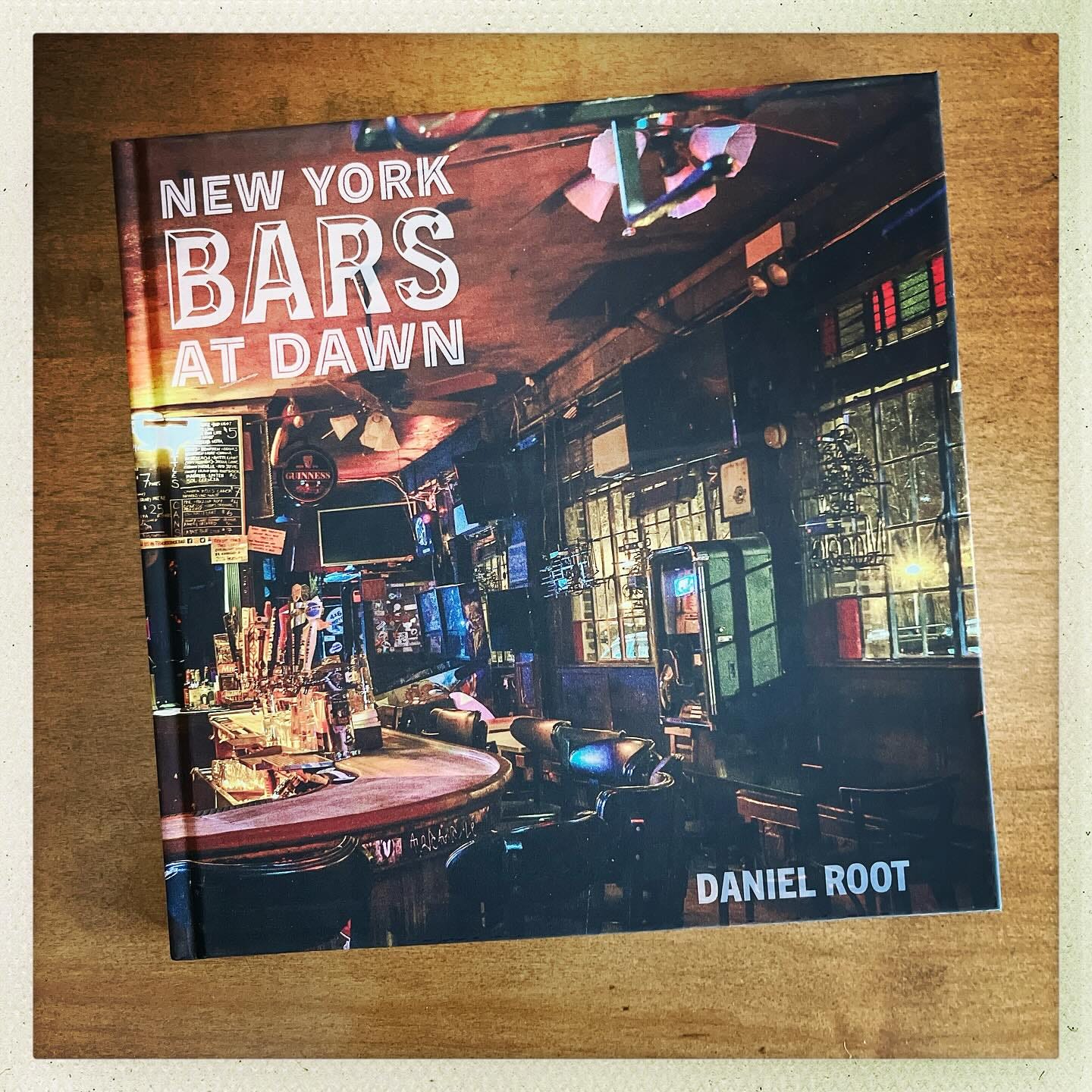

In his remarkable new book New York Bars at Dawn, photographer Daniel Root documents a world that’s somewhere between poles: dark and light, barren and peopled, closed and open. The book is a graphic reminder that the cliché of a sleepless New York originates, as all clichés do, in a startling truth. Even dozing, these bars are awake to colorful light and fantastic presence, and the ghosts of their patrons materialize page after page. Root has for years been posting his photographs at his wonderful Instagram account, and if you love cities, bars (both well-heeled and dive-y), and the play of light and shadows as I do and haven’t yet checked out the site, prepare to lose the afternoon.

