What do you do when the world's wrong?

The Rationals, SRC, the Free, the Third Power, and the earnestness of a lost era

In July of 2002 I was day-drinking at the Greenpoint Tavern in Brooklyn. The previous week my buddy Steve and I had hit the Siren Music Festival out at Coney Island—a long, fun day drinking at Ruby’s with the Fleshtones’ drummer Bill Milhizer, soaking up the sun and breezes, and catching a hell of a lineup including the Donnas, the Mooney Suzuki, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs. At dusk. Steve and I, drunk and sunburned, took the Q train back to Bedford Avenue, the subway barely crawling in the godawful heat. Everyone around us in that packed car looked like members or ex-members of the Strokes. Gazing back nearly a quarter century later, it was surely an Of The Era day.

At the Tavern, I’d struck up a conversation with a younger guy to my left. He’d been at Coney Island, too, and we traded stories about the bands we’d dug there. He was scornfully dismissive of the Mooney Suzuki. I’d seen the band a year earlier at CBGB where they’d raised the proverbial roof in an epic show, and I’d got off on their set at Siren Festival, too. Meh, said my new friend. “I hate all that corny stuff, all that ‘I climbed a mountain with my guitar, I came back down with this band!’ crap. So fucking corny.” Yeah, I laughed, and then trailed off. I didn’t feel like engaging, comparing credibility bonafides with this guy who was already several foamy 32-ounce Buds into his afternoon. Yeah, the Mooney Suzuki was kind of corny. And I loved it.

Lately I've been thinking about my ol' Brooklyn drinking buddy while listening to the Rationals, SRC, the Free, and the Third Power, Detroit-area bands that kicked out the jams in the late-1960s, early 1970s, the era that Mooney Suzuki and countless other bands have mined for sounds, style, and inspiration.

The Rationals toiled for nearly a decade, releasing snarling, strutting tracks including “Look What You’re Doing (To Me Baby),” “Respect,” and “Leaving Here,” and the blue-eyed soul of "I Need You.” By the time their self-titled debut arrived on Crewe, in 1970, the local and national scenes had shifted. The Rationals is in many respects a dated affair, from the late-psychedelic cover image of the fellas reclining on a trippy, orange-filtered hillside to the pastorally acoustic segues linking each song inside. Its strongest tracks—beautiful covers of the Knight Brothers’ “Temptation ‘Bout To Get Me” and Dr. John’s “Glowin’,” the boogie-funk on “Something’s Got A Hold On Me,” and the title track—indicate the power that the band legendarily possessed, in their tight, inventive arrangements, and lead singer Scott Morgan’s powerful vocals, which were part honeyed and soulful, part Fogerty and Seger. Alas, after The Rationals failed to sell, the band split.

“Guitar Army” is a rave up, a Midwest-bred anthem to the righteous power of rock and roll, the stuff in the DNA of fellow Michiganders the MC5 and the Frost (dig the Frost’s live exhortation “Rock and Roll Music”—it’s not Chuck’s). The phrase “guitar army” is so striking that John Sinclair used it as the title of his manifesto published a couple of years later. (Jimmy Page was enamored of the expression, too.) The song’s rallying cry, full-throated in the first verse—

Some folks talkin’ bout, burnin’ down

But I ain’t talkin’ bout, burnin’ down

Said I’m just talkin’ bout gettin’ down

—is dated on the page, yet in the excitable hands of Morgan (guitar, vocals), Steve Correll (lead guitar, vocals), Terry Trabandt (bass, vocals), and Bill Figg (drums) the song elevates from its earnest, end-of-the-decade beliefs in the transformative possibilities of music and in the expressive empowerment of fucking to remind you just what the fuss was all about, why the band felt inspired to get up and write the song in the first place. The Aww, yeah’s and Come on now’s surely were more stirring at the Grande Balroom than in the studio—Figg told David A. Carson in Carson’s essential book Grit, Noise, and Revolution: The Birth of Detroit Rock ‘N’ Roll, that if the band had had more say in the production, the album would’ve turned out different—but that’s often the case, as wild- and wet-eyed responses to live music mute a bit when musicians are tethered to mic cords under the watchful eye of the unforgiving studio clock. More than a half century after its release, “Guitar Army” still hums, not with the era’s naive assumptions but with that era’s timeless grooves.

