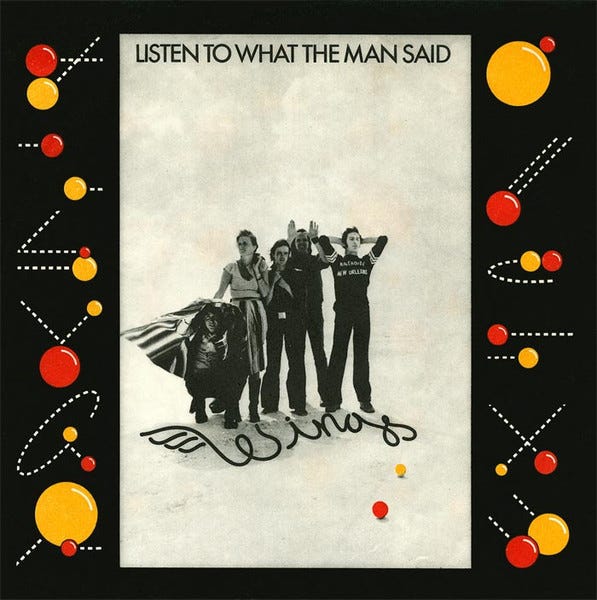

Few songs bring me back to my childhood as powerfully as Wings' "Listen To What The Man Said," released as a single in 1975. Such an effortless sounding song had to labor a bit, as it turns out: the tune would come alive when Paul McCartney played it on piano for others to hear, yet the ideal group take remained stubbornly elusive at Sea-Saint Recording Studio, in New Orleans. Eventually, with sweetening by Traffic guitarist Dave Mason and a sublime saxophone solo from L.A. Express' Tom Scott, the band perfected a bright, gently rocking arrangement, buoyant on its own cheery confidence. Pop sweetness has a long expiration date, but the band ended up using the first take, rightly sensing magic in the performance.

Here's what I feel about the song nearly half a century later:

If I stare too long as "Listen To What The Man Said" plays I might burn my retina.

Regular exposure to "Listen To What The Man Said" might cure someone of Seasonal Affective Disorder.

Roy Carr and Tony Tyler once described the song as "High Pop." I hear "High Sun."

"Listen To What The Man Said" was a number one hit on Billboard and was all over the radio through the summer of '75. Jubilant, radiant, uplifting, the song's an irresistible blend of McCartney Active Ingredients: optimism in a hook-laden singalong, semi-obscure lyrics that sound great, maybe even profound, as a cheerful, addictive melody eddies them to and fro, indelible Linda-and-Laine backing vocals during an ecstatic chorus that feel like nothing less than stop-time footage of blooming flowers. McCartney and his band, rounded out with guitarist Jimmy McCulloch and drummer Joe English, produced a recording that is eternally warm to the touch, both song and weather. Prediction: a long, sunny afternoon.

I've been thinking lately about a metaphor in Robert Vivian's "Thoughts on the Meditative Essay," published in 2012. The "primary focus" of a personal essay, Vivian writes, "is not the self,"

though it uses the self and all that it has to give as a kind of booster rocket that, once the prose reaches certain insights, is jettisoned or spent, much like shuttles that are launched into outer space as we see those burning hoops fall back into the pearly clouds after they have done their proper work of achieving escape velocity.

A great image. I'm not a music journalist. I'm an essay writer who writes mostly about music, and my way into music is nearly always autobiographical. Hundreds of years ago Samuel Butler said that "every man's work is always a portrait of himself," and, yeah, that colors my writing about music. When I explore a song, an album, or a show, I usually keep my first-person POV front and center, threading the music through the fabric of my own experiences, and vice versa—however trivial or dramatic, mundane or confessional—either in the moments I'm listening or, more often, through the tangle of my past. Yet nearly every autobiographical writer must at some point answer the eternal question posed by the appealingly skeptical Joanna Polley, below, in her sister Sarah's probing documentary Stories We Tell. In her film, Sarah Polley investigates, among other things, mysteries and absences involving her mother's love life and the profound affects it might have had on Sarah herself.

