Writing from Jubilation: Duncan Hannah's New York Stories

What's the literary value of a diary?

Beyond being a time machine into the past, a diary can describe a real tension between grown-up and youthful selves. Most adults are no longer tuned to the mania and energy of the their youth, but they are to the larger universal underpinnings of that youth, what all that sweaty, blind striving was about; a grown-up may have slowed a bit, but the big picture's clearer. Speeding along as we do in our twenties, we can't see it. A diary is a snapshot of a blur; later, wide screen wisdom takes a while to emerge, though it's less sexy.

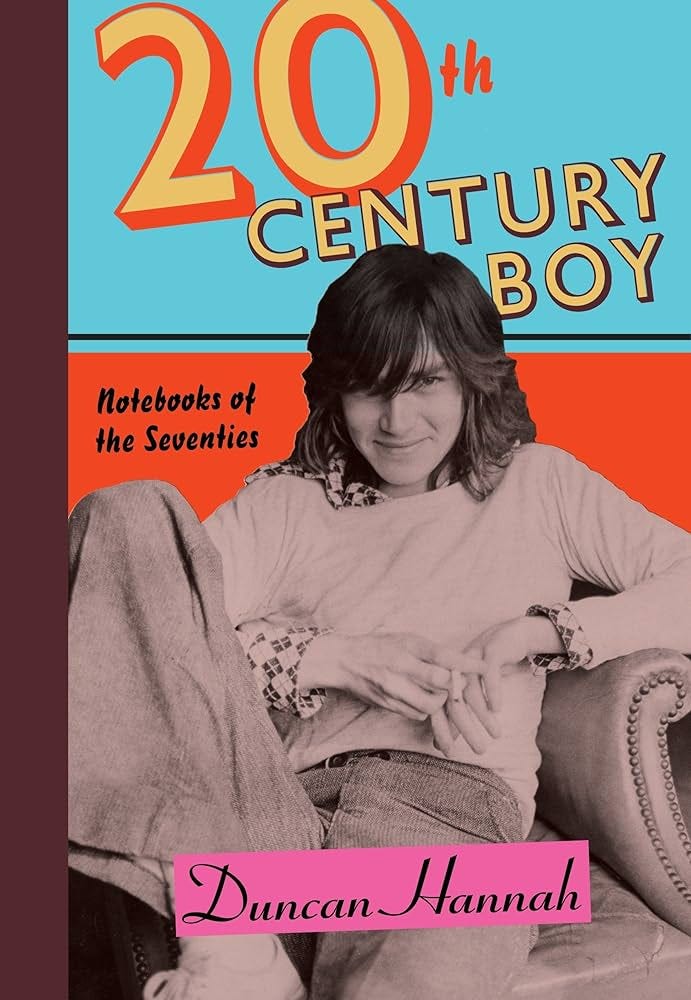

Painter Duncan Hannah's remarkable new book 20th Century Boy: Notebooks of the Seventies, chronicles what Gillian McCain drolly describes as "the adolescence that most of us wish we had." Born in 1952 and raised in Minnesota, Hannah attended art school, then transferred to Bard and then to Parson's, in downtown Manhattan, in the early 70s, just as the city was both declining into a social morass and ascending in shabby glamour. Hannah seems to have been blessed with amazing luck: he shows up at a concert, and ends up backstage partying with his rock gods; he drinks and drugs excessively, winding up in predictably dangerous and dire situations, once in an abandoned apartment hundred blocks north of where the party started with no recollection of how he got there, yet survives again and again; he creates defiantly unfashionable art (representative illustrations and painting in a heavily Abstract era) but meets the right people, and ends up making a living. His twenties was an extraordinary crash course in alcoholic depths and plucky providence, presided over by what Hannah calls his guardian angel. If you want a mad dash into Downtown NYC as Glam ruled and Punk was stirring, artists were thriving in low-rent lofts, and larger-than-life personalities seemed to pop up on every corner, party, and dark dive bar, you will inhale 20th Century Boy.

