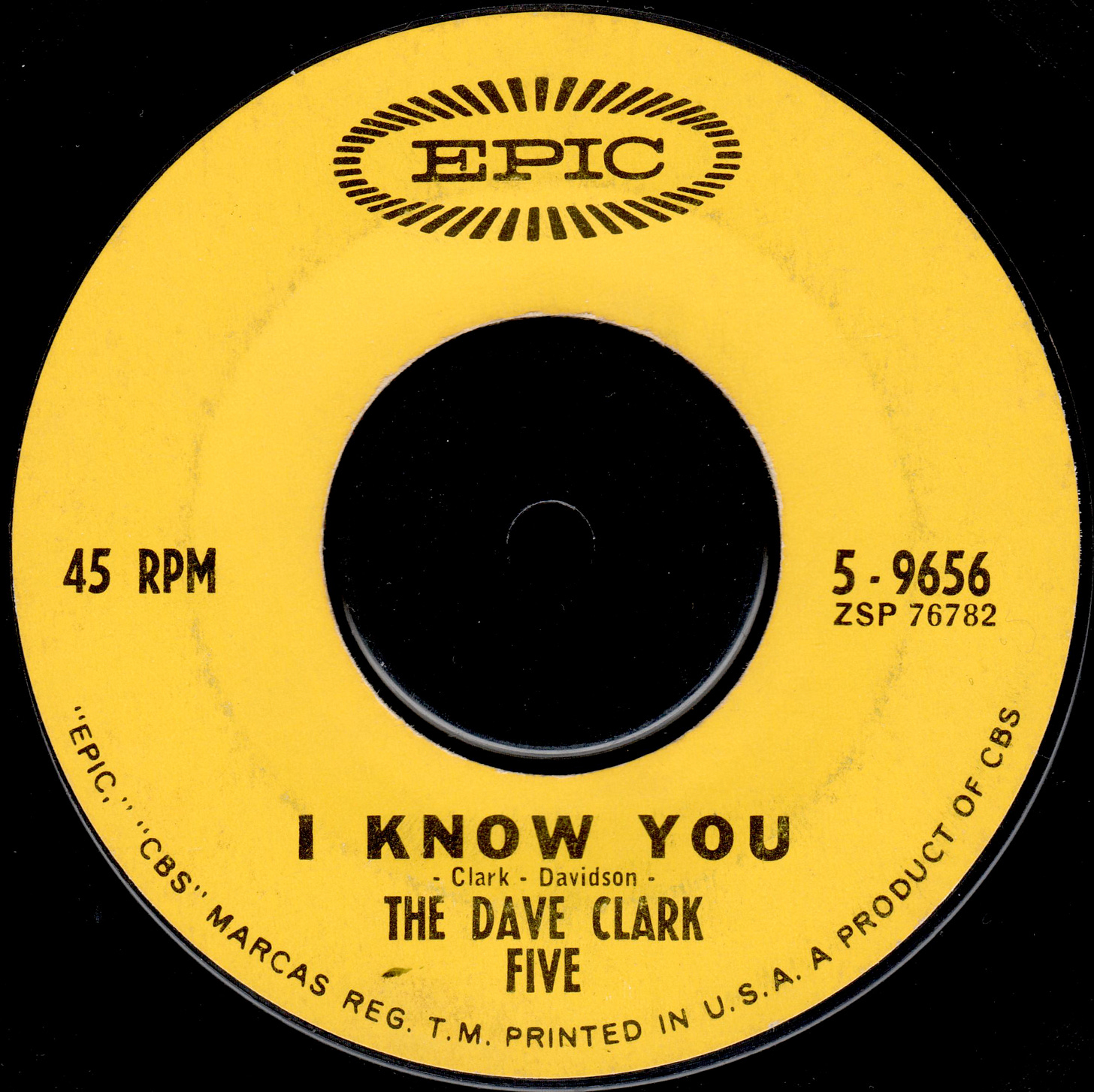

I’m always astounded at how booming Dave Clark Five songs are, especially their early tracks, especially on their 45s. Hell, even their ballads were loud. I pulled out “Glad All Over” the other night, but, as great as that song is, I was struck this time around by the flip side, which I hand’t cranked in a while. “I Know You” makes a lot of noise in its detonated two minutes.

The “Tottenham Sound” was made for the 45, a format that, in short, is hospitable to volume with its wider grooves and faster rotation. As explained at the essential Classic 45 site, in 1948 RCA engineers via a “precise optimization procedure” determined the speed at which a seven-inch single rotates, “given vinyl groove dimensions and certain assumptions about bandwidth and tolerable distortion.” Their figures revealed that “the optimum use of a disc record of constant rotational speed occurs when the innermost recorded diameter is half the outermost recorded diameter.” This is why a 7-inch single has a label that’s 3 1/2 inches in diameter. Genius! The 33-1/3 12-inch album format, developed later by Columbia Records, “was a compromise that attempted to fit more music on a single disc, accepting the [sound] limitations.” In order to cram singles and tossed-off tracks onto an LP, “a wide dynamic range or amplitude have to be reduced in level, otherwise they can damage adjacent channel grooves.”

