You don't know what it's like

Dee Dee Ramone's best songs mount a storyboard of triumph and tragedy

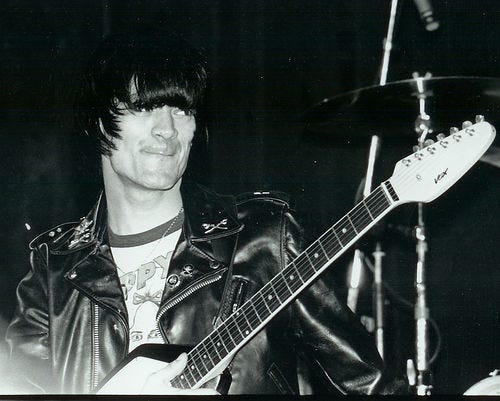

I took a long drive the other day with the Ramones on shuffle. If I could, I'd write a screenplay or novel based on the songs that Dee Dee wrote or co-wrote for the band. There's a great character-study story there of urban disaffection, addiction, triumph, and tragedy. I'm currently re-reading Poison Heart: Surviving the Ramones (written with Veronica Kofman), struck again by Douglas Colvin's fucked-up adolescence as the wayward son of a brutal alcoholic father and generally indifferent mother.

His book's semi-fictional, grouchy, and riven with paranoia, pockmarked with errors, misremembering, and petty grievances, and swerves from topic to topic—so, in many ways it's an ideal rock and roll memoir, energized by a storied man at the end of the bar chatting off the cuff, moving between honesty and mythology. Ramones' lighting and art director Arturo Vega's quoted in Monte Melnick and Frank Meyer's On the Road with The Ramones as saying that "Nothing of what [Dee Dee] wrote [in Poison Heart] is 100 percent true. In his mind it became indistinguishable to write something that was supposed to be autobiographical and to write a song or to write a chapter in a book—there was no difference. All the differences were erased."

It wasn’t intentional. He wasn’t doing it to be more provocative or to shock; it was more an artistic decision. He wanted to live his life like his art. His life and his art became one. It’s not that he was lying, but he was creating at the same time he was supposed to be writing the truth. His intention was to create exciting literature.

In his autobiography Punk Rock Blitzkrieg, drummer Marky Ramone concurs, remarking that Dee Dee "fantasized the way other people breathed," adding, "It didn't make him a reliable witness, but it made him a great songwriter."

Shuttled among military bases until settling in Forest Hills, Queens, Colvin found refuge in drugs, rock and roll, and male friendships, eventually learning bass, forming the Ramones, and changing his name, not necessarily in that order. His history of drug abuse and mental strife is melancholy, to say the least, and the pole between normalcy and instability was a wide and difficult gap for him to bridge. A famous person, he's an Everyman addict. His story's painfully familiar. I've always been attracted to the characters in his songs, who seemed genuinely and graphically punk to me, despite his band's often cartoonish image. I won't claim to know how purely autobiographical his songs were, though I'm guessing most began in a fraught memory, an unhappy personal situation, and/or a fuck-up, universalized in the guise of a faceless, lost street punk, a silhouette inside of which millions of outsiders found they fit.

Late in Punk Rock Blitzkrieg, Marky Ramone touched upon Dee Dee's gift. As he tells it, the band was visiting Stephen King in his New England home in the late 1980s when King slid Dee Dee a copy of Pet Sematary; Dee Dee vanished for an hour and returned having skimmed the novel and produced the lyrics and melody to what would become the theme song of the film adaptation. Despite his triumph that night, Dee Dee was beleaguered, strung out and near the end of his tenure in the band. Marky sat with Dee Dee on King's front porch. "I explained to Dee Dee that he was among maybe a handful of people who could pick up a book, skim it, and write a catchy song about it in under an hour," Marky wrote.

I told him he had done for punk what Stephen King had done for fiction—create, from scratch, images, themes, and stories that drew people in because they could relate. Because the songs penetrated to the curiosity, fears, and insecurities people carried around with them but couldn’t put into words.

I can easily see a composite character based on Dee Dee's songs in a narrative film, moving on the streets of the East Village, or a similar cityscape, among hard drugs, friendship, sex, and music, striving for reasons to live beyond opened eyes in the morning and a drug fix by noon. Some of Ramones's later songs for the band—"I Believe in Miracles" and "Strength to Endure," among them—wearily celebrated a hard-won transcendence, yet we know how Douglas Colvin's life ended in Hollywood.

His lyrics, however aphoristic and skeletal they sometimes are, dramatize a really vivid point of view, and suggest so many possibilities for story lines for a kid born "a drumbeat behind" striving to battle addictions and demons to find a place to call home. Here's the storyboard.

now I wanna have somethin' to do…

...

Then I took out my razor blade, then I did what God forbade…

...

Happy happy happy all the time shock treatment, I'm doing fine…

...

You by the phone, you all alone, it's a long way back to Germany …

...

The plaster fallin' off the wall, my girlfriend cryin' in the shower stall…

...

I am an outsider, outside of everything, everything you know, it disturbs me so…

....

Under street lamps I will play, after the school day

When troubles disappear, I feel excitement is here…

...

I'm not an imbecile

Don't treat me like an animal…

...

No one ever thought this one would survive

Helpless child, gonna walk a drum beat behind…

...

I'm making monsters for my friends…