Rev it up

Chris Alpert Coyle and Scott Sugiuchi’s new book about the Estrus record label, and flashing back to the Mono Men

I lived in Athens, Ohio from 1988 to 1995, an era during which email would arrive and internet message boards would thrive, and yet Athens felt disconnected from it all. A small town in the foothills of Appalachian Mountains, Athens kept alive a ‘60s and ‘70s spirit on its streets, front porches, and bars. Music, when it did arrive, came from jukeboxes stuffed with classic rock, and from townie bar bands, several of renown, that kept alive a folk music/Americana vibe. Occasional out-of-town indie bands would gig at the legendary Union Bar and Grill and at Casa Nueva, the epically good Mexican joint in town, but during my years in town larger touring bands rarely made a stop in Athens, save for the odd show at the Convocation Center on Ohio University’s campus, which, down Route 33 from Columbus, the state capital, home of some pretty great rock and roll bars and theaters, felt pretty remote.

Mail order became a lifeline for me. The top of my head came off when I discovered the Get Hip, Crypt, and Norton Records catalogs in the early ‘90s. (I still lament having to inform an ecstatic Miriam Linna—via a snail mail letter!—that I am not, in fact, related to legendary b-movie strongman-turned-entrepreneur Joe Bonomo.) Though I had little dough in those years—as a starving graduate student, by the end of the month my bank account would often dip into the precarious “few dollars” range—I’d occasionally scrape together enough to put in an order. Having moved to Athens County from the lively, buzzing, music-rich Washington D.C. area, where I’d been raised, I found myself on the far outskirts, culturally-speaking; those LPs and 45s, arriving after the requisite, agonizing 4-to-6-week wait, many of which I own and cherish to this day, were loud, tangible proof that rock and roll still existed.

