Looking around for some insight as to why humans feel compelled to create music, I came across an interesting piece from Mic Magazine. In “Science May Have Finally Discovered Why Humans Make Music,” Tom Barnes writes about the work of Leonid Perlovsky, a physics and cognition researcher, who believes that music “is an evolutionary adaptation, one that helps us navigate a world rife with contradictions,” asserting that this is “the universal purpose” of music.

“According to Perlovsky, music’s power comes from its ability to help human beings overcome cognitive dissonance,”

the feeling of emotional discomfort we feel when we learn novel information that contradicts existing beliefs. It's a powerful force for anxiety that affects our decision-making and ability to learn. It's one of the most extensively studied phenomena in social psychology. We all experience it multiple times every day.

Barnes continues, “Numerous psychological studies show that the most common responses to this dissonance are to reject the new information or suppress the old.” However, because this natural impulse might’ve resulted, with dire evolutionary consequences, in humans “never learn[ing] the truth about what’s bothering us,” music exists, and has evolved over time, to allay “the difficulties involved processing conflicting information.” Perlovsky wrote that “While language splits the world into detailed, distinct pieces, music unifies the world into a whole,” adding, “Our psyche requires both.”

As evidence of this, Perlovsky cited a psych experiment in which researchers asked some 4-year-old boys “to rate a group of toys from favorite to least favorite, before asking them not to play with their second favorite.” The kids hesitated; because, as Barnes writes decorously, this “led to some dissonance—”

the children used to enjoy playing with their second favorite toy, but they had a hard time squaring that with their definitive statement that they didn’t really like it. When researchers tried to re-engage children in play, they found that children had totally devalued the toy, suppressing their original love for it.

Yet when this same experiment was conducted while music played, “the toy retained its original value,” Perlovsky writes. “The contradictory knowledge didn’t lead the boys to simply discard the toy.”

I’m skeptical of scientific approaches to understanding music not because I doubt the legitimacy of the work, but because I doubt that science can explain it all. Yet I love this. The complicated looks on those kids’ faces soothed by some music playing in the background. It makes sense that returning to your favorite songs and artists in times of need, when faced with cognitive dissonance of any sort, would smooth the edges, the wholeness of music helping to cohere us when we’re pulled apart by life.

As I’ve written before, I guard against confusing loving a song for thinking critically about a song. And yet I marvel, always, at how love for a song feels as meaningful to me as any idea of argument that one can make about a song. The sublime experience of being transported, affected, moved beyond rational boundaries by music has always felt like a kind of charge to me: to find the right words to explore, to understand why, trusting that that journey toward understanding (even if I don’t get there) is valuable, or anyway worth exploring, in and of itself. Which is another way of saying, God, I love music, and I want you to see why and how. (My subscribers get it, I hope. Thank you all!)

