The angel who's got the proof

In "Catholic Boy" and The Basketball Diaries Jim Carroll stared faith in the face and talked back

Several years ago I wrote about how being raised Catholic meant that I was bound to a certain authoritarian guide book when it came to the enjoyment of popular culture. When my siblings and I wanted to see a new movie, I wrote, “my parents would consult the Catholic Standard, the weekly Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington, D.C.’s, official newspaper that materialized on our kitchen table with solemn regularity. The editors at the Catholic News Service classified each new movie with a letter rating reflecting the movie’s morality and intended audience, from A-I for general patronage, to L for a limited adult audience, to O—the letter I’d both dread seeing and thrill to—for morally offensive. As I recall, these ratings were fairly ironclad in the house; my mom had great faith in the Standard’s standards, and though the ratings were meant as a guide, we lived by them.”

When Billy Joel released “Only The Good Die Young” in 1977, a track from his album The Stranger, the song landed in my suburban house like an uninvited guest from whom my well-meaning parents tried to shield me—which only made it more illicit, of course. “Released as a single, ‘Only The Good Die Young’ was, I quickly discovered, anti-Catholic. More specifically, it was a paean to getting up a good girl’s skirt. I’d learn much later that the Catholic Church–affiliated campus radio station at Seton Hall University had banned the song for its satiric lyrics hostile to spiritual purity, sexual chastity, and church teachings. Other less-secular-leaning stations had joined the protest, and soon the song reaped the predictable rewards of infamy: it rocketed up the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, peaking at number 24.

“You Catholic girls start much too late, Joel sang, and though I was a bit young to get it, I got it, especially as the song became incendiary under my parent’s watchful eyes. I think [my older brother] Jim bought the album, but I believe we weren’t allowed to play it in the house—or, at any rate, we were strongly discouraged. But I heard it: when my brothers’ friends would come over to play it out of range of my parents; I heard it on the radio; mostly I heard it in my head when at night in bed I’d score the changing postures of the girls at school from playful to assertive, virginal to whatever-was-next, the glowing horizon of bras and underwear, romance and sex, just there and just out of reach.

“The panting insistence in Joel’s song—which he wrote about a crush on a girl in high school back at Levittown, Long Island, where he grew up— was murky language to me, but one it seemed that my older siblings were speaking already, or knew enough stray words of to claim as their own. Joel smirks: ‘I might as well be the one.’ To do what? I wondered. My siblings were closer than I was to understanding, to dealing with the song’s winking carpe diem, and this glaring distance between them and me hurt, producing a chest-tightening anxiety that I’d never catch up with them.”