Starting out as the Scott Richard Case, SRC released a clutch of terrific singles (including “I’m So Glad,” “Get the Picture,” “Black Sheep”) and in 1968 their eponymous debut; the following year they split from local promoter Jeep Holland (as had the Rationals). Though SRC was fortunate to be able to release two more full-length albums than what the Rationals could muster, they too could never bust out of the Midwest commercially. Two tracks on their marvelous, underrated second album Milestones (Capitol, 1969) evoke a gentler, sunnier take on the raucously eventful second half of the decade. “Show Me” is a blissed out, childlike invitation to openness and communion, the lyrics so simple and friendly—

Show me, if it makes you smile

We’ll see if it takes a while…

We’ve got the rest of the day

Show me and I’ll show you

—as to risk sweetening into dreck, and yet something—is it devotion? sincerity?—in Scott Richard’s vocals renders the whole, lilting thing genuinely, dimensionally heartfelt. Glenn Quackenbush’s organ solo evokes the fun of the fairgrounds, where childlike innocence has yet to curdle into skepticism.

Can a singer’s vocals be described as wide-eyed? That’s the vibe Richard gives on “Show Me” and on the trippier “Our Little Secret,” a two and a half minute slice of laid-back, sunny optimism, of belief in a future where the dark currencies of secrets and dishonesty lose their sinister value. Again, the song’s discoveries, offered in a supremely catchy, ear-candy chorus, are brutally simple—“Our little secret will be that we have no secrets at all”—and, yeah, the stuff of trite, come-on love songs. But here, as Steve Lyman and Gary Quackenbush’s guitars, Robin Dale’s bass, and E.G. Clawson’s drums provide a lush bed and Glenn Quackenbush’s keyboards extend a warm hand in fellowship, I’m struck but what feels eternal, what transcends the decaying ideals of the era. What a revolutionary and lovely thing to think, to sing about! The secret is that there is no secret. Dark and nasty incidents, on local and national stages, in bedrooms and the White House, swiftly arrived and are ongoing, of course, and so a the close of the day the cynical can fold their arms in smug victory. I’d rather let Richard’s charming, winsome vocals, and the sentiments they embody, lead me to places I distrust, and to see what happens there.

