I’m generally adverse to Christmas music. There are plenty of reasons for this, yet writing about my low tolerance for seasonal music seems annoying, a churlish gesture in this month with no point but to be contrarian. Viva all who crank the Yuletide tunes!

The other night, Amy and I were in the car while choring when on a whim she pulled up a video of “O Holy Night” performed by The Choir of King's College, in Cambridge. It’s her favorite Christmas song, and I love it, too. The song’s history is astonishing. The words were commissioned by a priest (his name lost to history) from a small French town to commemorate the repair of a church organ; he asked a local poet, Placide Cappeau, to write the verse. Cappeau titled his poem “Cantique de Noel.” Inspired, Cappeau asked a friend, the composer Adolphe Adam, to set the poem to music, which Adam completed in 1847. A decade or so later, the American writer John Sullivan Dwight, moved by Cappeau’s words, in particular the lines that resonated with Dwight’s Abolitionist sympathies, adapted to lyrics into English, modifying them slightly. The song, in French and English, in both sacred and secular contexts, has since become a standard.

As supremely lovely as “O Holy Night” is, the song has been dinged by some unruly controversies down the decades, facts—and rumors—that illustrate how words and music can bear fingerprints of those wishing to celebrate as well as those wishing to condemn. Cappeau eventually split from the Catholic Church and drifted toward agnosticism, opposing slavery and other discrimination, and adopting socialist beliefs. And not long after the song became popular in France, rumors began circulating that the composer Adam was Jewish. Like anti-Semitism in any form, this contention metamorphosed into certainty and dogma for those who needed it to be true, and overshadowed the song’s organic, formal beauty, intentionally befouled by those who view the world through bigotry. (In the face of such rumors, the French Catholic church leaders decided that “Cantique de Noel” was “unfit for church services because of its lack of musical taste and ‘total absence of the spirit of religion’.”) Adam’s Jewishness has never been conclusively proven—his religious/cultural identity moves within that unseemly space where truth and fanaticism eternally collide—though, predictably, he’s to this day wholly “claimed” by groups that depend on ideology.

None of this fascinating history was available to me in the car. I’ve learned of it only recently. As I listened the other night, moved again by the breathtaking melody in service to enchanting sentiment, the world around me subtly shifted, as it does when I’m listening to music that stirs me. The shitty strip malls, the harsh streetlights, the dark that overwhelms the Midwest with tyranny—all of it softened, as if for six minutes the world’s lens shifted benevolently to soft-focus. By the end of the song I was in tears, moved as much by my bah-humbug recognition of the song’s exalted hymn to devotion, a devotion that I lack, as by the melody’s complex beauty and its hushed, sublime rendering by the boys in the King’s Choir. “O Holy Night” elevated Amy and me in our car in the Target parking lot, with its soaring movements and octave leaps, its formal difficulties mastered so poignantly by these young boys, the very image and sound of innocence. If only for a brief moment, I felt as eternal in those moments in my car as those boys were in King’s College Chapel, halfway around the world singing a hymn a century and a half old, a hymn that humans will likely be singing for as long as there is a world to praise.

Yet there was something else working through me in those moments, as lifting to the surface of “O Holy Night” was another song, wildly different in origin yet kindred spirit.

In the summer of 1979, Paul McCartney was in transition. The latest (and in the event, the last) Wings album, Back to the Egg, was released on June 8, and amidst promoting that album and and planning for a fall UK Wings tour, McCartney, always restless, had begun fooling around on keyboards at his small home in remote Scotland and his country residence in Sussex. Noodling around, McCartney moved among trivial, “New Wave”-sounding ditties, requisite ballads, and tech-sound experiments, uninterested in producing “releasable” product at this point, simply going where his new keyboards took him.

One afternoon, as related in Keith Badman’s The Beatles—The Dream is Over: Off The Record 2, McCartney began work on an instrumental. “I had heard a piece of music that I liked, which was a very classical sounding piece,” McCartney remarked.

So, that day, when I went into the studio, I thought it would be a nice change if I tried something, sort of, classical. I built it up…so it does sound like something classical-cum-something else.

In his untutored Northernness, McCartney either didn’t know the “piece of music” that he liked, or couldn’t have been bothered to discover what it was. Characteristically, he floated on top of the memory of the piece and drifted home, settling in front of an instrument and, trusting his sublime gifts of melody and form, assembled his song in response.

