What they wanted

The back sleeve of the Donkeys' obscure "What I Want" 45 tells an old story

The Donkeys hailed from Wakefield, West Yorkshire, in northern England. They never got around to releasing a full-length album in their brief career, their output confined to five bright and catchy singles issued between 1979 and 1981. (In 2000, the Japanese label 1977 Records reissued the batch, adding a previously unreleased single, “Shipwreck,” and four years later released the compilation Monkey Business. That same year, the Mod-focussed Detour label put out the two-disc Television Anarchy compilation, including twenty previously-unissued tracks.) The Donkeys were a terrific power pop outfit, loosely identified with the late-70s/early-80s Mod Revival scene, enough so that John Reed felt compelled to include their first single, “What I Want,” on his sprawling Millions Like Us (The Story Of The Mod Revival 1977-1989) compilation, released by Cherry Red in 2014.

I picked up that 45 recently. And what a debut it was. Brothers Neil (lead guitar, vocals) and Tony Ferguson (rhythm guitar, backing vocals) open “What I Want” with chiming, ringing riffs before Dave Owen (bass, backing vocals) and Mark Welham (drums) come charging in, Owen playing a counter melody on his bass. The song’s a simple plea, a statement of desires (I want you to stay forever; I want you to make me shiver; I want you to write me letters) married to a beat and powered by an anthemic chorus that make those wants palpable. The inventiveness comes in the unexpected chord changes at the end of the second line in the verses—each time, it sounds like a smile unfolding on the song’s surface—and in the bright harmonies. Cheery, glinting harmonies enliven the Donkeys’ best songs (“No Way,” “You Jane,” “Don’t Go,” “Let’s Float”) garlanding melodies that recall the glories of mid- and late-60s Top 100 AM radio. (To my ears, the Donkeys also suggest a U.K. take on suburban Chicago power pop champions Off Broadway, Pezband, and like bands.) Producer Andy MacPherson, recording at his legendary Revolution Recording Studios in Manchester, gave the Donkeys real kick, as it were, harnessing their dynamic and muscular energy, and balancing their sound nicely.

The Donkeys didn’t last long, but a handful of their songs endure.

