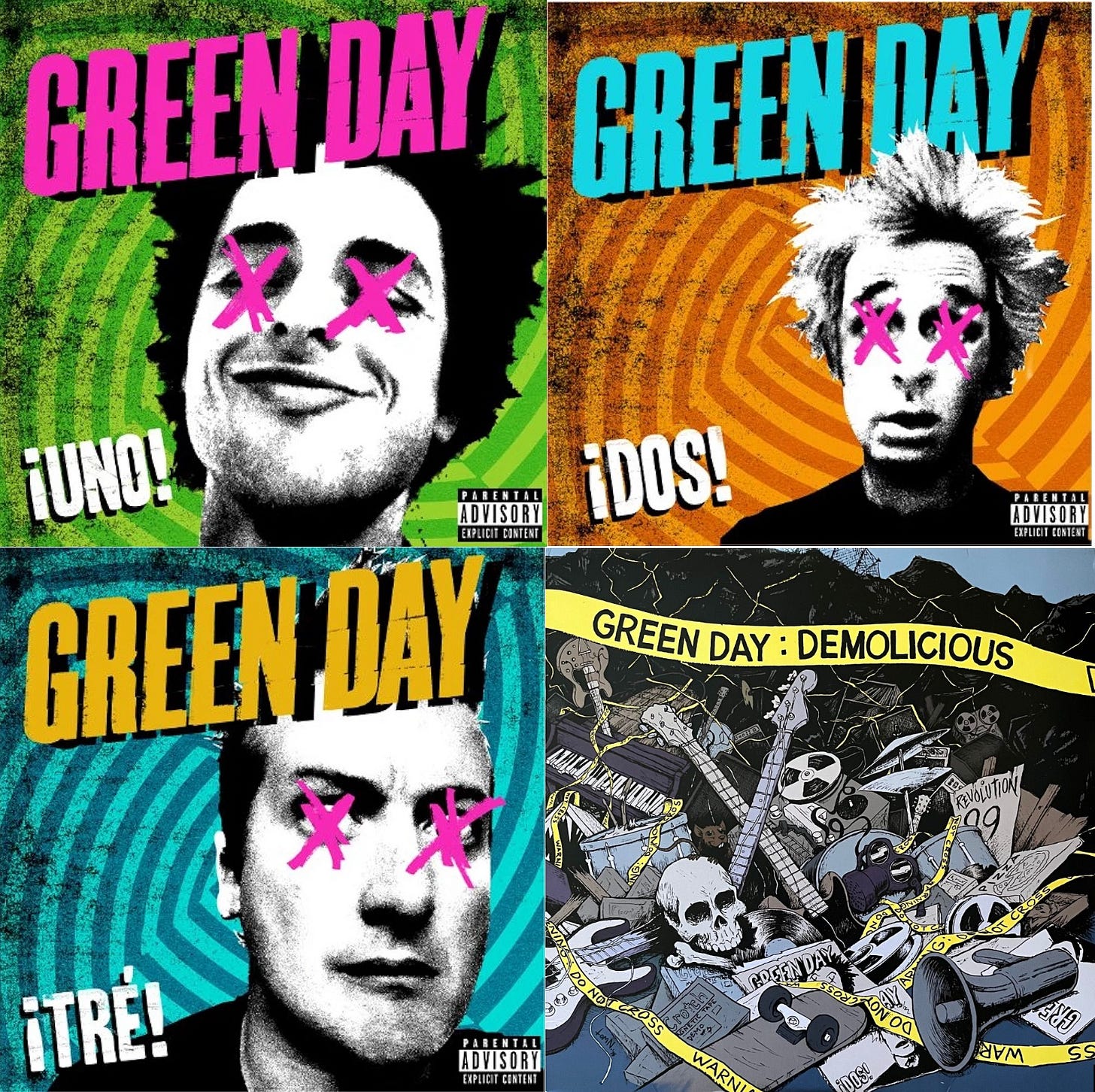

We’re a dozen or so years away from the release of ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré!, Green Day’s impulsive trio of albums that managed to rope in thirty galloping songs. Band members Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, and Tré Cool raved about the albums during promotion, as you do, but consider it cooly these days. Sadly, the era is best remembered for Armstrong’s implosion at the iHeart Radio Music Festival on September 21, 2012 and his subsequent stay in rehab. Armstrong has written about his alcohol and prescription drug addictions and his recovery in several affecting songs since, including “Forever Now” (“If this is what you call the good life / I want a better way to die”) and “Still Breathing” (Revolution Radio, 2016) and, especially candidly, in Green Day’s most recent single “Dilemma” (from the Saviors album, out this month). He also spoke about it recently with Dax Shepard and Monica Padman on their Armchair Expert podcast.

