"Most of you won't like this"

Listening to Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music in full for the first time

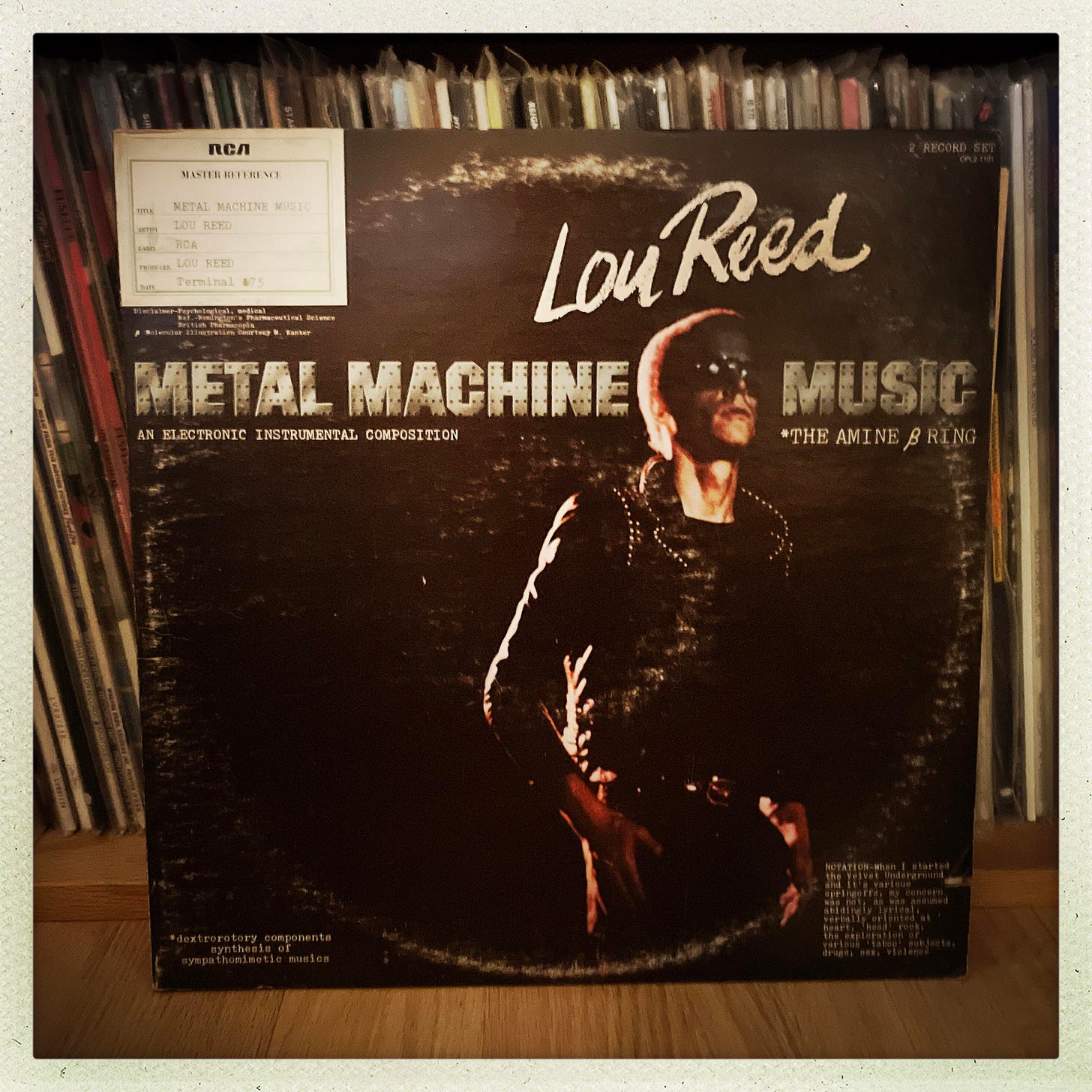

On a bright, breezy morning recently, I put on Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, as you do. I’d tracked down a decently-priced vinyl copy of the infamous double album in good condition, and was eager to listen to the whole thing end-to-end, which I’d never done. Inspired by Lester Bangs revealing that he obsessively played the album in his car on an 8-track—picture Lester cruising down Eighth Avenue—I grooved to the first two sides at the gym, the dark noise in my headphones competing with innocent public spectacle. I jammed the second two sides, loudly, while at home. The window was open, and chain saws were felling a tree down the block. Usually in this situation I’d close the window against the din, but….