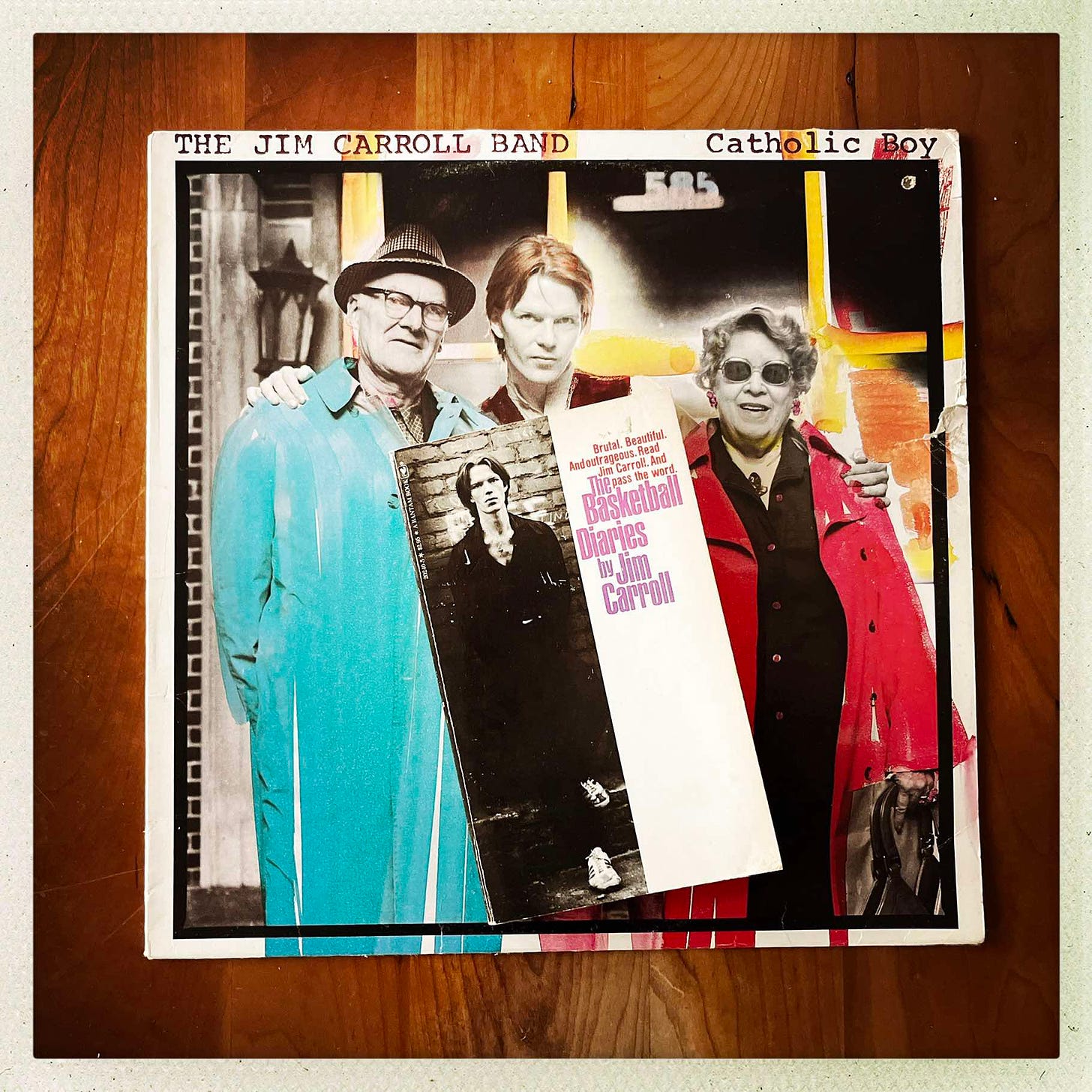

One song that I would’ve had some trouble catching up with as a newly-minted teen was The Jim Carroll Band’s “Catholic Boy,” a scabrous anti-anthem that I’d ultimately hear years after I’d “fallen away” from the church. “Catholic Boy” wasn’t issued as a single—the raucous “People Who Died” was—but as the title track of Carroll’s heralded, charging debut it signaled an equally bold and nervy persona.

Carroll formed his band in the Bay Area, where he’d moved from New York City in the late-1970s to kick his heroin habit and to reap the benefits of new, warmer scenery; there he hooked up with Patti Smith who invited him onstage one night in San Diego to sing with her band. Turned on, Carroll recruited the members of the Bay Area band Amsterdam—Brian Linsley and Terrell Winn on guitars, Steve Linsley on bass, Wayne Woods on drums—and cut a series of demos. Back in New York the tapes landed in the hands of Earl McGrath, then the head honcho at Rolling Stones Records. Allegedly Keith Richards cocked an ear to the demos and dug them enough to kick the requisite wheels in motion at competing labels. In the event, Carroll signed with ATCO which issued Catholic Boy in January 1980.

With its deeply ingrained sacred rites and mysteries and equally ingrained hypocrisies and flaws, Catholicism was as central to Carroll as basketball, girls, and drugs. Raised in the faith, he attended Catholic schools as a boy and teenager in the Lower East Side and Upper Manhattan—eventually lured away by more “secular” interests, he nonetheless felt tattooed by his religious experiences. In 1978 he published his fantastic Basketball Diaries, a gathering of journal entires he wrote between the ages of 12 and 16. Bitter recollections of the Catholic church and school teachers ooze through the cracks. “Catholic schools are sheer shit,” he writes, “madmen in fucking collars who in their pious minds can never be wrong, running around with their rubber straps beating asses red for the least little goofing, and pushing into a bunch of stiff noodle-sized brains that ‘Who made us?...,’ ‘God made us... ,’ horse drip. The old biddy penguins they call nuns are even worse. I’m cracking back the first cat who tries that ‘bend over’ shit, hoping they give me the boot quick.” He eventually stopped attending Catholic school, “so those fucking penguins were not going to screw my ass one bit longer.”

In a passage dated “Winter 64”—he would’ve been around 14 or 15 years-old—Carroll acknowledged that though he was baptized a Catholic, “my moms and pops never made us go to church except maybe Christmas to hear the shit choir croak out them goodies, and in fact they never made us go either. So I never made first communion or got confirmed or whatever it is and least of all been to confession.” (He was in for a rude awakening at his new school in Upper Manhattan, where the sacrament of confession was required. “Now they throw this shit at me and a friend tells me you’ve got to wait until everyone is finished, and it might take an hour maybe if there are only a few priests handy to dish whatever they do out.” He “tried to beg off,” but to no avail.)

Carroll’s dry admission that he’d actually skipped the sacraments of communion and confirmation colors the lyrics to “Catholic Boy,” a lurid, feverish reckoning with his faith and its aftermath. The track closes out the album, its benediction of sorts. As with all great closing tracks it reorders what came before, making some things explicit— “You get nothin’ back for all you’ve saved / Just eternity in a spacious grave” (“Nothing is True”); “I want the angel who’s got the proof / She signals her devotion from the rails on the roof” (“I Want the Angel”)—and leaving other things implied.