I recently spoke with Root on the phone. He was generous and easy-going, and eager to talk about his book, which was born out of his propensity for daily, pre-sunrise walks in the city, a way for Root to manage his mental and physical well being. “I have always needed to move physically,” he told me. “And I mean, I’m talking about as a three year-old on. And walking is a very calming action to do right now in my life. And I like the pace of it.” We bonded over our mutual love of New York City—he’s lived in Alphabet City for four decades—, bars, drinking, and photography. We lamented the late-great Lakeside Lounge on Avenue B and that he never had the chance to photograph the infamous Mars Bar among other long-gone joints, and we shared an enthusiasm for Virginia Woolf’s great walking essay “Street Haunting.”

I began by asking Root if he thinks that what he’s doing is coming out of any particular tradition. “I’m happy you asked that question,” he said. “I think it’s a really good question because, like, where does it come from? I'm not really sure. Except for the peacefulness of walking. And all that walking allows—I’m not a yoga guy, or I don’t know if it’s spiritual, or whatever—but the almost meditative quality of a walk allows for all this to kind of flow through and in and filter in.”

Does he think he’s coming out of, or mining, a photographic tradition? “I don’t know about a tradition, beyond what, obviously, a lot of people would call it, ‘street photography.’” Root acknowledges that photographing closed bars in the hours before they reopen might certainly be tagged as street photography, but he argues more precisely that his work evokes “the sense of the ‘flâneur.’” I love this, the (essentially) French notion of a person who strolls around in a seemingly random way, as an idler or a loafer. I was happy to hear Root say this, as what I find most appealing about his work is its spiritual alignment with the “walking essay” voiced by a perambulating persona who’s a close observer as they walk, quietly, taking in the city’s ebbs and flows, its dynamism and surprises. Root’s Alfred Kazin with a camera.

Root’s terrain may be wide—or wideish, as he rarely strays past the borders of his East Village ‘hood (“Because I do it on foot. There’s kind of a built in limit to it”)—but his observations are precise. “The unusual light is what drew my attention [to photographing closed bars],” he told me. “And how they took on personalities, and how I saw things that I never saw.”

I mean, I’ve walked by 7B [on Avenue B] for forty years, and I never noticed certain things that I was able to see at 5am in the quiet and in the dark. And with the unusual lighting, you know, where under-counter lighting is left on or bathroom doors left open, all of a sudden it just takes on this other-worldly aspect, and it creates a new environment out of an environment that we’ve seen many times, but when it’s peopled, it’s different. Right?

It’s cool to see lovely shots of some of the watering holes I like to hit when I’m in town, Blue and Gold, Cherry Tavern, 2A, The (old) International, among them. For years I’ve fought my own on-again, off-again romance with drinking in bars. I asked Root if he ever feels the need to resist sentimentalizing taverns (and by extension those who drink in them, for an hour or for eight hours) as he captures them in moody, suggestive light. He makes clear in the book’s introduction that he’s careful not to pass judgements on the folks who wander in and out of bars at all hours. (I spoke to Root for only a short while, but I sensed that this forbearance and tolerance is native to him). Yet he admitted to me that the danger of romanticizing bars is always present. “I hope it doesn't interfere or affect my work,” he said, before adding, “Although it probably does.”

People turn to drugs and alcohol for any number of reasons. And they aren’t necessarily all bad, and they aren’t necessarily all good. And some people will go off the deep end. And with either, my efforts are only to capture the essence of the bar and the life that the bar has. Without people. And what people do with that is kind of a different topic.

Root, who is sixty-five, has been taking photographs for decades. He didn’t mix well with school. “I was one of those people that probably shouldn’t have been in school. But, you know, I went because I thought that was what I was supposed to do.” In the early 1980s, on an ill-fated assignment for a book that never materialized, he wound up on St. Mark’s place shooting photos of Madonna on the set of Desperately Seeking Susan. Sometime later, shooting at the Plaza Cultural community garden in the East Village, he stumbled upon “a little indie band doing a little indie video,” took photos of them in action, and promised the band that if anything turned out well, they could use them. He hustled the photos to the band’s production company, ATI— “at the time like a cheap knockoff of MTV”— and lied to them that he’d been paid for those Madonna photos. He parlayed that fib into genuine and steady work. “I ended up shooting, once a week, all these different rock bands, and people like Robert Plant, Frank Zappa, Marianne Faithful, an amazing kind of list. It kind of just happened, and it happened because I was out doing these self-directed projects. Most of the things that are have happened to me, in a positive way professionally, have been through self directed projects.”

