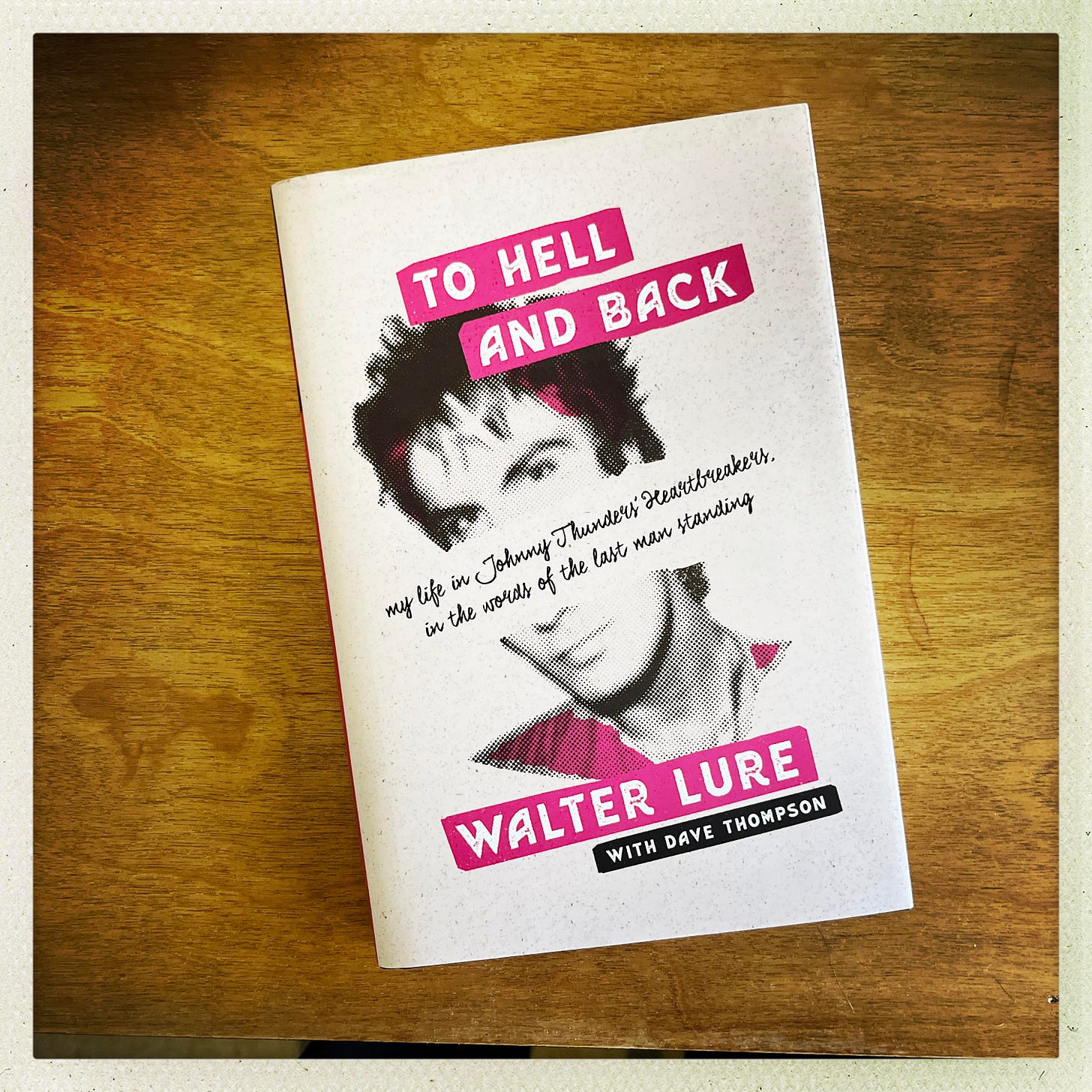

To Hell and Back: My Life in Johnny Thunders's Heartbreakers, in the Words of the Last Man Standing, written by Walter Lure with Dave Thompson, is an ideal rock and roll memoir. Reading it gives the impressions of having stumbled upon Lure in a talky, generous, above all clear-eyed mood, eager to share and to tell the truth. What Lure may lack in intense self-interrogation he more than makes up for in forthrightness. His book is very much a junkie memoir: foregrounded ultimately is the quest to score. A quarter of the way into the book—which primarily covers the first two years of the Heartbreakers' existence—Lure's already an addict, and when he's off the stage, his main preoccupation is getting more drugs, through the generosity of friends and strangers, via dwindling advances from record labels, or the cash drummed up by the various and many "rent parties" that he and whatever lineup he's in throw.