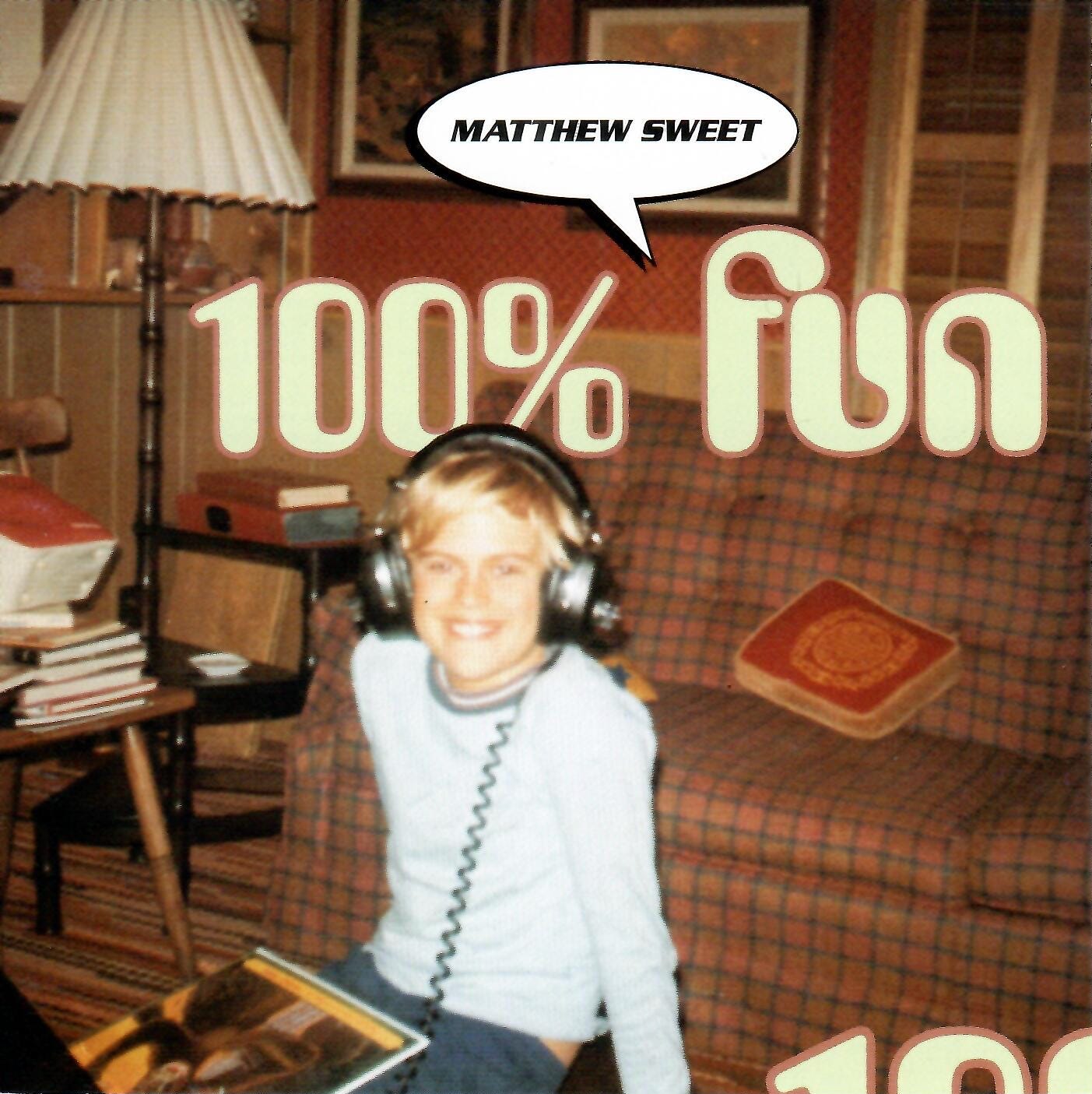

Matthew Sweet’s a musician I dug immoderately in the 1990s and 2000s. (I fell away a bit, and haven’t really kept up with his releases since those cover albums he made with Susanna Hoffs began appearing in the mid aughts.) I’ve been listening lately again and, man, the best tracks from Girlfriend (1991), 100% Fun (1995), Blue Sky on Mars (1997), In Reverse (1999), Kimi Ga Suki (2003), Living Things (2004), and Sunshine Lies (2008) still sound so marvelous, shimmering, bright, darkly sweet, sweetly dark, complex, adult, so evocative of an era that feels very far away from me now. Even as these songs bring me back, where I land as I listen feels like another, somehow sunnier, world.

After reading Barnes’s piece, I was struck again by the sublime “Smog Moon,” the final track on 100% Fun and one of Sweet’s most gorgeous and powerful songs. The singer’s home, but unhappy. The title suggests we’re in Los Angeles or Hollywood; the bridge makes it explicit; Sweet’s aching melody and Greg Leisz’s mournful lap steel guitar make it anywhere anyone’s been heartsick. The song begins with a shushing high-hat lick from drummer Ric Menck as he, Sweet on bass and guitars, and the album’s producer Brendan O’Brien on piano commence a reflective moon-lit stroll, over which Leisz’s lap steel drifts like haze. It’s a late-night mood (“The dark night has the strongest pull”), and a fraught one: the moon’s wavering, obscured by smog, and it burns up there “like a golden lie.”

The singer’s afraid, restless—“There’s a lost man, with a bitter soul / Only for a moment did life make him whole / And while he was, he thought he was invincible”—and he feels like an “afterthought,” destined to believe that he is what he isn’t. That sentiment kills me, and it’s at the root of the song’s deep melancholy: he can’t live his authentic life. Why, we’re not sure; a sour romance or a failed friendship, a test of ideals that betrayed him. I think part of the problem is where he’s living, or, more accurately, where he’s not living. His feet are planted in an anti-home—the trees around him are all cartoons—and he looks up for help only to gaze at something timeless that’s shrouded in air pollution, that “almost looks like it is white,” that’s reflecting his sorrow back to him.

