Because I’m a writer who writes mostly about music, not a music journalist, I regularly need to guard against confusing fandom with critical thinking. Certainly, professional music critics wrestle with this problem too, but I imagine that the best ones, some of whom I know personally, can adopt an objective point-of-view with relative ease, akin to sliding into a work uniform and punching the clock.

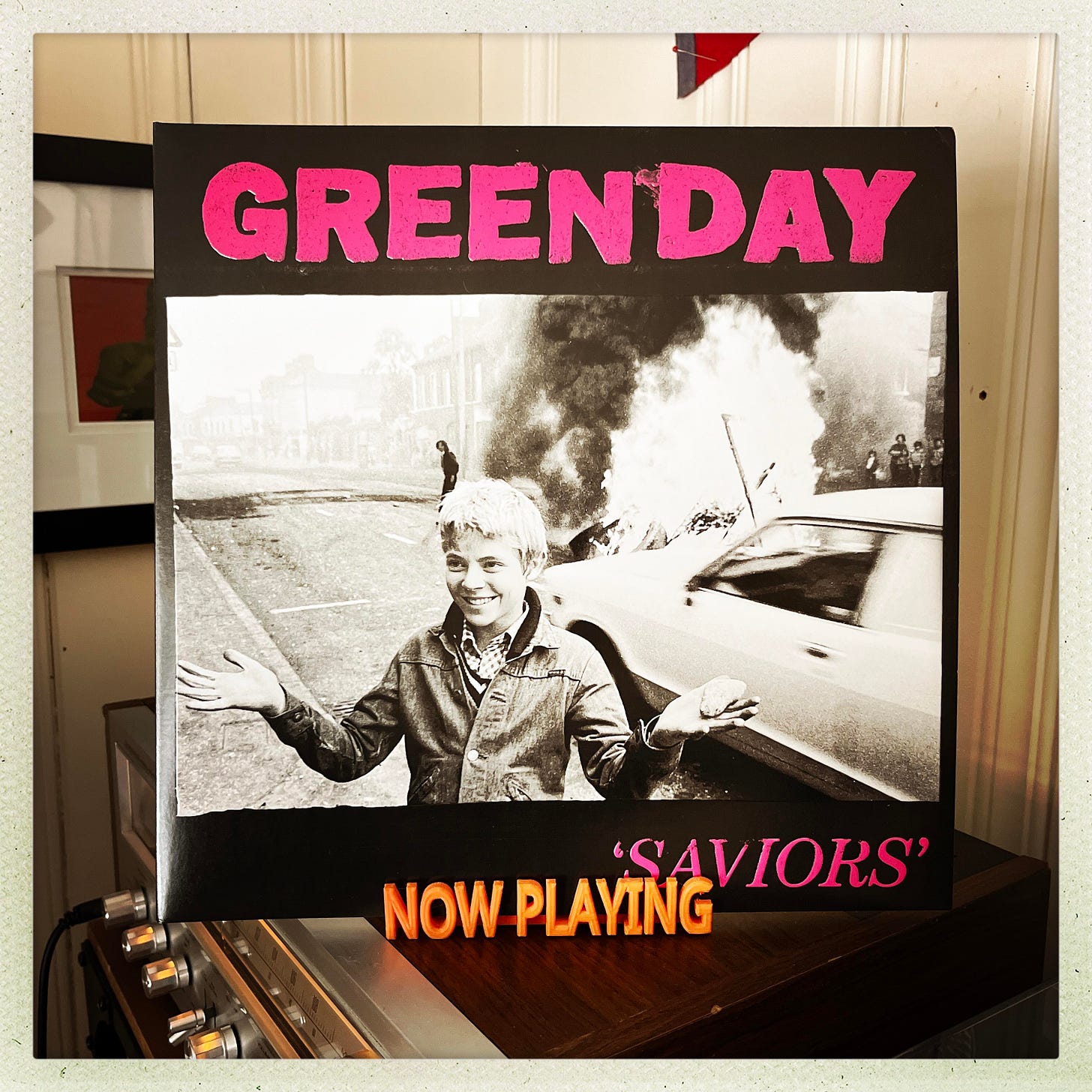

Green Day’s fourteenth album Saviors came out last week. When a band’s as big as Green Day is, I can’t hope to experience many intimate moments in the “life span” of the album. This summer the band embarks on a massive tour of arenas and stadiums—with Smashing Pumpkins, Rancid, and the Linda Lindas supporting in North America—and the nearest I could get to them in a literal sense is a seat in the nose-bleed sections or, where I rather be, the pit, of whatever venue I’d care to drop a couple three hundred to watch a band I love on a giant screen. (I’ve had no luck securing tickets for one of Green Day’s smaller shows they offer up once in a while, in my case the Metro in Chicago last year and Irving Plaza in New York City this year.)

The Green Day Community is so enormous, spanning the world, and the band so far from them, that connections between and among the group and the vast majority of their fans feel virtual. My relationship to Green Day’s music will have to remain in one sense remote, the fate for any most fans of a mega-popular band.

Sometime in the mid-2000’s Billie Joe Armstrong morphed into the punk equivalent of Bruce Springsteen, who once described his own songwriting as “emotionally autobiographical.” That’s the terrain that Armstrong’s on; his juveee, drug-addled squatter days long behind him, his bank account fat, he writes now as a likeness of that earlier, ambitious, hungry kid. He’s long identified with outsiders (in 2000 Green Day respectfully covered the Ramones song of that name) and misfits who feel that they don’t fit in to mainstream society. He still has his finger on that tension, yet the songs he writes now feel as if there’s less at stake for him personally than in the tunes he spat out for Kerplunk (1991), Dookie (1994), Insomniac (1995), and Nimrod (1997). Fair enough. He’s in his fifties now, as are his longtime buds and bandmates, and life has a way of turning down the high-voltage currents of youth. What matters in your fifth decade when your front door closes is different than what mattered in your twenties, when that front door might’ve changed often in a month, let alone a year.

