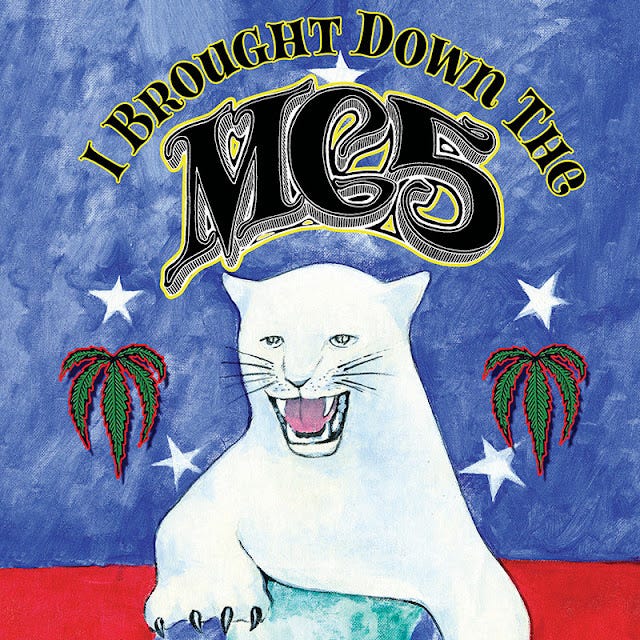

Late in Michael Davis's I Brought Down the MC5, the born-and-bred Motor City musician lands on two phrases that pretty much sum up his story: "confused and content" and "calamity and repair." A little while earlier, he writes that his first thought after having struck his wife in the presence of his young son was I needed more beer—which, inadvertently, could been the subtitle to this book.

I'm not cherry picking moments at the outset to make a churlish point: Davis's personal behavior throughout his story is largely self-centered, and he's unsparing about the reckless, sometimes cruel places his alcoholism and drug abuse brought him. Reading the book gives the impression of hearing a legendary townie a couple bar stools down holding forth appealingly, and as rock memoirs go, many aspects of this book are ideal: Davis is brutally honest throughout, whether he's criticizing former bandmates or his own louche behavior.

He writes vividly about his decades-long alcohol and drug abuse—days lost to benders, shooting up in grimy gas station bathrooms, wrecking cars, arrests, and the rest. His early love of rock and roll (Davis was born in 1943), his first bands, the MC5's formation and their early shows (about which I was startled to learn that they covered the Beatles' "This Boy") and alignment with John Sinclair, international touring burdened with band animosity and bouts of drinking, lightened by rapturous responses from audiences and plenty of free sex with hippies, vexed recording sessions—all are related in detail and with the I was there POV you relish in music memoirs. With the exception of drummer Dennis Thompson, the members of the MC5 come across in Davis's telling as equal parts insecure, arrogant, and aloof, guitarists Wayne Kramer and Fred Smith particularly, their boorish behavior softened with the odd moment of beery or weed-fostered band solidarity. Davis felt estranged from singer Rob Tyner since the early days of the band, and the two never warmed to each other before Tyner's death in 1991.

Inter-band dysfunction is hardly rare, though in Davis's case the unease with his band members seemed to have been a function of his own general feelings of alienation and his difficulty in connecting deeply with other human beings. He hesitantly traces his "lone wolf" identity to his family's lack of warmth and their disinclination to talk about difficult subjects. Davis's parents are portrayed as unconditionally supportive of him, through adolescent drug and alcohol escapades and sketchy marriages up through and beyond his mid-1970s stint in federal prison for drug offenses.

Yet, emotional distance prevailed. "My family was something less than open," Davis writes early in the book. "We just didn't communicate that well. Talking was not our forte; silence was our preferred state, each of us away in our private world of thoughts." Later, home after his stint in prison, he asks: "What was it that kept us from sharing our real feelings? I don't know. After the initial greetings and obvious conversation, it seemed that an impasse always occurred that propelled us off in other directions." When that impasse unsurprisingly manifested in other relationships in Davis's life, he usually responded by bolting, and losing himself in drugs and alcohol, scarring addictive behavior that wore him down physically and spiritually.

Near the end of the book, he arrives at an epiphany of sorts: "I don’t know why, but I've never bothered to worry over the direction of my life ever since well, first departing my parents' protective haven."

Drug addiction, alcoholism, and futile romantic pursuits all marked me as either an emotionally disturbed individual or a damned fool. I was determined to experience everything and refused to be constrained by society, the law, or my own better judgment.

Variations on I don't know pop up all over the book, either as an evasive gestures on Davis's part or as genuine befuddlement. Either way, he often fails to navigate the distance between "emotionally disturbed" and "damn fool"—and the book might've been stronger had he lingered in the nervy implications of that complicated gulf a while longer.

Davis certainly doesn't sidestep his feelings about the MC5's righteous White Panther politics, their hostile, and ostensibly unifying, public front. From the beginning, Davis found the posturing dubious, describing inane press conferences where Kramer parroted Sinclair's politics. "I remember taking Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book into the bathroom one day for reading material. All of our former housemates were always quoting from the book. I read through the first few pages, and that was all it took. It was suddenly apparent that this directive was made for a regiment of ants." He adds dryly, "If you happened to be an ant, here was the plan and you’d better not deviate." Sensitive, intellectually curious, and innately introverted, Davis was sympathetic to the band's Leftist politics, but he recoiled at the hypocrisy: "I didn’t mind us bashing away at the establishment, but I certainly didn't see how we were in line to take it over if it all came crashing down."

