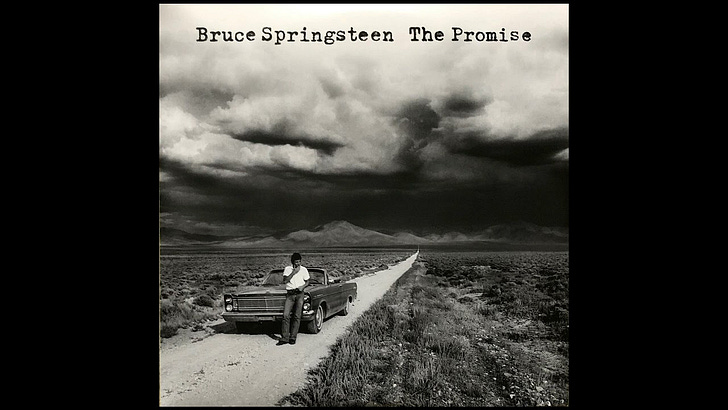

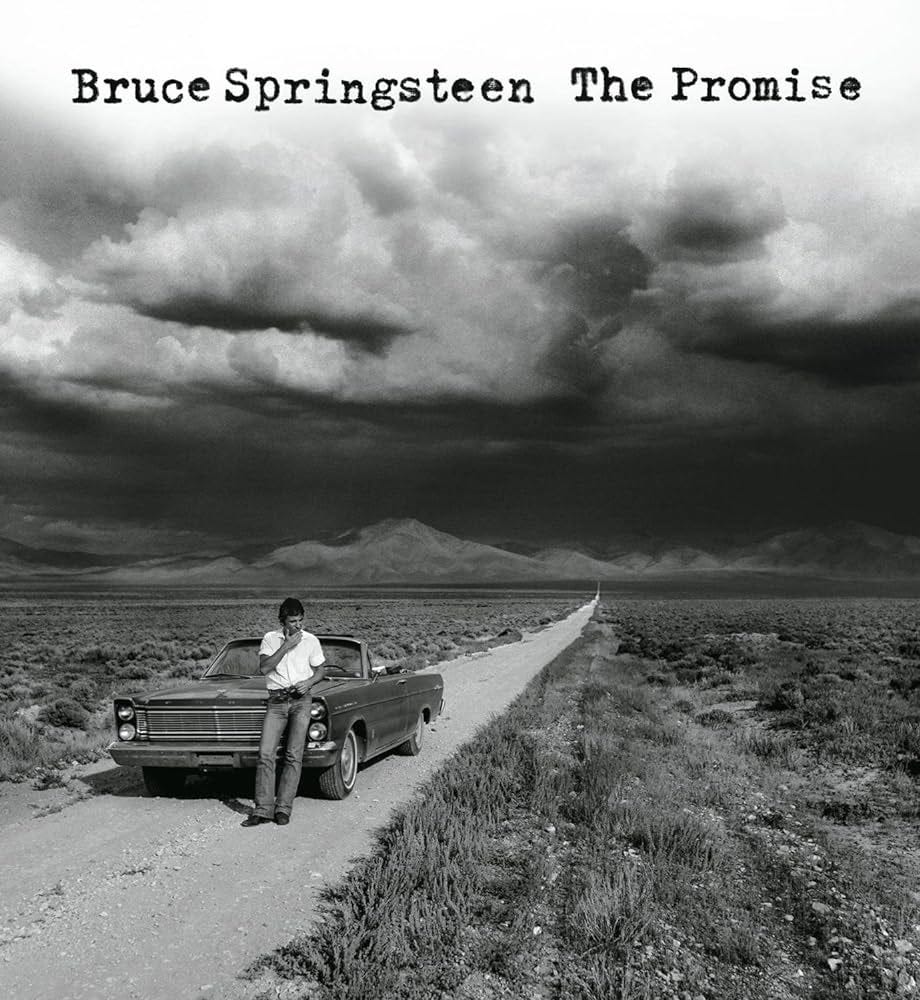

In 2010, Bruce Springsteen released The Promise, a “lost album” of tracks he’d begun with The E Street Band during the fraught, unhappy years between Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town. So astonishingly prolific was Springsteen during this period that he and his band recorded more than fifty songs, brooding, deeply emotional material that was eventually whittled down to the ten tracks that appeared in 1978 on the lean and mean Darkness.

