"But finally, I suppose, the most difficult (and most rewarding) thing in my life has been the fact that I was born a Negro and was forced, therefore, to effect some kind of truce with this reality."

So wrote James Baldwin in 1955, in “Autobiographical Notes," adding, in parentheses, "Truce, by the way, is the best one can hope for."

Chuck Berry was iconoclastic, preternaturally gifted, and fiercely driven. So large, he feels, six years after his death, like a fictional character. "The Originator," some figure from mythology.

The writer RJ Smith, then, faced quite a task. How to bring alive someone who to the average reader is more likeness than man? A doubled task: he's telling the story of a man in a time and for a culture that's growing impatient with the grossness behind the artist. Chuck Berry was an asshole, particularly in his final decades. Well-documented and well-known incidents and accusations abound of deplorable behavior set against the great music. It helps that Smith has great affection for his subject, warts and all. Faced with the task of presenting a dimensional Berry, Smith wisely avoids a hagiographic, defensive airbrushing of Berry's character, as well as a pious condemnation of it. Simply: Smith reports, from a distance, wryly dramatizing Berry as a gifted, flawed, nonetheless engrossing character, the kind of person we find compelling in a novel or in a prestige drama.

In some ways Chuck Berry: An American Life is a difficult book to review. While writing I feel as if I'm recreating a lively conversation I had with someone on a long night, affectionately recalling the talking points the next morning, still smiling at his bright, witty turns of phrase. Smith's writing ebbs and flows on currents of talk, moving from insight to insight, sometimes surprisingly, the connections implied rather than stated. By the end, Chuck Berry is a necessary, powerful, often moving look at an important American artist, and is clearly now the standard bearer of Berry biographies.

Chuck Berry is a story about music and race, form indivisible from content. It could not have been about anything else. As with many biographies about (and autobiographies from) wildly successful artists, the tension produced in the opening chapters, where the subjects struggle to identify themselves and to be identified, moving hungrily from one long-odds shot to the next, slackens in the final third, as the subjects' risks are often smaller, less charged, and usually less interesting. Yet the essential struggle for Berry—that of living a life of liberty on his own terms as a Black man—never goes away, it only softens at the edges, mutates into something arguably less offensive as the fame and the money arrive.

Berry never stopped working. In this supremely well-researched book, Smith recounts gig after gig spanning the globe, well into Berry's late years, a careerist drive in part planted by his hard-working father, and in part native to Berry anyway. He felt that he had many things to prove to many people, to his numerous backing bands, his label, his fans, women. He never ceased enacting out those demands, and Smith follows these impulses from Berry's adolescence through his fame, foregrounding Berry's motivations against a background of strife, from segregation and Jim Crow to Black Lives Matter. Berry's struggles to define himself, at times arrogantly, against popular culture even as he was embraced by that culture is the book's true subject.

The songs and the recording sessions are, of course, also here, nearly always explored as reactions on Berry's part to the complex world around him, a world to which he wanted—demanded—full access. Hence his famous songs about moving, going, and arriving on the singer's own terms, half grinning as he plays. Smith's takes on the cultural importance of a Black man driving, and being seen in, a Cadillac are informed and powerful, and add dimension to Berry's songs the way great criticism should. To Berry, the long road offers much and promises little to a Black person who dares to steer his own car forward.

Three passages about three seminal Berry tunes—"Let It Rock," "Promised Land," and "Rock and Roll Music"—illustrate Smith's intelligent and sensitive takes on Berry's music, on its daringness and uniqueness, clear and profound thinking that is characteristic of the book:

From the start, "Promised Land" feels tossed off, musically and lyrically, and that’s a big part of its power. It arrives like another Chuck Berry road song and rings with artless sincerity, a friendly character eager to tell his story. It could be a superior version of “Route 66,” a road trip full of place names and featuring one fresh plot device—a mob in the rearview mirror.

...

“Let It Rock"... [is] rock & roll if anything is, not to mention A People’s History of the United States with [pianist] Johnnie Johnson accompaniment.

...

A funny thing happens in the last verse of "Rock and Roll Music.” Berry sings, “It's way too early for the congo, so keep a rockin’ that piano.” What’s that about? He probably means to say too early for a conga. That dance step fits with the mambo and tango he’s mentioned, and it's too early to go dancing because it’s not night yet. But Chuck Berry doesn’t make many mistakes with his words, and if he chose to say congo instead of conga, it has meaning.

Smith goes on to mention "the place called Congo Square, which Berry might even have seen when he traveled through New Orleans the year before and again about a month before he recorded 'Rock and Roll Music'," observing that "the conga drum was played there, in the one space in New Orleans where enslaved people could play drums on Sunday."

The conga that comes from the Congo. A oneness, then, among the sound and place. All of which underscores how “Rock and Roll Music” steers the music forward and backward in time. This will be something you will want to be a part of, he begins by cheering. Then he says: this backbeat is ancient, and lived long before Elvis Presley.

