A boy like me

On Gianni Morandi's 1966 protest song "C'era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones"

In 1966, the popular Italian singer Gianni Morandi released the single “C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones,” translated as “There was a Boy like Me who Loved the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.” The story of the celebrated song coming into being is a familiar one of happenstance and luck. At the Italian Song website, Sarah Annunziato has translated Morandi’s tale of the song’s origins which he’d posted to Facebook in 2013. “It was the summer of 1966, when a boy of 20, or slightly older, left Siena with his guitar to find his fortune in the capital,” he wrote.

It was Mauro Lusini. In Rome, in a restaurant, he met the great Franco Migliacci, who had written “Volare” with [Domenico] Modugno. He played him a ballad that he had composed himself, with made up English words. Franco was so struck by it that in five minutes, right after eating, he wrote the lyrics to There once was a boy who, like me, loved the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, a song that would change my career.

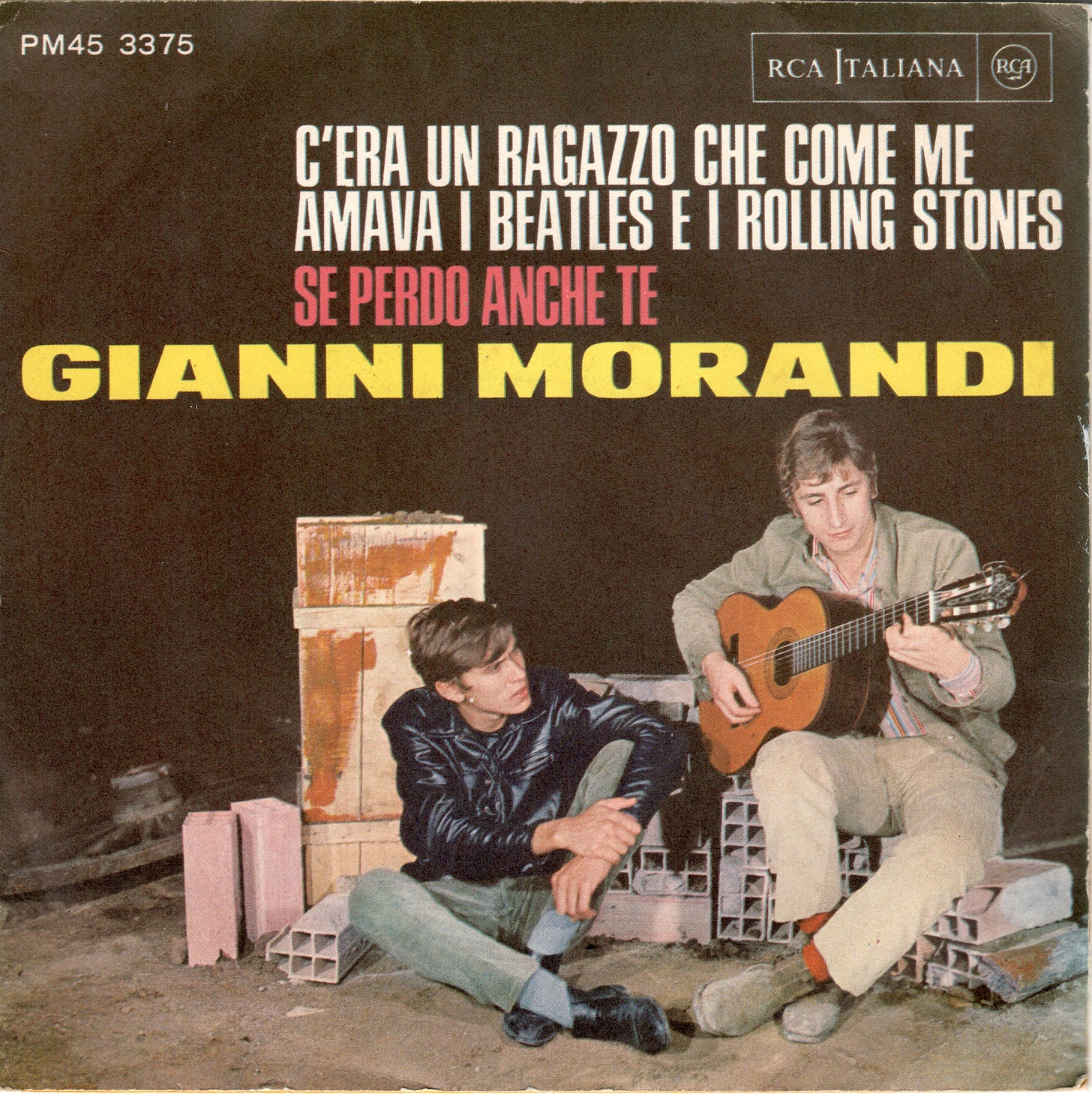

Morandi continued, “The first time that I heard it, it gave me goose bumps. Lusini was recording it and he did not have any intention of letting me sing it. Even Migliacci, my producer, and co-author of the song, did not want me to sing a piece so different, that spoke of war and a soldier killed in Vietnam. In the end, I succeeded in convincing them both to let me record it.” Morandi, with Lusini, premiered the song at the third annual Festival delle Rose in 1966. It was swiftly issued as a single, the flip side of which is an adaptation of Neil Diamond’s “Solitary Man.” (The song also appeared as the second track on Morandi’s album Gianni 4 in 1967).

“C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones” was, indeed, controversial, and was duly censored by RAI (Radiotelevisione italiana), the national public broadcasting company of Italy owned and operated by the country’s Ministry of Economy and Finance, for being hostile toward the geopolitical policies of the United States, an ally. In Proibitissimo! Censori e censurati della radiotelevisione italiana [Forbidden! The Censors and the Censored of Italian Radio and Television], Menrico Caroli (quoted on Migliaccai’s website) wrote that RAI “imposed a kind of ultimatum on the authors: delete [the offending words “Vietnam” and “Vietcong”] or replace them with two absurd substitutes, Cofù and Cefalù.” That those in power at RAI would suggest substituting references to East Asia with innocuous regional Italian and Greek placeholders illustrates just how contentious anti-war sentiment had become across Europe (not to mention the United States’ overwhelming cultural and political influence).