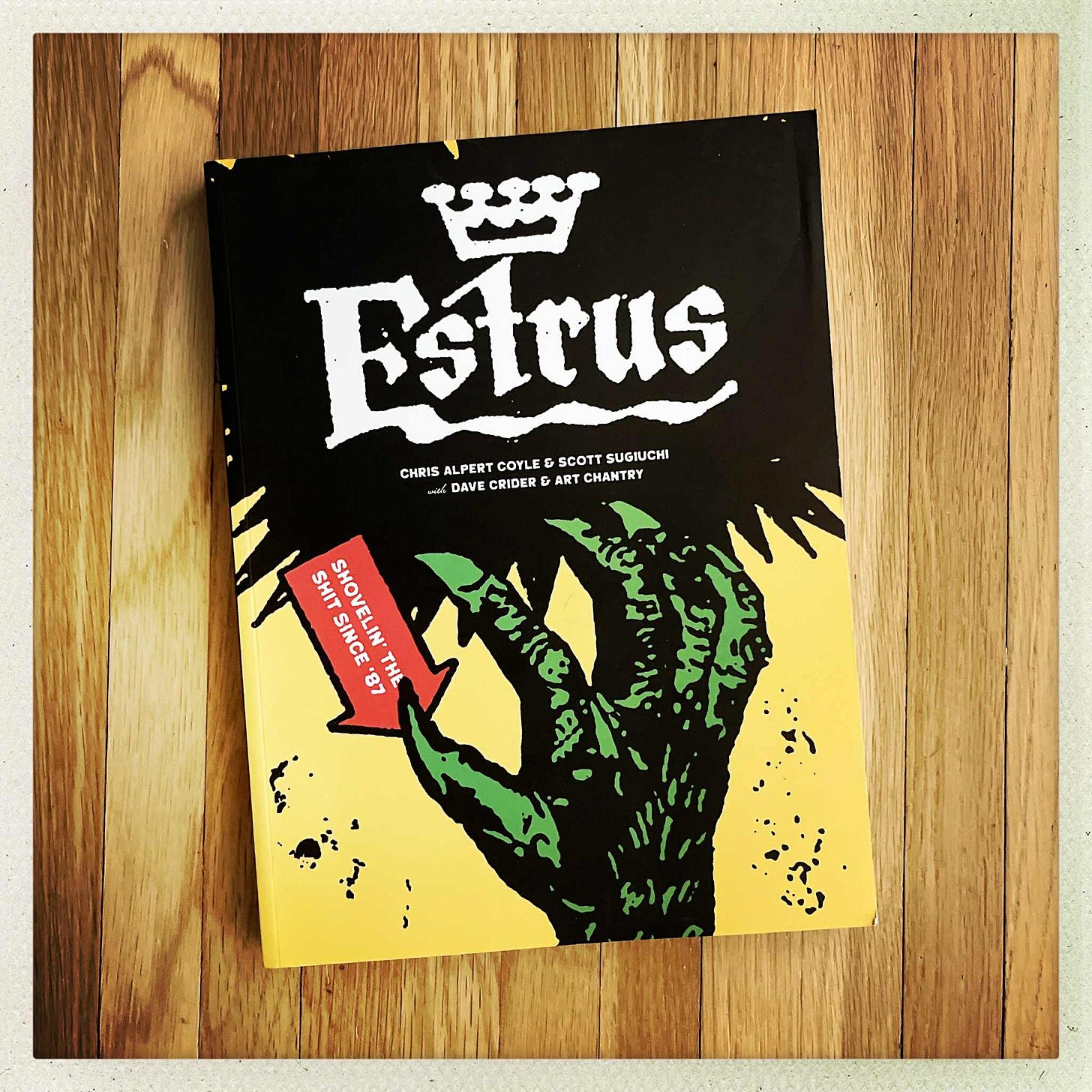

Another catalog I prized in those years was Estrus, making noise in far-away Bellingham, Washington. Chris Alpert Coyle and Scott Sugiuchi’s terrific, 250-plus page oversize book Estrus: Shovelin’ the Shit since ‘87 (Korero Press) recounts the full history of that legendary indie joint, a tale that’s graphic in all senses of the word. Central to the story is the bromance between label founder Dave Crider and house graphic designer Art Chantry, who both contributed to the book. In Crider, Chantry found a like-spirited guy who digs a good beer or four, someone with whom he shared “trashy taste, an interest in crappy music history, a love of forgotten art styles, and a fascination with the history of embarrassing underground American pop subcultures. We hit it off instantly—because we literally spoke the same language.” Chantry learned that Crider had planned on studying archeology in college, but “he’d got sidetracked, becoming a DJ on a country and western radio station in Yakima, Washington (ouch). Coincidentally, I’d studied archeology at school as well! However, I’d been sidetracked by my new job as a garbageman in Tacoma, Washington (ouch again).” He added, “Destiny brought us together.”

With his wife and longtime business partner Becky, Crider worked tirelessly to build and promote Estrus, graduating from phones to fax machine, distributor to better distributor, American reach to European reach, all while spreading the gospel of three- (sometimes four-) chord rawk, sweaty fun, and an allegiance to hairy, lo-fi recordings. Coyle and Suigiuchi’s book lovingly documents the journey, stuffed with reproductions of what feels like every winking advertisement, 45 and LP sleeve, and free tchotchke that the label managed to stuff into envelopes and boxes, alongside terrific photographs of Estrus bands sweating onstage, group histories, testimonials, and tons of hilarious tales, mostly of the inebriated sort. Irony leavened with beery looseness and a half grin was the vibe, as Chantry and Crider conspired to peddle a late-century version of mid-century cool, delivered by a growing ear-busting roster of bands and artists, all fiercely committed to the Estrus Way. 45s, LPs, CDs, label compilations, Sub Pop-styled record clubs—Estrus did it all, frugally yet professionally, adding to the din and mayhem the Garage Shock Festivals, most of which took place at the legendary 3-B Tavern in Bellingham, hosting national and international bands for loud weekends of rock and roll.

Crider and company’s blinkered commitment to their vision of bone-simple, wailing rock and roll produced diminishing returns over time, and, to some folk, elevated cheeky smut and three- (sometimes two-) chord music a bit too highly. Yet I loved a lot of the bands that appeared on the Estrus roster—Huevos Rancheros, Dee Rangers, Man...Or Astro-Man?, the Mortals, the Cowslingers, the Woggles, the Makers, the Mummies, to name only a few among the noisy bunch—many of which recorded for other labels, as well, the norm for hustling indie bands, yet all of which would find a welcome home in Bellingham. Estrus records were above all fun, punk filtered through garage and teenage angst, not though politics or seething anger. If this vibe arguably kept the music in the shallow end, that was still a really charged and fun place to hang out with friends and a case of beer.

Crider and Chantry first met in the late-80s. Their friendship, Chantry writes, has become “one of the deepest and most long-term of my life. What’s nice about getting together with him to do a project is that he and I COLLABORATE beautifully—since we both still speak the same language. When we concept a record cover design or a promotion for a project, we toss crazy ideas at each other until we get excited. Then we know it’s a good ‘un,” adding, “When you get a client like Dave Crider, you do everything you can to hold on to them, because they’re extremely hard to find.”

Dave Crider’s other claim to sonic fame is the Mono Men (sometime referred to as Mono Men), the band he formed, around the same time as the label, with Ledge Morrisette on bass, Aaron Roeder on drums, and John Mortensen on guitar and vocals; Crider howled and shredded, as well.

