Big deal, baby, I still feel like hell

Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers' "It's Not Enough" still cuts deep

I remember where I was when I learned that Johnny Thunders died. I was standing by the record machine in the Union Bar in Athens, Ohio, when future East Village scenester Debra Raffles Trizzini, nee Deb Tripodi, approached me with the news. Thunders was the Junkie Extraordinaire, the Beautiful Wasted Soul, rock and roll personified. Tripodi was wide-eyed with shock, and unsurprised. By 1991, I think we’d all been waiting for the news.

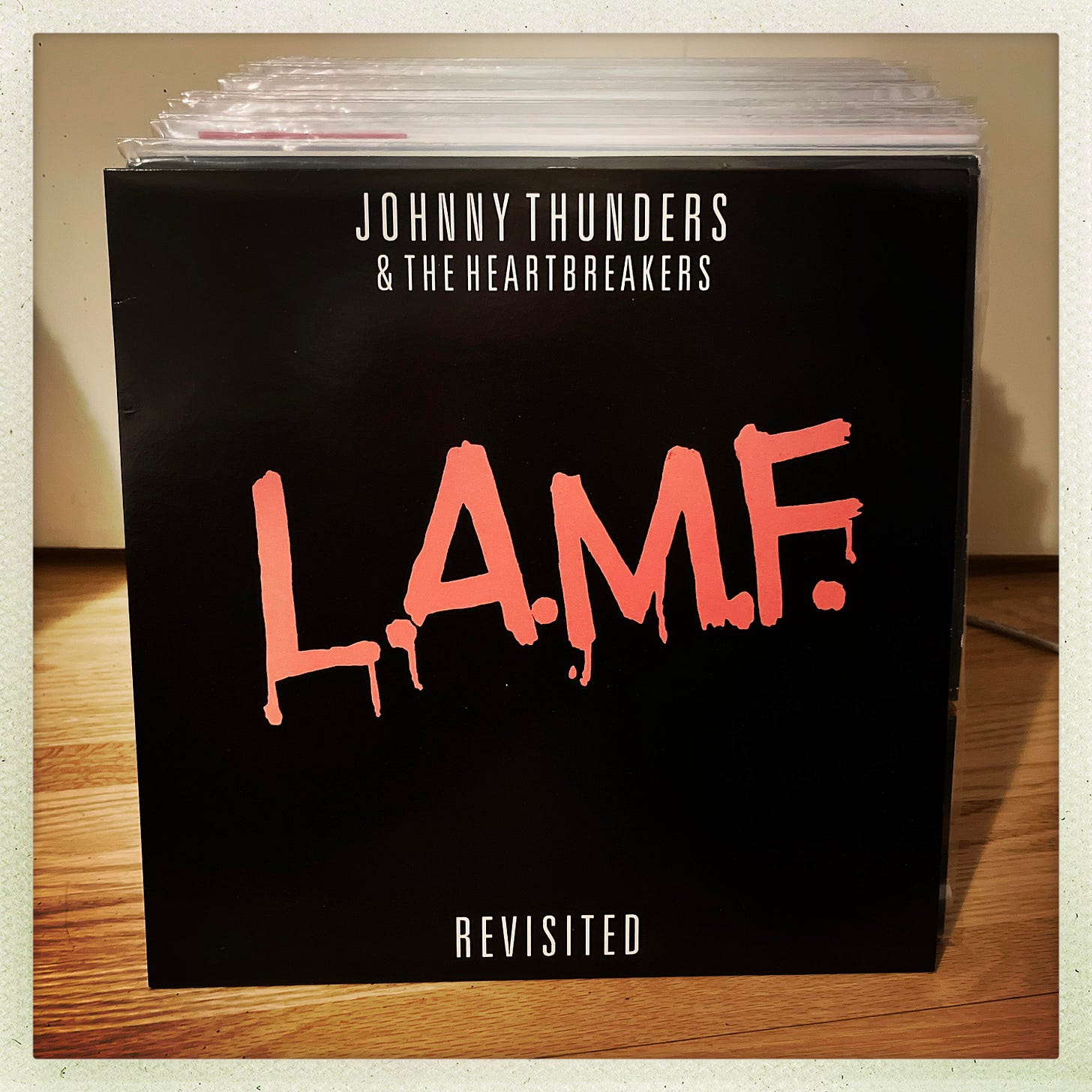

A few years earlier, I’d banged around Bethesda, Maryland and Northwest D.C. in my friend Steve’s dad’s mammoth Pontiac Grand Ville as we blasted the Heartbreakers’ L.A.M.F.. This remains one of my top ten rock and roll memories: killer tune after killer tune, played recklessly yet loosely, blasting from the boom box in the back seat as we careened through the sunny neighborhood, grins plastered on our faces. I’m pretty sure that was the first time that I heard the album, at least all the way through. And I was indelibly marked. Thunders’s guitar solos felt like speed bumps we raced toward and rocketed off from. Several years later, I picked up the album, in its great-sounding “Revisited” iteration, in a cool box set that I could barely afford released by Jungle Records in the late 80s, packaged with a Heartbreakers live album, D.T.K.—Live at the Speakeasy, and Thunders’s playful colab with Patti Paladin, Que Sera, Sera.