Yet at the live Festival delle Rose performance, Morani rebelliously and courageously chose to sing “the forbidden phrase ‘They told him go to Vietnam and shoot the Vietcong’.” The controversy, Caroli adds, “ended up in Italian Parliament where, in an interjection, a deputy asked how a songwriter dared to criticize the actions of a friendly nation like the United States.” The fuss didn’t prevent the single from reaching number one on the Italian charts for three consecutive weeks in February of 1967; in all likelihood, it helped it.

In the event, Migliacci himself was mollified later by a parliamentary inquiry into the matter in which, to Migliacci’s “great satisfaction,” the Honorable Bruno Gombi, an Italian deputy, “defended our song and deplored censorious intervention. Someone pointed out to me that from then on it would be very difficult for me to see my visa for the United States renewed. But then the Vietnam War ended (or was it interrupted?) and so the ban against me was lifted.” A few years later, as if “to ridicule the zeal of the foolish servants” and “to prove [his] acquittal,” members of the U.S. Consulate asked Migliacci to provide references for the singer-songwriter and composer Lucio Battisti. who was heading to Los Angeles to record. Apparently all’s forgiven in music and war.

I heard “C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones” only recently, when my wife came across it in an Italian language lesson and played it for me. Now I’m deeply charmed by it, and was happy to score a near-mint copy of the 45.

The sleeve is the very picture of youthful earnestness. Morandi, decked out in stovepipe jeans and a snug black leather jacket, sits at the feet of Lusini, who, looking a lot like Rubber Soul-era John Lennon, strums an acoustic guitar: the tableaux’s a hushed pupil/teacher dynamic that feels appropriate. The setting is Bohemian-sparse: Lusini, wearing a sport jacket and desert boots, perches on a stack of teetering cinderblocks; behind Morandi loom forlorn, empty wooden boxes—soon to be tossed onto an out-of-frame fire to keep these two agitators warm, I imagine. Both men are handsome, young, shaggy-haired. The unjust world lies at their feet.