How many grains of salt you'll need for the ride is a personal call, I guess. I did some low-key fact-checking of Hannah's exploits, and most of the amazing events he witnessed and involved himself in, either as a drunken fly-on-the-wall or as the center of attention, did occur. Yes, Jagger was in London when Bowie played the Rainbow Theatre and so likely was there, dancing in the front row; the infamous issue of Rolling Stone with a half-naked David Cassidy on the cover did come out around the time a couple of English giggling school girls mistook Hannah for the Partridge. I can't account for the numerous run ins with scenesters and rock stars that Hannah, a relatively unknown artist in the city, describes, and neither can he. One of the problems with diaries, as with all autobiographical accounts, is legitimacy and authenticity. Hannah implies in his introduction that he didn't rewrite his diaries, but there's nonetheless an occasional feeling as I read of retroactive shuffling, of today's insights pushing against the immediacy of the diary's present tense—did Hannah really feel that stepping into CBGB for the first time felt like the dawning of a new era? "It's like watching the birth of a wildly frantic and perverse new subculture," he gushes in the entry. Perhaps. We often sense something, even an epoch, before our language catches up with us. Or did Hannah touch up that entry with a bit of hindsight? "I had never read these journals before transcribing them," he confesses in the introduction.

In preparing them for publication, I removed a lot of extraneous detritus. I didn't do a lot of navel gazing, as many diarists do, so I didn't have that to contend with. I noticed, at the time, that mostly it was girls who kept journals, and they generally wrote only when they were upset. I was determined not to do this. I tended to write from jubilation. I wrote these at night, in bed (if I was in any kind of shape to write), or in the morning, over coffee. I didn't write every day, and as life accelerated I would miss notating chunks of experience. Indeed, 1979 hardly gets a look in at all. I don’t know why. I’ve changed some of the names to protect the innocent, and also the not-so-innocent. The grammar and spelling have also been corrected, as my slipshod grasp of English composition leaves something to be desired.

The book's early diaries are marked by long, narrative passages, as if Hannah was conscious of the story he was living, and making; the later entries are far shorter, often impressionistic, less episodic. His addictions were growing by this point, and no doubt the blackouts were more frequent. How Hannah recalls as much as he did in a state of near-continual inebriation and forgetfulness is also somewhat dubious, but, again, the art is in the shaping.

Stars and starlight abounds. Hannahh meets Bowie and Janis Joplin, Iggy Pop and David Hockney, Warhol and Lou Reed and Richard Hell and David Johansen; Flo and Eddie ask him if he's got weed; he starts an early Television fan 'zine, and Danny Fields becomes his tour guide into and out of the Downtown jungle of artists and scene makers. He hits Max's, CBGBs, and later Hurrah and Mudd Club. He somehow gets invited to most of the best parties, where he's usually chased around by older gay men. Hannah recognizes his appeal to queers—it's been a lifelong dynamic. But he's straight, and he gets laid, a lot, even judging by the bed-hopping standards established in other memoirs of the era. Hannah was young and beautiful with a beatific, boyish innocence that was catnip to women, most of whom in the book are curious, independent, and generous, yet mask some serious psychological unease. It's a drag to admit that the sex gets a bit dull to read about after a while. By a third of the way in, each time a woman enters a scene it's virtually guaranteed that somehow, somewhere—in a borrowed bedroom, in a car, in an attic, in a shabby room in the Village or an estate on Long Island—Hannah will be alone with her, clothes will fall to the floor, hard nipples will be admired, and welcoming vaginas will be poetically praised. The readiness of so many eager women borders on the pornographic. It was the era. Yet it's always a shame when good fucking becomes predictable or dull in the retelling.