The Fleshtones' co-founder and bass player Marek Pakulski, himself a survivor of heroin addiction, once put it to me this way: "Heroin...obviates the need for people, whereas alcohol allows you to be present in social situations. Heroin says: You don’t need that anymore. You and whatever your income is, the guy you buy your drugs from, and your house: this becomes your little triangle." What rescues To Hell and Back from the potentially narrative-deadening routine locked within that triangle is the happy fact that in the late 1980s Lure cleaned up for good, and while in the clutches of heroin kept a regular diary. Hence, in writing about the fog of smack addiction, dateless days, and preoccupations, he can lean on some structure.

There are evocative details about visiting London and recoiling from the culture shock, the dynamism of playing onstage, well and poorly, both the conflicts and the camaraderie with like-spirited U.K. punk bands, good sex, anonymous sex, and fraught relationships, and the infamous recording and mixing epic of the Heartbreakers' sole album, the fantastic L.A.M.F.. In Lure's telling, Johnny Thunders, who Lure had known off and on before joining his band, fully lives up to his myth/image as the gloriously decadent junkie surrounded at all hours by disciples and hangers-on happy to hook him up, hopeful that some of Thunders's "glamour" might rub off them. Thunders is To Hell and Back's mercurial figure—as infamous when he's not around as when he is—frustratingly circling above Lure's more comparatively down-to-earth desires to get, and to keep, working.

Even given the relative assurances of diary entires, what's especially appealing about Lure is the dry skepticism he directs at his own past as that past as been remade my myth-makers. The venerable CBGB, long accepted as the hallowed ground of NYC punk, was just that, Lure acknowledges, but also something else. "'Punk' history tends to regard CBGB with a lot more affection than it perhaps deserves," he writes, adding, "Hilly Kristal himself merits every kind word that has ever been said about him—without him, and his vision, New York would never have seen the musical explosion that followed."

That’s true, but for me, mention of CBGB conjured another memory entirely, of the Sunday afternoon a couple of years earlier when a college friend of mine invited me down to a dive bar in the East Village to watch his country band play a show. I went, and it was a dreadful place, the kind you never wanted to think about again‚ which, at the time, seemed very likely because country was CBGB's specialty. But it wasn't mine.

Of course, it didn't turn out that way, and returning there for the first time only revealed that CBGB had only gone downhill since my last visit. It was a shithole, and just as you don’t think kindly of your cat’s litter box, no matter how much you love your cat, that damp, narrow room with its barbed-wire acoustics and broken-glass ambiance was a place you visited under sufferance not for fun.

A rock and roll lifer fan, Lure has attended (and remembers!) many shows in his lifetime, including seminal early gigs such as Humble Pie's 1971 Fillmore show and Woodstock (where, improbably, he ran into Thunders) and his love of 1950s and 1960s AM radio rock and roll is as palpable in the Heartbreakers' songs as it is in Lure's fond, if tempered, recollections of singers and bands.