By then, Thunders’s reputation had preceded him. Around the time that I was rocking to L.A.M.F. in the streets of suburban Washington, D.C., Thunders was living in Paris, trading on his legend with diminishing returns. In Sweat: The Story of the Fleshtones, America’s Garage Band, I wrote about a sorry event involving Thunders, the kind of junkie theatricality that seemed to accomplish little but add to his already hazardous reputation. Thunders had resolved to ingratiate himself with the Fleshtones, who in March 1985 were enjoying a two-week stay at the Gibus Club in Paris (a residency that resulted in the band’s Speed Connection live albums). Thunders had shown up to the club unannounced early in the band’s stay to jam, and he wanted a return engagement.

The band, feeling as if Thunders was insinuating himself into their scene, tried to discourage him. “Thunders was self-styled rock royalty,” says Marek [Pakulski, bass player], “and it was like we, as this second-generation [East Village] band that we were, were supposed to bow and have him do this. And frankly, we didn’t like that.”… Thunders had wanted to do a version of New York Dolls’ “Pills” and Wilson Pickett’s “Midnight Hour,” and the band was especially keen on keeping Thunders off of the stage as they hadn’t rehearsed with him. “We’d had the set really worked out tight,” Marek says, “a well-arranged set that we’d worked on and that we’d been tuning as the nights went on. We didn’t want to fuck it up by throwing in something we were questionable on.”

Backstage at the Gibus, Pakukski had overheard that Thunders was clean and sober. As it happened, Pakulski was in possession of “really good, heavy-duty brown dope”—and it occurred to him that “maybe [he] could solve [the band’s] problem.” He laid out a thick line of heroin “that would’ve dropped a horse. I was doing a match head and that was enough to get me fucked up. Johnny just snorted the whole thing up and he said, ‘Thanks man, that was great.’ Well, within a couple of minutes he was reduced to a drooling pile of shit. He was sitting in the chair, and his chin was on his chest, and he can’t talk because he had no tolerance, he’d been detoxed.”

The band felt that their mission to detour Thunders had been accomplished. “We hit the stage and we’re doing this kick-ass set,” Marek continues. “In the middle there’s this commotion in the audience.”

All of a sudden we see a corpse rising from the grave coming through the audience: Johnny Thunders is making his way to the stage. How many times have you heard of Johnny Thunders playing on stage so high that he can’t even stand? We had underestimated him, we’d forgotten that if anyone could do it, Johnny could do it. So he crawls toward the stage, staggering and weaving back and forth, and makes it up. In effect the whole thing has backfired and turned into a nightmare because at least if he had gotten up there straight, he could’ve played the song.

The band managed to struggle through an appalling version of “Midnight Hour,” which guitarist Keith Streng remembers as “the worst version of any song ever performed in the history of any type of music on this planet!” Thunders tumbled off the stage after the tune and that’s the last the Fleshtones ever saw of him.

Pakulski’s been clean and sober for decades. He feels no remorse over having doped up a sober Johnny Thunders. “If it had happened today, of course, I wouldn’t have been there to give him the dope,” he says. “But they say ‘There are no victims, only volunteers.’ So he could’ve said ‘No.’ It’s a big world out there and it’s no surprise that he wasn’t able to resist temptation. You're out there in the world and there’s always going to be drugs and alcohol. It’s up to you to not take it.” He added, “I don’t regret having done that.”

Six years later, at the age of thirty eight, Thunder died of drug-related causes (it’s murky) in New Orleans.

I’ve been listening to L.A.M.F. again and to Thunders’s 1978 debut solo album So Alone as I’ve been in a New York Rawk state of mind of late. I also recently watched Rachel Amodeo’s indie movie What About Me, released in 1993, which is available on various streaming platforms. Filmed in the East Village in the late-80s, the movie’s a raw, gritty tale of a woman named Lisa, played by Amodeo, who is unhoused and at the mercy of friends and strangers as she navigates the dicey Alphabet City and neighboring streets. Filmed in 16mm, the film’s a near ghostly document of a city that’s no longer there; that Amodeo and her crew (which included the cinematographers M. Henry Jones and Mark Brady) shot in black and white only adds to the ancient vibe rising from the streets—all grimy, shadowy grays. (A drinking game while watching: take a shot anytime you see a bar, hotel, diner, or bodega that’s gone.) Many indie and alt legends, local or otherwise, appear in the film, including Richard Hell, Deb Parker, Nick Zedd, Richard Edson, Judy Carne, Gregory Corso, Jerry Nolan, Rockets Redglare, and Dee Dee Ramone. (Amodeo’s posted many of their scenes here.)