The tune sat in a pile with the the other tracks that McCartney had created that summer. In the fall, now with an eye toward releasing them in some form, he felt that the tune needed proper lyrics. He sketched some simple lullaby words—

Someone’s sleeping

Through a bad dream

Tomorrow it will be over

For the world will soon be waking

To a summer’s day

—overdubbed a vocal, and mixed the now completed song at his Replica Studio, in London.

“Summer’s Day Song” appeared on McCartney II (1980) and is time-honored Macca, a lovely, richly melodic, superbly sung ode to summer and all that we associate with it. I’m sure that there are plenty of folk—anyway those who lack the sweet tooth for McCartney’s ballads—who’d call the song a trifle, feather-light. Yet I hear something in the song that’s profound: pure gratitude, which is never shallow, something I learn more and more as I get older. The song’s in love with and thankful for the world, as so many of McCartney’s songs are, sung by a man knocked out by what a sunrise and stray musical notes in the air can do.

And this, I think, is what I heard in the background as I listened to “O Holy Night” in my car. I turned to Amy at one point and remarked that, listening to the song, I could imagine, maybe even understand, how one can argue that Cappeau’s faith in God is what inspired and allowed him to reach, and to exalt and to mirror in song, the grandeur and mystery of the divine. (I didn’t know then that Cappeau was only mildly devout, and would eventually leave his faith behind.) But as I heard, or anyway felt, unbidden strains of “Summer’s Day Song” play in my imagination, the parallels were striking, and moving: both songs, one sacred, one secular, are in praise of something larger than the songwriters. Certainly McCartney’s melody, though pretty, doesn’t approach the transcendence of Adams’s. Beyond that, I hear very little difference between “O Holy Night” and “Summer’s Day Song.” I hear kinship.

Cappeau writes, “For yonder breaks a new and glorious morn”; McCartney, “For the world will soon be waking to a summer’s day.” Cappeau proclaims that “oppression shall cease,” McCartney that a bad dream will be over tomorrow. Cappeau wrote in praise of a Christian God, McCartney partly under the influence of his musical deity Brian Wilson. Both songs hum with praise for the eternal gifts that the universe vouchsafes us in our darkest hours. Obscure the compositional origins of each song, and what becomes clear is the sacredness with which each is in touch.

On a visit to my parents in Maryland for the holidays last week, I experienced another surprise into gratitude. My mom and dad moved to a retirement community about a decade ago. My mom has been singing in the community’s women’s chorus, the GraceNotes, for nearly as long. For many years my mom sang in the choir at Saint Andrew’s Apostle Church when I was growing up. I hadn’t heard her sing in decades.

Amy and I and two of my brothers met at the chapel for the Winter concert. My mom stood in the back row of the riser, one of among thirty or so seniors, as the chorus sang a modest selection of seasonal sacred songs, including a Hebrew song (in English), and a few “crowd-pleasing” secular numbers, a goof on “Twelve Days of Christmas,” a “rock and roll number,” and the like. The women sang very well. The program was wonderful. We attendees all sang a few holiday standards before the concert began, so we were in a festive mood.

There was a number in the program that I’d never heard before, “The Falling Snow” by Earlene Rentz. I’m not fully comfortable being in churches anymore, self-conscious in my decades-long agnosticism and the unresolved feelings that it generates, but I was taken out of myself during “The Falling Snow,” a simple, devastatingly beautiful song extolling the beauty of the natural world. The melody is set in a minor key, the intervals narrow enough so as not to pose much of a challenge to an amateur, aspirant singer, and the lyrics are plain yet evocative. I found myself gently moving, as if under a pleasing trance, as the women sang. Caught in—and surprised by—a spell of sorts, I began to see these women through various stages of their lives: as young girls squealing in snowfall; as young women in college, darting down the halls of their dormitories; as married women; as single women; with families, without….

I’m not sure what produced these imagined narratives—the song’s elemental prettiness, I guess, and the touching scene of women in their 70s, 80s, and 90s gathered together in a room, all of their personal and private pasts commingling. (Amazingly, afterward Amy, who was moved to tears by the end of the song as I was, admitted that she’d too helplessly imagined scenes from these women’s lives as they sang.) All of us in that room, I believe, were touched and united by something that I can only describe as sacred, spirituality less inspired by the chapel setting than by the presence of voices in unison singing a simple song about the world’s reviving charms. Anyone, anywhere—a raw, spiritually conflicted poet in a French village, an accomplished secular pop composer in the UK countryside—can be in touch with divinity when the song takes us.

