The song's too simple

Some thoughts on art critic Dave Hickey and rock and roll

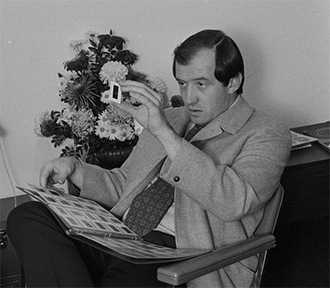

In 1985, Dave Hickey published an essay titled “The Delicacy of Rock-and-Roll” in Art Issues magazine, and later included it in his book Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy. In the piece, Hickey, loosely and casually yet highly persuasively, takes down the so-called dichotomy between high and low art. It was a career-long game for him, to deflate pompous arguments.

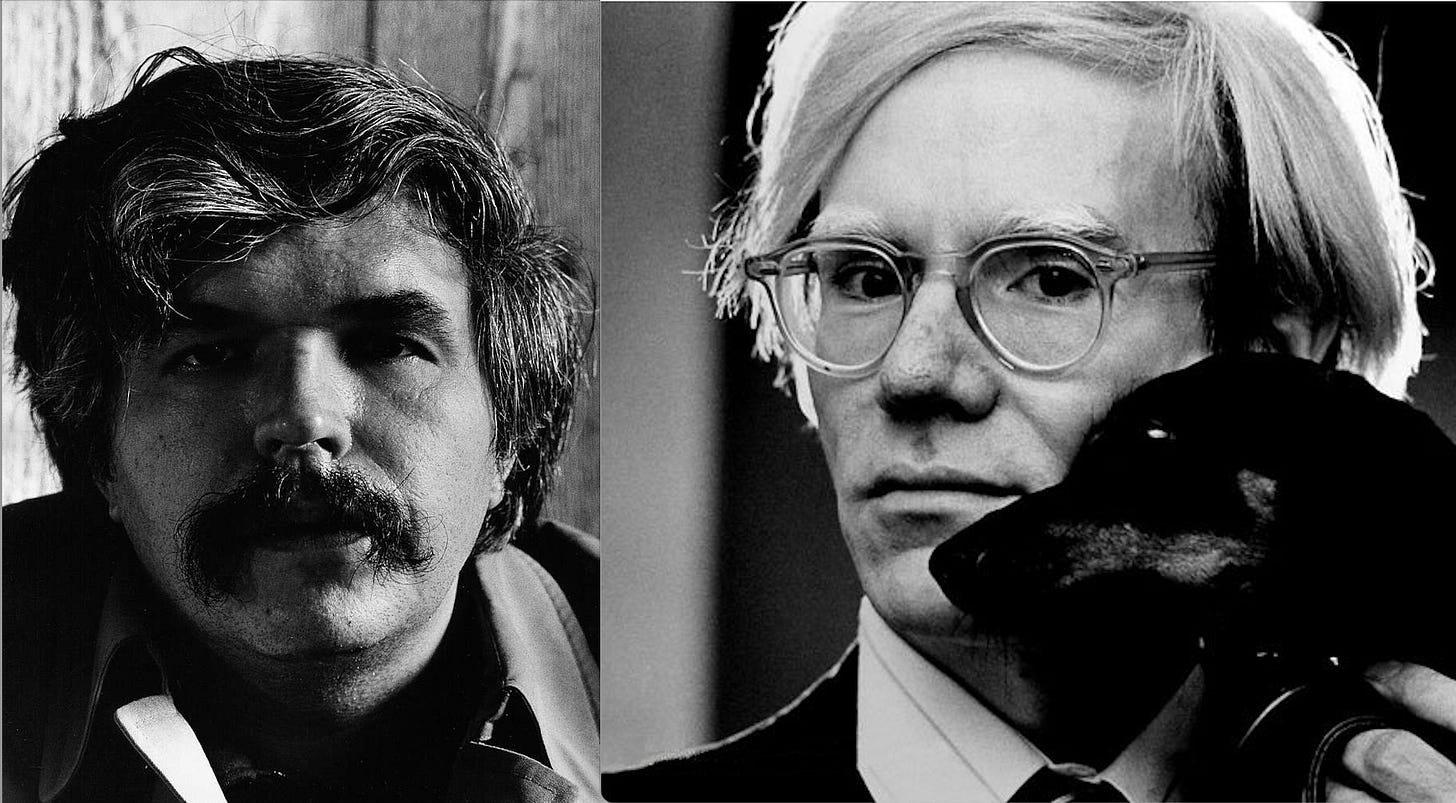

In the essay, Hickey remembers a night at an underground film festival at University of Texas, in Austin, where he was a student in the mid 1960s. That evening, works by the experimental filmmakers Stan Brakhage and Andy Warhol were screened. To Hickey, a rowdy, sex-crazed kid steeped in “radical politics, jazz, rock and roll, and linguistics,” Brakhage’s film was indulgent and pretentious in its arch, meta insistence on kinetic action and deliberate quick-editing, whereas Warhol’s—an agonizingly long six minute study of a man sitting in a chair getting a haircut—was stupendous precisely because it was challengingly, riotously dull, and, thus, hilarious. Near the end of the film, the guy in the chair casually reaches for a Lucky Strike and lights it, and the crowd of college kids hooted. Some action, finally, they roared, in on the joke. “Warhol’s self-inhibiting strategies liberated him as an artist,” Hickey marveled, “and liberated his beholders, as well, into an essentially comic universe.”

A couple of decades later, fairer to Brakhage but still charged by that night, Hickey describes the screenings as nothing less than “the end of the Age of Jazz and the beginning of the Age of Rock-and-Roll.” Unconvinced that jazz musicians—“the four of us,” as he imagines it—play purely free, as there is always one musician holding “onto the wire” while the other two or three musicians are allowed to roam and to improvise, he instead feels liberty in rock and roll, which, on the other hand,

