Richard Goldstein on The Scene

His music columns for The Village Voice were incisive, dryly funny, and often prescient

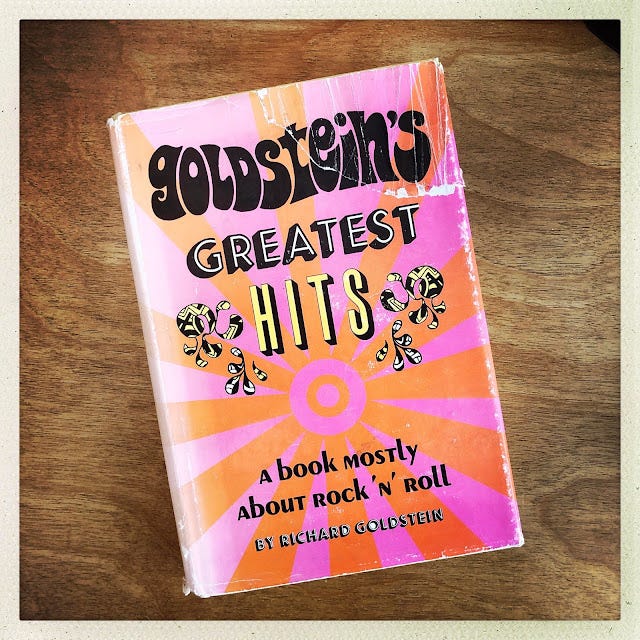

Richard Goldstein's "Why the Blues?" ran in The Voice in 1968 and was included two years later in Goldstein's first book, the essential Goldstein's Greatest Hits: A Book Mostly About Rock 'N' Roll. I love reading "on the ground" accounts of pop culture in transition, especially from the epoch-a-week 1960s. Here, Goldstein explores the trending blues revival among (white) musicians, seeing it as a rebellion of sorts against the sheen and artifice that much of the pop landscape had been adorned with the previous few years. Though that's thoroughly covered ground, Goldstein's take is worth a read given his pointed observations and droll amusement with the whole thing.

He situates the piece at The Scene, Steve Paul's music joint on West 46th Street (pictured below), where things have "changed a bit, grown stern and funky like the rest of us." Goldstein acknowledges that he can’t "listen to today’s rock without noticing the sound of shovels."

We are churning up the earth again, with the aim of re-fertilization, but with the immediate effect of killing off what happens to be growing—however poorly—at the time. Pop, of course, is all topsoil. It’s what shows—immediately, apparently. It catches the sun and receives the rain, and erodes first under the impact of trampling feet. I once chose to live off this topsoil because for a time, it was lovely to look at, and rich to the touch. As for the bedrock, I was satisfied to perceive that it offered vital support. But the surface was what turned me on.

Yet he's recognizing, with the blues reviving and the turbulent events of 1968 behind him, that pop music isn't providing what it used to. "The blues matters," he writes, "because it is always there when you need it—those 12 bars inviolate, self-contained, eternal. Blues is the humus of American music, but you have to burrow to find it. When the surface seems to shine of its own accord, all that spadework seems unnecessary." He adds, "When pop is vital, we are unwilling to sanctify the blues. But rob rock of its spasm-grace, and replace energy with a stylized motif, and suddenly, they are turning the topsoil under for nourishment from below." The blues revival he's witnessing is nothing short of a "requiem for rock. The simple fact is that the entire pop renaissance of the mid-’60s has failed to sustain itself beyond that first, shattering tonal wave."

That failure holds true far beyond the sphere of music. The pop sensibility—and its extension in painting, theatre, cinema, even politics—never moved from a mere fascination with the surface of things, toward a true metaphysics of the moment. The fragile alliance between intellect and energy which characterized pop art at its finest has fallen prey to the very abstruseness pop began as a rebellion against.