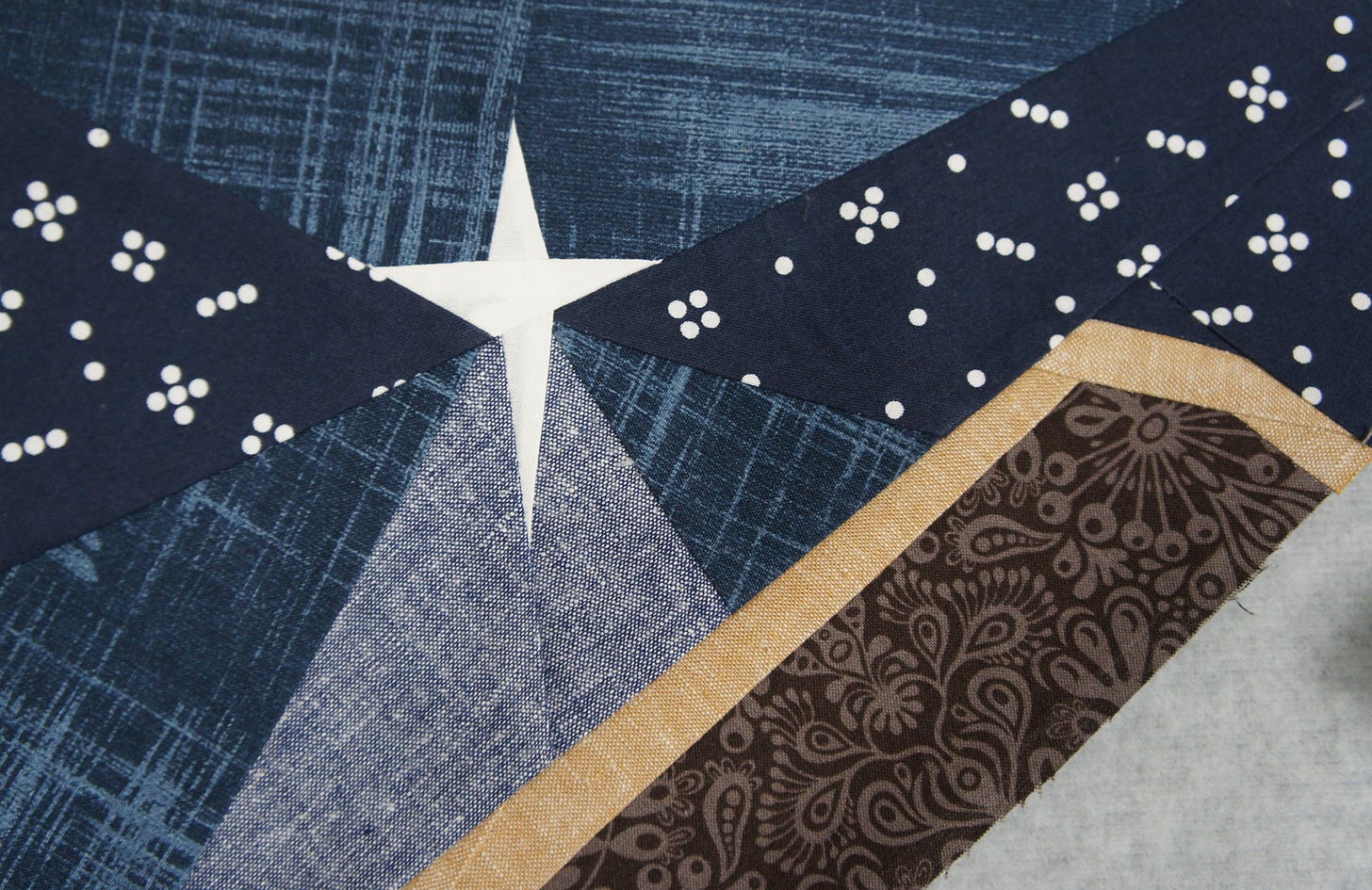

Featured image “O Holy Night—Paper Pieced Nativity” via Angela

Thank you for this post, Joe. "Anyone, anywhere... can be in touch with divinity when the song takes us." In the shared spirit of the season: at a friend's invitation, my husband and I attended a Methodist service on Christmas Eve, with Christmas hymns performed by a 12-voice choir and a bell choir. I found myself weeping throughout. I'm a lapsed Catholic, but sacred choral music (my 91 y.o. father is a retired choral director) performed in a church gets me every time. Peace to you.