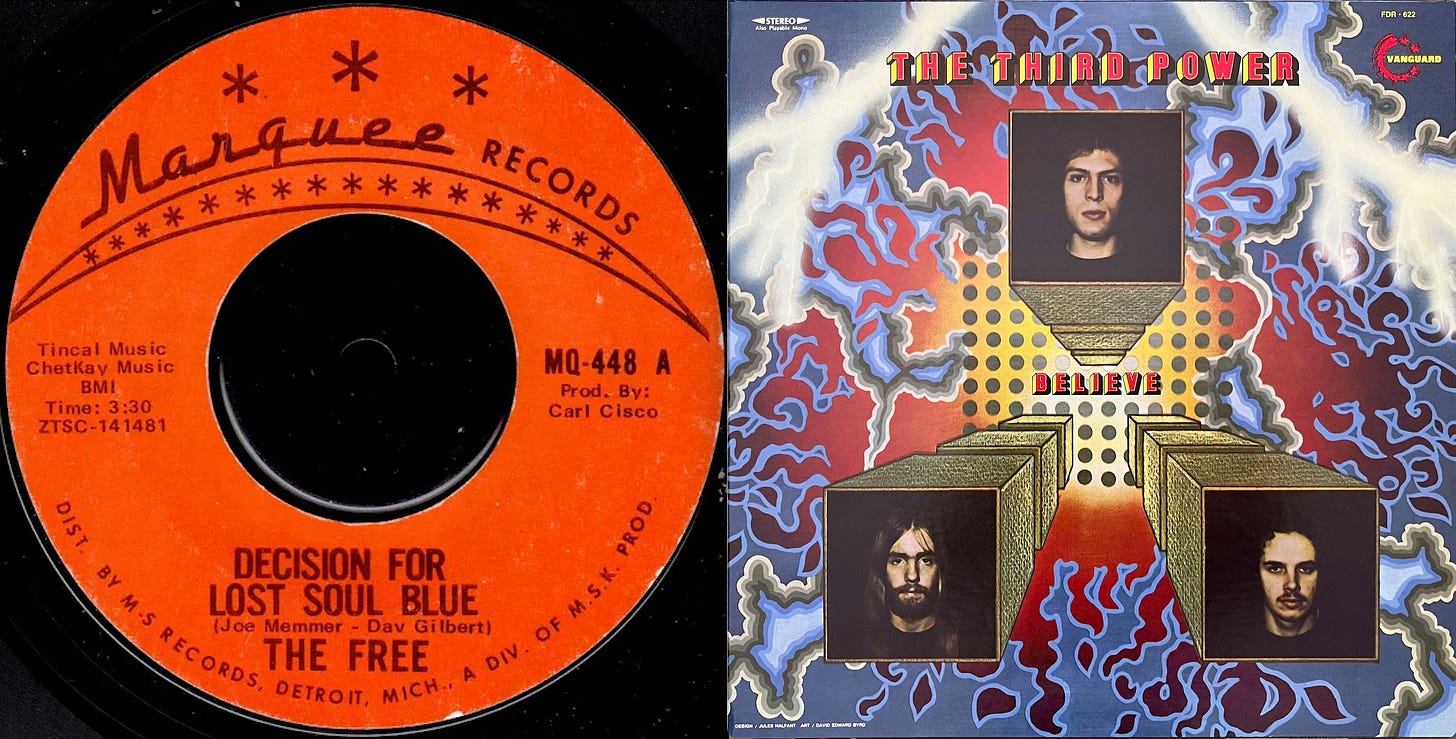

The Free's brief history has been unearthed by the usual intrepid sleuths; the folks at Garage Hangover and Kossoff1963 tell the story here and here, respectively. In short, the band was short-lived. Detroit-based, they included guitarist Joe Memmer and singer Dave Gilbert, who together wrote “Decision For Lost Soul Blue.” Area radio DJ Tom Shannon owned and operated Marquee Records with Nick Ameno and Carl Cisco, the latter of whom also managed Shannon and earned a production credit on the single, which was cut at Tera Shirma Studios. Released at the end of 1968, “Decision For Lost Soul Blue” enjoyed regional success, including a three-week stand as the “Pick of the Week” on CKLW. The major label Atco took interest in the local buzz, and in March of 1969 picked up the master recording to re-release the single.

Alas, despite the national distribution push from Atlantic, a Billboard mention, and a title change, the single vanished from the charts soon after, enduring the all-too-common fate of near-misses: a future of used record stores, thrift shops, online marketplaces, shuffling among hands of avid collectors, and appearances on obscure compilation albums (including Psychotic Moose And The Soul Searchers and Sklash—Rare Tracks From The Psychedelic Aera, both in 1982, and, more recently, Garage Daze: American Garage Rock from the 1960's in 2017). The Free split up within twelve months of releasing the single, their only record.

And what an amazing single the Free left behind. The tune’s a soundtrack to a resolution of sorts. It’s music to decide by. Who’s Blue? (And did they at an earlier junction mean Blues?) It was the era of lost souls, Summer of Love realists, early acid casualties. The opening ten seconds give the impression of things elevating, and it sounds as if we’re escaping something, tom drum to rhythm and wah-wah guitars, eighth notes propelling things upward. Then the singer arrives, and the litany of complaints, or heavy-lidded observations: the generation’s wrong, he’s sittin’ home wonderin’, people are turning their backs on each other, doctor can you help? The chorus is sung in a drone, and things are laid out starkly:

This is wrong, that is wrong

What do you do when the world’s wrong?

The second verse is less articulate—a shrugging anti-answer maybeeeeee is stretched out over three bars, answered by its anguished cousin don’t ever know a few long bars later—and doom’s still in the air. Everything feels a little more complicated, things churn. The chorus returns, and feels more dimensional now, but an answer to “What do you do?” feels further away than ever.

At the 1:40 mark a shriek tears at the fabric of the song, and nothing short of a different song begins. The rhythm section starts an aggressive, four-on-the-floor drone-march while for just over a minute the guitarists—one screeching in fuzz, the other answering in wah-wah, both languages foreign to the singer but native to the song—drag the song into a darker place. On some listens it gives the impression to me of a randomly plotted acid trip—many songs of the era attempted to sonically reproduce such a thing. Anyway, nothing’s solved. But it sounds great loud.

