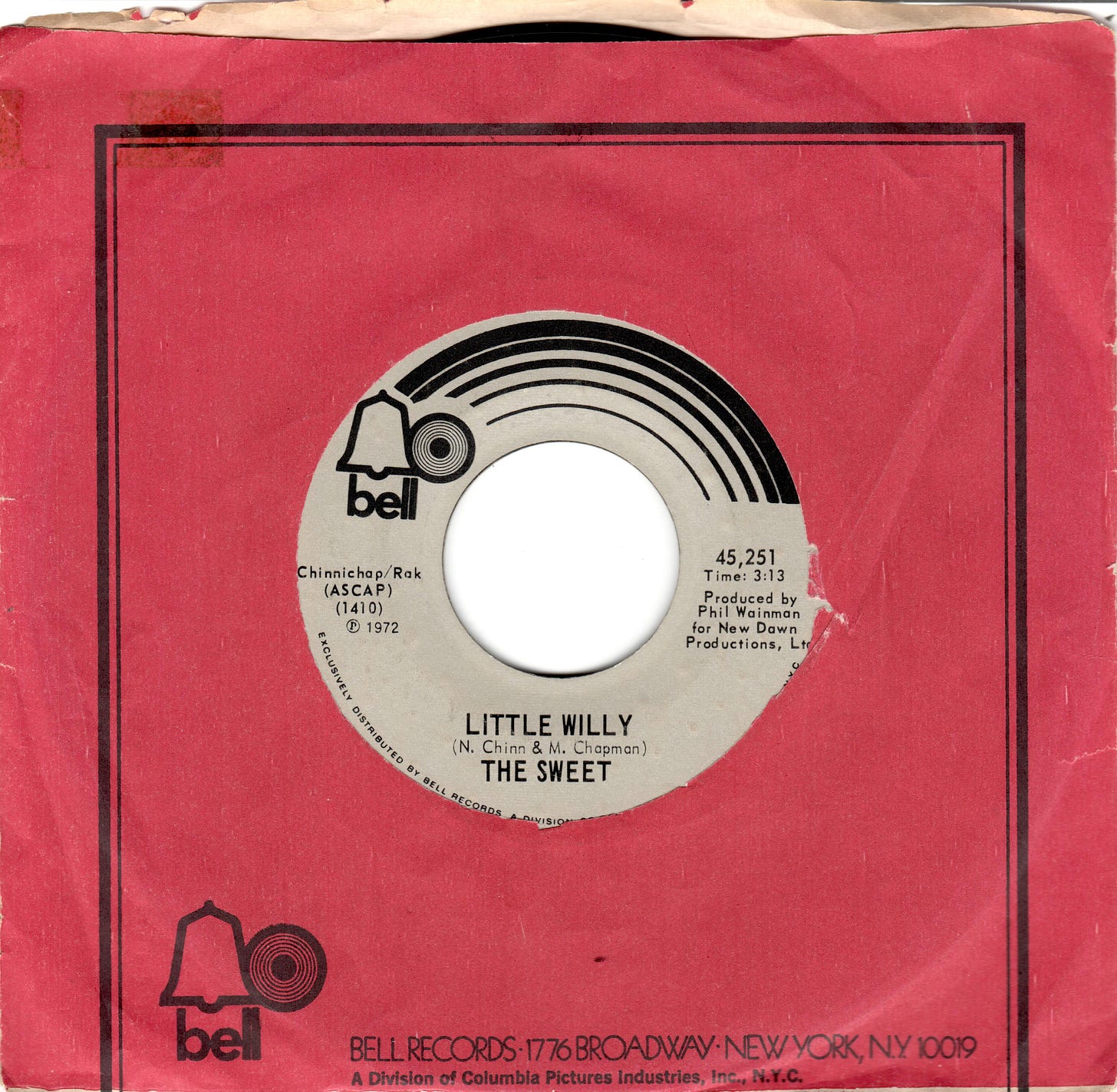

In January 1973, Sweet—then The Sweet—released the single “Little Willy” in the United States. A short time afterward my family bought a copy. A short time after that my older brother sat on the 45 and broke it.

