Slipping in and out of phase

In his prose and in his rock and roll, Richard Hell wrestles with how to say things

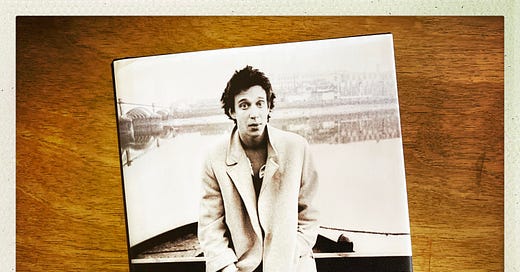

The best passages in Richard Hell’s essential autobiography I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, published in 2013, arrive as Hell pushes up against the limits of language to describe rock and roll. (His memories and writing about the seduction, bliss, and brutality of heroin addiction is also indelible, among the best I’ve read about the cultural/personal/sexual politics of drug addiction. Hell had a lot of fun, experienced a lot of agony, and got out.) Embedded among his startlingly-clear memories of early jobs, early fucking, and early drug use—he kept a resolute journal at the time, to compensate for his poor recall—are scenes where his first band Television (metamorphosed from the Neon Boys) rehearses its early songs. “The power and beauty of it was unimaginable until then,” Hell writes, still marveling decades later. “It can’t be overstated, that initial rush of realizing, of experiencing, what’s possible as you’re standing there in the rehearsal room with your guitars and the mikes turned on and when you make a move this physical information comes pouring out and you can do or say anything with it.”

Perhaps recognizing that that description is lacking, he pushes on:

It was like having magic powers. The ability to create action at a distance. The sounds that came from the amplifiers were absurdly moving and strange, the variety of them so wide in view of the fact that they came from flicks of our fingers and from our vocal noises, and the way that it was a single thing, an entity, that was produced by the simultaneous reactive interplay of the four band members combining various of their faculties. We were turned into a sound, a flow of sound.

Hell recalls “a weird moment of weird revelation” when he vibed that “each moment of a phonograph record being played, each millimeter of information conveyed via the needle to the amplifier to the speaker to the ear, is one sound.” A guitar? One sound. A entire orchestra? One sound. As Television rehearses—and I can see Hell, Tom Verlaine, Richard Lloyd, and Billy Ficca in some low-rent room, with mid-70s New York and everything we associate with it and romanticize outside the grimy windows—Hell intuits, and then understands, that “on each moment we made the sound spray out in arrays we could instantly alter, emanating from inside us and out interplay and our inner beings combined, playing. And the sound included words.”

Then the frustration sets in for Hell, the writer. “All through this book I’ve had to search for different ways to say ‘thrill,’ ‘exhilaration,’ ‘ecstatic’ to communicate particular experiences.” Welcome to my nightmare. What it felt like to first play electrically amplified songs? “It was like being born,” Hell writes, likely aware of the cliché he’s nearing. “It was everything one wants from so-called God. The joy of it, the instant inherent awareness that you could go anywhere you wanted with it and everywhere was fascinatingly new and ridiculously effective. It was like making emotion and thought physical, to be undergone apart from oneself.”

Rock Theory filtered through remembered bliss and mind-expanding drug use, and a bit over-blown. Trying to describe: well, that’s hard work. A few pages later, his head cleared, Hell delivers a far more promising description of the power of rock and roll and its origins. Recalling an early Television gig that co-founder Verlaine had been unhappy with, Hell acknowledges, “It’s true that the band sounded ragged [that night].”

But this was something that had also been said of the early gigs (and often the later ones) of the New York Dolls and the Stooges and the Velvet Underground. It was something that I positively liked in a band. It’s true of the Stones’ Exile on Main Street sessions too, or on some of their early singles, like “Who’s Driving Your Plane?” or “19th Nervous Breakdown.” Another band whose sound I’d always loved was Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, especially on a track like “Going to a Go-Go,” which sounds like it was recorded in an alley, the band banging on cardboard boxes and garbage cans.

Hell loves a racket! And he loves it “when it seems like a group is slipping in and out of phase, when something lags and then slides into a pocket, like hitting the number on a roulette wheel, a clatter, like the sound of the Johnny Burnette Trio, like galloping horses’ hooves.” Then Hell gets a bit carried away: it’s like a baby learning to walk, he writes, a small bird side-flapping a tumble to the ground, two kids losing their cherries. “It’s awkward but it’s riveting, and uplifting and funny. In a way it’s the aural representation of that feeling that makes the first time people feel the possibilities of rock and roll music in themselves the benchmark of hope and freedom and euphoria.”