Johnny Thunders appears, also. Amodeo had asked him to provide some songs for the soundtrack, which he was happy to do; after watching some early footage, Thunders suggested that he might play a role in the film. “His first idea was to play a priest,” Amodeo remarks in a voiceover for the special edition of the film. “Then, a couple of days later he said he thought he should play [Lisa’s] brother, because we were both Italian, and I had a beauty mark in the exact same place that he did.” Amodeo felt that it was brilliant idea for Lisa to have a sibling, to have a long-distance family connection to reach for as she’s unmoored on the hard streets. “So I wrote him in as my brother, and it worked out really well.”

In the scene below, Lisa, desperate and lonely, calls Vito on a payphone. (Drink!) She unwittingly interrupts what looks to be a nefarious business transaction—there are stacked bills, an agitated cohort, a ticking clock—but Vito’s demeanor changes the moment he learns that his sister’s on the line.

“I know you. I know something’s wrong.” It’s family, ok? Thunders’s performance here is wonderful—he’s tender, present, and empathetic. Of course, he looks great. By the late-80s, Thunders’s image was iconic. The piled-up hair, the pallor, the lean frame, the borough accent: Thunders had it all, if all meant the messianic lure toward darkness and dysfunction, to terrible beauty. Vito talks patiently and gently with his sister. Appealingly, he waves off his partner, who’s itching to get moving (“Vito it’s late, c’mon”), because Vito senses something vulnerable in his sister’s voice, the streets behind her, around her, speaking as loudly, and forebodingly, as she demurs. The distance between the infamous, perennially late, fall-down junkie persona—the dupe backstage with the last self-destructive laugh in his pocket—and this considerate and kind sibling with years of family baggage was a revelation. Thunders is playing a role, but his ease and authenticity suggest that whatever he’s channeling is close to the surface of his tracked-up skin. Among his East Village cohort, Thunders steals the movie. Hell is a tad stiff as Lisa’s well-meaning friend Paul, as is Dee Dee as Dougie, who holds forth on a park bench; they both seem aware that they’re acting. Thunders doesn’t. His verisimilitude is affecting, and moving.

And I was led, again, back to L.A.M.F.. I wrote here in 2022 about that album’s anthem “Born to Lose,” how I find it such an expressive and (loudly) poignant performance. As great and renewing as that rock and roll song is, this time around I was pulled to “It’s Not Enough,” which I felt as if I were hearing for the first time. I was listening, without realizing I was, for Vito.

It reads like a nursery rhyme:

You can give me this

You can give me that

You can give me this

You can give me that

It’s not enough

But a dark one. The chords—all two of them—move forlornly, and the melody on top shuffles disconsolately among a few notes. The singer’s tired, yet something in his voice fights back, wearily but with enough self-awareness to help keep the singer’s head from dropping. Money’s green, and it’s all around, but that brings him no solace—ditto the diamonds and rubies, metaphors, maybe, for the trappings that come with success, or that are disguised as success. Figurative or literal, they’re not enough, either.

The song can barely muster the energy to get into the eight-bar middle, where the problem’s laid bare:

Every town I go in

Every street I walk down

I can get anything I want

I just lay my cards down

The performance drags graphically here. The musicians—Thunders on a rawly strummed acoustic guitar, Walter Lure on electric, Billy Rath on bass, and Jerry Nolan on drums—fumble the changes; the impression’s of four guys rousing from slumber in the early afternoon following a long night. The bridge focuses the lens, yet offers no alternate perspective or argument, let alone a suggestion or an answer. The singer can have everything, and yet nothing’s enough. When the problem’s that brutally simple, your options are pretty damn limited. You can read it all as a junkie’s moan, though I don’t know at what point in Thunders’s addiction he wrote the tune. It works best, as many great songs do, as an eternal lament for the hard distance between desire and satisfaction, ideals and reality, getting and losing. Sound familiar? Sounds like a litany that’s existed for centuries.

It strikes a chord. As a commenter puts it over at the SongMeansings site, “The human condition, or the condition of being an ‘American.’ By not having enough he might mean the opposite, always wanting more. Still, he croons like it’s a song about being brokenhearted, and so I wonder if it is both.” They add, “Love the song and the lyrics. The way he sings, ‘i still feel like hell, it's not enough’ makes me cringe. It shakes my soul for sure.” Yeah, Thunders sure sings at the perfect pitch here. He’s naked, sad, too aware of the truths he’s singing to be bitter about them—that was last week. Now he’s stripped of a pose and affect, and he sounds like the guy whose last defense against vulnerability is about to drop, at whatever time of the morning it is. Hard not to imagine that he’s singing the song that Vito is unaware will soon be his to own.