“C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones” is an “electric folk” song performed in a band arrangement, sweetened by a harmonica, stirred by horns, plainly and sincerely sung by Morandi. The melody’s simple, and belies the bitterness in Migliacci’s lyrics. Morandi sings of a friend—it’s unclear how close they are—who just like him, and millions of other young men around the world, digs the Beatles and the Stones. The two bands were, at the time of the recording, poised to revolutionize the pop song (and the pop album), seemingly tuned in, as Ian MacDonald has written, to frequencies inaccessible to the rest of us, soundtracking the daily lives of young men and women alert to changes in the air.

The friend, an American, is hanging around in Italy, likely a stop on a threadbare, poor-man’s European tour. He’s been gifted with the ability, or at least the nerve, to sing, and, guitar in hand, his ordinary looks vanish in the wake of his songs—

All around him he would have a thousand women

if he sang “Help!” or “Ticket to Ride”

or “Lady Jane” or “Yesterday”

—pop music being the international language of communal solidarity (and getting laid). Inevitably, the U.S. draft board crashes the party. The man regretfully hands over his guitar to his friend, and heads for home. The song’s chorus is a response to this unhappy development, and an anguished reckoning with the swift and brutal facts of war:

Stop! with the Rolling Stones!

Stop! with the Beatles stop!

They told him go to Vietnam And shoot the Vietcong

How defanged the song would’ve been with “Vietnam” and “Viet Cong” replaced with “Cofù” and “Cefalù.” How sorry and inept the attempt by RAI to distract listeners from the horrors in East Asia! Meanwhile, the boy’s long hair’s been shorn, his guitar replaced by “a different instrument / that only strikes the same note: ta ra ta ta.” Caroli reports that, with the threat of censorship (and worse) crackling in the air, a careful Miggliachi “thought it best to resort [in the lyrics] to a rhythmic…onomatopoeia that recalled the noise of the machine gun.” Yet when Morandi sang the song and chose to name Vietnam and Viet Cong, the “rat-tat-tat” rang out sharply, the childishness of sounds evoking innocent boys with toy guns playing at war ugly and powerful in its grim irony.

The man is killed in combat, and now has “no heart beat in his chest / but he has two or three medals.”

A political outcry often manifests itself in art, hence the long, worldwide tradition of the protest song. A protest is a response to an eternal injustice within a specific situation, creating a quasi-paradox that illuminates great art as well as great dissent. That is: do I—can I—see myself as a representative of the human condition even in my solitary uniqueness? Holding my handmade picket sign, rallying with a disenfranchised group, marching or rioting, singing a protest song, am I merely an individual or do I ascend to an archetype?

It’s easy to consign a song like “C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones” to its era, another in the large cache of Vietnam War protest songs. The song’s particulars time- and date-stamp its birth, but when I listen now, lifting the tune out from its decade and everything we associate with it, the particulars morph into eternals, the details into silhouettes. Draft board machinations aside, the song could’ve been written in any era since the mid-1960s, the Beatles and Stones replaced with a man’s or woman’s favorite bands or artists. The hair’s still long, the guitar’s still prized and grieved upon vanishing and being replaced by the machinery of war. A decade ago, the journalist Bill Chapin compiled a list of contemporary war protest songs, the differences among them, in style and approach, obscured by their collective anger and concern. The list is growing, a kind of live document to which grievances in song will always be added as we struggle with the poled-desires of peace and strife.

