My Life's a Mess

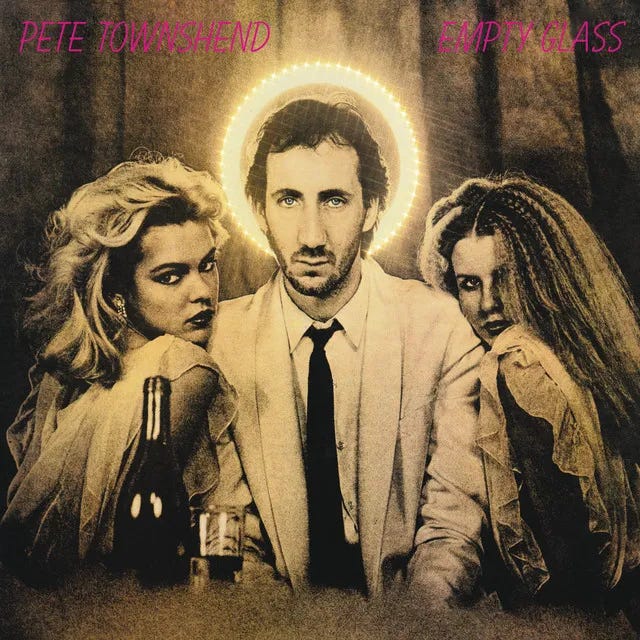

If you want graphic Pete Townshend autobiography, look no further than Empty Glass

Five years years ago, Pete Townshend published a memoir, Who I Am, which I liked at the time but which hasn’t grown on me well. Though stuffed with some terrific details of 1960s rock star culture—including the best on-the-ground description of the Beatles I've read by a musical contemporary; it was their their potency, Townshend marvels, that astounded—and some characteristically Townshendian discourses on the spiritual magnitude of songwriting, the book clouds over in the second half with the author's unfocused musings and obsessions. In places, his bafflement in the face of his own philandering and general ill behavior gets tiresome and predictable. The two takeaways for this reader: 1) Townshend really, really loves sailing; and 2) he’ll probably die in front of his laptop, with fifteen music composition tabs open.

If you want more graphic Townshend autobiography, look no further than his 1980 solo album Empty Glass, a personal and deeply idiosyncratic memoir-in-songs. Throughout the record, Townshend’s famously expressive, inexpert voice dramatizes his internal struggles and reflections; his singing is naked. He writes about love, sex, writing, death, and fame—each a longstanding passion for him—in material and spiritual iterations; the songs alternately rock (“Rough Boys”), lilt (“Let My Love Open the Door,” “A Little Is Enough”), and leave the earthly realm in a kind of hymnal bliss (“And I Moved”). Each of the ten songs reflects an aspect of Townshend’s complex and contradictory persona—it’s Quadrophenia, all over again—and the songs fail to resolve those tensions. Townshend was a drunken and drug-addled (and Keith Moon-grieving) mess when he wrote the album, and the desperation in his personal and public lives is given shape in fascinatingly different ways in the songs. In short, Empty Glass is a lesson in the richness, limitations, and value of the autobiographical impulse. Sometimes I joke about teaching the album in a Memoir class; other times I’m dead serious about doing that.

The title track is the standout. The verses trade Townshend’s spiritual concerns—the meaning of living, the uselessness of materialism, the shallowness and vivid promises of rock star posturing, the endless cycle of physical excesses, Ego versus God—his voice at turns mocking and confessional, chiding and vulnerable. The song begins aggressively, Townshend barking over a single, insistent guitar note, and the verses are melodically and rhythmically upbeat, gladly doo-wopping their way along, until things change dramatically at the chorus, when the tone abruptly, and movingly, shades toward confession:

My life’s a mess I wait for you to pass

I stand here at the bar, I hold an empty glass

The melody's heartrendingly beautiful, and Townshend, as he does often when moved, sings near the top of his register, yearning and unembarrassed. This brave and pathetic tavern confession—or is it supplication?—is soon elbowed out of the way by the return of the assertive verses and some classic Townshend guitar licks. (Wasn’t this the man who said that rock and roll allows you to dance all over your problems?) Yet the chorus returns, of course—it’s the reason the song exists and what it spins outward from, and the truth the singer can't dance away from, or ignore. A playlet, "“Empty Glass” is theatrical, almost absurdly so—you can virtually see the lone spotlight on Townshend as he sings this passage—but the honesty of the lyrics and vocal is real.