presumes that the four of us—as damaged and anti-social as we are—might possibly get it to-fucking-gether, man, and play this simple song. And play it right, okay? Just this once, in tune and on the beat. But we can’t. The song’s too simple, and we’re too complicated and too excited. We try like hell, but the guitars distort, the intonation bends, and the beat just moves, imperceptibly, against our formal expectations. Whether we want it to or not, just because we’re breathing, man. Thus, in the process of trying to play this very simple song together, we create this hurricane of noise, this infinitely complicated, fractal filigree of delicate distinctions.

A great working definition of rock and roll. “We’re all a bunch of flakes,” Hickey adds with glee. “And that’s something you can depend on.”

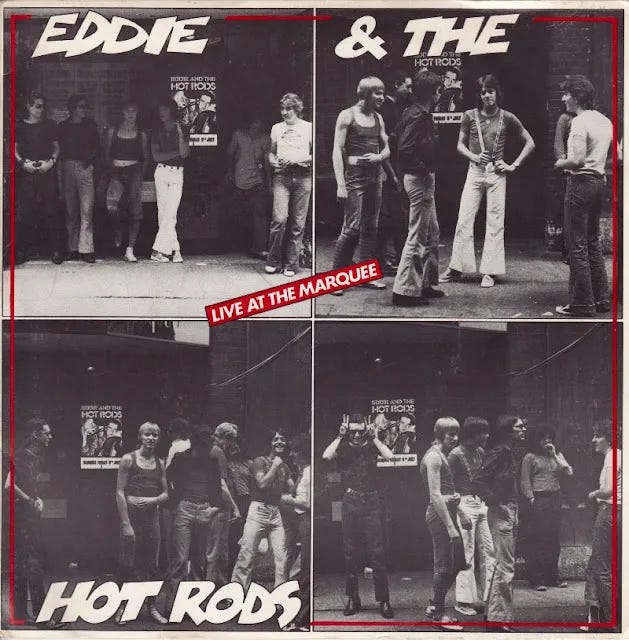

You could also depend on Eddie and the Hot Rods, a terrific band that never quite received their due. Usually categorized as a pub rock outfit, they made a handful of great records. Their EP Live at The Marquee was released on Island Records in July of 1976—it’s a great-sounding mobile recording of a July 9th show—as the U.K. punk scene was roiling.

We didn’t need another version of Them’s “Gloria” like we need, say, food and shelter but sometimes a cover song can feel just as sturdy and vital. Eddie and the Hot Rods’ version segues into “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” another performance that we didn’t know we needed, along the way vibing off of the same barreling energy that the Sex Pistols let loose when, snarling, they attacked and upended the Monkees’ “(I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone” a little while later. Earlier that year, the Pistols opened for the Hot Rods at the Marquee and smashed up the joint, and also the Hot Rods’ gear; later in the summer, the Hot Rods would alternate ear-ringing slots at the club with a young and hungry AC/DC.