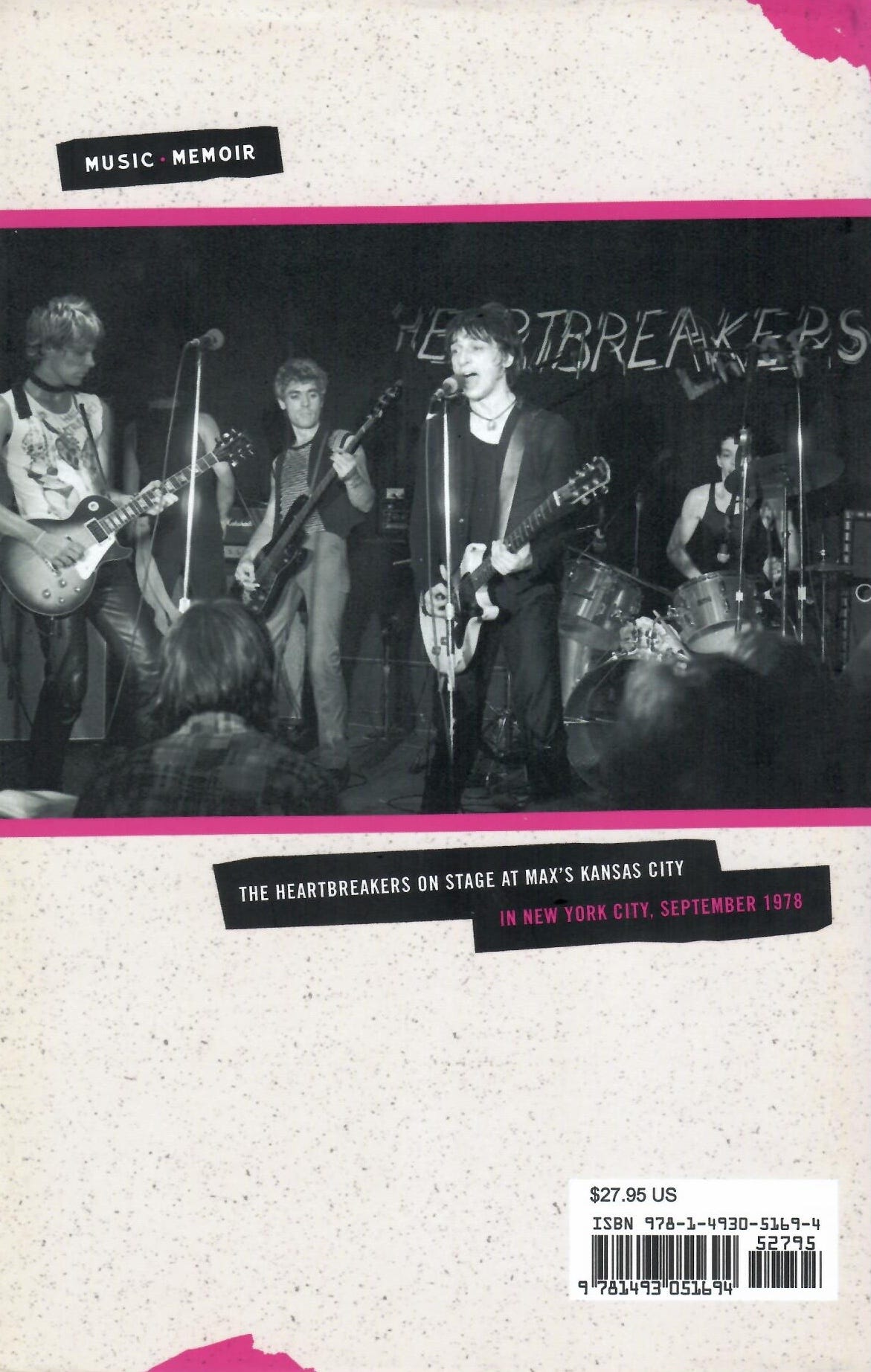

About his own band's legend, Lure acknowledges that their reputation as a great live outfit was (mostly) accurate, yet he's bemused at the way history can be re-written and accepted as gospel. Shaking his head in front of his open diaries, Lure writes, "To be honest, and I'm going to have to confess to this on a few occasions later, as well, the various history books and lists of our gigs include a lot that I have no memory of whatsoever and didn't note in my diary, either. Meaning, either I’ve always been forgetful or, and this is equally plausible, they’re shows that perhaps were scheduled and announced but didn’t ultimately take place for some reason." He adds with a smile, "I must admit, though, I especially enjoy reading about the shows we are supposed to have played around England when I know for a fact that we were elsewhere on that date." This leavening of hyperbole with dry fact serves Lure's memoir well, and underscores the simple fact that the story he tells is less about the making of legends than it is about men working hard, or trying to, dealing with the pitfalls of the recording and touring industries and their own bank-depleting addictions while trying to remain passionate about making music.

By necessity and through luck, Lure ultimately discovered other ways to survive. He was an employee of the Federal Drug Administration during the Heatbreakers' early days—that he doesn't have to make too much of the irony for it to resonate indicates just how absurdly thick that irony is—and in the last, harrowing days of his addiction, and for decades beyond, he worked on Wall Street, an equally improbable job for a smack-addict who wore bandaids on his face and played rock and roll in dim, sweaty clubs. Yet this work ethic, exploited early on to maintain his addictions, kept him alive. At the end of the book, he writes soberingly (in more ways than one), "if [the Heartbreakers] had gotten any bigger back then, we all might have died a lot earlier, given our proclivities at the time, and I include myself in that. One of the main reasons I survived was the fact that I had to go out and get a job. Johnny, Billy [Rath], and Jerry [Nolan] never had to do that—Johnny never worked a day in his life at a regular job."

Lure's happy fate is his book's happy ending. Near the end, he makes a simple but startling observation that casts so much of what he'd experienced, and written, in sharp relief: "Boredom was a relatively new sensation for me, and it was ugly. Powerful, too, in a sinister way."

It drives people to the most extreme lengths in an attempt to avoid it. I know “boredom” was very much a part of the punk ethic, and it was incredibly hip to claim you were bored—but actually being bored, as opposed to affecting weariness with the world, is a very different emotion.

A striking insight, simply stated, and one that goes to the heart of To Hell and Back: Lure survived Punk in part because he was able to make the crucial distinctions between myth and reality, between posturing theatrically and living authentically. That so many of his contemporaries, battling image and truth and drugs, couldn't, or wouldn't, see that clearly, is a testament to Lure. And now, standing, he gets to look back.