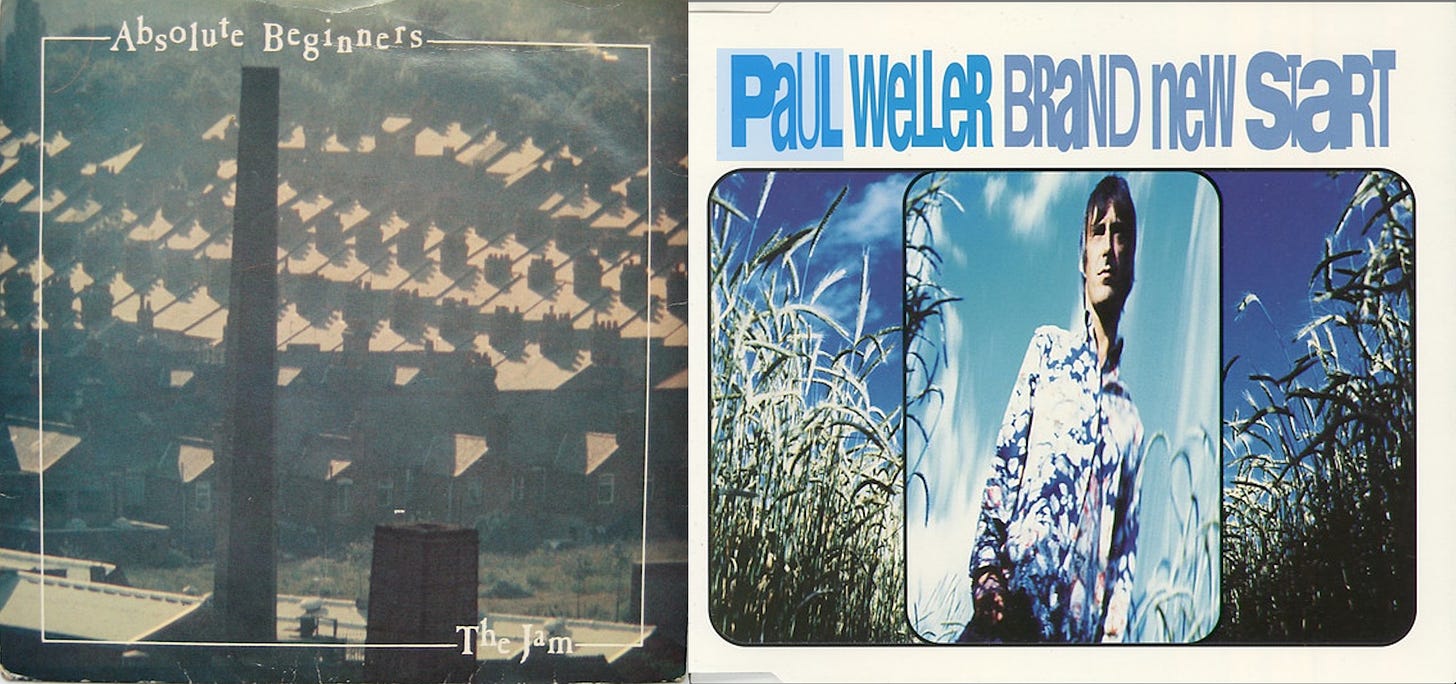

In 1981, The Jam released the single “Absolute Beginners” backed with “Tales From The Riverbank.” In the liner notes for the band’s Dig The New Breed live album Paul Weller would describe 1981 as “an ‘horrible year for songs!”, yet he obviously cared enough about “Tales From The Riverbank” to have shepherded it through a few iterations, including an early charging version titled “We’ve Only Started” (first released in 1992 on the Extras compilation) and in a horn-driven arrangement issued as a fan-club flexidisc at the end of the year. Allegedly both he and his label Polydor regretted not choosing the song for the A-side of the single.

Seventeen years later, Weller would stroll along those same riverbanks. In 1998, he issued Modern Classics, a best-of compilation of his solo work, including with it a new single, “A Brand New Start,” an ironic title given its rearward-glancing b-side. “The Riverbank” is a curiosity: neither a remake nor a wholesale rewrite, it sounds like a spirit cousin to the original song, the new, affiliated title suggesting a relative once-removed. There are certainly family resemblances: “The Riverbank” emerges in a slow up-fade as does the ‘81 song; the moody and atmospheric arrangements, cast by trippy guitars, sitar, and feedback, are similar; the songs are only a couple seconds apart in length.

So why did Weller revisit the tune? To redress the wrong of relegating a personal favorite to a B-side? Like many artists with long, sustained careers, he has been known to pick his old songs up off the floor and see if they still fit; he’s performed onstage and recorded in the studio countless songs from his Jam, Style Council, and solo catalogues in differing arrangements and with competing intentions. (As I wrote about here, his 2018 live version of 1980’s “Boy About Town” was revelatory.) Weller occasionally approached the same song from different angles during his eclectic Style Council years—the journey from acoustic version to big-band arrangement of “Headstart For Happiness” was especially audacious—but he rarely retitled a song of his, that gesture alone indicating that there’s something distinct about “The Riverbank.”

The differences between the ‘81 and ‘98 recordings are subtle: Bruce Foxton’s memorable bass-line, the strong undertow in the original song, is gone in “The Riverbank” (though it’s impossible for me not to hum it anyway when I listen); Weller’s vocal a decade and-a-half down the line is more wistful, and gentler. In the last line of the opening verse the singer now wishes to spread “joy and love” in the listener’s heart rather than simply “hope,” and in the final line of the second verse Weller jettisons the “too many to the pound” lament about vanishing green spaces for the more expansive, and sentimental, “place of hope and of endless times.”

The chorus differs slightly, but intriguingly, the original’s

True, it’s a dream mixed with nostalgia

But it’s a dream that I’ll always hang on to, that I’ll always run to

Won’t you join me by the riverbank?

replaced with

The truest of dreams, I live and I wonder

But it’s the scene that I’ll always hang onto, that I’ll always run to

Join me by the riverbank?

In the ‘81 version the singer acknowledges that the bittersweet sentiment he sings about is part dream, part nostalgia—that is, it’s all lost. In the '98 version the tone’s less rueful to my ears, as the dream is now “the truest” of visions, casting a spell and inspiring wonder. Coupled with Weller singing the title phrase in a gently ascending melody against the ‘81 version’s descending melody, the mood in “The Riverbank” is one suffused with gratitude. It’s a warm invitation, now. Generous too is the bridge, which in the ‘81 version is spooky and positively Welleresque in its grumpiness: because life’s “too cynical,” we lose “our innocence” and “our very soul.” Seventeen years later he sings:

A magical leaving when it’s time to believe in

The magic between us, the magic of innocence

I might be hearing Measured for leaving in that first line—I can’t find the lyrics online anywhere—but the adult wisdom in the words that follow rings loud and clear. Weller was nearing the age of 40 when he wrote “The Riverbank,” an already-long career and a personal life of ups and downs behind him, and maybe he was taking stock in the value of cynicism—the language of his twenties—and questioning its shelf life. Or maybe the further he gets away from childhood days spent in the countryside along quietly streaming rivers the more he cherishes the memory and no longer feels that he must apologize for its romanticism. It's time to believe.

Listen to “Tales From The Riverbank” and “The Riverbank” back to back and the impression is of waking from a vivid dream, the particulars of which are already fleeing from memory in the moments of rousing. That was wild, the dreamer thinks, the same song but also different somehow, and he chases its wind-blown remnants the rest of the long day.