If you’re below a certain age, some history: Bangs & Reed were a popular comedy act from the mid-1970s, gadfly and straight man, respectively, though at the times those roles shifted. Bangs worshipped rock and roll, the Velvet Underground, and Reed, and wrote about Reed honestly, cuttingly, adoringly, and skeptically in the pages of Creem, and elsewhere. (Bangs’s best writing has been collected in two essential books, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, edited by Greil Marcus, and Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste, edited John Morthland.) When Reed released Metal Machine Music in the summer of 1975, Bangs was given a top challenge, the kind he relished: he had to figure out if what he was listening to was inspired art or an FU con job. In many ways, Reed and Bangs were a marriage made in heaven, or hell, depending on either’s mood, and a half century later, the release of Metal Machine Music feels fated, an epic confrontation (and possibly, a semi-joke) laid at the feet not only of Reed’s label executives and his fans, but of his most discerning and thoughtful, and, so, valuable critic.

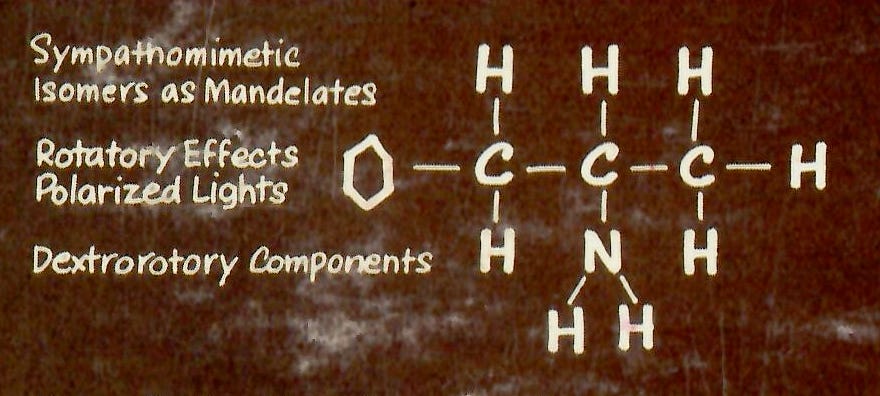

Metal Machine Music is an hour of sublime clamor. Recording alone in his Manhattan loft on a Sony half-inch and Uher and Pioneer quarter-inch tape decks, tethered to and lost inside of headphones, Reed fed his guitar playing through amplifiers and preamps, fuzz box distorters, modulators, speakers, mics, and tremolo units, within the floors and ceilings of treble and bass settings, producing enormous walls of deafening, distorted feedback. On the back of the album, Reed revealed, among other minute specifications, that while assembling his mechanical soundscape he was working within ideas of “Drone cognizance and harmonic possibilities vis a vis Lamont [sic] Young’s Dream Music,” “Rock orientation, melodically disguised, i.e. drag,” and “Combinations and Permutations built upon constant harmonic Density Increase and Melodic Distractions.” Metal Machine Music, manipulated white noise, is essentially tuneless and melody-free—yet at the same time the album asks, requires, really, that we reassess what “melody” is, and means. What’s music, for that matter, when made by machines?

In his liner notes, Reed pens a half-serious defense of the album (in his tone, you catch a bit what of Mick Jagger in a different context called “speed freak jive”). One of the great drug albums of the 1970s “is not for parties/ dancing/ background, romance,” Reed warns us. “This is what I meant by ‘real’ rock, about ‘real’ things. No one I know has listened to it all the way through including myself. It is not meant to be. Start any place you like.” He adds, “Most of you won’t like this, and I don’t blame you at all. It’s not meant for you. At the very least made it so I had something to listen to. For that matter, off the record, I love and adore it. I’m sorry, but not especially, if it turns you off.”

He offers a remarkably of-the-era rationalization of the album as a junkie’s modus operandi, specifically an “agreement one makes with ‘speed.’ A specific acknowledgement, A [sic] to say the least, very limited market.” Metal Machine Music was created by, and for, those “for whom the needle is no more than a toothbrush. Professionals, no sniffers please, don’t confuse superiority (no competition) with violence, power or other justifications” He goes on to suggest that speed freaks are of a nobler sort, blameless for either of the World Wars, “or III. Or the Bay of Pigs, for that Matter. Whenever.” But seriously, and “As way of disclaimer, I am forced to say ,”

that, due to stimulation of various centers (remember OOOHHHMMM, etc.). the possible negative contraindications must be pointed out. A record has to, of all things Anyway, hypertense people, etc., possibility of epilepsy (petite mal), psychic motor disorders, etc., etc., etc.

