I’ve been working on my next music essay for The Normal School about Robyn Hitchcock’s memoir 1967 and his companion album of cover songs released a few months later. (Look for my piece soon!) As if fated, the Soft Boys’ “Positive Vibrations” popped up on Shuffle the other day. I bet that Robyn would have something both whimsical and profound to say about such serendipity.

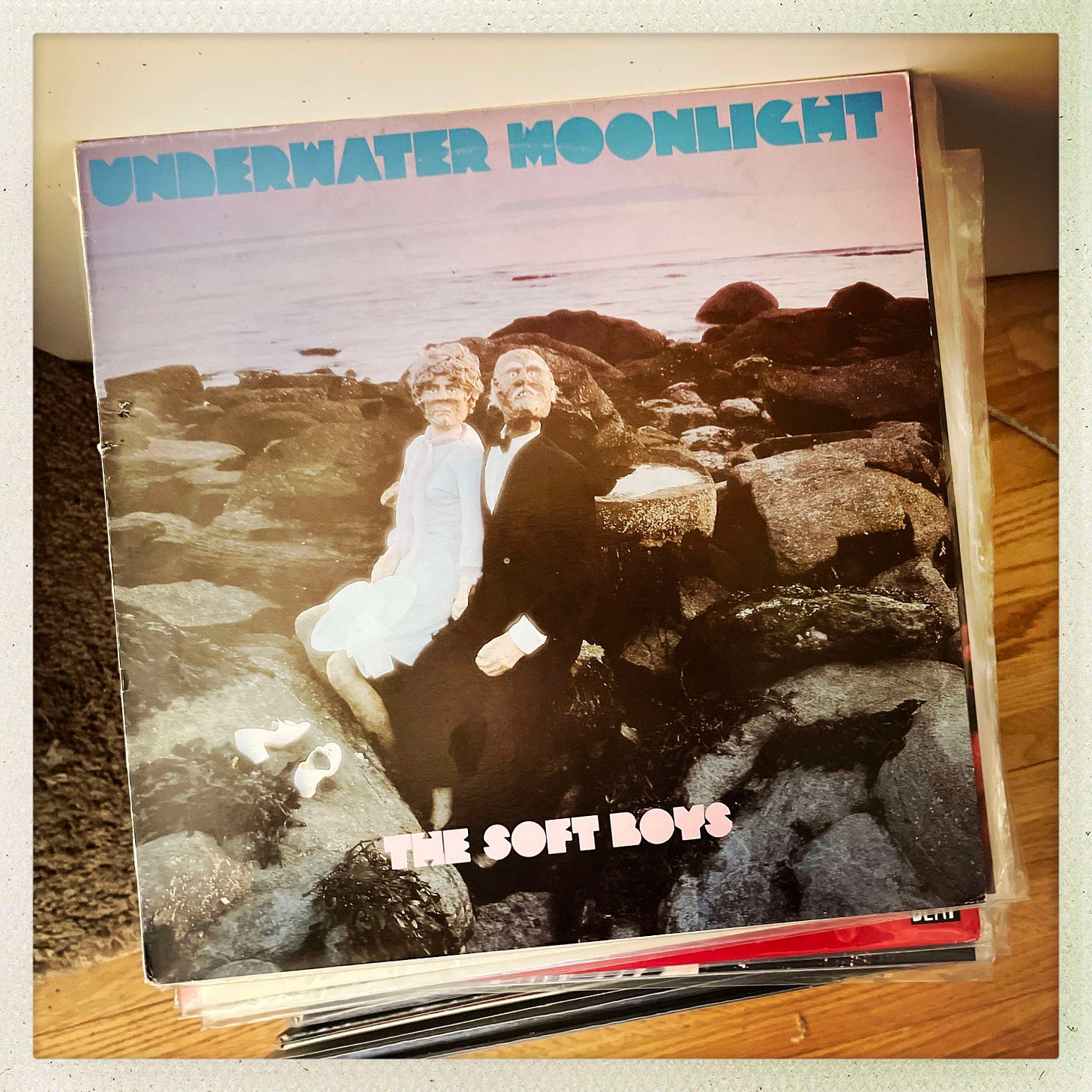

In the event, I turned it up loud. I hadn’t heard the song in a long time, and the gift of randomness only made it sweeter; as if the song playfully tapped me on the shoulder and then ran ahead, I felt as if I were catching up to the song as I listened. “Positive Vibrations” appeared on the Soft Boys’ second album Underwater Moonlight, released in 1980. If heard by the wrong ears, the song might sound almost perversely naive, as Hitchcock, who wrote the tune, sings earnestly about positive vibes shining through creation, uniting all the nations, urging us to forget all about our paranoia (“It’ll only destroy ya”), chiding us for “killing the lamb” as we’re all “still in the plan.” What a waste, he sings.

The song opens with Hitchcock and Kimberley Rew ringing out heart-quickening arpeggios on their guitars as an excited Morris Windsor keeps up on his tom drums; it all gives the impression of watching a sunrise in fast-motion. Matthew Seligman slides under it on bass as the title chorus kicks in in power pop anthemic bliss. By the time the first verse arrives—

There you go killing for peace

Don’t you know

You’ll never get peace anymore?