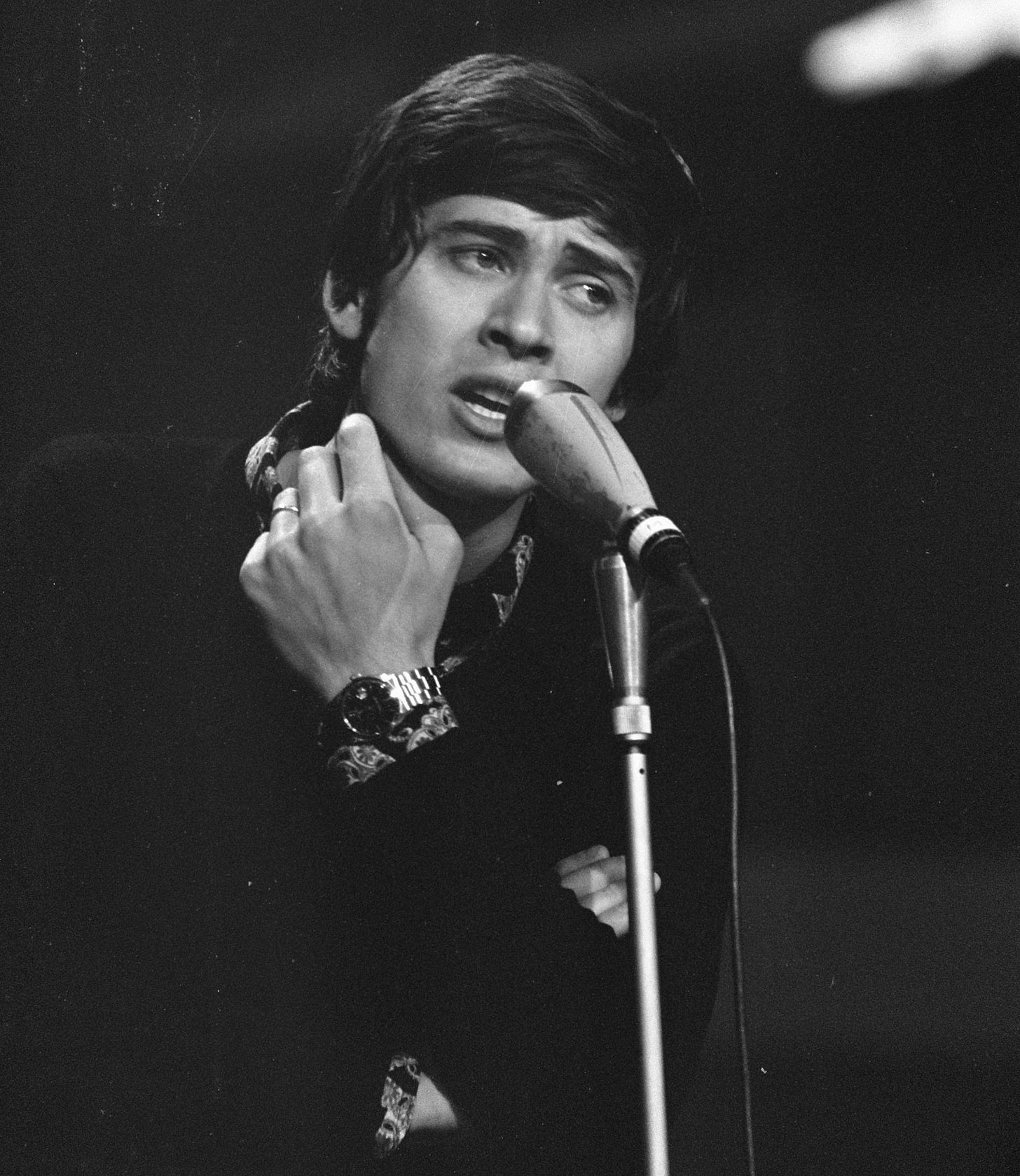

In these undated television performances, the song’s expressed in two ways. In the first video, Morandi and Lusini lip-sync in front of an assembled crowd of kids gazing on sincerely, Lusini emerging from the shadows half way through the song. Though the singers mime ineptly and Morandi seems to shy to mouth the controversial references to East Asia, the song maintains its power in its blend of plainness and indignation, the full stops in the chorus expressing an anger that momentarily clears one’s head.

And here’s Morandi, solo. Judging by the hair and fashions, we’re in the early or mid 1970s. Naming Vietnam, decrying the war, is no longer as controversial as it was, and the intimate acoustic version here makes everything transparent.

What’s poignant in both the studio and live versions, and what will eternally elevate “C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones” from its era, is how we’re asked to sing along—at a Morandi concert spectacle, in our car, in the shower—to the sound of an assault rifle. Lost in a hook, a pleasingly ascending melody, a nonsense sound transcending languages, we hear how a song’s replaced by violence, the violence now a song.

Photo of Gianni Morandi via Creative Commons. Translations of the song lyrics by Sarah Annunziato; translations of Caroli and Migliaccai by Amy Newman

Truly fascinating Joe. Not only had I never heard of the song, I had never heard of the singer! I love being enlightened like this. It's a great song too - which you would hope for with a back story like that!!

Cheers

Tony

Interesting this Italian interlude. In any case, this ragazzo does not have the attitude of this one

https://youtu.be/rLcOyBQK6J4?si=bzs6ne4M_NSRaIiu