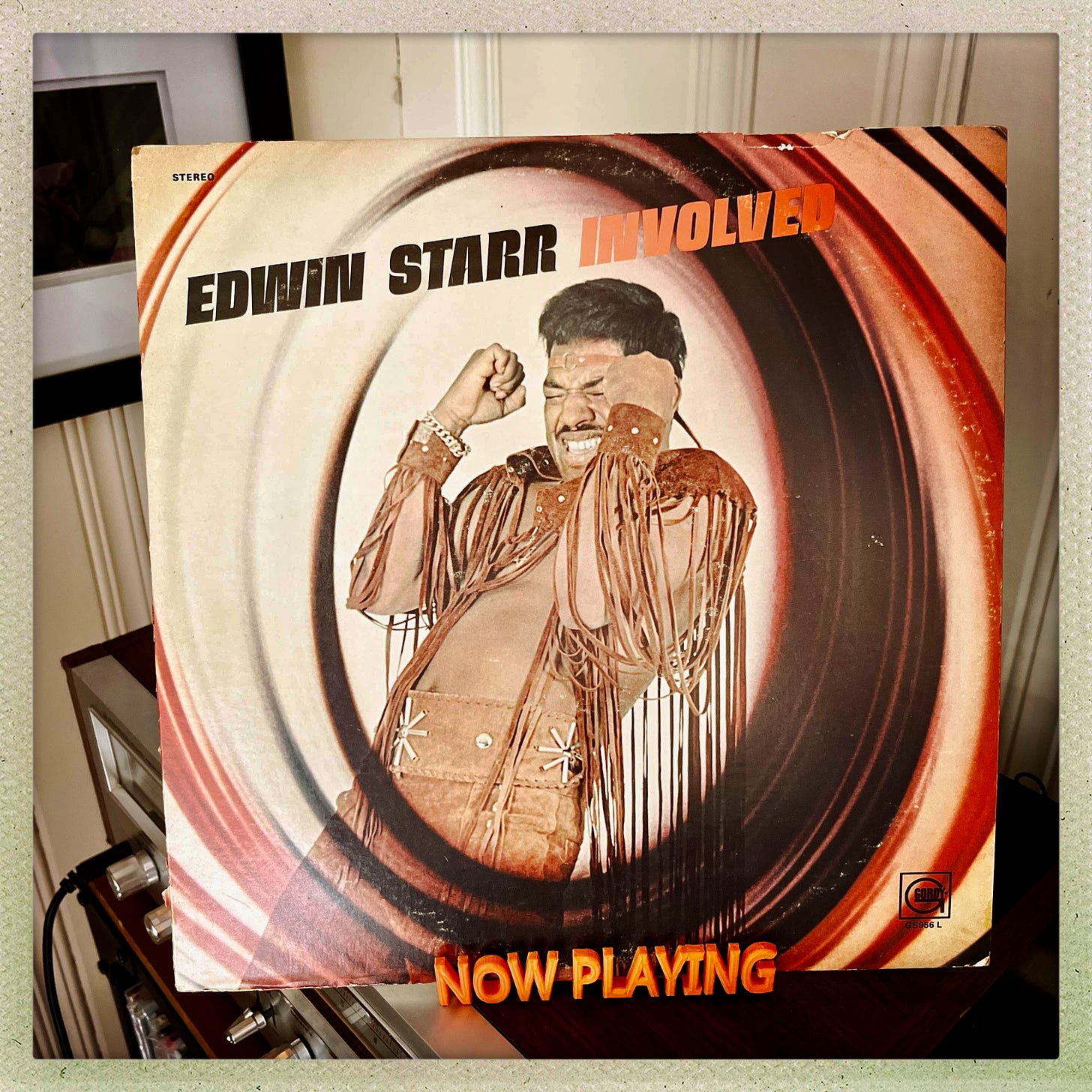

If you’re reading this without having ever heard Starr’s cover, you might be imagining something close to George Harrison’s original, released a few months before Starr’s take, with its ecstatic, hymn-like grandeur and mythic communal rites. But Starr takes the song down a quieter path. (His version closed out his album Involved, released in 1971.) There’s one guitar, not a half dozen; there are a couple of women testifying with Starr, not a massed choir. Where Harrison genially charges up the mountain, beatific, Starr’s reflective under a tree. Or in an alley. Rightly famed for his enormous, commanding voice, Starr moves between ballad understatement and Gospel ferocity—the origins of the dilemma he’s sing about, waiting and then trusting and then demanding. Harrison’s lovely melody and sweet changes remain, but Starr sings as if he’s addressing a more secular desire. “I really want to see you,” he implores, “I really want to be with you….but it takes so long.” He could be a kid in an army barracks, writing to his girl back home, or a suitor beneath a shut window. Listen with half an ear and it sounds as if the women behind him are singing “sweet, sweet love” and that we’re in a bedroom. All of this works beautifully in the arrangement, the pleas carnal but no less spiritual.

Things pick up as a gently-struck snare rim in four-four time enters, and two and a half minutes in Starr’s vocal’s muscled forth with the full band—but Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” is in Starr’s hard-won psalm a simple room with a wooden chair, a modest bed, a window. All he needs, really—all he has—is his voice, and he lets it move him from quiet contemplation to melismatic fervor. He’s essentially alone in the room of his sweet pain. Harrison’s massively, gorgeously sung Sanskrit and Krishna mantras—Hare Hare, Gurur Brahma, Gurur Vishnu, and the rest, which Harrison slyly dropped in so that we’d all be singing mantras without realizing it, blissful in inter-faith harmony—are nowhere to be found in Starr’s room. He doesn’t need them? Or they don’t speak to him, for him? He floats on the song’s gentle, moving changes out the window as the songs fades.