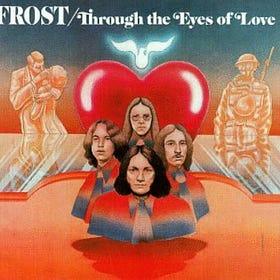

A classic power trio, the Third Power—bassist and lead vocalist Jem Targal, drummer Jim Craig, guitarist Drew Abbott—formed in the late 1960s in Farmington Hills, Michigan, a half hour drive from Detroit. Popular on the local circuit, the Third Power shared epochal stages with epochal bands and shacked up and partied fabulously in an era-defining communal farmhouse home. Their gigging, noise, and a locally-issued 45 landed them a contract with Vanguard, a somewhat odd marriage given the label's predominantly classical, jazz, folk, and blues artists. The band cut a full-length record, Believe, released in 1970 and distributed and promoted anemically. The album landed at number 194 on the Billboard charts, but swiftly disappeared, and the band called it quits shortly thereafter—a story so common and eternal it feels Biblical.

“Persecution” is very much a song of its times, little in the arrangement suggesting maverick, mold-breaking visionaries at work. Again, it’s basic anthemic blues-rock with “a social message,” hard to distinguish from other like tracks. As indulgent excesses and broken promises accumulated throughout the 1970s, such plugged-in glory began to look and sound trite, the heartfelt assurances that a song, in communion with a beatific crowd (and the right drugs), will unites us as One rang hollow. And yet with certain songs, certain bands, and at certain shows I feel the tug of those promises, however momentarily, however, yes, naively, my sober recognition of the promises’ limitations failing to decelerate the moments of bliss, thankfully.

“Persecution” begins with deceptive acoustic finger-picking before an electric guitar churns up a fat, funky groove. The singer—Abbot in this case; it’s his tune—complains about friends of his coming around and calling him names, lecturing him that he shouldn’t be playing “those silly games.” He shrugs them off before stepping down into the song’s chief complaint: “persecution, disillusion, yeah.” It’s hard to tell whether it’s a question or a simple stating of facts, and the laments pile up: his friends don’t like the way he plays guitar, doesn’t think he’ll get very far, but he couldn’t care less, and he’s gonna pick up his guitar and play. As rebellion goes, especially in 1970, especially coming out of rough-and-tumble Detroit, it’s pretty mild stuff, yet, as with the Scott Morgan and Scott Richard, Abbot’s sincerity is charmingly winning, and persuasive to my ears (and chest). He really believes that his guitar playing will raise a middle finger to mistreatment and blow off the shackles of disenchantment. His fiery guitar solos only raise the stakes.

"Decision For Lost Blue" was not a hit for the Free, didn’t unite millions of listeners and take its place in the open-air festival culture, wasn’t used numbingly often on soundtracks of films decades later “set in the Sixties.”

That was the Free’s bad luck. It’s my great luck. Because the song—along with “Guitar Army,” “Show Me, “Our Little Secret,” “Persecution,” and countless others—wasn’t embalmed, the song feels, is, fresh to my ears, and is in a very real and accurate sense undated. I've only recently discovered “Decision For Lost Blue.” I don’t have to blow off decades of sentiment about the 1960s while listening, didn't have to endure an actress in a flower power costume selling it to me on a Time-Life commercial, or watch as an eleventh-generation “Free Featuring One Original Member” hauls out the song on tour. (Though that might've been nice for Him.) I watch “Decision For Lost Blue” spinning on my turntable in real time, turn up the volume, close my eyes, and am timeless, out of time, with the song’s eternal question: what to do when the world is wrong? After SRC’s “Show Me” or the Third Power’s “Persecution” ends, life returns, and with it the scorn and cynicism that’s as at home in each of us as is generosity and open mindedness. It just depends on the day.

But I don't believe that a sincere gesture has an expiration date. I caught the Mooney Suzuki on a sweaty night in June 2001 at a packed CBGB where, song after song, they enacted for me these long-gone Midwest bands’ promises until I believed that they maybe were the answer. To what, I wasn’t so sure. I never fully connected with the Mooney Suzuki on their subsequent albums, on which their backward-looking, MC5/Grand Funk-inspired showmanship feels more contrived. The momentary stay under stage lights, the noise in a loud, dark venue, be it the Grande Ballroom, on the Bowery, in some small college town on a Wednesday night—that’s where such promises still feel like the opposite of corn.

See also:

Through the eye of a Beatle

This can't go on much longer

Dancing in the street?

Top photo: “Grande Ballroom Detroit” by Mike Boening Photography via Flickr

I'm with your drinking buddy on the Mooney Suzuki, but these are all stone jams!