Good question, Joanna. Otherwise asked: can you get past yourself, already? Every piece of writing begins in the dark inside a writer; hopefully they can bring something out into the light that moves them beyond the merely personal. I don't expect that a reader, friend or stranger, will take an interest in my life, yet I hope that they might care to stick around to see where a song might take me. I feel, perhaps too deeply, that being profoundly moved by a song is subject matter unto itself, and so I want to see how, when moved, I might move through a song as it soundtracks my days.

Hearing "Listen To What The Man" on Washington D.C.'s WPGC and later on my older siblings' copy of Venus and Mars (we had the 45, too) was nearly overwhelmingly pleasurable when I was a kid, less a daily sugar rush than a sonic shot of Vitamin D in an air-conditioned rec room in the middle of the suburbs. The song featured on a ceaselessly reviving inner-soundtrack to my solitary walks and bike rides, allowance strolls, basketball shoot-a-rounds, lounging at Wheaton Public Pool with the light diamonding off off the water surface. Family trips: rides on Funland amusement park at Rehoboth Beach against the dark Atlantic, hanging out in front of a Ben Franklin on a hot afternoon in rural Coldwater, Ohio. Saturdays with This Week In Baseball, my sister dancing in the basement... "Listen To What The Man Said" informed it all, in the air above my head. I couldn't wait to hear the song again the moment it ended, that poignant, half-time orchestral coda beyond my ken yet no less intriguing for that.

I'm guessing that the lyrics had something to do with all of this, too, though for me at age nine the words were no different in weight than the rhymes in the children's books I'd read only a few years before. "My stuff is never ‘a comment from within'," McCartney said about the song in 1988 in his fan club magazine Club Sandwich.

Basically I’m saying: ‘Listen to the basic rules, don’t goof off too much.’ But if you say ‘The Man’, it can mean God, it can mean ‘Women, listen to your man’, it can mean so many things. Later I did a song with Michael Jackson called ‘The Man’ and again, it’s quite nice leaving things ambiguous: I’m sure for Michael, probably ‘The Man’ meant God.

More recently, in 2016, asked again about the song's lyrics, McCartney said,

There are many answers to ‘Who is the man?’ In one way, you could say the man would be as the expression—‘You’re the man!’ Another way to look at it is that every religion has a leader who they consider to be ‘the man’. And his teachings are generally very positive. I like the idea that I leave it to the people to decide who, in their minds, is the man…".

Such optimism surely cut through the song as I listened as a kid, made me feel as warmly embraced as the melodies and McCartney's honeyed vocal, the very sound of hopefulness. That I can't divorce the song from the era, from my childhood, is immaterial to me as I listen now, so firmly embedded in my bone marrow is the song's tablature. Yet (I guess) I must steel myself against the siren song of nostalgia, that sop that dresses up as insight and passes as an argument.

There are a handful of songs that I listened to obsessively during the early months of the pandemic lockdown that I can barely listen to now because the rush of feeling, associations, and graphic memories overwhelms me. They are hot to the touch. The poet Adrienne Rich once described her early use of formalism as a "strategy—like asbestos gloves, it allowed me to handle materials I couldn't pick up bare-handed." I haven't yet located a pair of gloves resistant enough to the emotional turmoil those songs revive in me, and I can't approach writing about them yet lest I tumble into pure, wordless sensation.

McCartney, long derided by his critics for treading in shallow waters, has a knack for arousing surprisingly deep emotional responses to his listeners. Dig the joyful bridge in "Waterspout," cut in 1977 during Wings' London Town sessions but unreleased—"Only love can get you at it / and in a minute you will find yourself swimmin' in it." Gooey stuff, and also a heady evocation of lucky-in-love that's hard to surpass and might even put a smile on a McCartney hater's mug. He's plugged in, Sir Paul, and still manages to mine affecting currents.

Perhaps someone during the pandemic listened to "Slidin'," a gem from McCartney III written and recorded during the lockdown and released at the end of 2020, and was sent by the quasi-psychedelic chorus—

—someone who needed to feel a slide and glide out of the oppressive lockdown, for whatever reason. The song entered their DNA, and in a half century it might be impossible to listen to without the pulls and pangs of the mythic summer of 2020, but they don't care to sift the longing for objectivity, the nostalgia for critical thinking, they want to turn to the person next to them and talk about the wonder of it all.