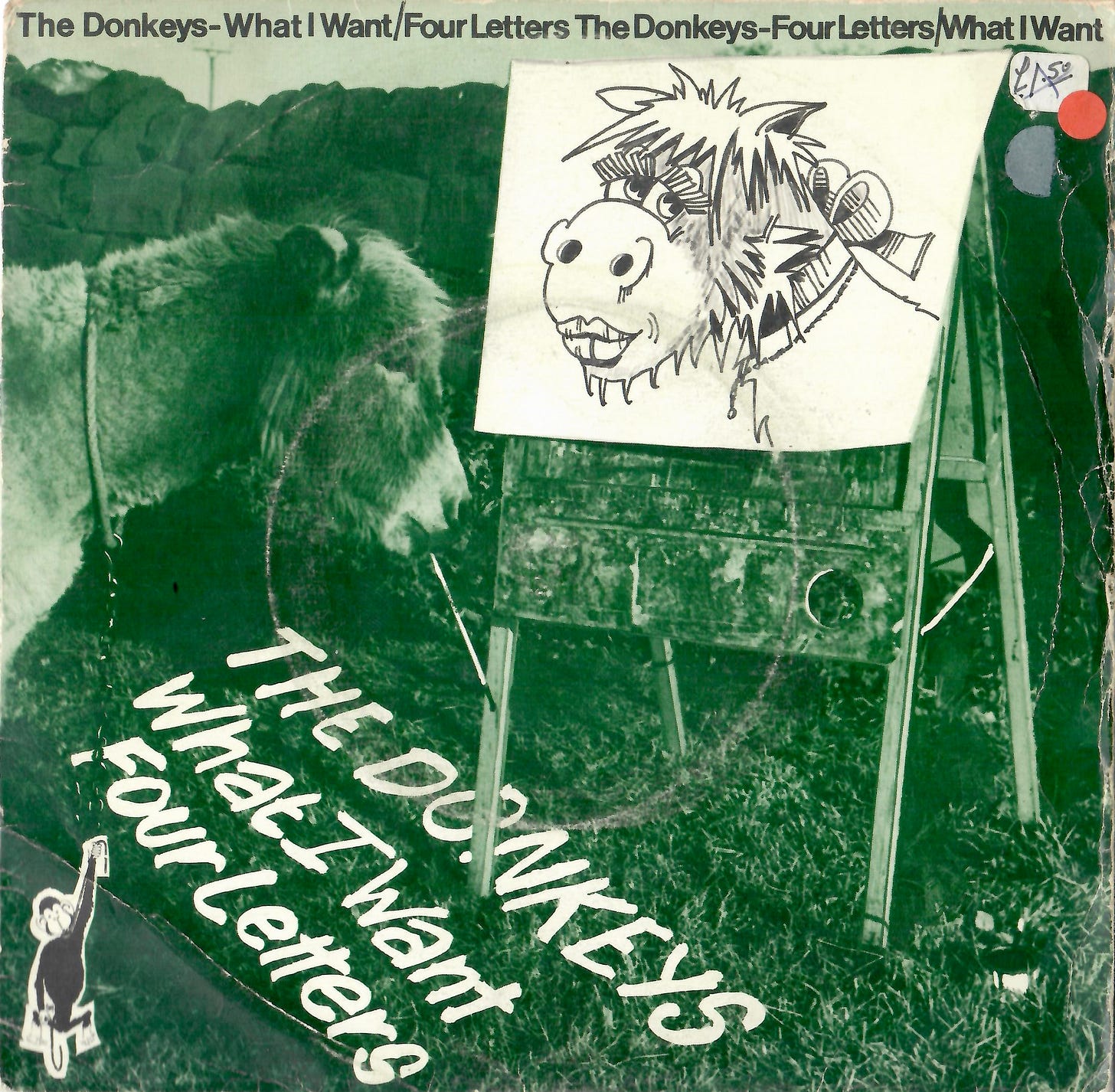

But for my purposes here, I’m more interested in the picture sleeve in which “What I Want” arrived. The front (above) depicts a donkey, brush in mouth, who’s facing an easel and painting another donkey. Is this a self-portrait? Possibly, yet the long, luscious eyelashes and bee-stung lips suggest that the subject’s a Jenny, the artist, well, a jackass. The concept sprang from the mind of Tony Ferguson, who was aiming for something funny, or an in-joke perhaps.

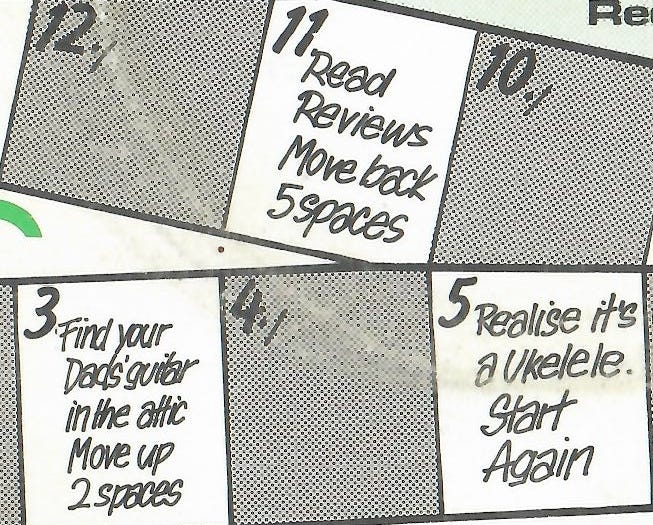

Anyway, it’s the back of the sleeve that wins the day: a mock board game, The Game of Life writ small as the trials and tribulations of a young and hungry rock and roll band. There are twenty-seven spaces on the board. Roll the die and leave your commercial fate to randomness and chance! If you start by rolling a three, you’ll discover “your Dad’s guitar in the attic.” Inspiration! An origin story! You’re then invited to “Move up 2 spaces” where you’ll land on the fifth space, only to “Realise it’s a Ukulele. Start Again.” The ninth space promises “First Gig” and a promising advance of two spaces, where you’ll then “Read Reviews” and “Move back five spaces.”

The idea of leaving a band’s future to the throw of a pair of dice is brilliant, and grimly hilarious, a career turned into a perverse kid’s game, which the slog of a straggling band might feel like at times. It took me several glances at the sleeve before I noticed the witty title: “A Bored Game.” (There was something in the air in 1979: “It’s done with the use of a dice and a board,” the Jam sang with withering clarity in their single “When You’re Young.”)