Duly noted. These notes are naked. Reed always seemed to be half-kidding in nearly everything he said or did, yet these liners are, in retrospect, remarkably candid and, in their conceptual way, very honest.

Depending on who did the talking, the execs at RCA were either appalled, indifferent, or impressed with Reed’s results. Bangs? He was blown away, going so far as to call Metal Machine Music one of the greatest rock and roll albums ever. His now-legendary takes on the album appeared in the Fall of 1975 and early Winter of ‘76 issues of Creem, and ricochet off of Reed’s liner notes. (Bangs seems to have used them as prep.) Sometimes Bangs agrees with Reed’s assessments of his own album and career; sometimes he vehemently pushes back. His descriptions of the album’s notorious abrasiveness are Classic Lester:

You know when you get so tense and anxiety-ridden that all the nerves at the back of your neck snarl up into one burning ball? Well, if that gland could make music, it would sound like this album.

This is what it sounds like in Lou’s circulatory system.

He touts the record as a great hangover cure, “Because when you first arise you’re probably so fucked (i.e., still drunk) that it doesn’t even really hurt yet (not like it’s going to), so you should put this album on immediately, not only to clear all the crap out of your head, but to prepare you for what's in store the rest of the day.” He champions the album as “the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum.” Number Two on the list: Kiss Alive!

Etcetera. More thoughtfully, he echoes what many felt at the time: that Metal Machine Music was a career suicide move on Reed’s part. For his part, Reed always lauded the album for its nervy, mold-breaking artistry, and was fond of it to the end of his life. (Reed died in 2013; in March of 2002 at the MaerzMusik festival in Berlin, in collaboration with the arranger Ulrich Krieger, he worked with Zeitkratzer, an experimental classical music group that played the original album in full.) To Bangs, Reed, in his aggressive manner, championed the album’s subtleties, claiming that the machine-abetted drones are in fact rich in harmonics, that only on headphone can one truly appreciate the mix (“…because there’s left and right but there’s no center. It’s constantly changing and sometimes one channel goes out entirely. There’s infinite ways of listening to it”), and that he’d embedded sonic nods to well-known classical music within the record’s seemingly impenetrable walls of noise.

“[The album] was a giant fuck you,” he acknowledged to Bangs, “but not precisely the way you are saying it,” adding, “When you say ‘garage music, well, that’s true to an untrained ear maybe, but there’s all kinds of symphonic ripoffs in there, running all through it, little pastoral parts, but they go by like—bap! in five seconds. Like Beethoven’s Third, or Mozart…” He crowed to Bangs that the president of Red Seal, RCA’s classical music imprint, was amazed that Reed was quoting Beethoven’s “Pastoral,” “and “it blew” Reed’s mind that he knew about it. “Because like there’s tons of those things in there, but if you don’t know them you wouldn’t catch it.”

Just sit down and you can hear Beethoven right in the opening part of it. It’s down here in, like, you know, about the fifteenth harmonic. But it’s not the only one there, there’s about seventeen more going at the same time. It just depends which one you catch. And when I say Beethoven, y’know, there are other people in there. Vivaldi... I used pretty obvious ones.

At this point, Bangs dryly suggested to Reed that the two of them should sit down in the near future, “with a tape or the record and you can point these out to me.”

“Un-uh. Why?”

“Because I’m not convinced.”

“Well, anybody who gets to side four is dumber than I am,” Reed reportedly said of Metal Machine Music. I’m dumber than Lou, then. I’m not a classical music aficionado, and can’t claim that I hear the quotes that Reed insisted are in there, at least consciously. What do I hear when I listen to the album, beyond the droning screeches of feedback?

I hear:

demented church bells tolling

distorted bagpipes

heralding trumpets

a boisterous city festival

a crowd cheering

a squeaky door opening (no sorry, that’s my wife Amy coming in from the garage)

a incessant beeping machine at a convenience store

a crying baby

my own ears ringing

screeching birds (mostly seagulls)

a cat meowing (!)

aimless tuning across frequencies on a radio

in the album-ending locked groove, a car engine trying to turn over and over and over…

What images do I conjure a I listen? An industrial waste site at dusk, a scratched-up chalkboard, a lonely astronaut out in space facing a deck of forlornly blinking lights, shitty analog television reception, a vague but violent act caught on a surveillance camera…. Interestingly, very little of what I “see” when I listen to Metal Machine Music evokes childhood or adolescence, as this is a very adult album, frowning in its insistence that the world is often a very ugly and caustic place to live in. As I listened I grew bored, and then annoyed, and then highly attentive again. I drifted, I refocussed. I heard nothing at all; I heard a lot. I developed a mild headache and grew anxious. I was impatient for the fourth side to end, and yet melancholy that the sound experience-event was going to be finished.