In the case of 45s, the cutting engineer has more available surface area and a greater rotation speed to play with, since he only has one track to worry per side. The higher rotation speed of 45 RPM allows for a wider frequency response, and the larger available surface area allows for less compression of any signals with a wide amplitude. Bass is an example of a wide amplitude signal that sounds better on 45. Overtones and high treble are also better.

45s literally move faster than LPs, thus more can be squeezed into the grooves. Essentially: “More bumps and grooves created in pressing a 45 means better audio quality.” And BOOM goes the Dave Clark Five—not to mention so many of those great-sounding records exploding from transistor radios in the 1960s. The sheer wallop of “I Know You” is extraordinary, from the rumbling low end through the aggressive mid-range and chiming high end. Guitarist Lenny Davidson kicks things off with a snarling, dirty riff that wraps around the song, barely containing the grinning mayhem of Clark’s pounding drumming and Rick Huxley’s bass, which positively throbs (especially through headphones), and the toweringly stacked vocals. The song’s so loud—so heavy—that the change at the bridge threatens to topple over the whole thing. Good thing it’s over in only a hundred and twenty seconds.

The Dave Clark Five benefitted mightily from the staff with whom they worked at Lansdowne Studios, in London, where they demoed and recorded their key early material. “Built in 1958 by producer Dennis Preston and engineers Joe Meek and Adrian Kerridge, the studio was housed in Lansdowne House, a former artist apartment complex constructed in 1904 in the Holland Park section of London,” Matt Hurwtiz wrote at Mix. Kerridge had helped the legendary Meek build the studio in the late-50s. I was unaware of the Five/Meek connection, and it makes perfect sense: Meek was obsessed with the possibilities of studio recording and sound engineering, and Kerridge carried the torch. (Don’t look now, but the studio that was rough enough for the Dave Clark Five and the Sex Pistols is now a high-end triplex apartment. Alas.)

Clark loved Kerridge, thought he was “brilliant,” a “master,” and especially dug that Kerridge, after Meek, strove to capture a live sound at Lansdowne. Dave Clark Five shows were legendary in their stomping mania and energy transference between band and crowd, and Clark and his band were eager to in the studio to replicate, or at least catch the vibe of, their shows. “We were basically a live band,” Clark said. “So I believed we should try to get a live sound.” Hurwitz relates a great detail: “Key to the experience of a Dave Clark Five show at the Tottenham [Royal, a concert venue) was a bit of audience participation, typically involving a Clark drum break, getting the audience stomping their feet in time to his playing.”

“I’d actually pay somebody five pounds to go switch all the lights on and off in the ballroom, in time with the stomps,” he says. “That’s what gave Mike and I the idea for ‘Glad All Over,’” whose chorus features a can’t-help-yourself “bomp-bomp” chorus.

Another advantage to working at Lansdowne was the band and Kerridge’s ability to push everything into the red, needles aquiver as the band stomped and roared. Because Clark independently produced his recordings and leased the masters to labels, his band weren’t beholden to a particular studio’s rules and regulations common to the industry. (Think of George Martin and Norman Smith’s early reluctance to get loud at Abbey Road.) “We took it to the limit,” Clark acknowledged. “And if we hadn’t been independent, we wouldn’t have been able to do that. But I just felt you needed to re-create that excitement that you got when you were playing live.” Another great detail that Hurwitz shares is Clark’s alertness to his band going slack over multiple recording takes. “We’d never go more than three takes on a song,” Clark says. “I always believed that if you went through any more than that, it becomes automatic. If we went through three takes and didn’t get it, we would just stop and go down to the pub for a beer, and then come back and try it again.”

That bonkers reverb so familiar on the early Five recordings was attained via two chambers at Lansdowne: “a true reverb chamber, designed and built by Meek and Kerridge, used most typically, and another, which took advantage of the old brick building’s tall stairwell, with mics at each end.”

“We usually used the reverb chamber, but we would occasionally use the stairwell version, for special effect,” Kerridge explains.

“It had a great sound,” Clark notes, “but if a resident came down the stairs while you were using it, you had to start all over.” Adds Kerridge, “It would upset the residents when we’d use it. They used to get angry.”

All of this—needles in the red, a lager-loosened band, pissed-off neighbors—amounted to some great and eternal rock and roll. I loved this so much as a kid because it’s great big fun noise—the singer’s practically throwing a temper tantrum in the bridge. Go ahead and crank this upload of my ancient and lovingly-worn 45. You don’t really have a choice: it'll be loud at any volume.

64-0321-18 - Dave Clark Five (Pop Weekly 2-30) by Bradford Timeline via Flickr

I got their greatest hits CD and you're right about the volume; Clark is practically smashing his drum kit and Mike Smith's lead vocals are quite...unsubtle.

But, still, they were great musicians. Their cover of Chuck Berry's "Reelin' And Rockin'" is absolutely jaw-dropping.