I hear Berry take on discrimination in "It's My Own Business," his drolly-sung single from 1965 (it also appeared on his album Fresh Berry's). By this point Berry was revered not only by his normal faithful but by fans with names like Lennon, Dylan, and Jagger. He was worldwide-present. And yet: "I am tired of you telling me what I ought to do / Stickin' your nose in my business and it don't concern you." And that's the opening line. The rest of the lyric reads as thinly veiled autobiography, especially after Smith's book. Just beyond the rim of the spinning 45 are the white supremacist know-it-alls ("Seems like the ones that want to tell you / They don't ever know as much as you"), the cultural snobs ("If I go buy a Cadillac convertible coupe / And all I got at home to eat is just onion soup / It's my own business"), the pious ("After workin' on my job and then drawin' my pay / If I want to go out and have a ball and throw it all away / It's my own business"). And authority at large: because the singer's "not a juvenile," he can "go out at my own free will,"

'Cause I don't wait until tomorrow

To do something I could do today

For Berry, authority at large came in one color.

I'm not suggesting here that Smith sacrifices the ecstasy of Berry's music for cultural analysis. The songs are here, their magic and their thrills evoked. Smith has great ears, a fan's set of ears, and he gets, and gets at, the shifting dynamics of song-making, the transparencies that musicians in the same room lay on top of what each other's playing, the semi-nods to all around acknowledging that what they've got going is good, maybe even new. Smith's especially well-tuned to pianist Johnnie Johnson, bassist Willie Dixon, drummer Ebby Hardy, and the other musicians crucial to Berry's early and ascendent sound. (Happily, Smith keeps the long overdue Johnnie Johnson revival going with this book. His writing about him is warm and respectful.) His portrait of Berry is of an artist who forged new paths and followed those paths into a life imagined but not articulated by the millions of fans who, delighted to be there, followed their hero up those trails. He got there via rock and roll. Here's Smith on the early stirrings:

Extraordinary to think of the voodoo that happened when folks heard an electric guitar with their feet for the first time, flooding their spines, connecting them to every other spine in the barn. Extraordinary, as well, to think about a human strong enough to invoke that state again and again, hundreds of times a year. It was a form of play from the start, your hands opening up spaces that radiated a shocking form of love, of wildness, lawlessness within community. It was better than work, harder than work. Not work.

Great stuff. His account of Berry showing up unannounced at Circle Jerks gig to play is perhaps my favorite passage in the book, a moving illustration of the profound generational influence Berry had (and has) and of Berry's eternal love for plugging in and playing the guitar onstage, not to mention getting off on screwing around with whatever band had the courage to back him. The unlikely Circle Jerks had no choice that night at the Mississippi Nights club, and their punk energy and plucky attitude floored Berry, improbably, who made it known to the band, in his style, that they were one of the best he'd ever witnessed. He didn't need to say that to them.

But what of the Mann Act, the years in prison, the "toilet sex" tapes, the decades of infidelities, the unauthorized photos of sexual debauchery, much of it mean-spirited on Berry's part? Smith reports it all, does not defend any of it, adds the material to Berry's outsized strangeness and stubbornness. He documents the protests at Berry's funeral. Leaning in at the margins is the feeling that, whatever Berry's compulsions, sexism, and nastiness, his life was simply tougher to live out than others', a burden less to do with the intrusions of fame than with the daily, deadening drumbeat of racism, which from the onset put Berry at odds with living the kind of liberal, indulgent life that it was his desire—his choice—to live. "Racism and sexual freedom fused," Smith observes of Berry, "moving with him wherever he played." There's no forgiveness on Smith's part for what Berry delicately called his "peccadilloes," but then I don't think that Smith feels his biography is the place for pardoning anyway. "What we have is more interesting," he writes near the end.

A choice of threading through the details of his life or working around them completely—your call!—and simply hearing him. To pull the joy and poetry out of the music he created and have it take us where it wants to go—not where he went. To live our lives with it, and not live his life. That's a lot.

James Baldwin also wrote, "This is the only real concern of the artist, to recreate out of this disorder of life that order which is art." Berry's fierce focus was on his bottom-line, his guaranteed pre-show bags of cash, on not asking permission to take what he wanted, what he knew was his, what his art gave him. His American life. Berry smoothed the sharp edges of disorder, the unruly elbows it threw, into promises of movement and purpose for as overwhelmingly white audience for whom the roads were always far more hospitable. "Everything I wrote about wasn't about me, but about the people listening," he told an interviewer. Yet, always there—noxiously in his early life, implied in some of the songs, veiled but not vanquished by his fame and fortune—was racism.