Whether he did this intentionally or not is up for continual debate in my mind’s court of law. I was a kid, he was a few years older. I think we were probably horsing around down in the rec room, and he inadvertently threw himself onto the couch where sat the prize record. (Why we’d tossed it on the couch is another question lost to time.) If I’ve asked my brother at some point for his version of events, I’ve long forgotten his response. I can virtually file the incident away in the Memories, adolescent file, yet sometimes, usually at four in the morning or thereabouts, staring at the bedroom ceiling, I’ll sneak it back into the Memories, adolescent, lingering file, which is stuffed to bursting.

Anyway, the 45 was now unplayable, the incident an early lesson in loss. A year or so later, my best friend Karl would inexplicably move from the cul-de-sac behind my house in suburban Washington D.C. to the far-away Chicago suburbs, and the litany of loss had officially commenced. What I feel now when I look back at the Little Willy Incident is how precious vinyl was, how easily damaged, for good. If you’re a certain age you remember the friend who left their albums in the back seat or trunk of the car on a hot afternoon to warp beyond repair, or the permanent scratches on your favorite single gifted by negligence, or your dog.

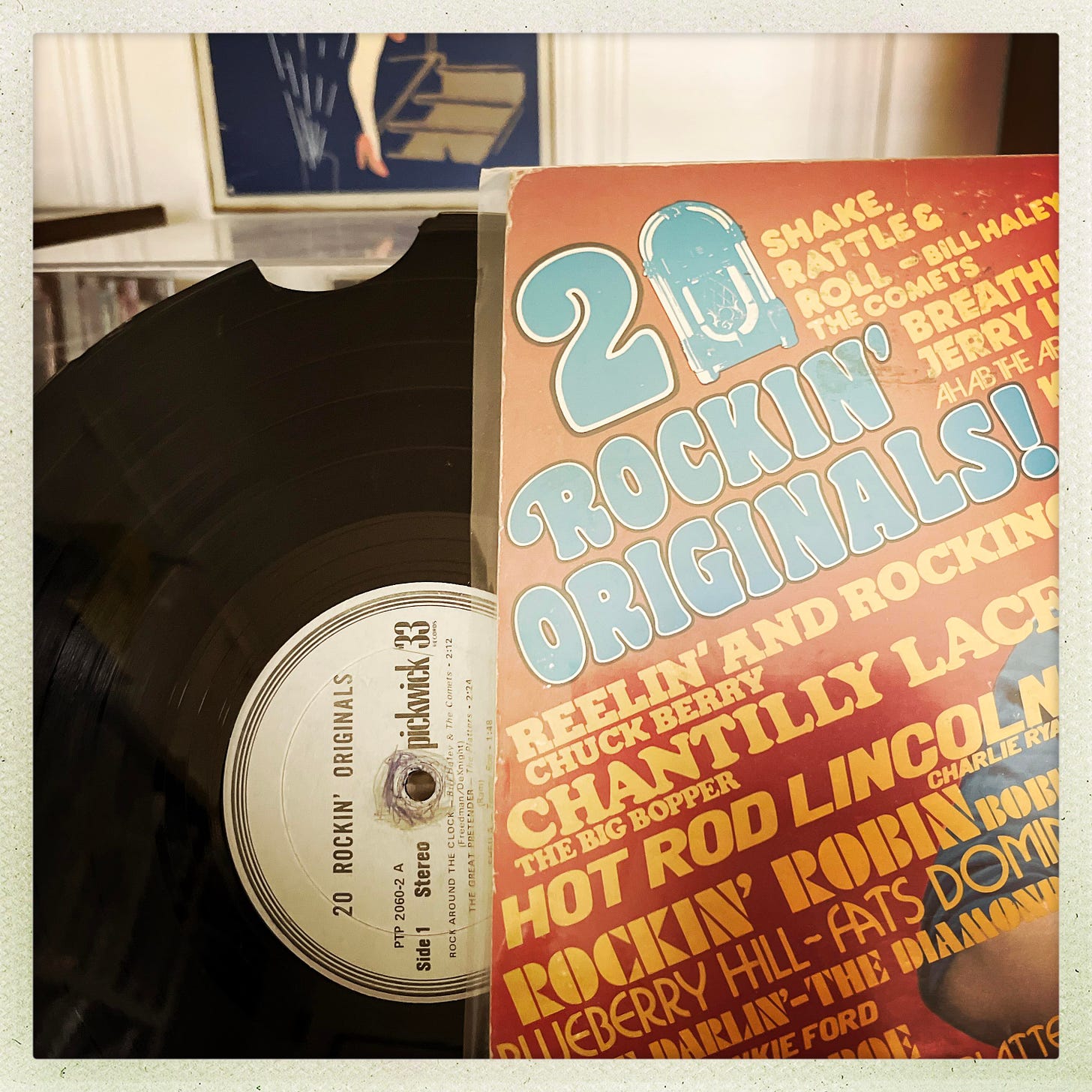

Some of those scratches get and stay there: on the family copy of The Beatles’ Second Album a scratch materialized during the fourth bar in the first bridge of “You Can’t Do That”; I lost that album years ago, but I hear, with a wince, that groovus interruptus every time I play the song, even when streaming, a ghost blemish. Around this tiem someone in the family—possibly me—dropped the second record of Pickwick’s 20 Rockin’ Originals double album and took a big chunk of the perimeter. It looked like someone had taken an angry bite out of the record. For years I couldn’t listen to “Rock Around the Clock.” And I could dig only a third or so of “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” before the needle would plunge off of the vinyl cliff. The agony!

True, I was somewhat mollified by the blonde on the album cover teasingly lifting her jersey over her head, but I digress. My adolescence was perennially challenged by the threat of dropped or stepped-on (or sat-on) records.