The performance on this night begins before the song starts, when one of my favorite rock and roll moments occurs: singer Barrie Masters, peering into the dark in front of the stage, senses that something’s not quite right, and then he gets downright dismissive. “Move all these chairs,” he bellows, suddenly enraged, “don’t want ‘em in ‘ere! Get up, move ‘em all.” And if he hadn’t made himself clear: “Can’t have chairs in the audience, they get in the way. Get ‘em out of here!!”

The front of the room duly cleared for dancing, pogo-ing, and general slamming around, the band charges into “Gloria.” It’s a fantastic moment, and sounds epochal, practically historic: in eight seconds, one era ends as another begins. That’s as long as it takes. It feels that way on this night, anyway.

Listen to Masters—with Dave Higgs on guitar, Paul Gray on bass, Lew Lewis on harmonica, and Steve Nicol on drums, churning excitedly behind him—as he hollers “No satisfaction!” over and over as the song ends. If you close your eyes against the fashions you can hear just how close he is to Johnny Rotten’s heralding of “No Future!”, one transparency laid over another.

The Stones roughed up. Pub Rock. Punk Rock. Rock and Roll. The tyranny of taxonomy. What’s in a name? Move those chairs and turn it up.

And here’s Dave Hickey again: “You can thank the wanking eighties, if you wish, and digital sequencers, too, for proving to everyone that technologically ‘perfect’ rock—like ‘free’ jazz—sucks rockets.” Why? “Because, order sucks.”

I mean, look at the Stones. Keith Richards is always on top of the beat, and Bill Wyman, until he quit, was always behind it, because Richards is leading the band and Charlie Watts is listening to him and Wyman is listening to Watts. So the beat is sliding on those tiny neural lapses, not so you can tell, of course, but so you can feel it in your stomach. And the intonation is wavering, too, with the pulse in the finger on the amplified string. This is the delicacy of rock-and-roll, the bodily rhetoric of tiny increments, necessary imperfections, and contingent community