At one point Smith describes Berry as "Rock 'n’ roll’s Black best friend," a pretty brilliant summation of the place Berry found himself as other white artists cashed in on his material. "The Beatles and Stones placed his songs with young listeners and then poured out their gratitude in interviews," Smith writes. "How did it it feel, he would be asked over and over in the years to come, to have the Beatles play your songs? There was an expectation from white interviewers that he would be publicly grateful for the acknowledgement. He had worked for years to distinguish himself against all others and perhaps now it was starting to seem that he had lost the distinction, that he was a barely seen content producer enabling others to express themselves."

Chuck Berry outlived rock & roll, Smith argues, and he now seems "less like a rocker and more than ever simply a representative American artist. He had a vision of a country that did not exist, and he willed it into life. A place where anybody might want to live."

His reward? "A day pass and a warning that it was best he not hang around after sundown."

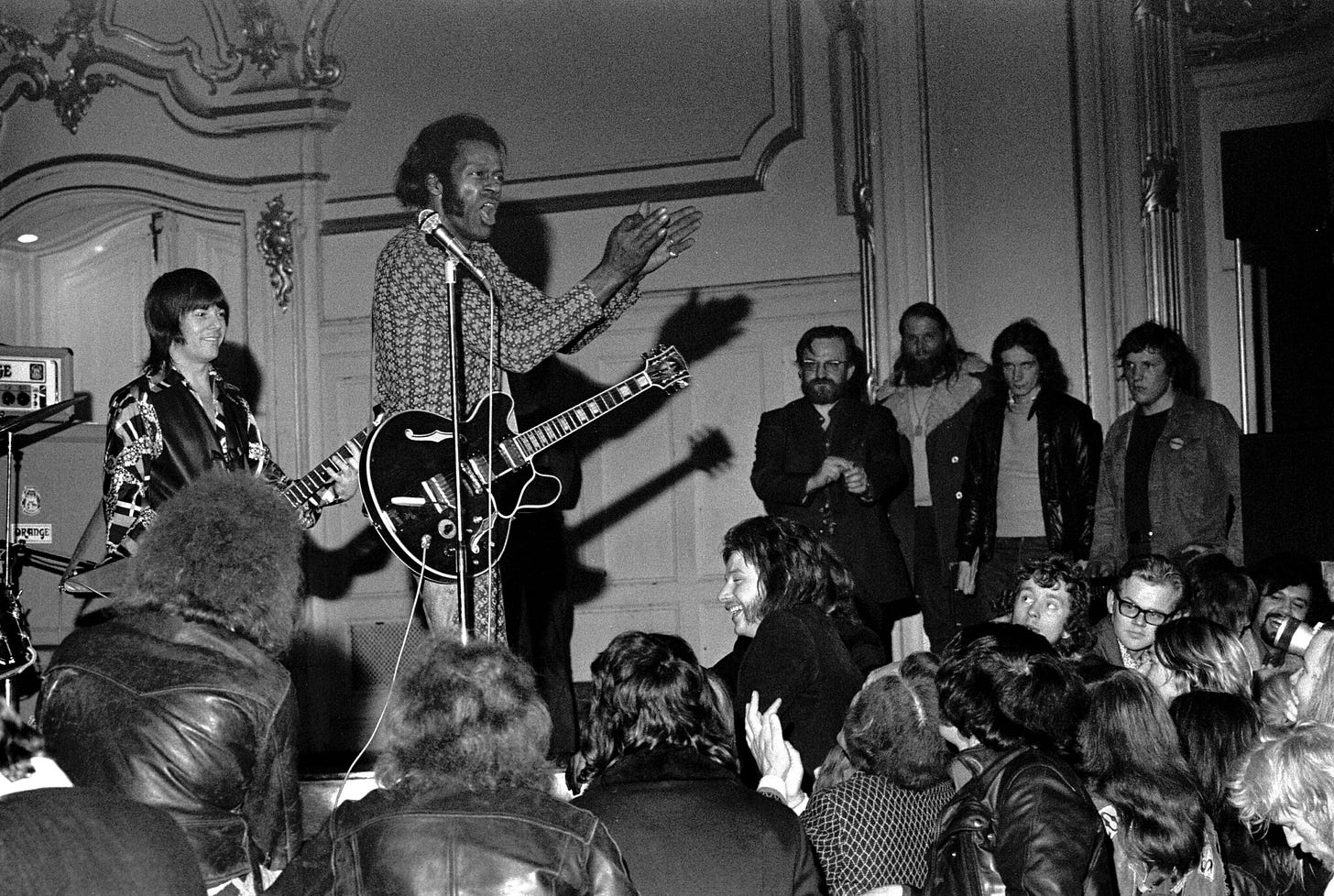

Photo of Smith by Madeleine Burman-Smith / Courtesy of Hachette; photo of Chuck Berry, January 1973, Musikhalle Hamburg, Heinrich Klaffs via Flickr