The Mono Men were the Estrus house band, as it were, and between their first single “Burning Bush,” released in 1989, and their last, the “Hate Your Way” EP, released in 1998, they put out seven albums, two compilations, and nearly thirty singles, split-singles, and EPs. The band hung it up following a devastating warehouse fire in January of 1997 that destroyed the Estrus master tapes and entire catalog, the Mono Men equipment, and Crider’s personal record collection. (Recalling the fire and his decision to keep the label going in Jacob McMurray’s Taking Punk to the Masses: From Nowhere to Nevermind, a Visual History from the Permanent Collection of Experience Music Project, Crider remarked, with characteristic humor, “I mean, if I’m going to stop doing this, it’s because I decide. It’s not because some asshole plugged in a refrigeration unit full of turkeys next to a can of paint thinner. That was the cause of the fire. Had to keep them turkeys cold! They raised wolves! Talk about the Northwest! ‘I've got to keep the turkeys cold for my wolves!’ I mean, can’t argue with that, plus you don’t really want to piss him off too much. Fuckin’ raises wolves and feeds ‘em turkeys! It’s part of the Northwest experience, y’know? Come and visit! You’ll love it in the Northwest! Bring a turkey.”)

A too-brief oral history in Estrus recounts the Mono Men’s career. They emerged alongside the Grunge movement, but never vibed on Seattle, and, by extension, what most outsiders assumed was the region’s sole sound and style. “I know from the very beginning when I started playing music, what made Bellingham different to me was that I really wasn’t paying attention to what was going on in Seattle,” Crider remarked to McMurray. “It’s 84 miles away. Now, in the United States, that’s not a big deal. In Europe, that’s a country. It’s quite a distance. And so I think people would look at it and say that a lot of what happened in Seattle was because they were isolated. Well, a lot of what happened, at least with [the Mono Men], is that we weren’t paying that much attention. We really didn’t care.”

What they did care about was drinking up, plugging in, and playing loud, taking their cues from a very particular Northwest storm kicked up by the legendary Sonics, formed in Tacoma, Washington, in 1960. Estrus’s first full-length release was !!!Here Ain't The Sonics!!!, a boisterous tribute compilation. (I grabbed it soon after its release, and especially dug the one-off Pippi Eats Cherries’ version of “Dirty Old Man,” which ends with a snippet of the Beatles’ “Mean Mr. Mustard.” You must check it out.) The Mono Men contributed a stomp through “The Witch,” yet to my ears their greatest Sonics cover is their ferocious take on “He’s Waiting,” from Boom, released in 1966. Cunningly, the Mono Men slow the song down to a relative dirge, adding a minute to the original’s length. Those sixty seconds only amp up the heat from Satan’s hellfires, adding a menacing edge to an already menacing song. “That’s just about the general thing, about women driving you crazy,” songwriter Gerry Roslie explained helpfully to Miriam Linna in the liner notes to Norton Records’ 1998 reissue of Boom. “It’s all about REVENGE. Like somebody treated you so rotten that you hope they go to hell! I don’t know how much more mean spirited you could get!” He added, “‘He’s Waiting,’ yeah, it’s a threat, like, she’s been so mean and horrible that you hope the devil’s out there ready to get her and drag her away! Ha!”

The Mono Men version—so dark, so scary—updates Roslie’s adolescent half-grin for a later audience jaded enough to need a slow-burn scorcher like this to be frightened again. They flub the words a bit, but it doesn’t matter

“Watch Outside” (from the band’s 1992 debut Wrecker!) is another dangerous sounding tune, a mid-paced lament to a lost relationship which Mortensen wails with sincerity. Not all Mono Men songs are dark— their take on Wally Tax’s “Remind Me” bops, if sludgily—and most, even the desperate ones, are shot through with the band’s trademark humor. They once played a bachelor party at a bowling alley in Bloomington, Illinois (released in 1995 as Recorded Live! At Tom's Strip-N-Bowl), and Mortenson remembers that the evening’s stripper, one Tammy “Boom Boom” Mercedes, stayed onstage with the band for their entire set; “It was kinda weird. We’d be tuning up between songs, and there was this naked gal standing with us.” (Catch the boys at their giggling best in the opening minutes of Doug Pray’s 1996 Grunge documentary Hype!.)