A sublime stomp, “Little Willy” was written by Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman, the duo responsible for the Sweet’s raucous “The Ballroom Blitz,” Suzi Quatro’s “Can the Can,” and other indelible tunes from the Bubblegum-Glam Rock era. Session guitarist Pip Williams opens the tune with held, Townshend-like chords on acoustic and electric guitars, building suspense as the house lights go down, before Phil Wainman’s snare smack invites bassist John Roberts to come in and help hold things down. (The personnel on Sweet’s early studio recordings was a complicated situation.) The tune makes cheery work with a variation of the chord sequence in the Who’s “Can’t Explain,” Williams’ half-grinning guitar lines throughout adding some heavy-lidded slyness. Essentially a kids’ dance song, a big, merry bouncy ball, “Little Willy” threatens to leaps from its own grooves as you listen. And for a so-called bubblegum tune, it sounds awesome cranked up, the arrangement a charging blend of AM pop and FM hard rock, the low end and middle dynamics both full and spiky, especially on the original vinyl pressings. (Yes, I did eventually replace the 45, above and below. And for the record, I have no memory at all of grooving to the ecstatically righteous B-side, “Man from Mecca”).

I was a bit too young at the time to debate the alleged naughtiness of the lyrics to “Little Willy”; boys and girls a few years older than me were surely giggling at the title, lighting up recess with pre-teen theories (critics have somewhat misguidedly described the song as “nursery porn”). Instead I think I vaguely recognized the song’s unruly hero in some of the cooler kids in my class, the ones “wearing the crown,” courting and getting in to trouble in “run around style,” and it wasn’t hard to picture their “Mama,” or, for that matter, Sister Nena in the hallways at Saint Andrew the Apostle, chasing after them in vain, driven silly with their “star shoe shimmy shuffle down.”

To be sure, I loved the infectious, gang-hollered chorus, and loudly, ladish-ly singing along to Willy won’t go home…you can’t push Willy round…try tellin’ everybody but, oh no, Willy won’t go home gave me an early, heady glimpse of the lure of rebellion, though I didn’t know the word, only that the song somehow scored my childish urges to say, stay up late, with sheer joy. But anyway I was more tuned into the impossibly fun music, the sublime “Hey down, stay down, stay down down” lift into the chorus nothing less than sonic equivalent of the bittersweet head rushes I’d get wolfing down a cherry-cola Slurpee at 7-Eleven. The little willy willy won’t breakdown chant, the childlike four-on-the-floor stops, so easy and fun to march along with down in our basement, the soaring modulation near the end: the textures of a kid’s long afternoons, soundtrack courtesy of Top 40. “Little Willy” was a hell of a song to have vanish on me.