Just get war

—you’re apt to forgive the shopworn insights because the sound’s so cheery and rousing, the chiming Byrds-like guitar so effervescent, the song believing its own argument. The third verse takes a bit of a left turn (the song was penned by Hitchcock, after all) as the singer sings “Baby, when you do it to me / I feel like oil that burns in the sea / From the top, never stops.” Not sure who/what baby and it are; I don’t want to go the obvious route (the song was penned by Hitchcock, after all) and anyway it all sounds pretty hot, and positive! The song ends with the phrase “vibrations, vibrations” repeated as a sweet, three-note mantra, growing righteous with reverb as Andy King’s smiling sitar laces the sound with period exotica.

“Positive Vibrations” is all over in three minutes. Arriving two songs after Underwater Moonlight’s opening track, the continent-sized menace of “I Wanna Destroy You,” it shimmers all the more in its frank and guileless embrace of positivity and its healing, uniting powers. After hearing it I sang “Positive Vibrations” in my head all afternoon, half the time not even realizing it, as if it were the catchy, feel-good theme song for a TV show about the day I was living—driving my car, doing chores, feeding the cats. Like so many of us these days, I’m looking for any shot of affirmation I can get, of a reminder, sonic or otherwise, that the dark days we’re in aren’t here to stay, that positive vibrations, easy to scorn and laugh at, can do wonders far beyond our ability to comprehend them. Sing on.

