Poor boys

The Everly Brothers harmonize the lures and the pitfalls of cold, hard cash

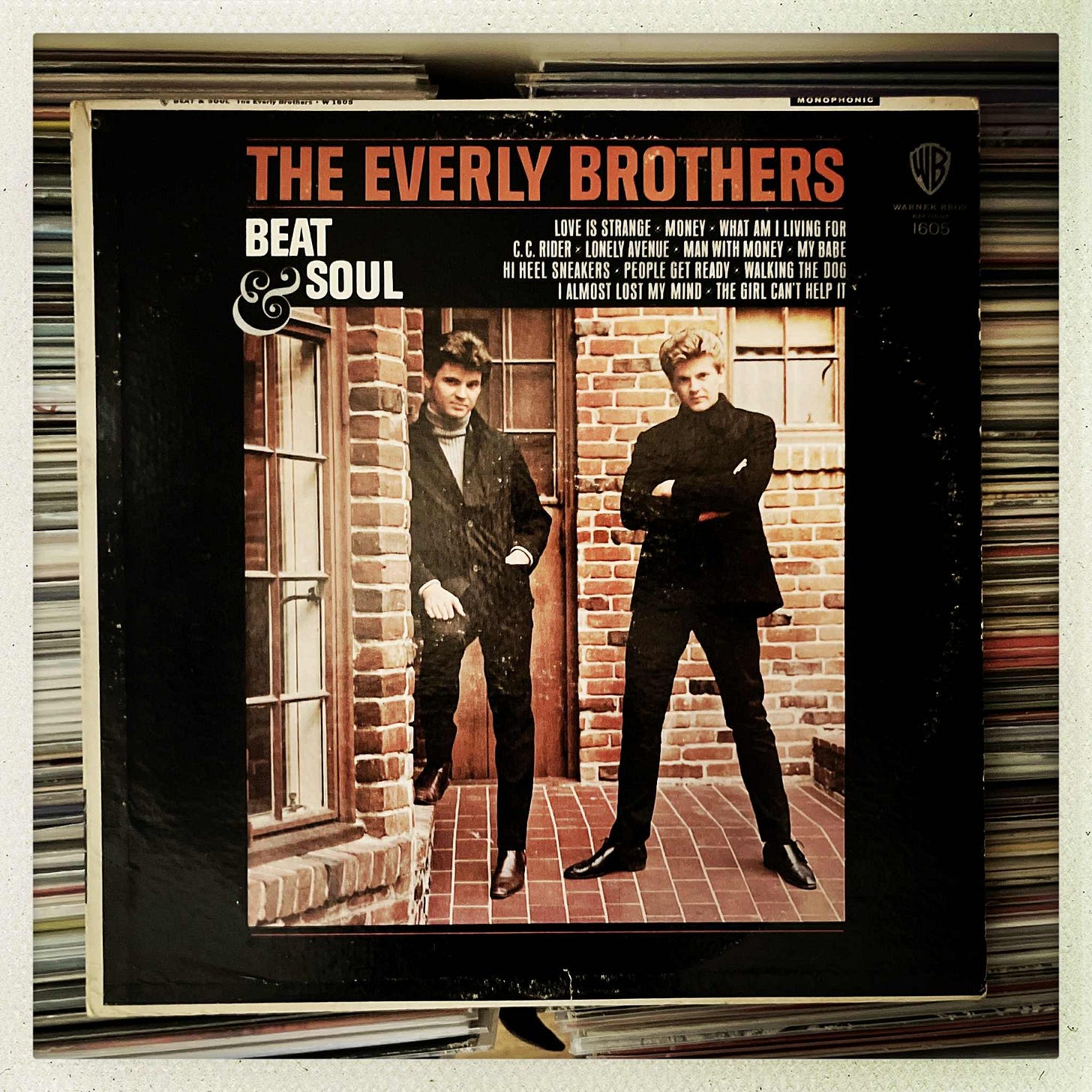

By the mid-Sixties, the Everly Brothers were facing some tough times commercially in their home country. Only two of their eight albums released in that decade sold in any measurable amounts in the U.S., and after 1964 only two of the numerous singles they’d issue would land in the Billboard Top 40. In ‘65, in the considerable wake of the Beat Group tsunami, they released a loosely-linked pair of albums, Rock'n Soul (in March) and Beat & Soul (August), neither of which sold much, though the single “Love Is Strange” reached number 11 in the always-welcoming U.K. singles charts. With cultural tides rapidly shifting, personal and health issues dogging them, and their sales and cultural cachet limping along, it’s grimly apt that Phil and Don would be singing about money.