A few years later, Chinn and Chapman, all grown up, would write “Kiss You All Over,” a big hit for Exile. Suddenly, helplessly, was I paying attention to the lyrics, which complicated the already complicated feelings washing over me on the playground at Saint Andrew’s, feebly following around the scarily, newly fascinating girls in their plaid skirts and white blouses. But back in simpler ‘73, hormonal distractions years away, I was happy enough to only follow the melody and changes in “Little Willy” to simple but eternal pop bliss.

How does music vanish now? How is a song rendered unplayable in this century, as with a literal broken record? Vinyl sales have increased exponentially in the last decade, so kids are certainly still susceptible to older bros or friends sitting on their favorite record, or CD for that matter. Crunch. Yet most people stream music—is a sketchy Wi-Fi connection or a poor data plan now the dreaded source of a song vanishing? Labels pulling albums and songs from Spotify? Copyright takedowns leaving a void on YouTube?

In 2006, Kathryn Harrison wrote “The Forest of Memory,” a terrific essay about being an only child. She describes an incident from her adolescence when she alerted her grandmother to Kathryn’s mother having gone missing on Christmas morning. She later debated whether calling this to her grandmother’s attention wasn’t a grave mistake. (“My mother wasn’t lost—she’d escaped. And I had betrayed her….”) It’s a great read about family dysfunction, the vagaries of memory, and the ways—and the reasons why—we tell stories about ourselves. “Do I remember this night [of her mother leaving] so vividly, with a heightened, almost hallucinatory attention to detail, because it evoked my childhood so perfectly,” she wonders,

or did I unconsciously collect and/or fabricate symbols of my past to assemble them into a story in order that I might contain them within the mnemonic device of a narrative so as not to lose these critical aspects of myself?

Leonard Kriegel’s written that all writers “secretly want to force their past into a container, to make it conform to the image they have of who they are and what they have accomplished.” Though the loss of “Little Willy” didn’t approach the scale of Harrison’s abandonment—is laughably trite in comparison!—it tattooed me in a way that’s hard to rub off, a longstanding family joke that I brought inside. It felt at the time that couldn’t hear a song I loved ever again, that I was a helpless to the capricious winds of Top 40 radio. I was too young to articulate that, of course, but, like all kids, I felt the sensation before the language caught up.

I guess that my lifelong obsession with music and records needed a good tale to spin, an origin story, a rueful morality play involving an older sibling, a guileless boy, and a precious 45. (Kerouac said, “Accept loss forever.”)

“Straight, unpretentious rock from one of the biggest bands to hit England in years,” noted the nameless writer of the “Top Album Picks” column in the July 14, 1973 issue of Billboard. Heralding Bell Records’ The Sweet compilation, the writer described “instrumentals [that] are the most basic guitar, bass, drums arrangements,” adding that “the vocals are unfinished and urgent.” Pulling wide: the Sweet “is part of the recent return to basic roots, but is more of a throwback than a fad joiner. No reason why the group should not be as big as they are in the U.K., with every cut a potential AM hit.”

Alas, The Sweet (Featuring “Little Willy” & “Blockbuster”) would stall at number 191 in the Billboard 200. But the band was only getting started: they’d score thirteen Top 20 hits in the U.K. singles charts the early- and mid-1970s, “Block Buster!” a number one, “Hell Raiser,” “The Ballroom Blitz,” “Teenage Rampage,” “Turn It Down,” and “Fox on the Run” each gloriously detonating at the number two spot. In the U.S., “The Ballroom Blitz,” “Fox on the Run,” and the slightly later “Love is Like Oxygen” were all Top Ten hits.

As was “Little Willy.” “When we started, we used to copy a lot of people,” Mike Chapman remarked to Jonh Ingham in New Music Express in 1973.

Through that, we found our own formula; I now write everything around one chord.

I’ve convinced myself that there are only three chords that exist. And it’s amazing the number of original melodies you can form around three chords.

He added, “We’ve had to do it step by step until now. Right now, though, we just have to make a bleedin’ great noise and keep the records commercial.” I might add to that directive: dynamic, boisterous, and fun. “Little Willy” has never left my head, which, for a long while, was the only place I could hear it.

“The Sweet—Greatest Hits” (detail) by Brett Jordan via Flickr

This essay smells just like a Broome Junior High Teen Club dance.

Lovely stuff.