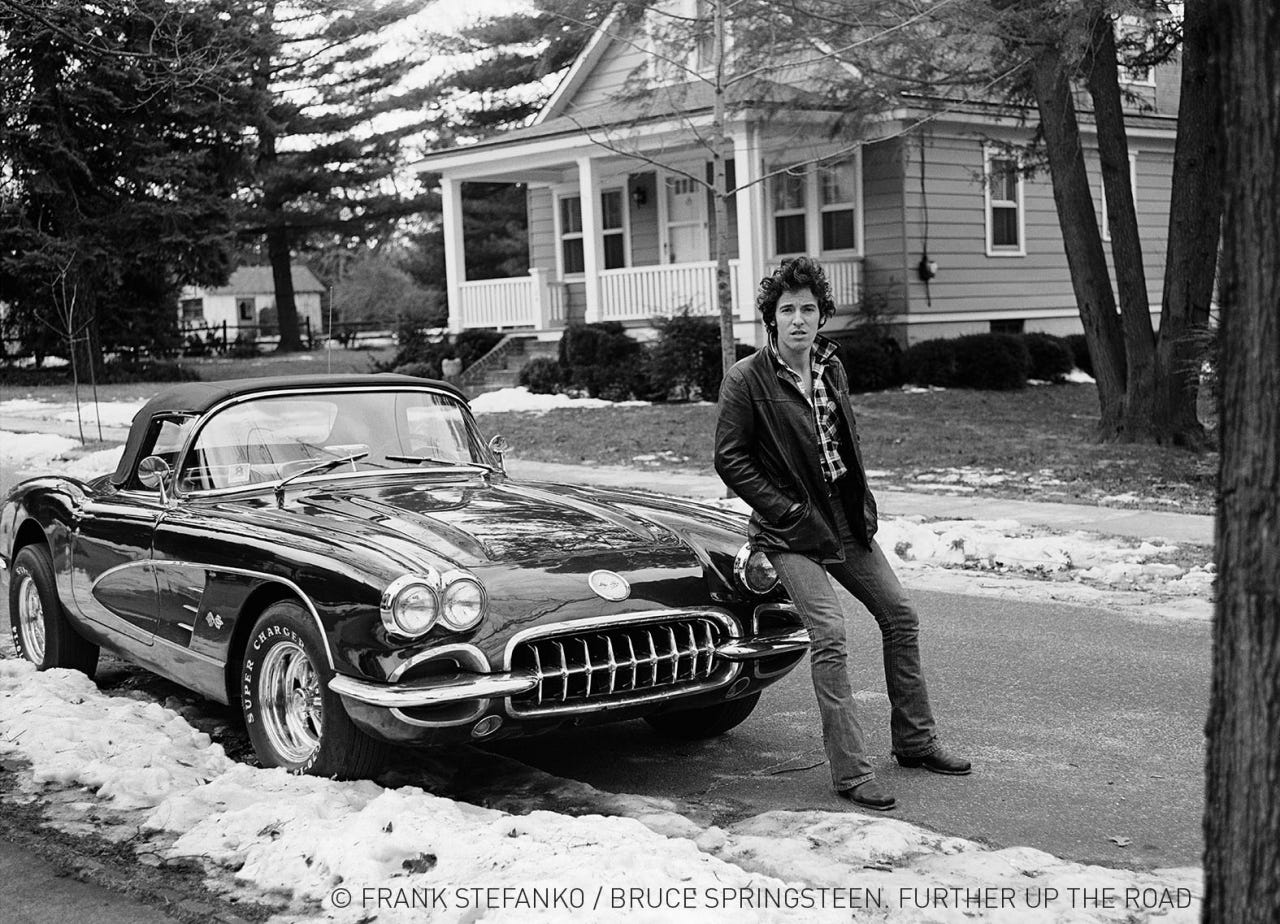

The era was a complicated one for Springsteen, as he moved between frustrating, legal-entangled inertia and his own native productivity. Blocked from releasing new material, he strained at the leash, imagining and reimagining the lives of the characters he wrote his songs about, and for, and what those songs should sound like. “By 1977, in true American fashion, I’d escaped the shackles of birth, personal history and, finally, place, but something wasn’t right,” Springsteen wrote of these years in his essential 2016 memoir Born to Run. “Rather than exhilaration, I felt unease.” Following the mammoth success of 1975’s Born to Run, he acknowledged the growing sense that “there was a great difference between unfettered personal license and real freedom. Many of the groups that had come before us, many of my heroes, had mistaken one for the other and it’d ended in poor form. I felt personal license was to freedom as masturbation was to sex. It’s not bad, but it’s not the real deal.”

Such were the circumstances that led the lovers I’d envisioned in “Born to Run,” so determined to head out and away, to turn their car around and head back to town. That’s where the deal was going down, amongst the brethren. I began to ask myself some new questions. I felt accountable to the people I’d grown up alongside of and I needed to address that feeling.