A bit later, after considering Dee Dee Ramone’s potent appeal as a young man in the mid-1970s, Hell really nails it. Punk epitomizes rock and roll because it “explicitly asserts and demonstrates that the music is not about virtuosity. Rock and roll is about natural grace, about style and instinct. Also the inherent physical beauty of youth.” And remember:

You don’t have to play guitar well or, by any conventional standard, sing well to make great rock and roll; you just have to have it, have be able to recognize it, have to get it. And half of that is about simply being young, meaning full of crazed sex drive and sensitivity to the object of romantic and sexual desire, and full of anger about being condescended to by adults, and disgust and anger about all the lies you’re being fed, and all the control you’ve been subjected to, by those complacent adults. And a deep desire for some fun.

And I love that Hell tacks on this: rock and roll is about being cool, sure, yet “you don’t have to be cool to make real rock and roll—sometimes the most innocuous and pathetic fumblers only become graced by the way they shine in songs.” No Skills Necessary: it’s the dream job ad. “It’s all essence,” Hell adds, “and it’s available to those who, to all appearances, have nothing.”

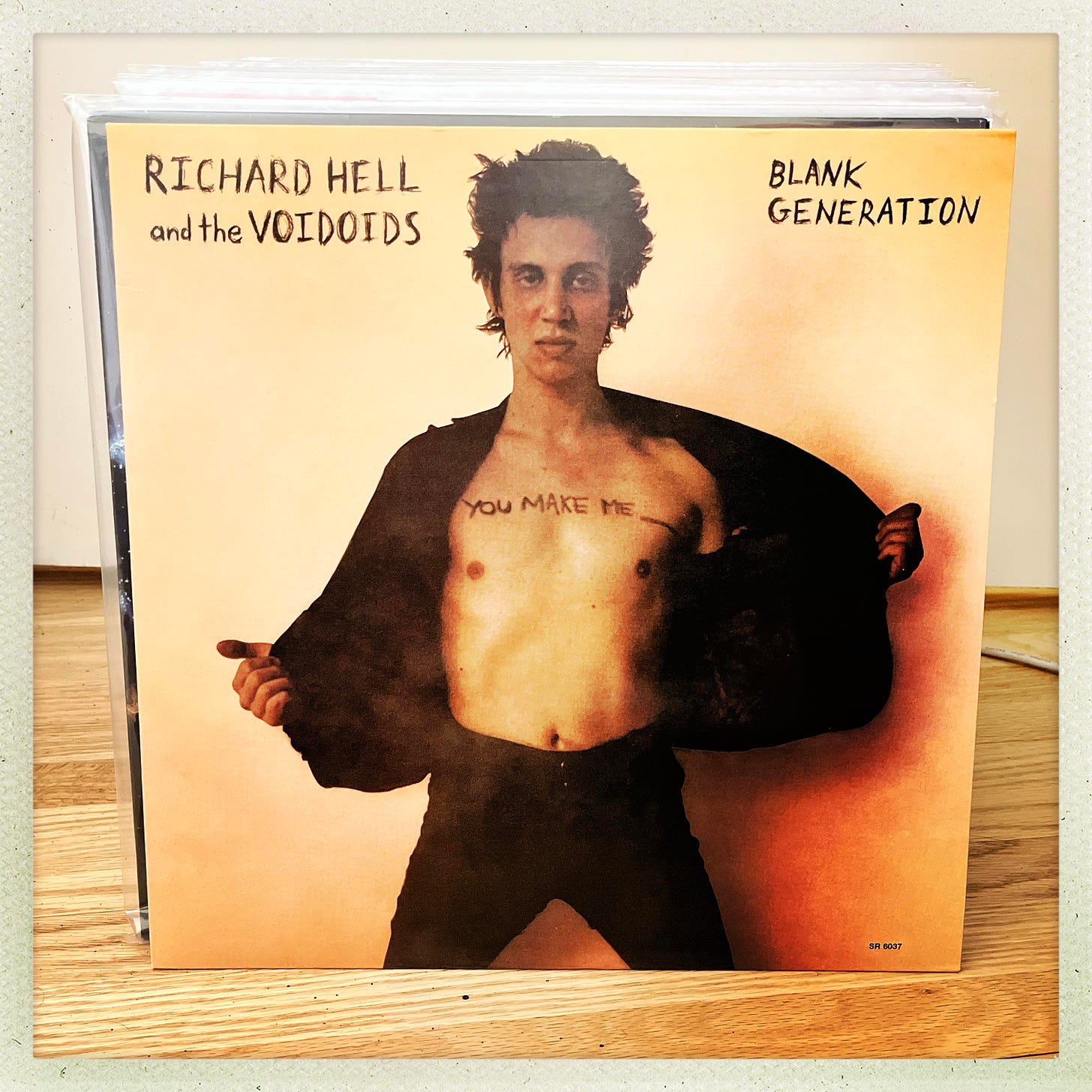

Well, that’s about as good a definition of rock and roll I've read for some time. Inspired again, I pulled out Blank Generation, an album I always loved and one that feels, with my latest listen, like a soundtrack to Hell’s attempts to describe rock and roll. (It always, was, I guess.)

Nervous, jumpy, tightly-wound: the songs that Hell, singing and playing bass, and the Voidoids—Robert Quine and Ivan Julian on guitars and backing vocals, Marc Bell on drums—detonate on Blank Generation sound as if Hell’s somehow converted his frenzied pulse into a music chart. (It was like making emotion and thought physical…) His vocals swoop and quiver, lose control near the top of his range, screech, move swiftly from agonizing to cocksure, and he rarely settles down—he sounds permanently bent on the record. If a voice can have an addled personality, Hell’s does. If a voice can be said to originate in a downed power line, Hell’s does that, too.