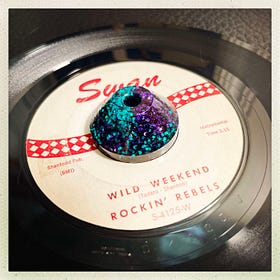

In 1965, Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)” was a half decade old already, and had been covered—both famously and obscurely—countless times, a staple for nearly every beat or garage group sent into spasms by the sublime groove and rockin' riff, not to mention that eternal cry in the title. Riffed casually at Motown’s Studio A in Detroit, “Money” was an inspired ricochet off of Buddy DeSylva, Lew Brown, and Ray Henderson’s “The Best Things in Life are Free,” from the 1927 musical Good News. Strong and Berry Gordy sang and banged on a piano before Benny Benjamin (drums) and Brian Holland (tambourine) joined the rent party. (Barrett’s claim to a songwriting credit has been hotly disputed down the years.) Benjamin and Holland are the stars of the recording, to my ears, their percussion the very sound of those longed-for coins jingling in a pocket. The song’s simple; you don’t need a complex melody or a fussy arrangement, just something basic that a forlorn kid might whistle on an allowance walk, eyeing the pricey stuff they can’t afford. When I saw the reunited Sonics at the Double Door in Chicago eleven years ago, the crowd, including a sizable portion of startled twenty-somethings, grooved to the band’s well-worn take on the well-worn “Money” as if it were last summer’s surprise hit, the lament as relevant as ever.

Sixty years ago, Phil and Don (or, anyway, their label Warner Brothers) felt obligated to toss their version onto the tilting cash pile of “Money” covers, and it’s a winner, muscled into ascension by a fantastic group of “Wrecking Crew” players gathered at United Recording Corporation Studios, in Hollywood. No less than James Burton, Glen Campbell, and Sonny Curtis played guitars on the Beat & Soul sessions—spread over a few days in June 1965—with Larry Knechtel (bass) and Jim Gordon (drums) as the ace rhythm section, and Leon Russell and Billy Preston pitching in on piano. (Other sources suggest that there were even more musicians involved in the recordings. Oh, but for someone to have wandered in to United with a Super 8 film camera!) Lamentably, we may lack specific details as to who played what on which tracks, but trust your ears; as arranged by Campbell and produced by Dick Glasser (the Ventures, Freddie “Boom Boom” Cannon), these tracks really swing, and land plenty of solid punches, especially in the mono mix. Dig the surprisingly nasty fuzz in “C.C. Rider,” a sinewy, electric “Walking the Dog,” and the raucous tears through “Lonely Avenue” and “The Girl Can’t Help It.”

And “Money,” too, catches fire. The famous riff's decorously invited in by some acoustic strumming, and then pushes everything aside, the musicians hanging on for the ride. Yet, naturally, the song belongs to Phil and Don, a sonic colonizing that they lorded over many of their cover versions, especially in the way they sing the title phrase—they goof on it, wink with it, and smile through it, country-twangin’ all over the joint, and never lose sight of its claim on them. When the brothers get excited, their close harmonies open outward, vibrantly, and they really belt it here, especially the backing vocals. I don’t often feel the urge to crank the Everlys—they usually dominate the room in more subtle ways—but I always reach for the the volume knob here. I bet Lennon dug it (if he bothered to listen).

“Man With Money” kicks off the second side of Beat & Soul. (It was also issued as the b-side to “Love Is Strange,” the sole single from the album.) I’m fairly in awe of this song and its arrangement and performance, which add dimension to the wailing “Money,” contributing a darker, even more yearning voice. What I want, indeed. The lone Everlys original on the album, “Man With Money” is obsessed and desperate, sung with urgency and played with the kind of defiance that hopes to bully away all of the song’s problems. To wit: the singer needs cash, because his girl thinks that “money makes a man,” and yet he’s “a poor boy.” The way the Everlys sing that phrase, forlornly, resignedly, in a descending melody, exposes the emotional truth of the song. (“A Poor Boy” may as well be the unofficial song title.)