And yet Green Day’s song continue to touch Green Day fans with great intensity. Peruse any of the band’s subreddits and you’ll find testimonial after testimonial from folks whose lives have been affected, sometimes profoundly, by listening to Green Day’s songs. Problem drinkers, drug abusers, those with suicidal ideation, kids struggling with being queer, bisexual, or trans (and sometimes their overwhelmed parents), the terminally unemployed, the Old Punk, the classic loner: they’ve all found some measure of themselves in the songs that Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, and Tré Cool have written down the decades. Their stadium and arena shows, especially to those in the pit or floor, can be ecstatic experiences still.

I think that Green Day is now comfortable with what they are: they are, by necessity as much by choice, a band that creates an enormous spectacle on stage and so writes big songs to match. If the theatrical breadth of their music since American Idiot (2004) sacrifices personal details for communal universals, if those songs can feel formally plain rather than exquisitely arranged, tread in cliché more than once, so be it. They sound big and great live as well as in your car.

I’ve always found it heroic, moving even, when a band in their fourth or so decade can tap into the electricity that shot them around a room when they were kids. (Taste enters here: as I’ve long testified, I’m an apostle of eighth notes, power chords, and melodies spiked with hooks.) Among the knocks against Green Day is that their sound hasn’t evolved much since their first EP (1,000 Hours, released in 1989). Any band whose stock of trade is riffing in three chord rock and roll will run into the dilemma of diminishing returns, as the Ramones learned by the end of the second side of their second album.

Yet what I’ve always found rousing is what the Ramones managed to accomplish with so few chords, the same wonder I feel when listening to Green Day’s catalogue. Rub the surface of the songs on Saviors and their lineage will be swiftly revealed—Power Pop reaching from the Who to Cheap Trick, late-70s melodic Punk, Brit Pop, a nod to the Hives—and this has irked some critics and even long-time fans, who seem overly perturbed this time around by the band recycling their own riffs. I wont litigate the songs’ sometimes-obvious influences here because I don’t care. (There’s a cottage industry of evidence online.) Bands have been stealing riffs and melodies, including their own, since pop music erupted and long before; the Blues wouldn’t have flourished nor been wildly influential without such grabbing (or “biting” in rap and hop hop, two other genres that can’t survive without borrowing). Keith Richards wants the phrase “He passed it along” etched on his tombstone, if and when he kicks. Green Day’s best songs are celebrations of the form, passed along.