A conventionally ugly sounding record, Metal Machine Music became beautiful to me after I stopped trying to translate it, and, rather, allowed it translate me. In short, the album feels like life, evokes the transgressive, disruptive, and discordant impulses in living in graphic and powerful ways—and we experience many of those, every day, though we wish them away, or turn from them. The album accesses our unconscious, mimics our darker instincts and desires, and acts as a kind of deranged parallel soundtrack to the more civilized ways we walk through the day. And because it so genuinely feels like those aspects of being alive, the album’s beautiful to me, and really, and strangely, moving, beginning in media res with that crude tape splice and ending—or, actually, not ending—with a locked groove. Profound stuff, hardly the indulgent, throw-away joke that I’d read and heard about for so many years

After listening to Metal Machine Music? Well, I felt a bit altered, as if someone had spiked my drink and the effects were now wearing off. I was reminded of an insight that Joan Didion lands on in her great little essay on her migraine headaches, “In Bed” from The White Album. Pulling wide near the end, she takes on pain at large, and wonders to what else it might possibly be in service except suffering. (Blessedly, I’ve never suffered from migraines, but after reading Didion I feel something close to empathy for those who do.) The pain comes, she says, “and I concentrate only on that. Right there is the usefulness of migraine, there in that imposed yoga, the concentration on the pain.”

For when the pain recedes, ten or twelve hours later, everything goes with it, all the hidden resentments, all the vain anxieties. The migraine has acted as a circuit breaker, and the fuses have emerged intact. There is a pleasant convalescent euphoria. I open the windows and feel the air, eat gratefully, sleep well. I notice the particular nature of a flower in a glass on the stair landing. I count my blessings.

Her intense pain precedes relief, which presses the re-set button for her. Leaving Metal Machine Music behind, I felt something similar occur for me: the melody in the next pop song that I listened to put that much more of its hook into me; the chorus was that much more transcendent; the key change in the bridge that much more moving. I counted my blessings. But, honestly, I counted them during Metal Machine Music, too.

Oh, had the universe worked out to have gifted us with a Joan Didion profile of Lou Reed! Alas, the great dry and skeptical Anti Bangs never got her chance.

“Metal Machine Music is not chaotic. It’s not a John Cage experiment in aleatory music. It changes as it moves through time, but those fluctuations ‘mean’ nothing to me.” This is music journalist Jim Higgins, in his recent book Sweet, Wild and Vicious: Listening to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. “It is impenetrable,” he continues.

It is like the neutrino signal from space that scientists detect in Stanislaw Lem’s His Master’s Voice. They desperately want it to be an intelligent transmission. They find or force uses from it. But at the end they are no closer to understanding it, or even certain if it is something that can be understood.

I don’t know that Metal Machine Music needs to be understood in any conventional sense, only experienced, the way those glimpses of the dark side, the shadowy underneaths, can come unbidden to us, feared and dismissed, maybe, but no less a gift for that.

Lou Reed “Prince de la nuit et des angoisses” painted portrait DDC_8904 by thierry ehrmann via Flickr

I appreciate you doing the experiment. I haven't listened to the album, but I do appreciate (and recommend) the reader comments on George Starostin's site: https://starlingdb.org/music/reedc.htm#Music

I think my favorite is the first one:

"I actually have this, I actually listened to it all the way through, and I actually liked it. I don't know why - there's something about all those squeals and squelches and mechanical drones and fast mini-melodies I found interesting. Which isn't to say I've listened to it again. Someday soon, I'll get the urge and I'll probably like it again. For an album that's nothing but God-awful atonal noise, it's pretty good. It's certainly more of an artistic statement than my wife's vacuum cleaner although I had a Buick that was much more expressive and heartfelt ..."

Great review. It's been a while since I listened to MMM but back in my 20s I used a rotation of it, early Swans, Celtic Frost and Napalm Death to help me power through college essays. There's a ton of raw power in the music and a LOT of hidden secrets. It's like Lou took us along for a series of aural hallucinations.