Near the song’s close, Townshend bravely tries one more time to balance the prayerful desolation and dissolution in the chorus with, what, good cheer? Empty bromides? A pep talk?

Don’t worry smile and dance

You just can’t work life out

Don’t let down moods entrance you

Take the wine and shout

More likely another self-erasing excuse to get wasted. Either way, it doesn’t take, unsurprisingly, and that haunted and haunting chorus returns—to my ears, among the most moving and powerful passages Townshend has written—as the weary, accepting guitar notes fade at the song’s unresolved end.

In a 1980 Rolling Stone interview with Greil Marcus, Townshend explained the song’s genesis:

“Empty Glass” is a direct jump from Persian Sufi poetry. Hafiz—he was a poet in the fourteenth century—used to talk about God’s love being wine, and that we learn to be intoxicated, and that the heart is like an empty cup. You hold up the heart, and hope that God’s grace will fill your cup with his wine. You stand in the tavern, a useless soul waiting for the barman to give you a drink—the barman being God. It’s also Meher Baba talking about the fact that the heart is like a glass, and that God can’t fill it up with his love—if it’s already filled with love for yourself. I used those images deliberately. It was quite weird going to Germany and talking to people over there about it: “This ‘Empty Glass’—is that about you becoming an alcoholic?”

The listener hears what the listener hears, filtering the song through her own personal drama and self-absorption and demons, casting sentiments written by a stranger as personal holy writ—that ancient and generous magic trick of art. In one of his greatest songs, Townshend essayed something deeply private and ended up somewhere eternal.

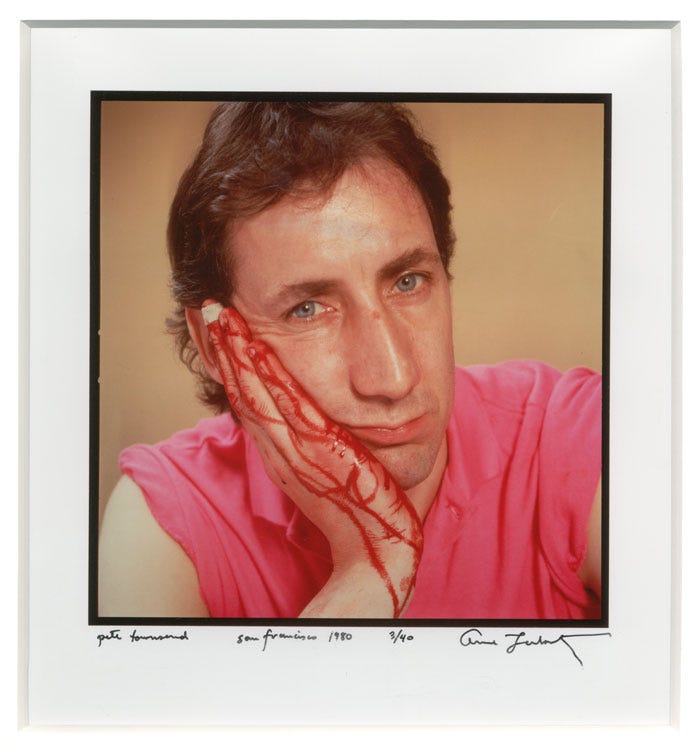

Pete Townshend: Photo by Annie Leibovitz via kimadababe (Flickr)