The assertive, four-four beat mirrors the singer’s resentment (the song’s his rapid heartbeat) as well as his resolve to do something about it. That something arrives in the astonishing middle:

Just down the street, I know a place

When they’re asleep, I’ll cover my faceI’ll break the lock, open the door

I’ll slip inside, I’ll rob the store

Up to this point, the song’s a well-acted story—you can virtually see the marks on the stage the actors hit—but the massive reverb in the middle tells us that we’re in the singer’s head now, where the most private stuff is. Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of the imagined heist, the naiveté echoed by an overeager keyboard: this is feverish stuff for the singer, who needs to hide behind a mask not only for anonymity, but because he’d have to be a wholly different person in order to be a thief.

The mounting, Spector-ish drama in this passage—launched with an obsessive 3 a.m. repetition of man with money, man with money, man with money muttered by the singer to the bedroom ceiling—could’ve easily veered into melodrama, and some might feel that it does, but to my ears the Everlys sing the despair so fervently that the fears, regrets, and faux courage feel all too genuine. The full band comes crashing in after the dream sequence, tasked with puffing up the singer’s tenuous bravado, and the performance really starts to accelerate. Things get loud, and threaten to careen, but we never get to the robbery scene in this particular movie. The song fades (appropriately, as there’s no resolution for this poor kid, not until he grows up a bit), and the title, sung over and over, is the inner voice of a loserdom that he shouldn’t bear and yet can’t shake.

(Bruce Springsteen was listening, I’m pretty sure of it. And, for that matter, so was Pete Townshend: the Who cut a version of “Man With Money” during the fall 1966 recording sessions for their second album, A Quick One. Townshend, through a maturing Roger Daltrey, likely identified with the singer’s hangdog persona, and they both probably loved the dramatic middle; Townshend’s guitar slashes and burns and spits feedback at the required moments, and John Entwhistle and Keith Moon try hard to run over the song, as was their modus operandi. The Who’s version, finally, is affably respectful, and I’m baffled as to why the band didn’t include it on the album, or as a b-side to, say, “Happy Jack.” In the event, the recording collected dust until A Quick One was reissued in 1995.)

“Man With Money” is a great pop song—powerfully sung, with steep dynamics and a commanding group performance, the guitars and propulsive rhythm bed rocking hard. (In his Leon Russel biography Superstar in a Masquerade, William Sargent reports that Russell plays the track’s mixed-low piano). I find the rock and roll attack of the pretty melody moving, the yin and yang of fantasy/desire and all-too-real reality. As for the points of view: different angles expose different truths. Is she a shallow “gold digger,” that tired trope? Or is she a smart chick, unwilling to waste time on a guy who can’t support himself? She isn’t given a verse.

“When Phil and I hit that one spot where I call it ‘The Everly Brothers,’ I don’t know where it is,” Don Everly once remarked. “Cause it’s not me and it’s not him. It’s the two of us together. I sing the lead, and so I can drift off. Then we’ll come back in together and the whole thing happens again.” He added, “It amazes me sometimes.” In the middle passage of “Man With Money,” the first two lines are sung solo, the last two as a duo. The Everly Brothers have the sublime knack for inhabiting the concerns and anxieties and elations of a lone individual and bringing them to life with two voices, thickening the emotional grist of their songs. It’s a kind of a magic trick, and it often tightens my throat in the process: the Everly Brothers’ songs routinely move me to tears.

There are the great, oft-played hits that everyone knows, and then there’s the less celebrated “Man With Money,” a poignant, bracing tune about sorrow and hopelessness sung with optimistic gusto. The song’s the dejected flip to “Money”’s half grin; crestfallen with the knowledge that the money they want, and the freedoms and prizes and affection that they think it’ll bring them, are unobtainable, Phil and Don seem to be walking a few paces ahead of Barrett Strong. He’ll eventually catch up with them, and they’ll share a complicated look. Tomorrow, someone somewhere will have a bill to pay, a dinner to buy, the rent to cover, peer into their wallet, and the songs will start all over again.

You might also dig:

You get what's given to you

"No future!" sounded the clarion call of 1977, and the Sex Pistols made it personal: no future for me or for you. As dramatic as that line was—is—and as simply and brutally as it articulated what so many were feeling, a lot of kids in the U.K. in the mid-70s had more immediately pressing needs than to fret over a bleak horizon: I got no money to spend

Something I would find hard to write

“When I find a cover song that I like, I’ll work away at it until I kind of believe that I wrote it.”

“Everly Brothers 1965” (background blurred) via Wikipedia Commons

That was great pairing two Money tracks—how Man wasn’t a massive hit I’ll never know. Have you heard The Eyes and Mirror Stars versions?

Solid essay, Joe.