For the photog gear heads among my readers, Root mainly use two cameras on his pre-dawn bar hunts. “One is a Nikon DA 50, which is a DSLR [digital single-lens reflex camera]. And then one is a pocket camera but it’s a really beautiful pocket camera, the Sony RX 105.” Shooting an off-hours joint requires that Root press his camera lens against the window, and the subsequent, stubborn low-light requires that he use “anything and everything” to stabilize that camera. Root has used a nearby railing, even a No Parking sign to balance his camera. (“My wife and I joke that it’s like using the city as a tripod.”) He recommends both cameras. “The Nikon is able to take larger photographs, which then conversely allows you to crop more. And the the Sony [produces] a decent-size image, you know, I think it’s 20 inches or 22 inches at 300 dpi, which is a good resolution.” Root shoots “raw,” a process wherein the RGB, or red, green, and blue, layers are kept apart (as opposed to a typical JPEG). Back home, Root will join those layers as he saves the file, fiddling a bit if necessary. “So the you’re able to change color, temperature, you can bring up the shadows a little bit, you can bring the highlights down, bring the whites up a lot easier.”

Another aspect I find fascinating in New York Bars at Dawn is the eerie, paradoxical presence of people—though there’s no one there. As I page through the book, gazing through Root’s camera as it’s pressed up against a window, it’s impossible not to see patrons materialize in the interiors. Without realizing it I lower a transparency of sorts of drinkers, standing, sitting, laughing, sullen, in groups or solo. Root understands the phenomenon. “The spaces themselves come to life with life,” he explained. “And so the idea of a person in that environment kind of completes the picture.” He mentioned an observation that writer Rosie Schaap (Drinking with Men, Becoming a Sommelier) makes in his book’s foreword. “I thought she captured something when she said that she always thought that when bars were empty, they were devoid of soul, or devoid of life. And she realized on looking at the photographs, how, in fact, they were full of life, it was just a different life, it was a different life than when you know, that then 8pm.”

(On one recent occasion at a site, Root ran into actual people. In his usual pre-dawn hours he was photographing the closed Blue Ruin at Ninth Avenue and 40th Street. “I got myself all set up, I’m taking pictures, and I think, something doesn’t look right. There’s a strange sense of being at that hour. I noticed that the front door’s smashed. And I go to look inside. And the inside door’s smashed. People inside! Oh, boy. And I suddenly realized I was photographing a crime scene.” Root heard the approaching police sirens. “And I kind of backed away slowly.”)

Once in a while, in an attempt to move further beyond the East Village, Root tried his bicycle, but riding couldn’t offer “the same sense of peace as the walking, the pace, the steps.” He added, “The pace that the world comes at me when I walk is calming to me, in addition to just straight up moving. And, you know, you have the benefit of the physical. While you’re [in the city] lugging all your groceries home, wishing you had a car, some of the some of the advantages of being here is that you you’re kind of forced to walk, and walking presents its own world.”

I asked Root if he’s ever felt compelled to photograph other closed places in the city at dawn, such as a bank, which offers its own brand of off-hours ambient lighting. “No,” he said flatly. “There’s no….” He paused. “It doesn't feel like there’s a story there. And also, architecturally, interior design-wise, bars are so different. They’re weird. They’re idiosyncratic. A bank is so cut-and-dry. A CVS is so cut-and-dry.”

There’s just something about bars. Tell me about it. “The life of 5am,” he remarked. “You know, they’re just getting done right at that time. Oftentimes, there’s still people in there. And so they they operate in this kind of nether world of, ‘Is it nighttime?’ ‘Or is it the day before, or the day after?’ And it adds to that question.”

Photographs courtesy of and ©Daniel Root

Great piece, man. I need to get this book!

I found this fascinating Joe, thanks for sharing, it's a great subject to photograph. Something unclear in the interview... It sounded like Root shot a lot of bars from outside looking in... But it also sounds like he got access to quite a few of these bars at 5am, or at least some of the pictures here look like he must have been inside. Can you elaborate?