He added, “I was on new ground and searching for a tone somewhere between Born to Run’s spiritual hopefulness and seventies cynicism. That cynicism was what my characters were battling against. I wanted them to feel older, weathered, wiser but not beaten. The sense of daily struggle increased; hope became a lot harder to come by. That was the feeling I wanted to sustain. I steered away from escapism and placed my people in a community under siege.”

“Breakaway” was recorded on June 1, 1977 during the first night of the Darkness sessions, but left in the can until 2010, when Springsteen added a new lead vocal, backing vocals, and horns for The Promise. I am moved beyond reason by this song. Unfinished in ‘77—and the evidence is there: the new tracking, a line in the chorus later moving to its rightful place in “Badlands”—the song is dimensional now.

Sonny, Janie, and Bobby are familiar Springsteen characters, pared down here to their essentials. They’re desperate to break free—from their towns, their fate, their bodies—yet they're hemmed in by circumstance, shitty luck, bad choices, low ceilings. Springsteen recorded his vocal more than thirty years after making contact with these characters, and he sings as if the song’s still warm. Donny gambles away his life, Bobby goes down hard on the blacktop, Janie cashes out the bar she's working and the fucks a guy in his car, giving her soul away. (Springsteen doesn’t consider other, competing angles on Janie’s decision, that she might be empowered, or anyway looking for an aimless night of pleasure.)

The pace is measured, respectful of the vulnerabilities of the characters but mourning their lives, too. The melody is simple, to my ears among Springsteen’s most affecting. The verse melody moves simply and gracefully among three notes, until the melody descends toward the title phrase, the inevitability of that gently falling melody pulling each character down to their fate. In the chorus, Springsteen wills the melody to ascend again, against the brutality of the lyrics, but what he achieves is a kind of anti-lullaby, a woeful sing-song, or the musical equivalent of a feather borne atop a deceiving updraft, only to inevitably to drop and settle. Devastating stuff.

In his liner notes to The Promise, Springsteen wrote, “Post ‘Born to Run’ I was still held in thrall by the towering pop records that had shaped my youth and early musical education. Echoes of Elvis, Dylan, Roy Orbison, the full-voiced rockabilly ballad singers of the Fifties and Sixties along with my favorite soul artists and Phil Spector, thread throughout.”

As I page through my thirty-year-old “Darkness” notebook, I see a young man filled with ambition, a local culture/B-movie-fueled florid imagination, and thrilled to be a rock ’n’ roll songwriter. The nights of listening to Lieber and Stoller, Goffin and King, Barry and Greenwich, Mann and Weil, the geniuses of early rock ’n’ roll songwriting had seeped deep into my bones. Their craft inspired me to a respect and love for my profession that’s been the cornerstone of the writing work I’ve done for the E Street Band and my entire work life.

You can hear late-50s and early-60s song craft here ("ronde, ronde ray"). Certainly, Orbison is deep inside "Breakaway"'s DNA—from drummer Max Weinberg’s stately fills and the shadowy guitar shadings to Springsteen’s yearning melody and the ethereal background sha-la-la-la’s—but finally this is a dark, burdened song, and through and through it’s Bruce, amongst the brethren, at his most powerful, large-hearted, and sad.

As I've written about before, I love overhearing conversations that songs engage in over time. Springsteen has mined his characters' names and backstories endlessly over his career, a Faulknerian Jersey Shore universe-building. “Janey” and “Bobby” aren’t limited to the stories told in “Breakaway.” A “Janey” appears in both “Incident on 57th Street” and “Spirit in the Night,” a “Bobby” in both “Glory Days” and “Murder Inc.”

And both names appear in “Spare Parts” from 1987’s Tunnel of Love. (“Janie” is spelled “Janey” here, but the silhouettes are the same.) I imagine the “Breakaway” couple meeting sometime later, trying to make it work, but, alas, the cycle continues:

Bobby said he’d pull out, Bobby stayed in

Janey had a baby, wasn’t any sin

They were set to marry on a summer day

Bobby got scared and he ran awayJane moved in with her ma out on Shawnee Lake

She sighed, "Ma sometimes my whole life feels like one big mistake"

She settled in in a back room, time passed on

Later that winter a son came alongSpare parts and broken hearts

Keep the world turnin’ around

At the end of the song, Janey sells her wedding ring and wedding dress, a righteous fuck you to Bobby, and to that old life, reclaiming some measure of her soul that she lost in that car in the parking lot so many years ago. Let the hearts that have been broken stand as the price you pay, to breakaway.