A close examination reveals more headaches and setbacks than thrills and victories. If you’re unlucky enough to land on the seventeenth space, you’ll “Play Working Men’s Club” and then “Miss 2 turns to recover.” Two spaces later, you’ll commit a far worse mistake: “Tune-up by accident. Move back 3 spaces.” Etcetera. There’s one bit I don’t fully understand, likely because my Yankee ears are tuned to a different frequency; on space twenty-five, you’ll “Get on Tony Blackburns Playlist.” That sounds like a good career move to me. Blackburn is a U.K. radio DJ who’s best known as one of the original presentees on BBC Radio 1, after having worked at the pirate stations Radio Caroline and Radio London. (The first song he played on the BBC was the Move’s “Flowers in the Rain.”) He moved to BBC Radio 2 in 1975, and at the time of the release of “What I Want” was a leading Radio 2 voice and presenter. So perhaps one of my English readers has a theory as to why making it on Blackburn’s playlist resulted in a penalty for the poor musicians: “Move back 3 spaces.”

In Milton Bradley’s Life, which has been around in one form or another for a century and a half now, players cruise around the board in cars, make life decisions, deal with surprising events. The goal of the game: finish with the most money. The Donkeys’ “Bored Game” offers that tantalizing prospect, as well, yet with a bitter, Naturalistic twist: if you’re fortunate enough to make it the final space, you attain “Fame and Fortune,” alright, but you must, in Sisyphusian agony, “Start Again.” You’re only as good as your last hit, I guess, and professional and personal scandals lurk at every corner. The Gods of Riches and Celebrity are fickle, indeed.

Perhaps if the Donkeys had had a “Fran the Fan” on their side, they might’ve withstood the vagaries of bad luck.