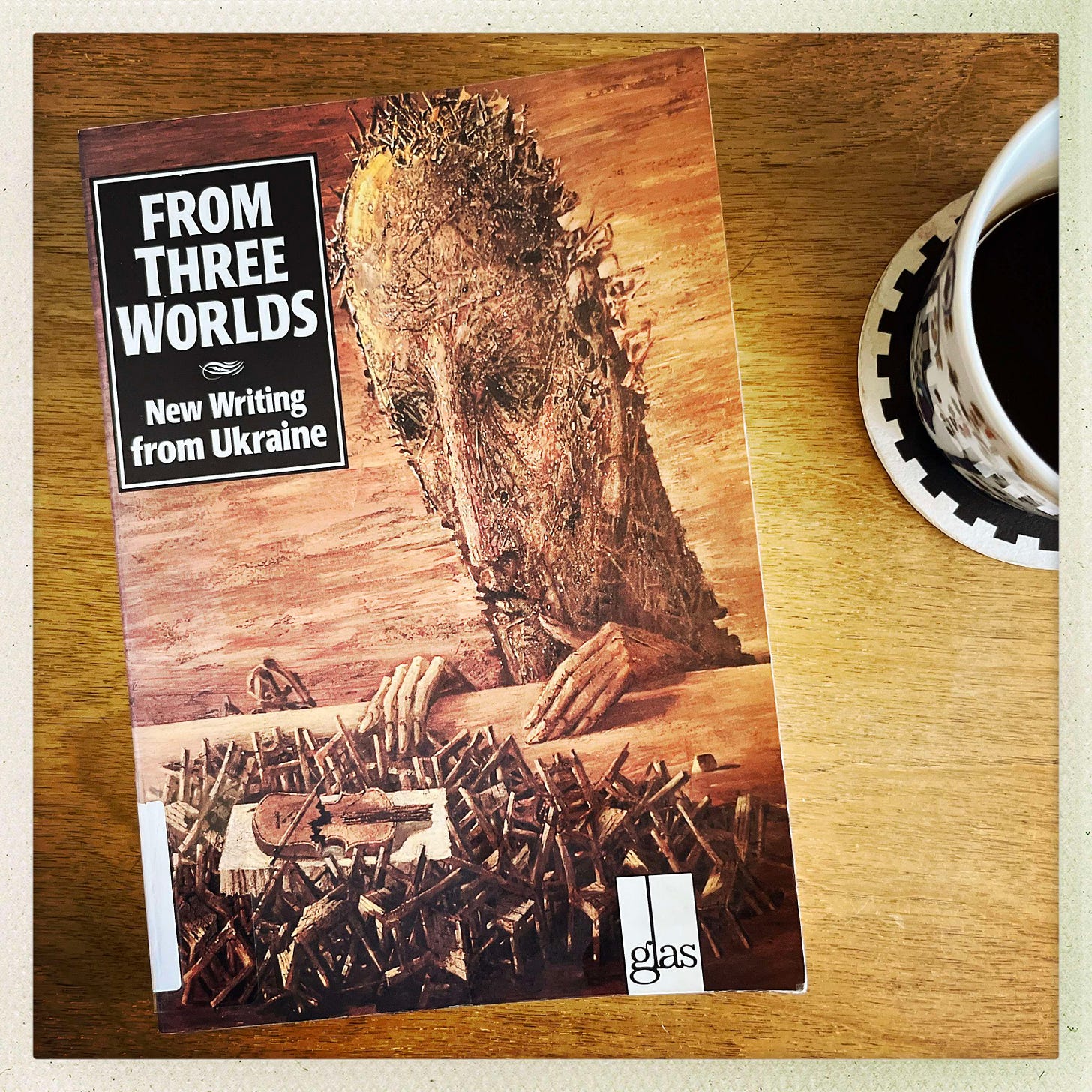

Some more serendipity: a week or so ago my wife Amy brought home a book of contemporary Ukrainian writing in translation. “You might like the opening story,” she told me.

Writer, playwright, translator, and literary critic Volodymyr Dibrova was born in Donetsk, Ukraine and graduated from Kyiv University and the Institute of Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. He taught literature in Ukraine for many years. Since 1993 he’s lived in the United States; he’s currently a Media Content Specialist and Research Reporter at Harvard. In 1991, the year of Ukraines’s independence from the Soviet Union, Dibrova published a book of stories titled Pisni Bitlz (Пісні Бітлз), which translates in English to Beatles Stories. In 1996 two pieces from the book were collected in From Three Worlds: New Ukrainian Writing published by Zephyr Press in conjunction with the U.K./Russian imprint GLAS Publishers.

One of those stories is titled “I Saw Her Standing There.” In just over four hundred words, Dibrova dramatizes an ordinary afternoon of a young rock and roll fan in Soviet Ukraine, ordinary in that the boy’s desire to hear music is thwarted at every conceivable level by the Kremlin. The narrator’s in his fourth year of high school, friends with a boy named Okeksandr who can play some guitar and who’s taught himself a few numbers to play. One day Okeksandr recorded those songs “on those thick old X-ray films you could make at the DIY record studio over on Red Army Street, not far from the public baths.” There, we learn, one could record pop songs (chosen from a list of “Folk songs. Amer.”) or “just the sound of your own voice.” The owner of the studio had promised the kids that he’d record “some ‘beetles’ or ‘beetniks’” songs for them the next time they stopped in. “Even our papers were full of them,” the narrator says of Western beat bands, “how they smashed furniture and paraded about with toilet seats round their necks.”

The boys arrange to head to the studio a day or so later, and the narrator’s running late. “I was kicking my heels, waiting for the tram. At last it poked its nose round the corner, crept out of the side-street and rumbled down toward me.” The tram was twenty yards away when something suddenly exploded under its wheels “with a bright burst of sparks. The rails were streaked and a stench of sulfur filled the air.” Some juvees must have thrown matches under the tram, he figures. He’s about to hop on when “this interfering guy” grabbed him by the collar and dragged him down to the police station, “where a sergeant and a plain clothes cop threatened me with prison if I didn’t write down exactly what had happened.”