“I knew nothing about singing except that it was about emotion, and I had some instincts about the way to convey emotion rhythmically and in tones,” he writes. “For me, singing was like throwing something as hard as I could to stop a threat in its tracks, or stating something beyond a doubt to reassure someone whose confidence I needed, as if everything depended on it.”

I was aware that position and timing mattered, but I relied on instinct and subconsciously absorbed experience to achieve them. And the power came not from volume, in decibels, but from emotion, in revelation. I had to be accurate not in pitch, but in emotional import, of which pitch was a subcategory.

This reminds me of what the late, great Jim Carroll wrote in Forced Entries about singing rock and roll. You can read that here:

Music Without Melody

But, back to Hell: “There was something mystical or at least irrational about the process. I had to trust that I could do it even though it required so much release.”

Throughout the remarkable Blank Generation, Hell, as did many of his street rock cohort, put the lies to virtuosity, and out the emphases on emotional and physical release. Hell sings out of the imperfections of being human, of having been born. “It’s such a gamble when you get a face,” he yowls famously on the title track.

That song sounds as remarkably blazing, dangerous, and desperate now as it must’ve to its first, startled listeners, many of whom no doubt identified with the lyrics even as they were scared by them. “At that point I kind of dropped poetry,” Hell remarked last year to Naomi Fry in The New Yorker, “because I knew for sure that I did not want to get tagged as, like, a rock poet—someone who was intellectual rather than visceral.” Hell allows his band to pick up where his poetry left off: Quine’s exceptional lead guitar lines, snaky, agitated, fluid, precisely so, mimic Hell’s disaffected lyrics and his EKG readings, and the rest of the band complement that pas de deux. There was something tense and jittery in the air in lower Manhattan in the mid- and late-70s—Hell’s book joins the rank of memorably graphic chronicles of that era—and the Voidoids had their collective ear tuned to it.