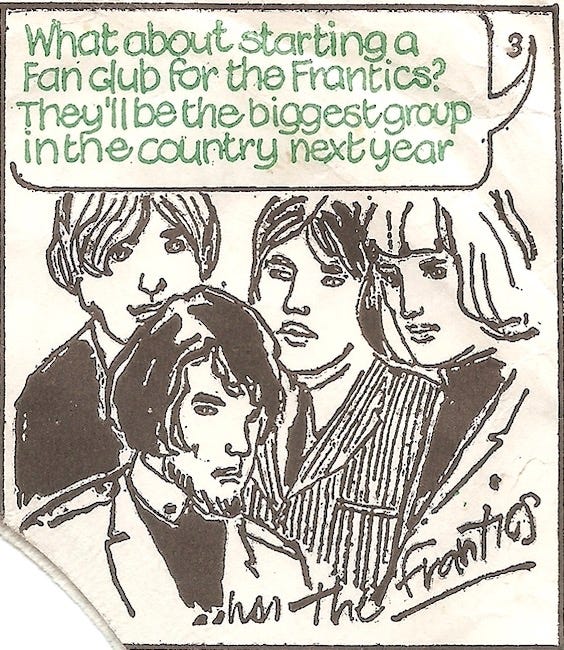

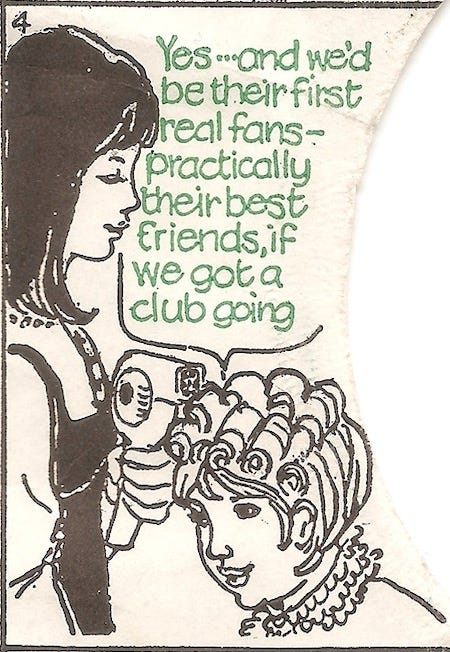

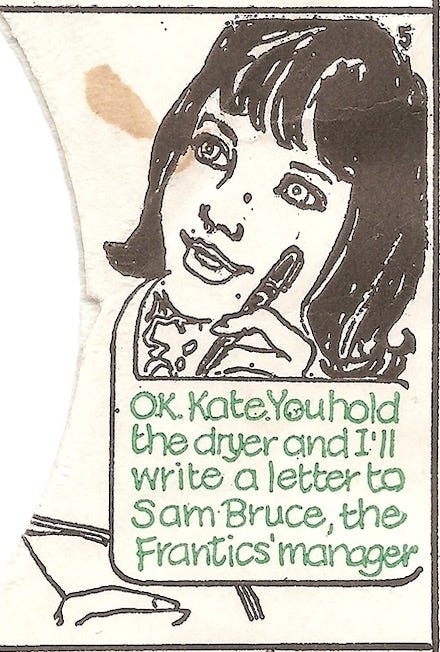

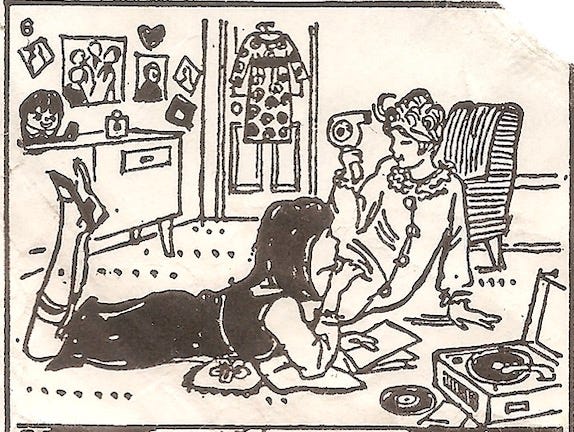

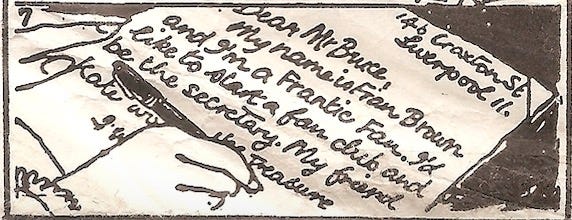

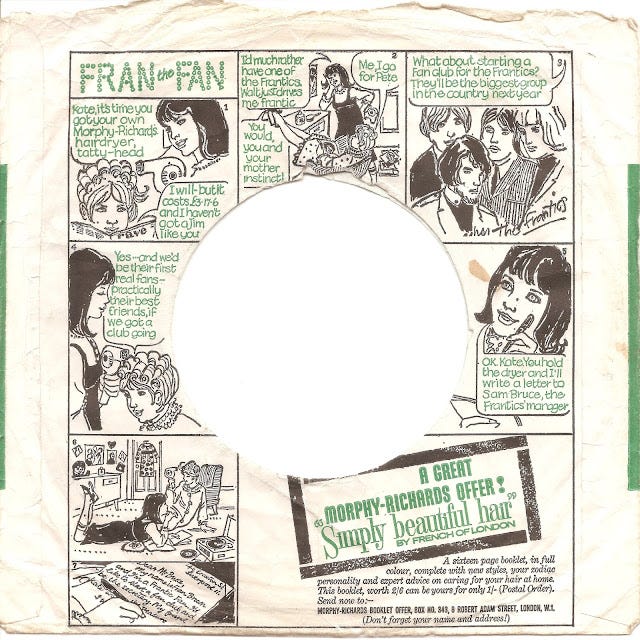

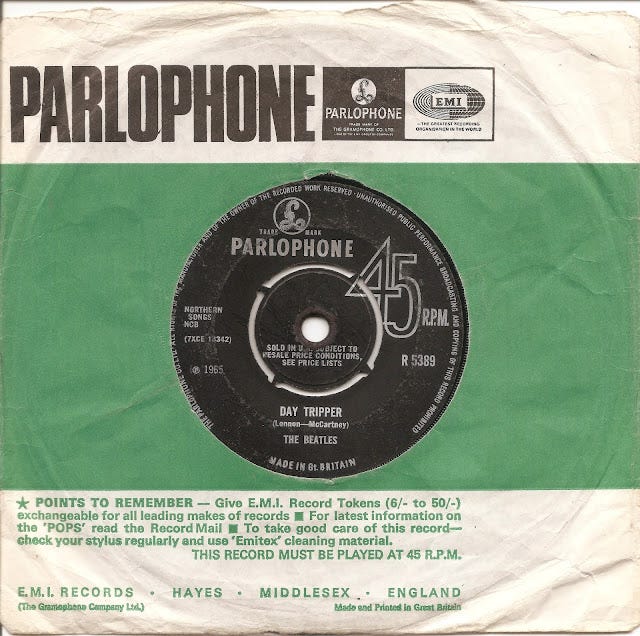

The ad below appeared on the back sleeve of the Beatles’ “Day Tripper”/”We Can Work It Out” single, issued by Parlophone in England on December 3, 1965, the same date Rubber Soul was released. I picked up the 45 several years ago in my ongoing quest of collecting the original Beatles U.K. singles (and wrote about it briefly at my old blog). I was knocked out to discover that this comic book narrative played out as an advertisement for a Morphy-Richards hairdryer. (Between July 1965 and late 1966, Parlophone featured several vignettes with “Fran the Fan” on the back of Beatles 45 sleeves, and presumably on other artists’ as well. More examples here and here.)

In this episode, Liverpool lasses “Fran” and “Kate” are inspired to start up a fan club for the Frantics, a fictional northern band destined to be “the biggest group in the country next year.” (We’ll see!) The girls are far more interested in the Frantics’ “Walt” and “Pete” than in their own boyfriends. Who’s the moody, arty one with the goatee? Anyway, the girls are amped to be the band’s first real fans—“practically their best friends!” Kate enthuses, helpfully holding the dryer as Fran composes a careful letter to “Sam Bruce, the Frantics’ manager.” All innocent fun and girlish enthusiasm, yet the girls’ wide-eyed hopes of securing relationships with a rock and roll band, as embedded in an advertisement for a hair dryer, evoke the comparatively sexist era in pretty graphic ways. There’s a tantalizing “special offer” at the bottom of the sleeve: a sixteen page booklet, “in full colour, complete with new styles, your zodiac personality and expert advice on caring for your hair at home.”

The power of the beauty-industrial complex, gender role playing, biological determinism in the bedroom as “Day Tripper“ spins on the hi-fi, that sly song’s teasing weekend-girls playing out another, dirtier story altogether. Ah, pop music.

You might also dig:

Listen, does this sound familiar?