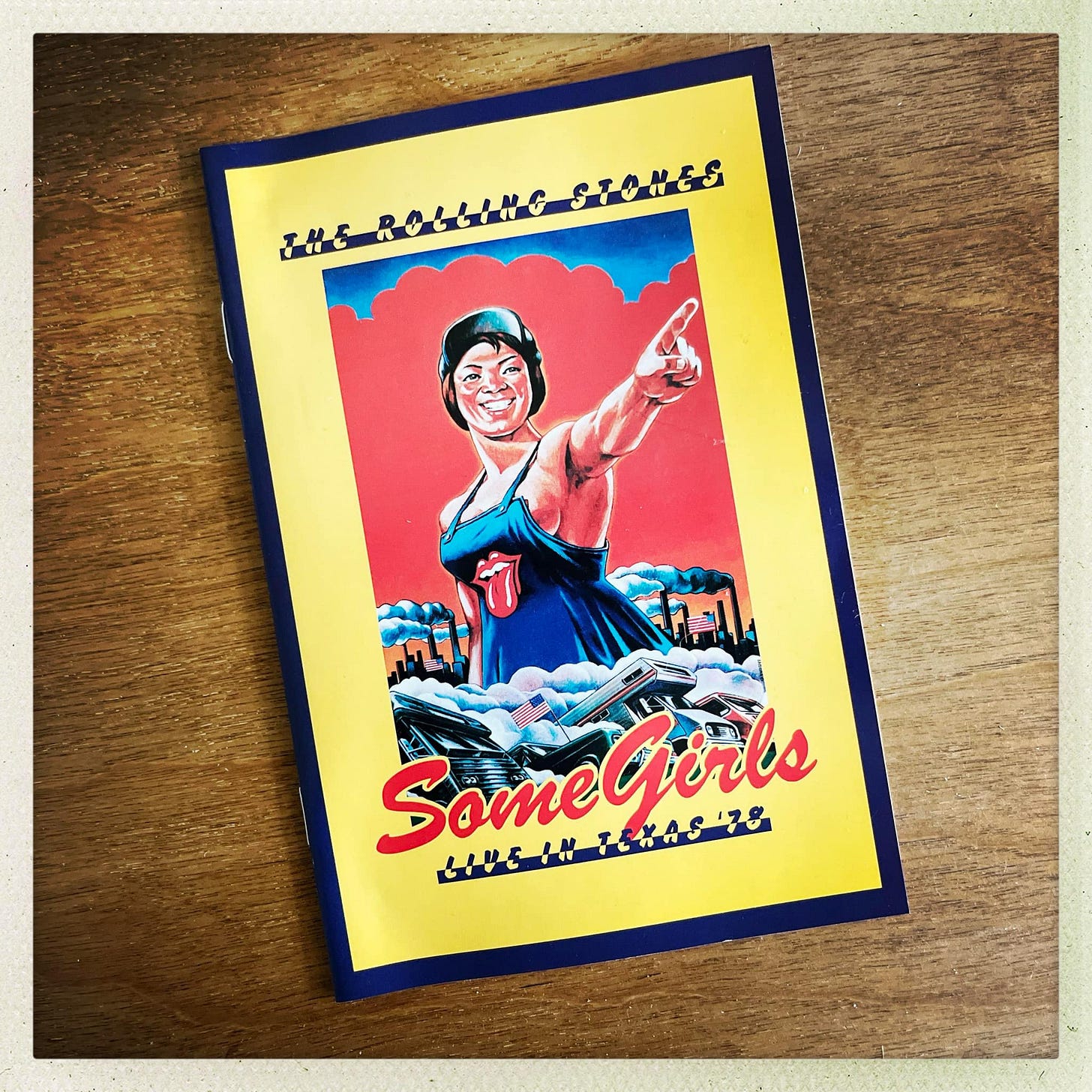

On July 6, 1978, a couple of years after the Hot Rods renewed a tired complaint and roughly a decade after Hickey saw the light down in Texas, the Rolling Stones played the Masonic Temple, in Detroit, in the middle of their brief twenty-five date tour supporting Some Girls. (If you haven’t yet, check out Chet Flippo’s terrific It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll: My On-the-Road Adventures with the Rolling Stones, his fly-on-the-wall account of the Stones’ mid- and late-70s era.) The tour was famous for its stripped down set and infamous for its ragged playing, captured warts and all on the Some Girls: Live In Texas ‘78 album and tour DVD, released in 2012.

I’ve always been a bit skeptical of the notion that that the Stones’ particularly sloppy, particularly loose playing on this tour, as well as the renewed gusto on Some Girls, were “inspired by punk rock,” as goes the standard line. Mick Jagger has gone back and forth about the punk influence on the album, rightly pointing out its disco, country, and blues elements, as well, sources which were more widely revealed in the outtakes and remakes included in Some Girls Deluxe Edition released in 2011. Ever-curious, Jagger in the late-70s was aware of Punk and New Wave, both musically and culturally, and was always anxious that his band appear relevant. But there was a lot of amphetamine playing in that era.

Keith Richards and Ron Wood have been more direct about it. Richards acknowledged in 2011 that in making Some Girls, the band “felt an enormous kick from the punks. There suddenly was this other generation coming on and they couldn't play for [anything] but they were kicking [butt].” He added that the Stones “had been cruising before that, I think.… Not that I'm a really big punk fan, but their energy—and the fact that you realize another generation was coming up on top of you—was a kick up the ass. It felt time to get down to the nuts and bolts of it and not play around with glamorous female voices and horns and stuff.” “Those punk songs [on Some Girls] were our message to those boys,” Wood remarked in 2003. “We never sat around talking about punk, but you couldn't avoid it.”

Anyway, the Stones in 1978 were certainly riding those currents, and whatever the inspiration, the band’s takes onstage of “When The Whip Comes Down” were uniformly ferocious. (Dig this video from the July 18 show, in Fort Worth, Texas.) They released the Detroit version in 1981 on the hilariously titled, contract-fulfilling Sucking In The Seventies compilation. Thickened by Jagger on rhythm guitar, the sound is muscular and dangerous-sounding, and the band plays with an abandon that nearly careens out of control—the impression is of Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman barely holding down the flaps of a tent in a storm. Jagger sounds positively unhinged (though he’s still copping that affected “Black” voice that he adopted in the middle of the decade), and Richards and Wood swap razor blades, chopping angrily at their chords. And though I’ve listened to this version hundreds of times, it still feels as if three of the five musicians remember that the bridge is coming about a bar and half before it does.