The song begins as a garage band stomp, two snarling guitar chords that would cut you if you got too close; muscled by Woods’s emphatic, impatient snare drum the song lurches forward. I was born…, Carroll begins, echoing Richard Hell,

And I spat on that surgeon and his trembling hand

When I felt the light, I was worse than bored

I stole the doctor’s scalpel and I slit the cord

What follows is a series of vivid, scornful set pieces. The singer, born premature, curses at other children in the ward; having escaped the womb he’s charged with theft and ends up in jail (“The Tombs”) where he’s starved and taught to fear and where he forges “allies in heaven” and “comrades in hell.” Released from jail, he emerges as a kind of blessed, fevered anti-saint in the presence of whom “angels dance and drop to their knees” and “the feet of statues bleed” and who now understands the fates of his enemies “just like Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane.”

Behind all of this the band plays assertively, alternately strutting and prowling through the song’s rudimentary twelve-bar joint with juvee smirks, looking for trouble. Carroll talk-sings in his acerbic style; whether he’s reciting poetry or singing a rock and roll song, or both, that’s up to your biases. (“Music without melody,” he once dreamed, “where my voice would simply be another rhythm instrument, like a drum.”) The song’s only true melodic moment arrives in the chorus, courtesy of a lilting guitar line that scores the song’s greatest discovery:

I was a Catholic boy

Redeemed through pain

Not through joy

I hear a half grin and an eyebrow raised as Carroll sings that last word.

Near the song’s close, Carroll gets his hands around his chief complaint: he makes a contribution, he gets absolution. It’s hardly a novel insight, but coming late as the song’s dream fever crests the line rings true and ugly. He may resolve to purify his soul, but the litany he spits out in the song’s closing vamp will only muddy up that purity. They can’t touch me now, he smiles, because he’s got “every sacrament” behind him, that old deathbed-confession saw. He gleefully ticks the boxes: he’s got baptism, communion, penance, extreme unction, confirmation. (The way he sings “confir-may-tion,” with a shiver of joy at everything he’s getting away with and is proven true to him daily in the fallen world.) And now that he’s “a Catholic man” he’ll put his tongue to the rail whenever he can. That last line closes down the song, and it’s as if the song and the band playing it have no choice. Where else can it go after a kiss off like that? Bam-bam-bam-bam goes the band. They’ve done their part.

Carroll is, of course, lying. But whether it’s in Basketball Diaries or “Catholic Boy,” I don’t know. If he in fact never received first communion and confirmation, as he claims in his journals, highly unlikely for a Catholic into his teen years, then the lines in “Catholic Boy” become goth-like stories, amplified autofiction. Of course even for the devout, the church’s mysteries can live inside like daymares.

“I love the rituals of Catholicism. I hate the fucking politics, and the Pope and the Curriers and shit, but I mean the rituals of it are magic. I mean the mass is a magic ritual for God’s sake, it’s a trans-substantiation! I mean, the stations of the cross, the crown of thorns, getting whipped, I mean its punk rock, you know?”

That’s Carroll talking with Legs McNeil. He related to McNeil that talk show host Tom Snyder had wondered to Carroll if such a point of view might be considered blasphemous by some. Carroll replied No, he was “coming from a very reverential point.” Carroll added, “I mean, it wasn’t like we’d go to church or anything like that…with Catholic school, it’s not like Protestant religions, you hardly ever read the Bible. With Catholicism, we’re beyond the Bible, we’ve been around a long time, and we don’t have to read that stuff anymore! Like, ‘We’ll interpret it ourselves, just listen to what this top guy says and do it!’ So I didn’t know the Bible that well, I did know the New Testament much better than the Old Testament.”

If I’d heard “Catholic Boy” when it came out, I would’ve both loved and been scared by it. At age 14 I wasn’t close yet to vibing off of Carroll’s leering, sarcastic, accusatory take on Catholicism—that would come later—yet I was already, like Carroll, tattooed by the magic and gory strangeness of the rituals of Mass. For several years I was an altar boy at Saint Andrew the Apostle, and what I absorbed there—before mass watching a preoccupied, surly, and very human priest preparing; hoping against hope that something would actually transpire during transubstantiation; the urge to fight the urge to mentally undress the girls in the pews; the genuine thrills and anxieties during Stations of the Cross; the scent of incense that I will never be able to shake; and the rest—became over time a story stuffed with symbols, metaphors, lyric language, poignant songs from the choir. I get Carroll’s take now. Offered in a rock and roll song, it means even more.

Here’s a nice ragged take of “Catholic Boy” recorded off a live radio broadcast of a gig at the Old Waldorf in San Francisco on August 15, 1979 five or so months before the album’s release.

“Jim Carroll, poet, author, musician (New York, NY 2005)” via Creative Commons

Photo of author ©Joe Bonomo

Great write up! Joel did a great job at crafting a song that had both mainstream appeal and a half dozen innuendos to get past moral walls. Also, thanks for introducing Jim Carroll! His stuff is news to me, so thanks for the find.

Jim Carroll is one of my absolute favorites as a poet, musician, and memorist. I read The Basketball Diaries in high school and it has served as a holy book for me since—and is one of the primary influences for my YA novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, which features a high school Native American basketball star.

I'm confused about your point that there's no live video of Carroll performing live. Here he is on the show Friday, that brief, weird cousin of Saturday Night Live:

https://youtu.be/Ly6j7bE6BOc?si=PmXFIOC3xtd6ZYfP