Armstrong’s struggles might’ve derailed the band’s promotional plans for ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré! but in truth those records were patchy, an indulgent gathering of power pop, garage rock, and ballads. The band had decided consciously to write songs against the narrative and “operatic” ambitions of American Idiot (2004) and 21st Century Breakdown (2009). The less complex songs arrived quickly, but the band over-estimated their material; the ethos seemed to be, If it’s short and sounds like Clinton-era Green Day, it’s gotta be good! In hindsight, Armstrong recognized that ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré! “was very much like a writing machine and [the band] just kept going no matter what. Even to the point we’re forcing the material,” in another interview remarking that Green Day had hoped that the albums would amount to “our power-pop Exile on Main Street, and I understand it sounds a bit stiff and the production isn’t great. I love those songs, but a lot of it feels half-baked.” He added, “It was a weird time.”

Throwaway tracks abound across the albums (“Troublemaker,” “Fuck Time,” “Wow! That’s Loud!”, “Angel Blue,” etc.) but there are also a handful of really terrific songs: “Nuclear Family,” “Stay the Night,” “X Kid,” “Lazy Bones,” “Amanda,” and “Ashley” are prime 21st century Green Day, quick, fast, hook-driven rock and roll in touch with joy, darkness, confusion, and dysfunction, resonant anthems for the band’s freak- and loner-identifying fanbase. “Oh Love”and “Amy” (Armstrong’s poignant tribute to Amy Winehouse) slowed things without becoming precious. “Stop When the Red Lights Flash” I dug (and play very loudly) for the killer riff and changes. There are fans who detest and have theatrically disowned “Nightlife,” a mid-paced dance-floor jam featuring the once-and-gone Lady Cobra rapping, but I love the track for its cheery, ballsy attempt at doing something different. (The results are corny, but Dirnt’s bass line slaps. “Kill the DJ” wears a similar groove.) Suffice to say that ever since the albums’ releases countless subreddit members have played the feverish parlor game of condensing ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré! into One Great Green Day Album.

I’m neither a songwriter nor a musician, and so the songwriting process has always fascinated me. As I prose writer I share something with the songwriter—the essential movement from the noise in my head to the noise on the page—but the songwriter works with melody, chords, and keys, where the “music” (if any) in my sentences issues from somewhere else. No one’s walking around singing my essays, even to themselves.

Here’s the incomparable Nick Cave on the mystery of writing songs: “There’s an element to songwriting that I can’t explain, that comes from somewhere else. I can’t explain that dividing line between nothing and something that happens within a song, where you have absolutely nothing, and then suddenly you have something. It’s like the origin of the universe.”

When Billie Joe Armstrong was asked where he thinks his best songs come from, he replied, “I don’t know. I really don’t.”

It comes from somewhere deep down inside of you that you didn’t even know existed. It’s kind of like seeing a shrink or something. (Laughs) There can be a lot of anger, or sadness, or joy, that you had but you didn’t even know you really had—but it can all come out. You feel a connection with it, and so other people can, too. You strike a nerve.

One song on ¡Uno! has real staying power, in part due to its Paleolithic simplicity. “Let Yourself Go” is one of those rock and roll songs that feels as if it’s started before you press Play or drop the needle, you’re just playing catch up. I didn’t pay much attention to the song when the album came out, lined up against the wall as it was with so many like-sounding tunes, but soon after I found myself going back to listen. It took a while for me to realize that even with its leanness and bare bones the song was pretty damn muscular.

Barreling out of the gate with three colossal power chords, the song’s a teetering something that Armstrong has to leap on top of before he can orient himself to what he wants to say. The singer clears his head and his complaints are as old as time: he’s sick to death of this person who talks too much, complains nonstop, takes up all of the space, and who “always seem[s] to be steppin’ in shit.” Everything they say? The singer’s already heard. It's your lie, the he shrugs,

tell it how you like

Small minds seem to think alike

Shut your mouth, ‘cause you’re talkin’ too much, and I don’t give a fuck anyway

Really, he’d rather get punched in the face.

The chorus—such a pretty word for a hollered demand—repeats the title phrase twelve times. If Armstrong didn’t worship 60’s AM radio so devoutly he might’ve gone on for another minute, or five. But in the garage-y spirit of writing off of something like the Who’s “Can’t Explain,” the band keeps things tight. Anyway, the litany continues: they’re screaming in his ear, testing his patience—again. He’s sick to death of their every last breath. You know the type, and you know your reaction, your options, anyway: politeness; avoidance; or letting go.

What does it mean to let yourself go? On MTV News, Armstrong explained that the song’s melody came to him on a walk (“it reminded me of something like Adam Ant”) but then something darker arrived. “It kind of turned into something that sounds a bit brutal, lyrically,” he said, and then pivoted toward two takes on the title phrase that suggests that he’s hearing a different song than I am. Let yourself go can mean “let yourself dance and move and have a good time,” he said, to a knowing nod from Dirnt, or, “There’s the older you get, people that let themselves go. Maybe the girl that’s got a fat ass after high school or something. [stage whisper] ‘She really let herself go’.” Everyone on set chuckles dutifully, but there’s silliness is in the air, and Armstrong delivers the line as if he knows it’s a lame joke, a dodge.