As affecting as Thunders’s singing is here, against the sneering/put-down tenor in many of the other great songs on L.A.M.F., Walter Lure’s playing truly elevates “It’s Not Enough.” His yawning countrified licks in the verses and bridge evoke the singer’s lethargy, but his wandering sixteen bar solo mourns that lethargy. Lure’s leads often took a back seat to Thunders’s signature war-whoop runs, but here Lure stands out with a bluesy solo that recalls Sticky Fingers/Exile on Main Street-era Mick Taylor in its dirty elegance and exhausted grandeur, in the ways it lyricizes and tries to redeem the song’s long afternoon of dejection.

It was not enough. Track released the song as a single, a follow-up to “Chinese Rocks,” but the following year the label went into liquidation, facing debts amounting to £70,000. Track Records pulled the plug in 1978. “I can count on diamonds / Rubies as well / Oh, big deal, baby,” indeed.

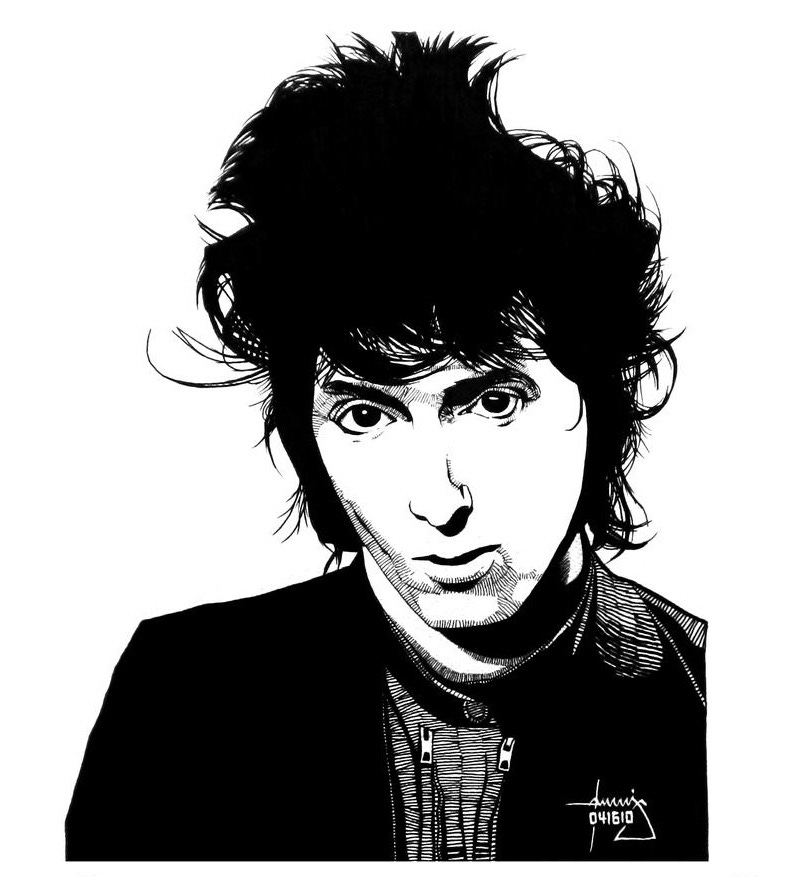

Top image: “DSS No. 18—Johnny Thunders” by gothicathedral via DeviantArt [cropped]

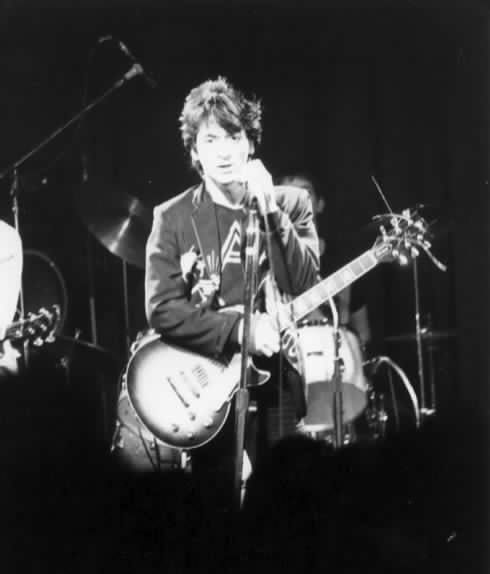

Second image of Thunders: by Einar Einarsson Kvaran, self-photographed (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Damn, Joe! This is great! This is exactly why we do Substack! Thank you -- the most thoughtful read on Thunders I've seen in years!

I just watched What About Me on the Criterion Channel. (The version on Tubi features director’s commentary so you miss most the dialogue. )

All I can say is Wow! Both Thunders and Hell play such sweet, sympathetic characters.

Thanks, Joe!