Dave Hickey’s observation that “The song’s too simple, and we’re too complicated and too excited” ought to be stamped in the runouts of a thousand rock and roll records.

I’ll give the last word to the esteemed music and art theorist Charlie Watts. In a passage in It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll, Flippo asks Watts about so-called “progressive rock.”

“I don’t think it’s possible,” Charlie said. “Rock swings with a heavy backbeat and it’s done that for twenty-five years. It’s supposed to be fun and that’s why I like it. It’s dance music. But it hasn’t really progressed musically. Progression was Miles Davis playing modals. You can’t do that in rock. Progression was Coltrane, but you can’t do that in rock…. None of this New Wave is new. Elvis Costello is no different than anything else. No one’s really done anything new in rock, now have they?”

A bit later, Charlie asked Flippo how he can possibly write about rock and roll. “It’s silly,” Watts said. “It’s supposed to be fun. How can you do that?”

“Well,” Flippo said, “the only alternatives are politics or gossip.”

Charlie nodded sagely. “I see what you mean.”

See also:

It's all right every time

Music’s like the weather. Some days you don’t notice it. Overplayed songs feel like that. You don’t pay attention to them anymore, or the songs don’t seize you the way they once did.

"Shake Some Action" vs. "Shake Some Action"

After I first heard the magic of the Flamin' Groovies' "Shake Some Action" (on the late, lamented WHFS 102.3 FM out of Bethesda, Maryland) I embarked on a years-long, semi-obsessed quest to find the song. In the mid-1980s, if your local record stores (plural—it was still the Golden Age) didn't have the record and if the record was out of print, you were…

Are you sure that you're living free?

“People look at me like I am a hooker / But I just wanna be a venue booker.”

Images of Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, and Dave Hickey via Wikipedia/Fair Use and Public Domain

Eddie and the Hot Rods sleeve pic via 45cat

That quote from Hickey about how the Stones operate is part of my brain matter. Whenever I hear the Stones, I think of Keith, Bill, Charlie operating in milliseconds of attention. Also: when I got my late career M.A. from NYU in 1999, Air Guitar was one of the texts. Professor Christgau was a major Hickey advocate. In turn, teaching criticism at St. John’s U. In Queens in the two thousand and teens, used Hickey’s Pirates and Farmers as a reference text. And also, Joe, I totally buy your album of Stones covers, some of which I haven’t heard. Finally, their best B-side for personal reasons is “Congratulations,” circa 1964.

That is fantastic. I love all of the quotes that you've included, and suit the topic.

The final comment about, "'I don’t think it’s possible,' Charlie said. 'Rock swings with a heavy backbeat and it’s done that for twenty-five years. It’s supposed to be fun and that’s why I like it. It’s dance music. But it hasn’t really progressed musically.'"

Makes me think of this line that I saw in a review (for a CD which I ended up not getting) which also talks about the tension between musical experimentation in a musical genre which is designed to fit a certain social function: https://www.mustrad.org.uk/reviews/m_hayes.htm

"The problem is that Irish music doesn’t work like the music of India, or West Africa, or Greenwich Village. The melodies are too formulaic. The idiom is structurally and rhythmically too circumscribed by its function as dance music to afford the musician much room for improvisation. A little rumination on that point may be in order, for jazz was also a dance music once and it functioned in ways not very different from Irish music. In the 1940s a number of musicians, Miles Davis among them, broke out of the then prevalent chordal limitations of the idiom and turned it from extrovert dance music into cerebral art. If Charlie Parker and Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie could do that with jazz, why can't Eileen Ivers and Seamus Egan and Martin O’Connor and Martin Hayes not do the same with Irish music?

Well, the only ingredients which the moulders of modern jazz inherited from earlier forms were rhythm and swing, and a system of improvisation built around the notion of chord progression. Jazz is quite simply not constrained by inbuilt structures in the way that Irish music is. ... The musician who wishes to break out of the cage of Irish music has to find his own key. He has to find it within the melodies and rhythms of his inherited tradition. That is what Martin Hayes appears to have done and that is why this disc eventually won me over."