He’s ignoring his own rage. Or am I hearing a different impulse? “Authorial intention” is one thing; where a song lands in my body can be another thing entirely. Armstrong tosses off the title phrase as partly a joke, while to my ears his band’s performance takes things more seriously. (The singer’s agita and need for release are expressed graphically in the post-chorus chant of “Gotta let it go, gotta let it go,” four screeching bars that threaten to tear open the song’s surface.) After a fiery guitar solo—with encouragement from second guitarist Jason White, Armstrong indulged his Guitar God fantasies on these sessions—the song locks into its bridge, a tightly coiled passage where we’ve suddenly gained access into the singer’s addled brain—

Always fuck, fuckin’ with my head now

Always fuck, fuckin’ with my head now

Always fuck, fuckin’ with my head now

Always fuckin’ with my head, and I gotta let go

—a helpless chant that explodes back into the chorus which the songs rides out, exhausted after accomplishing nothing except sounding out its anger. Which, sometimes, is everything.

The ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré! albums have been criticized for a number of reasons, not the least of which being its bland soundscape. “I really wanted the record to be a classic Green Day sound,” Armstrong explained in Guitar World, “but I also wanted to introduce new elements of different guitar sounds—cleaner tones—and to mic the room so you can get the real power of the speakers moving the air to give it more of a live sound. It’s a bit of an AC/DC type of guitar sound, where it’s really powerful but what you’re actually listening to is a clean guitar tone.”

Armstrong told Music Radar at the time that the ¡Uno!, Dos!, and Tré! guitar vibe “is kind of in a new territory—I haven’t really messed with it before,” adding that he’d probably end up using new sound more often. “I love James Honeyman-Scott, early Pete Townshend and Johnny Thunders—they’re some of my favourite players—so that was kind of the sound I was going for a bit more.” Really powerful is in the ears, hearts, and chest cavities of the beholder, but the albums certainly lack fire. Longtime producer Rob Cavallo and the band lost something in translation, the final mix thinning the low end and and softening the middle, the results being anemic.

Green Day certainly knew this, and two years later righted the wrong. “This is how ¡Uno!, ¡Dos! and ¡Tré! would have sounded if we were still on Lookout Records,” Dirnt crowed on Instagram in announcing Demolicious, a 2014 Record Store Day release that gathered demos of more than a dozen tracks from the albums. Rawer, cruder, looser, the demos, as recorded and mixed by Chris Dugan, sound like downed power lines relative to the original albums’ sonic constraint; I prefer many of them to the slicker re-recordings. Fingers on frets, count-ins, amp feedback, studio chatter and exclamations, crude guitar solos, the odd bum note—Demolicious feels alive.

The demo of “Let Yourself Go,” in particular, smokes. Armstrong’s vocal is low in the mix, the impression being that he has to fight harder to be heard over his band—which voices his angst and irritation better than he can. Cool’s floor-tom and snare really kick, and the fangs are properly jammed back up into Armstrong’s guitar. After the song slams shut, Cool’s heard to chuckle to his bandmates, “Do it again!”

There aren’t many discoveries in Demolicious akin to the alternate-lyrics take of “Basket Case” in the Dookie boxset or the metamorphosis of the “Black Eyeliner” demo into “Church On Sunday” revealed in the Nimrod box. But there’s something interesting in the “Let Yourself Go” demo. The lyrics are essentially the same that Armstrong will sing on ¡Uno!, except for the bridge. Rather than angrily accusing someone of fucking with his head, the singer offers something that sounds more like desire:

I wanna live with normal people

I wanna breathe with normal people

I wanna work with normal people…

Vulnerability in the middle of this noise? (Or is it an homage? Some argue that the lyrics are a reference to Pulp’s 1996 classic single “Common People.”) The singer’s either admitting that he’ll semi-gladly join the ranks of the “normal” if it means getting away from this noxiousness—or he’s genuinely desiring some measure of conventional, centered living. The center isn’t usually a place where Green Day songs pay tribute; they’re usually anthems for the disaffected, the bored and the lonely, the fucked up. This strange, affecting passage—I find it surprisingly moving—didn’t make it to the re-recording, replaced there with more conventional Billie Joe Sneering. A pity, as it muddies up things pretty interestingly.

Anyway, grab some earplugs:

See also:

What it's like living in the '20s

Castaways, Part 1

“Green Day in Brazil” by Dennis Ramos via Flickr (no changes)

Thanks for revisiting this record. This particular song is definitely in my single album version of Uno Dos Tre! X-Kid is a personal fave.

Yeah, X-Kid's great, though my fave from Tré is prolly Amanda.