Somehow, Starr’s version feels less resolved than Harrison’s. Same words, mostly, same melody, same hunger for divine connection, yet Harrison’s communal chorus—an anthem for the hip young quasi-religious sect—feels as if in the very celebrating of desire we’ve solved that desire, or have sung it into a kind of sweetness that forgives its very real hungers. Starr? He sounds as frustrated at the song’s fade as he does as its opening.

I wrote a few months back about my neutrality toward sacred music. I was utterly galvanized by Starr’s performance as I drove, and in a kind of cosmic timing, “My Sweet Lord” ended as I pulled into the parking lot of where I needed to be and was so annoyed about moments earlier. To write that I was changed or saved during those two hundred and forty-eight seconds would be glib; I was first taken by surprise, then deeply moved over the course of the song, astonished at how it jumped me and wouldn’t let go. I surrendered, certainly. If my pettiness and impatience were absorbed into something grander, into something less punily personal, then my time was well served.

“…but finally, I suppose, the most difficult (and most rewarding) thing in my life has been the fact that I was born a Negro and was forced, therefore, to effect some kind of truce with this reality. (Truce, by the way, is the best one can hope for.)”

So wrote James Baldwin in his “Autobiographical Notes” in Notes of a Native Son, published in the middle of the last century, lines that have never left my head. Baldwin’s dilemma—the perpetual motion machine of difficulty and reward, truce and eruption—hums beneath nearly everything he’d write.

Starr’s ensnared—by devotion, by time and history—and reaches a truce in song that lasts for several minutes, or for an album or a show. He moves between patience and fury, and the space between those two is utterly enormous, possibly infinite; anyway, it can take a lifetime to navigate it while the poles move ever further apart. A truce, by nature, never lasts, the obvious yet still devastating discovery at the heart of these two songs and Starr’s performances. Reality in a song can meet the reality outside of it and find strangers gazing back.

Most bio sketches will observe that Starr never received the level of fame and recognition that he was due; it’s true that, although everyone knows “War,” not everyone knows the name of the person who sings it—he’s not on par with the likes of Smokey Robinson or Diana Ross or Marvin Gaye in Tamla/Motown iconography. But his voice and interpretive skills were among the strongest and most enduring that the label unleashed. A ferocious singer with controlled, extraordinary dynamics, Starr possessed vocals that were frightening in their righteousness and power. He died in 2003.

For a long time I’ve been obsessed with the track “Time” from War & Peace, released in 1970 (co-written by Starr with Richard “Popcorn” Wylie and Wade Marcus, it was issued as a single as the follow-up to “War.” Quite the ask.). Baldwin’s lines ghost the words that Starr’s singing in both “My Sweet Lord” and in “Time.” Back home after being laid out by the marvel of the Harrison cover I listened again to “Time,” which now sounded to me like the angry, impulsive flip-side to the balm of patience and agony of waiting. The arrangement, again muscled into shape by the peerless Funk Brothers, is a sonic illustration of form nearly conquering content. The song begins with a chiming, and charming, tick-tock over a metronomic hi-hat; horns arrive in the fifth measure playing descending notes until Starr enters, looks around with disgust, and commands, “Well, well, well, well well well.” That clock up on the wall is destroyed, pummeled by a driving, headlong, full band rush into the first verse, though its looming and stubborn presence is never absent from the song.

Oh let me tell ya. An emboldened Starr refers to the time of the second-hand moving implacably on the clock face, sure—

Time is the one thing everybody feels

It just expires with no regards to years

but also to the time of eras and moods and movements:

They say time can bring about a change—listen!

But I ain’t see a doggone thing

“That’s what they tell me: It takes time,” Starr laments, his patience growing thinner with each verse. The problem? ‘“It’s in the answer,’ that’s what people say / But it looks like peace is getting further away.”

“Together we stand, and divided we fall / But we are still divided by that unseen wall” is among the most powerful lyric couplets of the late ‘60s/early ‘70s, a devastating comment on both the potential that time offers and the speed at which time is wasted, the unseen wall created by the implacable spin of the earth as well the bigotry, selfishness, and short-sightedness of the folks spinning upon it.

“Time” is a seriously pissed-off song, Starr’s ferocity echoed in the relentless tambourine and fiery backing vocals, clamoring for their own attention in the riot. Starr reaches for some measure of optimism in the last verse, but it burns to a crisp, really, under the white-hot heat of his performance. Like so many great songs, the from can’t bear the content, which consumes it with its own urgency. (“How much time will it take”" the song pleads.) It’s amazing that the musicians cut something this combustible without burning down the studio. A positively stirring recording, it will stand as one of the most powerful songs of its era. We’ll never solve time, but Starr offers a truce of sorts here.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that War & Peace also includes the song to turn up when you’ve gotten the bitterness out of your system and you’re ready to party. Starr’s streak through Little Willie John’s “All Around The World,” in an absurdly fun and funky arrangement that the Fleshtones taught me decades ago via their riotous 1981 cover, is the perfect antidote to the grim recognitions in “Time.”

Fuck the clock on the wall, tomorrow will never come as long as the joint’s rocking. And God can wait until Sunday.

“167th St. Station. James Baldwin Mural. New York, NY.” by Kathy Drasky via Flickr (image cropped)

Thank you for this wonderful tribute to an extremely underrated soul man.

He could sing the phone book and it would be swinging. Really enjoyed this piece and listening to three songs I hadn't heard before. What a talent and a great guy.