And with Saviors they’ve created a loud, spirited, pissed-off, skeptical, bemused, weirdly fun, melodic, hook-y, anthemic clutch of rock and roll songs with which their fans will hoarsely sing along, gratefully finding themselves reflected back in the echo. And there’s that big tour looming in the warm months ahead. In the dead of Winter, Green Day has released the Summer Album of 2024.

Songs group themselves into clusters. “Corvette Summer,” “Bobby Sox,” and “Suzie Chapstick” are affectionate distillations of the band’s record collections. “Corvette Summer” is obvious, borderline corny. Armstrong doesn’t give a fuck. Anyone who’s sung in the car or the shower, or drunkenly in a bar (or in the shower), has written this song—only Green Day actually recorded it:

Get around, I can get around

Fuck it up on my rock ‘n’ roll

Here we go now!

Get around, I can get around

Drop a bomb on my rock ‘n’ roll

Sung as a cool melody against big, supercharged chords, and of course there’s a cowbell. “I don’t want no money / I don’t want no fame / All I want’s my records makin’ / My pain go away” may be a fatuous thing for a millionaire to sing, but such are Armstrong’s pop smarts and charm that fans will be grooving so righteously to the silliness that they won’t notice, or will and won’t care. “Corvette Summer” is a meta rock and roll tune that rocks (if partly in irony), and sounds as if peak-era Cheap Trick goofed around in rehearsal writing a KISS-style song and then years later gave the demo tape to Redd Kross which rewrote it for a b-side. I’m not gonna complain about that legacy. I’m just gonna turn it up.

“Bobby Sox” and “Suzie Chapstick” are Green Day love songs, which means that there are some complications. In “Bobby Sox” Armstrong (who’s long identified as bisexual) courts a girlfriend in one verse, a boyfriend in the next, the song opening up warmly as he sings of things he’ll promise each (though things end gnarled in feedback). The melody is simple, pretty, easy to hop on top of, the arrangement ‘90s-era quietLOUD—or grunge-y power pop, take your reduction of choice—Armstrong’s prime concern being How awesome will this sound sung by thousands of people?

“Suzie Chapstick” feels as if it were written after Armstrong, Dirnt, and Cool enjoyed a hardcore dose of 90’s- and aughts-era power pop (the Push Kings, Wondermints, the Posies, et al) with a big Big Star chorus added to push it over. Strumming among those three chords, the singer’s singing to someone who was there and gone, if only in his head:

Will I ever see your face again?

Not just photos from an Instagram

Will you say hello from across the street?

From a place and time we used to meet?

Everything just grows apart, he complains, and not even the drugs seem to work, but the gently floating melody’s so pretty that it’s hard to hear regret in his voice: this is the very sound of wistfulness. The melody descends for a bit in the chorus (“Outside my window, there is nothin’ but a sky / It’s just another vacant cold and lonely night”) yet not for long, and is soon held aloft by a lovely, Beach Boys-like wordless interlude that sweetens everything to gratitude, for being alive, even for missing out, the bittersweetness drained of bitterness. “Suzie Chapstick” feels, as they’d say back in the day in the corporate office, like a big hit.

Unsurprisingly, nostalgia works its way into Saviors, as well. Back in the late-1980s and early ‘90s Armstrong reflected on his very near-past in “16” and other high school-obsessed tunes. (“When I was younger, I thought that the world circled around me,” he sang in “One of My Lies”—at age nineteen.) On Saviors’s “1981” he rocks a tribute to a nameless teenager in her bedroom in the titular year, banging her head to MTV, a girl who’ll “never see the world the same.” Armstrong turned nine years-old in 1981. I think he’s singing about a crush, a girl who may have ended up like the lonely he’ll grow to write songs for.

