In 1968. the Isley Brothers—O’Kelly, Rudolph, and Ronald—left Motown Records for their own, revived, T-Neck label, eager to capitalize on the success of their 1966 hit “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You)” and to gain some measure of artistic control over their work. They scored big with their first release: “It's Your Thing” was a number one hit on Billboard's R&B Chart, and reached the number two spot on the Hot 100, selling nearly two million copies. The follow-up, “I Turned You On,” also performed well. But their next release gave the fullest indication that the brothers were now firmly behind the wheel and steering the vehicle down some wild, multicolored alleys.

In the liner notes on the back cover of the Isley Brothers’ boldly-titled album It’s Our Thing (1969), O’Kelly Isley proclaims, “We want to do our own thing on records. We feel that we have a sound and a thing that is new, and we want to do it all on our own.” He added,

When we were with Motown we learned an awful lot. Like things about production, arranging, and even more about writing. We always wrote songs, but when we went to Motown we stopped writing. I mean they have such great writers over there, why should we try and beat them?

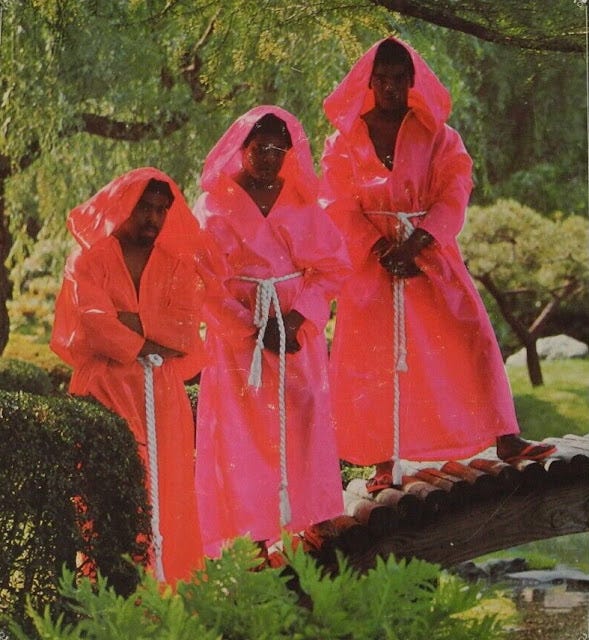

Rudy continued, “Groups like the Beatles and the Stones, they do what they want to. What they feel is important to them. Through a lot of their work entirely new aspects of music have opened up. These areas can accommodate that many more artists so it has a way of broadening the outlook of the music scene.” Ronald breaks the news: “We have a group called The Brothers 3. They’re what they call ‘psychedelic soul,’ and we expect great things from them.”

Ed Ochs pulled aside the curtain in a small item in his “Soul Sauce” column in the June 7, 1969 issue of Billboard:

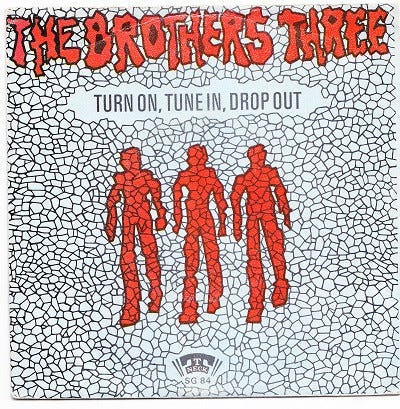

Yet I don't think anyone, casual Isley fans or die-hards, were quite ready for “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out.” Recorded on January 3, 1969 at Town Sound Studios in Englewood, New Jersey, the tune’s a sprawling, unruly, trippy statement-of-purpose, utterly of-its-era and yet powerfully, movingly transcendent. Occupying both sides of the 45, “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out,” though mid-paced, is manic, nearly overheated, with excitable, out-of-tune horns, distorted, fuzz-laden guitar leads so sharp they could cut, power chords, dreamy backing vocals they feel imported from another, far more safe, song, and an unhinged lead vocal that threatens to take the whole thing down. The arrangement’s brutally simple, and the brothers play loud—ever wanted to hear Blue Cheer backing the Isley’s? I didn’t know I did, either. The raw guitars and bass move stubbornly among a few chords, so closely that they evoke a drone of sorts which powers the song forward like some colossal figure taking purposeful, pounding strides that land with righteous thuds. The image at the top of this piece is of the picture sleeve of the French pressing of the single—whoever was in charge in the design department over there felt those reverberations, also. Yet another contact high.

The lyrics match the music’s primal directness:

I’m so tried of running this race

I’m so tired of doors slamming in my face

It ain’t my dream, it ain’t my game, it ain’t my thing

I’m so tried of trying to be a millionaire

I don’t seem to be getting anywhere

Just like the birds I wanna, I gotta be free

Free as the birds and the bees

Relax my mind, I wanna take my time

I wanna blow my mind

Are you ready for that? the singer asks near the end, directing the question to the Isleys’ fans and to anyone else who might be listening (and feel threatened), from bedrooms to boardrooms. The complaints against capitalism and a miserly society are timeless, yet here they originate from specific cultural places, lousy ones at that: the Isley’s are writing, singing, and performing as Black men looking for a commercial hit with mainstream America while turning up the psychedelic faders to trippy levels, loudly proclaiming their rights to indulge a new way of perceiving everything. They would achieve sustained success and security in their considerable legacy in the following years, but in the summer of ‘69, with deafening reverberations of racist, socio-economic, and cultural shots fired in the air over their heads, felling some of their brothers and sisters, the Isley’s were adrift yet ready, and anxious to course correct.

This song’s pissed-off, the anger expressed directly and clearly in the lyrics finding an unruly spirit in the rocking performance; divorced of social context, the brothers morph into silhouettes. The horns and braying vocal feel inevitable, wildly expressive: how can you bitch about these things, and demand other things, without fearing the loss of control? In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin observed that “The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose.” That the Isley’s maintain control of this careening track is testament to their genius in the studio, of course, but also to their commitment to the song’s righteous yet nervy demands for liberty: sometimes you gotta threaten to turn stuff over, make a thing teeter until it might collapse. The song is not not goofy and over the top, and I suppose that it might be easy to hear it as time- and date-stamped, as a vintage curio of late 1960s ether, steeped in the fashions of the time. But that would miss the point: those dopey “la la la la la”’s in the background sound like ironic anti-fairy tales by the end of the record, the “trip” is a genuine journey, and the lyrics are depressingly relevant more than half a century later.

“Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out” is so graphically expressive, pulsates with so much passion, nutty dark humor, and bold, uncomplicated/complicated desires that it’s a wonder the needle stays on the record when it spins. Play Loud.