Yesterday afternoon, I was moving slowly through the parking lot at Jewel. Stuck behind a car, I tuned into the local NPR classical music station. A cello and piano piece was playing, and within moments, the grimy, humdrum landscape changed. So much instantly felt charged with the possibility of story: that woman pushing her cart now a matriarch on the …

All the notes seem to ring in my ear

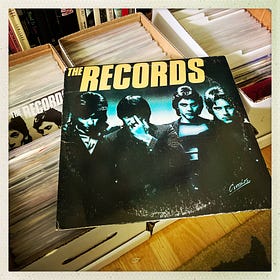

A burst of light can be so powerful that its after glare can momentarily obscure anything nearby. Such was the fate of the Records’ second album, Crashes, released in 1980. The band’s debut, 1979’s Shades in Bed, was a glorious blend of power pop, high harmonies, enduring melodies, durable hooks, and witty lyrics, typified in such killer tracks as “Star…

A long way from the valley

Back in 2010 I wrote a book about AC/DC’s Highway to Hell. The album had come out when I was an impressionable teen, and decades later I still loved the record. I wondered what that meant. Does my affection for the album and the band sit somewhere between earnestness and irony? (

Tony Blackburn was spinning MOR by the time The Donkeys began braying. No advocate of puNk, he famously trashed "Down In The Tube Station At Midnight" on Radio 1's new releases show one Friday evening. Blackburn believed the song encouraged violence. Weller was listening and was so incensed he rang the station to correct Blackburn. Hence, any young forward thinking band's reluctance to be associated with such a musically conservative DJ .

Another great meditation— and without the plodding feel of a Robert Christgau— on rock and pop.

I’ve got to finish reading the section on the Game of LIfe record sleeve, but here I’ll just say that the Donkey’s music and mod and power pop generally were doomed to be a niche taste once the 70s and ROCK took over. And, yes, AC-DC epitomizes that. Despite sex roles being in place, the Mod and power scenes audiences seemed less male dominated. The bands, the songs had a yearning quality. There was a lot of young male energy looking to smash its bottles but not the swagger most mainstream rock had.

Anyway, Joe, your music writing is a pleasure to read. And I still love the essay collection I bought direct from you a couple of years ago.

Are there any other pieces about small “s” spirituality coming(à la the prayer essay?).