In the bridge, the on-ramp of which is built by a dramatic guitar phrase from Sweet, we learn more precisely where we are, the lyrics—

They’re not your words, but you’re reciting the lines

You don’t mean a thing, but you exist in their minds

How does it feel, when they have turned out the lights?

—dropping us into La-La Land, Tinseltown. When I first listened to 100% Fun I was aware that Sweet was born and raised in Nebraska, and had made a career move out to L.A. at some point, and it was difficult for me not to hear “Smog Moon” as a homesick lament. (Sweet moved back to Nebraska several years ago.) The song hangs its head; its sadness graphic, and its imagery of fake trees and shallow identities emphasizes the placelessness that burdens the singer. I kinda dislike the bridge, as pretty as it is, for so clearly rooting the song in a particular part of the country, but this was Sweet’s truth, and his grief is so poignant that it transcends the composition. When a song’s released, and I hear and love it, and it gets inside of me, it becomes a part of my story, too. Feeling homesick for the east coast for much of the 90’s, I fell desperately yet gratefully into “Smog Moon.”

To this day, the song’s beauty and melancholy and descending melody slay me, even if my take might be at odds with the personal context in which Sweet’s singing. To my ears, the song enacts Perlovsky’s arguments, from an angle. As music exists to soothe the conflicts inherent in being messily alive, “Smog Moon”—a nearly perfect song, in fact a standard in my alternate universe of pop songs—attempts to make some kind of wholeness out of the singer’s unhappiness. He’s in a bind: he’s home, and he’s homesick. Talk about a contradiction, talk about a feeling that’s so common and so eternal. (“I can always feel it.”)

“That song was pretty much passed over in demo form, but [manager] Russell Carter and my parents went manic over it.” That’s Sweet about “Smog Moon” in Billboard, when 100% Fun was released in early 1995. “They kept calling me in the studio, saying, ‘You’ve got to do this song.’ I agreed to do a basic track for it.”

When I went out to sing it, Brendan [O’Brien] came out in the room and said, “There’s something about this song that is really making me excited. You are singing it great. There’s going to be a place for it on the record.”

That place was the final track on the album, coloring everything that comes before it. (“It has amazed me at how popular that song has become,” Sweet said, “even for people who don’t normally like those kinds of songs.”)

The band’s performance is perfect: Menck’s drumming is tasteful and unobtrusive, responding to the quietness of the internal mood; Sweet’s guitar sounds governed by the song’s distracted mood, too; O’Brien’s Elton John-like playing is lyric and supportive, the friendly, understanding guy next to the singer in a bar, or on that moonlit walk. Veteran player Leisz’s lap steel translates the language of the singer’s sorrows into something far reaching, and cutting. And Sweet’s singing is superb. He can soar into his upper register when he needs to, when the song needs it—dig the joyful ache in his singing on the ecstatic choruses of “The Ocean In-Between” from Kimi Ga Suki. In “Smog Moon”’s final chorus, Sweet sings the third repetition of the line “When it’s high up in the sky, it almost looks like it is white” he sounds as if he’s carried by his own urgency.

Years ago, I read an interview with Pete Townshend where he said that he’d been in his home studio recording the harmonies on his demo for “Behind Blue Eyes.” After he came downstairs, his wife told him on how much she liked them. I always loved that idea, of music emanating quietly from somewhere upstairs (I imagine) and wafting down throughout the house, affecting those who, surprised, discover that they’re listening. I recall this story whenever I listen to the final chorus of “Smog Moon.” Something opens in me when Sweet harmonizes on those last lines—it’s poignant and moving beyond measure, a layer of beauty and empathy laid on top of the singer’s sorrow, who now feels a bit less alone.

See also:

So much to prove

Tell it how you like

Image: “Aerial photography of silhouette of city under full moon,” via Creative Commons

100% Fun is my favorite Matthew Sweet album and Smog Moon is one of it's best songs! I think he's been underrated for some of the more quietly reflective songs he's written. I'm also a big fan of "I Almost Forgot" from the same album. It's really a beautiful and layered lyric.

What no Altered Beast (1993)??!! Anyhoo, biiig Power Pop and Matthew Sweet fan here. Yeah!