Life went on, and day-by-day, our habits became routine. Our rhetoric became more homogenous, decrying the events of the [Vietnam] war and other profound errors of the time. Our voices were loud and our performances were rowdy, challenging the rules of obscenity and decorum.

"But," he adds, "I only wanted to be in a rock and roll band. This crusade to forge a new world seemed ludicrous, a Quixotic lunge at an imaginary adversary."

Davis describes a moment in New York City where the irony between the band's adopted politics and their lifestyle was cast in sharp relief. The MC5 were booked to play a pivotal gig at the Fillmore East, but the show was delayed as the Motherfuckers, a group of radicals who believed that the virtuous band from Detroit had their back, protested loudly, first outside and then during the show. "We came to play music, not politics," Rob Tyner shouted from the stage, unhelpfully. After the raucous performance, members of the Motherfuckers confronted band MC Brother J.C. Crawford on the floor. "Immediately, Wayne entered the fracas with endless explanations, trying to justify our position," Davis writes. "I stood by with not a single idea how to solve the debate. It was a helpless mess. After a while, the theater staff insisted we should leave through the back door, and out into an alley. Once there, the spirited debate resumed."

Looking to my right, I saw the blade of a knife in someone's hand. Two stretch limos idled nearby, sent by the record label to drive us to our hotel. It came down to this: If we got into those limos, we were the Enemy.

The Enemy gladly ducked into the limos and made it safely to their hotels, where their partying continued. The wide interval between the street-savvy Motherfuckers and the luxury vehicles? Not lost on Davis. (Wayne Kramer gives a full, detail-rich account of this night in "The Fillmore Fiasco" chapter in his memoir The Hard Stuff. He and Davis essentially come to the same conclusions.)

Davis writes equally well about rock and roll, especially his band's incendiary version of it. Onstage, he writes, "it was impossible to hear the vocals unless we were playing softly, which rarely happened. Things would get so confused at times that we would look at each other with panic and frustration, trying to get back in sync. I can’t think of a single show that didn’t include some form of musical derailment. Some were momentary, while others were extended lapses into musical chaos. Dennis would become completely unhinged when none of the instruments were playing on the same beat. Yet at times, he was the reason for the fault. Who could hear what was going on?" He wonders if maybe his band's mistakes "were actually a key part of our act, unintended, but nonetheless a part of the show," adding that "the desperation and drama that was created, and the rescue that took place must have had an emotional value that made seeing the MC5 unparalleled. I can’t say, being one who was on the stage."

"If I’d been a fan," he writes elsewhere, "coming to an MC5 show that balanced on a tightrope, pitting the power of law enforcement against the raucous energy of a crowd of hormonal teenagers and psychedelic rabble rousers wearing spangled colors, draping flags over their amplifiers, blasting high energy beats and screaming liberation anthems, then I would have been just as spirited and carried away by the event as any young person could possibly be." Interestingly, he considers the MC5's second single, "Looking At You," and their final album High Time to be the band's high-water marks; he was deeply disappointed at the way Kick Out The Jams turned out, in terms of its sound and its packaging, and, like the whole world it seemed, complained about the lack of ballsy low-end on the band's second album, Back In The USA.

Following his dismissal from the MC5 and his time in jail, Davis took odd jobs as necessary—auto body work, deliveries, landscaping, a meaningful, enriching job at a nature center—to support his drinking and drugging, and his growing family, and he dropped in and out of various art schools, stoking his lifelong love of painting. He carried his chops, if not copious amounts of self-confidence, into several bands, some middling, the most notable being Destroy All Monsters, the artsy, ragtag noise outfit headed for most of its career by Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton with the singer Niagara. (Davis gets a dig in at the wildly dysfunctional band, with which he never jelled, by titling the chapter "Delirious Alcoholic Megalosaurs.") Asheton comes across as unfriendly and self-centered—but then in this book just about everyone does, from ex-band members to ex-wives. This seems to stem not from meanness in Davis's spirit or from paranoia but from his inability to allow himself to become intimate with anyone for extended periods.

Sadly, the joy of making music never seemed to last very long for Davis before it was erased by drink and drugs, replaced by the need to score, find The One woman (she's often recklessly young), or secure hard solitude. Moments of joy would occur: in one of the more charming moments in the book, Davis, while in Detroit on a late-career tour, brings members of a band he's playing with to visit the crumbling facade of the Fortune Records building on Third Avenue. Fan-boy gushing, he asks "an old bum" who's ambling by to take his picture in front of the building. If only Davis had been around to marvel at and to read Billy Miller and Michael Hurtt's loving history of the label, Mind Over Matter: The Myths & Mysteries of Detroit's Fortune Records (for which John Sinclair wrote an Afterword).

I Brought Down the MC5 is an affecting memoir, if a dispiriting read. It reminds me a bit of Ace Frehley's No Regrets, in that each book present a man who lost years to alcohol and drug abuse, and for whom music was always a saving grace, more powerful a lure than intimacies of other kinds. Ace, of course, has survived. Davis died of liver failure in 2012. What's intriguing is what Davis left out of his book; an Epilogue states that, for unknown reasons Davis declined to write about his later strong marriage to Angela Davis, his thriving and recognized art work, his reunion with Kramer and Thompson in DKT/MC5, and his establishment of the Music Is Revolution Foundation, which supports music education programs in public schools. Perhaps he planned on covering those in a second memoir. Sadly we won't get that; instead we have a spirited and unprecedented first act and a muddling, unfocused, and often unhappy second act, the calamity before the repair.