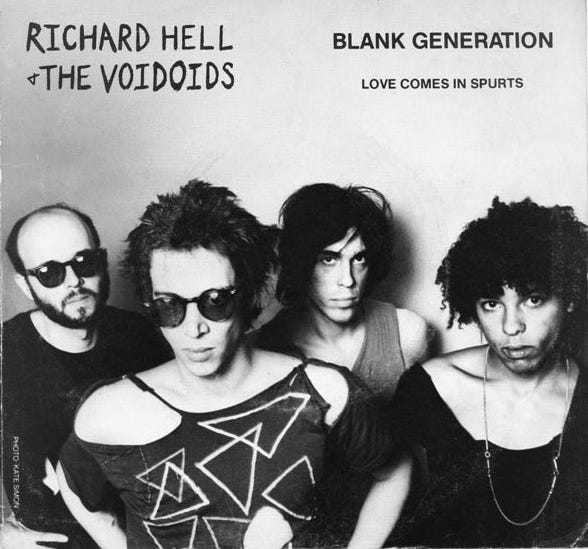

Listen to the impatient openings of both “Blank Generation” and the insanely great “Love Comes in Spurts,” The first five seconds of “Love Comes…,” the first five seconds of the album: a rhythm sections storms up a hill as a lead line on top struggles anxiously in a perpetual riff until an angry drum fill pushes everything through and out into the open. The song’s pulse races, its throat tightens. Everything and everyone’s in a panic. Then Hell enters, climbing that chord sequence with this band, singing about wanting love as a child, “ crazed with devotion,” and then you realize that he’s singing about being a teenager (“I was fourteen and a half / And it wasn’t no laugh”) and the the title, sung angrily in the chorus, becomes both a smutty joke and a lament about sexual politics. (No wonder Elvis Costello felt obligated to tear through it the moment he heard it.) It hurts, and “It murders your heart / They didn’t tell you that part.” Quine’s brilliant solo essays the whole mess, sorting things out, trying to make sense of it.

The guitar playing on “Blank Generation” is equally nuanced, part thoughtful, part unruly, what Hell in his New York magazine obituary for Quine described as “perfectly structured but outrageously wild.” The playing in the opening is taut, solitary, brittle—it sounds like we’re inside the singer’s head. He’s turning things over, working out some knotty problem until, six bars in, a devilish grin crawls across his face, the band lightens up, swings even, and Hell grabs the mic, braying those infamous opening lines. In I Dreamed, Hell, still smarting decades later from a contentious interview with Lester Bangs, is at pains to make clear the distinction between the “and” and the “but” in the chorus of this famous song; the latter suggests that the singer has a choice, can fill in that blank with whatever they want, however they want. Hell sees this as a positive. Meanwhile, Quine’s just pissed off. His solos blend the thick, raw strokes of Link Wray with etched, cerebral frills, brilliantly recorded—cleanly, but with with punch—by producer Richard Gottehrer. As Hell puts it, Quine married “rage and delicacy” into a “pure monster of invention.”

There’s a sense of searching that’s palpable on Blank Generation—in rock and roll clubs, for new pleasures, for the meaning in breakups, for pop songs embedded in post-pop street rock. Even on the cover of Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn’s “All the Way”—a hit for Frank Sinatra in 1957, cut by the Voidoids but left off of the album—Hell wanders, trailing his shaky voice. If you didn’t know the original, the Voidoids’ version sounds as if it began as an earnest attempt to write a pre-Army Elvis number before devolving into parody and never finding its way back. It’s a kind of a stylized inarticulacy, how I hear it anyway, and there’s plenty of that on this tough, fraught album. “Liars Beware,” co-written with Ivan Julian, opens with a single, raw guitar chord struck more than a dozen times before focussing on one note picked rapidly, encouraging the band to come crashing in—a thistle of obscure thoughts that part for a clear idea. The breathless “Oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh”s in the first line do the same thing, move from incoherence to a clear-eyed demand: “Look out liars and you highlife scum.”

There are “Oh oh ohs” on the epic “Another World,” too, where Hell sings “I could live with you in another world, not this one.” He might as well be singing to language itself.

I’ll give Hell the last word: “It was about bringing real life back to rock and roll, because [the genre] had become this stadium thing and all these theatrics and lights and showtime, whereas for me the best music was about experiences people were having,” he remarked to Fry. “It wasn’t just comforting pop music, and it was also not the self-indulgent, endless guitar solos and drum solos or musicians trying to do symphonies. But, instead, it was the driving, expressive, three-minute songs.”

He added, “I didn’t know anything about how these things were constructed when I started out. It was more about an attitude or values of what matters in a rock-and-roll song.”

Middle photo: “Richard Hell & the Voidoids 1978” by fitz via Flickr

Love Comes In Spirts!

Nice work Joe! Of course, you are drawing on some great work... And I will need to read Hell's memoir after this.