Hannah and Jim Carrol shared an editor, and Carrol's Beat Punk jittery ghost floats in and out of the book, in the staccato prose and epiphanic wooziness, such as in this entry from February 1976:

It’s already springtime, tweet tweet. Nick [Hannah's cat] got his balls cut off at the vet on Tenth Street. I waited for him at the Lion's Head. (He’ll take a fishtail, turn it into a fish scale.) Meaney’s got a friend of a friend who got castrated by some S&M guys last week. Eric got mugged when he was high on downers. Guillemette Barbet got her cameras stolen. E. S. Wilentz’s Eighth Street Bookshop burned down. There’s a full moon all this week that’s got all the ghosts and skeletons jittery. It gets crazy around here, and none of us have stuntmen to fill in for us.

Carrol and Hannah also shared a love of music, and pulsing throughout 20th Century Boy is the sound and spectacle of rock and roll, Hannah's second great passion after art. His description of Iggy Pop's drunken collapse at the Academy of Music on New Years Eve 1973 and of Bowie's New York City debut at Carnegie Hall are epic; throughout, his memories of shows and gigs are shot through with the sheer joy of fandom. Hawkwind bores him, but the New York Dolls, Roxy Music, and Mott the Hoople thrill him. Describing listening to the Velvet Underground's Loaded and the Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle in a September 1970 entry, he marvels, "...fantastic. Such a rich wealth of music coming out. It’s where we get our messages, our subversive directions. It’s the soundtrack to our lives. The centerpiece to all this action. Ties us all together."

The Rolling Stones pop up often in the book, and it's quite interesting to see just how pervasive an influence the band was into into the mid-70s, even as they approached their alleged Dinosaur Era. Hannah continually seeks a Keef Richards haircut, and pre-sex with a girl once, he takes Joni Mitchell off of the turntable and slips on the Stones, "to get the right groove going." "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" was as intense to him as a teenager as the Stooges' Fun House was when he was a bit older, and nothing was lost in the trade-off. In yet another instance of Hannah being in the right place at the right time, he inadvertently witnessed one of the Stones' great PR moves in May of 1975. I'd always wanted to read an on-the-ground description of the time the Stones roared into Manhattan on a flatbed truck singing "Brown Sugar." They'd actually simply turned a corner onto Fifth Avenue, but the spectacle was eye-popping. "Yesterday Mary Jane and I were walking north on Fifth Avenue to school," he writes. "I heard what sounded like a garage band playing 'Brown Sugar.' Loud! Outside! At ten-thirty in the morning? On a weekday? What is this?"

There was a small crowd in front of the Fifth Avenue Hotel on Tenth Street. We were on the east side of the street, looking at the back of a large flatbed truck. That’s where the live music was coming from. From under the partition I could see rolled-up Levi’s and Frye boots. I ran around to the front, maybe four people deep from the lip of the stage. It was the Stones themselves! They threw a press breakfast party for all the NYC journos inside Feathers restaurant, whose windows face Fifth. The scribes were reportedly pissed off that the Stones hadn't shown up at their own press party to promote their extensive summer tour, only to have them roll right up in front of them and begin to play. I caught the end of their first number, then they raced into the next. They looked appropriately scruffy in denim and worn leather, good shag haircuts, Mick's lips, etc, Their backdrop was a giant eagle with jet engines (drawn by one of my favorite illustrators, the German Christian Piper). Then the skies broke, and the rain came down in earnest. Police cars began to arrive. The truck began to drive slowly off, a gaggle of kids racing behind it. I finally saw the Stones!

20th Century Boy is a wild, mostly thrilling and engrossing chronicle of a thoughtful, talented, and fortunate boy's journey through one of modern Manhattan's most storied eras. If you dig the 1970s and its art and music, you'll love Hannah's in-the-moment accounts. The New York Times found Hannah recently and wrote about him here and here. Please Kill Me featured him in an article here.

For what it's worth, my favorite detail in the book is David Bowie drinking Schaefer Beer at an after hours party in Larry Rivers's loft on East Fourteenth Street following a Roxy Music show in 1974. He probably had more than one.