In the terrific “Strange Days Are Here To Stay” Armstrong waxes nostalgic again, but for a much closer era: “Ever since Bowie died, it hasn’t been the same” he sings, in the album’s best line. Bowie passed the year Trump came into office, and I don’t need to catalogue what came next. It’s an astute and poignant observation from Armstrong, both fan and social observer. The song’s opening conjures the nervy start to “Basket Case” (Dookie), but now the singer’s less rattled than resigned: “They promised us forever, but we got less.” Armstrong sings that line about Bowie in a melody that rises and falls, insight to reconciliation. The singer looks around and sees only decay, where superheroes play pretend, Jesus quits his gig, where everyone’s racist, and the Uber’s always late. The line “Grandma’s on the fentanyl now” may look like an easy joke, a throwaway. It’s also statistically probable.

Armstrong sings really well on Saviors, in service to the sturdy melodies he seems to have re-focused on crafting, and the harmonies on the album are among the band’s best in years. Absent are the filtered vocals and fizz-pop arrangements on the cartoonish Father Of All Motherfuckers (2020). Dirnt and Cool offer predictably solid support, playing without flash or fussiness and nailing down the songs, or tossing them into the air depending on where Armstrong’s headed. Rob Cavallo’s back in the fold, and his deck gifts and ear for harmony and precision have produced songs that roar but remain in one piece, a radio-, streaming-friendly sound that calls to mind Robert John “Mutt” Lange’s work on AC/DC’s Highway to Hell with its similar-sounding blend of aggression and balance.

There are a few characteristic Green Day rockers on the album. “Look Ma, No Brains!”, a trademark ode to a man-child misfit, and the bitter, darkly charged “Living In The ‘20s” (hyped by some rare tambourine) each detonates righteous riffs and stirring changes, buttressed by catchy choruses and darkly witty social satire. As is his wont, Armstrong slows things when so moved. “Father to a Son” is a poignant series of promises, an earnest ballad that will resonate with bewildered and regretful parents everywhere (and which contains the albums’s second best line, “I never knew a love could be scarier than anger”). A couple of songs on Saviors didn’t catch with me, the title track, “Goodnight Adeline,” and “Coma City,” the latter of which feels like a reject from the band’s ambitious 21st Century Breakdown (2009). The album’s lead song “The American Dream is Killing Me” fares much better in bemusedly critiquing a broken-down, unwell society where family home are razed for condos and the “unemployed and obsolete” stare incomprehensibly at a ransom note.

The standout song on Saviors is “Dilemma,” a mid-paced singalong to the desperation of addictions that Armstrong wrote before he sobered up. His decades-long struggles with alcohol and prescriptions drugs have been well documented, and he’s been honest and forthcoming when discussing them, particularly recently with Dax Dexter on the Armchair Expert podcast. The lyrics in the chorus are poignantly plain—

I was sober, now I’m drunk again

I’m in trouble and in love again

I don’t wanna be a dead man walking

The riff that follows churns away awfully and stubbornly, making clear that the singer’s hopeful resolve will always be nagged by his reckless addictions and obsessions. “Here’s to all my problems,” he sings, “I just wanna drink the poison,” a classic knot of an Armstrong line riding cheer and darkness at once. There aren’t many new ideas on Saviors, but Green Day will likely play “Dilemma” in high-rotation this summer—it was the album’s second single—and among the thousands singing along to the righteously catchy chorus, many will recognize themselves in, and be possibly redeemed by, the words.

See also:

Good read, as always. As to seeing them live, it doesn’t get much more intimate than the Rock Center subway platform, which my wife just missed...

Taking a lot of words out of my mouth, as I am currently doing a GD piece as well. You understand the band more than some (ahem, Pitchfork) and it's refreshing to read a well educated piece on the band that means so much to so many. Thanks!