The Mono Men always seemed to me to be having their most fun while playing instrumentals, of which they recorded many during their career. In 1993, they released Shut the Fuck Up!, an all-instro mini album—a couple Link Wray’s, a Dick Dale, a handful of Mono Men originals—in both a censored and an uncensored Chantry-designed cover. (I’ll wait a minute while you hop online.) “WRECKER!”, “Little Miss 3-B,” and “Mr. Eliminator” are all gems, plugging in to the band’s bedrock sonic influences, placating, as the band decorously wrote on the cover sleeve, “those assholes who don’t like the way we sing.”

There was a time in the ‘90s when a couple of shots of Wild Turkey, a few beers (Schaefer was my choice in those daze), and a night at home with the Mono Men blasting on the stereo comprised a highly nutritious diet. If I eat better these days, it’s not because my fondness for Mono Men and Estrus has faded much. Alas, the band is rarely mentioned in music books—they earn cursory notice in Peter Blecha’s Sonic Boom: The History of Northwest Rock, from “Louie Louie” to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and Eric Davidson’s We Never Learn: The Gunk Punk Undergut, 1988-2001—yet they’re fiercely admired by those who dig raw and raucous rock and roll, and among their lo-fi brothers and sisters their best songs stand loud and proud, still.

I caught the Mono Men live only once, regrettably, but what a show it was. The band had hand-picked the Empty Bottle in Chicago as the venue for their final two shows, in December of 1997, a thank-you to Bottle owner Bruce Finkelman, who after the ‘97 fire hosted the Bottleshock festival, a benefit for Estrus. The guys played long and loose at one of my favorite joints, the evening both tempered and warmed by the fact that it was the final time the guys were going to be onstage together. (In the event, the Mono Men reunited in 2006 and ‘13 for some touring; Mortensen died in 2022.) The band was down to a trio by that point—Mortensen has recently split, burdened by the long road and the band’s commitments—and were loud and raw, boozy and fun. As an anonymous reporter aptly concluded in the Chicago Tribune, “Though the sometimes jam-oriented set wasn’t the Mono Men’s tightest, it concluded a torrid career with an unforgettable howl.”

I recall that Roeder’s drum kit was set up near the front of the stage, rather than the customary back position, giving the impression of Roeder sitting on his front stoop with his buddies, welcoming both friends and stranger and offering them a beer. Among the ear-ringing, bleary-eyed memories in “An oral history of the Empty Bottle” published in the April 20, 2016 issue of the Chicago Reader was Allison Hollihan’s. A bassist in Atombombpocketknife and a former Bottle staff member, Hollihan took in (or worked) the Mono Men’s farewell shows at the venue, and remembers, “Everyone was throwing bottles, not cans, at the band at the end of their show. Bruce was very concerned and worried and angry about it. At the end, the stage was covered in broken glass and everything was trashed.” She added, “That was a lot of fun.”

I’ll give the last word to Chantry, quoted in Taking Punk to the Masses: “Estrus was more smartass than bonehead, and it was very sophisticated, very knowledgeable about pop culture and underground culture and crap in America. And so the Mono Men’s style was kind of that bonehead, bachelor pad, hot rodder, garage rock style. I like to think that if Ed Norton and Ralph Kramden had a rock band they would have been the Mono Men.”

You might also dig:

What can you give me?

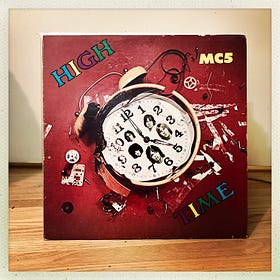

I’ve been reading and thoroughly enjoying Brad Tolinski, Jaan Uhelszki, and Ben Edmonds’s MC5: An Oral Biography of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band. Amidst the terrific stories about their early years and swift, raucous rise as local legends is a fact that confounds me: to a member, the MC5 were disappointed with the performance and sound on their incend…

The song's too simple

In 1985, Dave Hickey published an essay titled “The Delicacy of Rock-and-Roll” in Art Issues magazine, and later included it in his book Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy. In the piece, Hickey, loosely and casually yet highly persuasively, takes down the so-called dichotomy between high and low art. It was a career-long game for him, to deflate pomp…

This can't go on much longer

The week I was born, the Beatles were in the studio laying backwards-guitar overdubs onto “I’m Only Sleeping,” the Who were building the futuristic industrial soundscape of “Disguises,” and the Rolling Stones released their bold new single, “Paint It, Black.” Within a couple of months, the Roscoe Mitchell Sextet would release their avant-garde, free jaz…

Great post! I'm proud to say that Dave Crider was/is my friend, and both he & Ledge spent some formative time working at Cellophane Square, pre-Mono Men & Estrus Records. Fun details here:

https://hughjones.substack.com/p/the-record-store-years-47-bellingham?r=6o97f