Given the "distressing...failure of pop to lead to anything," and that the movement, as he sees it, hasn't even "inspired its own antithesis," generating "no anti-pop, no rejection of the superficial as a fit subject for investigation"—though I wonder if he'd ever seen the Velvet Underground—Goldstein ticks off a number of crucial moves rock musicians must make as acts of rebellion. For one: "If rock is to retain its outcast’s appeal, it must renounce its alliance with the intelligentsia" and "declare the entire pop enlightenment null and void."

He cites The Doors and The Beatles, in particular "The White Album," as complacent, unthreatening pop—The Beatles, he argues, "are 'haves' in the most far-reaching sense of that word. They are the golden boys of pop, and we have no right to demand of them the consciousness of desperation which seems so appealing at the moment." The Rolling Stones' Beggars Banquet, on the other hand, is a truly relevant album, steeped as it is in the blues and roots music, away from pop glitter. "The question of relevance is no critic's conceit," Goldstein insists, "especially in rock, where it is the only truly relevant criterion." The Stones have responded "much more effectively to their audience’s demand for songs that sound like Rockabilly or blues." Though songs like "The Salt of the Earth” and "Prodigal Son" may be "calculated," they're "deliberate attempt[s] to draw bonds between the blues revival and themselves." Those otherworldly titans The Beatles? Goldstein sniffs that they seem "more than ever the creatures of their own cosmology."

In an exciting passage, Goldstein goes on to laud the MC5—providing early east coast critical support for the band that hadn't even released an album yet. The MC5's "open hostility to all that is 'gentle' in rock" moves Goldstein, because as "heroes of the new, down rock," The MC5 reflect "distrust—so central to current youth culture—of the ornate, the educated, and the efficient. In America, it is inevitable that the rock underground must embrace the blues...to maintain its position of seeming aesthetically 'pure' without being intellectual." In a terrific observation, Goldstein argues that the blues revival "is the first cultural appointment of the Nixon administration," signifying "a distrust of all innovation, when it is tied to popular appeal." Yet he's also shrewd enough to recognize that the then-new and wildly popular Bubblegum Music and the blues reflect "the same basic tensions in American life. Both seek refuge from complexity and disunity in the power of pre-existent forms," adding, "B. B. King and the Ohio Express are both a great consolation to their audiences."

There's a whiff in the piece of an earlier generation's unfortunate tendency to romanticize and sentimentalize the blues, and hence the hardscrabble conditions that produced much of the early blues, and by extension the unhappy situation of many African Americans. Albert King is "authentic," while Jim Morrison is a poser; Ma Rainey, "who is black and rural-real," is easier "to adore than Janis Joplin, who is white and nearly rich"—when Rainey would've gladly traded a privileged white man's well-intentioned adoration of her reality for the reality of a celebrated and well-paid white singer.

But on the whole, Goldtsein remains smart and ironically witty about race as it plays out in culture at the end of the decade. He ends the essay with a trenchant, devastatingly funny set piece at The Scene. Four white women are watching, and very much enjoying, Lightnin' Slim and Slim Harpo onstage, "smoking and sipping and staring down a convenient crotch. And the one sheathed in voile, with spitcurls on her eyelashes—turns to her friend with the listing breasts, and sighs,

“He really lays it down, that Lightnin’ Slim.” “Yeah,” says the other. “Didn’t he used to write for Cream?”

Goldstein sighs, "the blues revival is at best an interim, a necessary haven for pop refugees. It will matter to the bulk of America only in its popularizers," adding, "The man who emerges from some cosmic delta to instant acclaim as a superstar will be the one who reconciles blues power with the freaky exhibitionism of rock. I'll wager a year’s supply of Arhoolie records that he’ll be a white man."

Iggy Pop, your table's waiting for you to overturn.

“NYC - Greenwich Village: West 4 St-Washington Sq Subway Station” by Wally Gobetz via Flickr

“Richard Goldstein - Pop Conference 2015 - 03” by Joe Mabel via Flickr