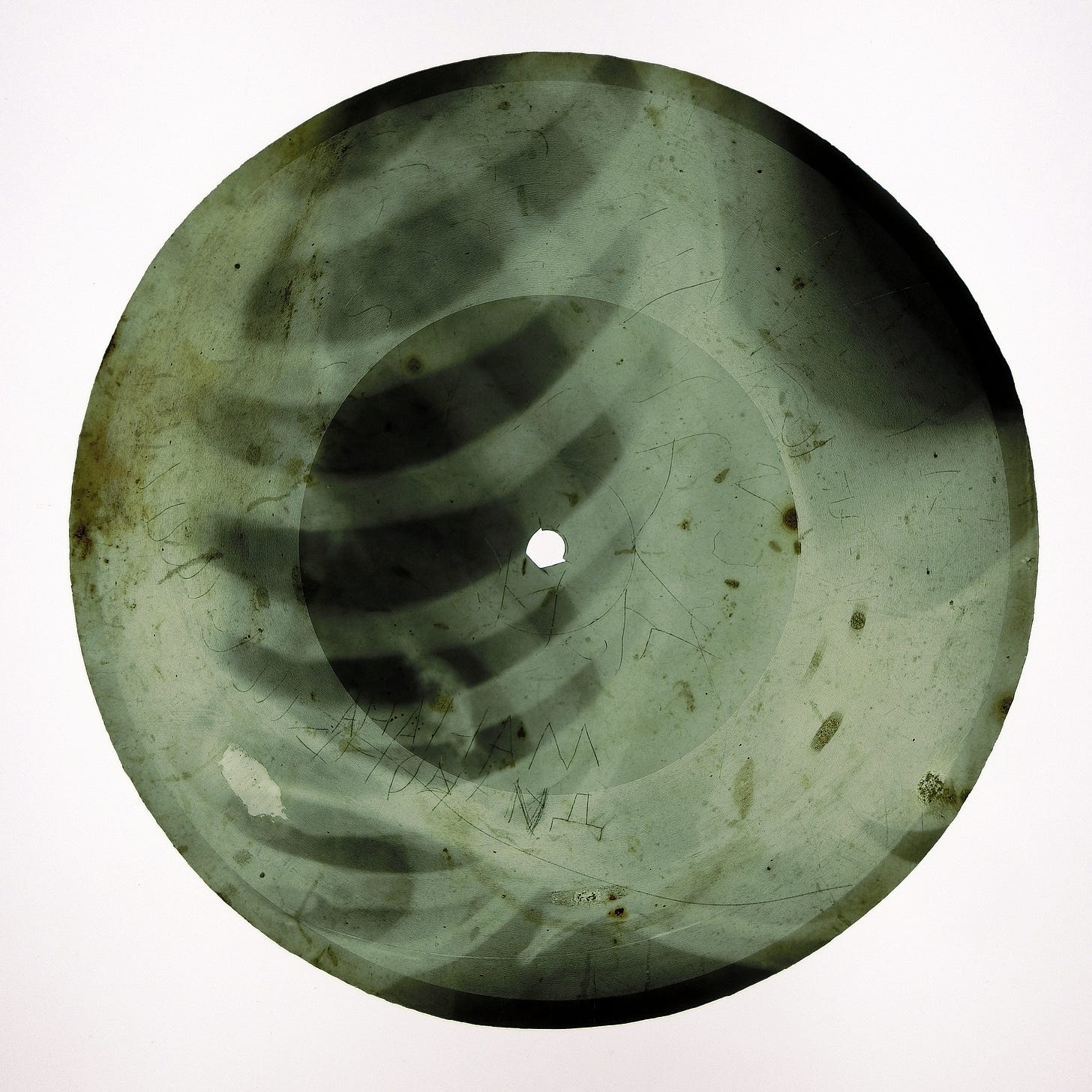

He’s sprung from the station, but not in time to make it down to the studio. Sometime later, back at Oleksandr’s, he studies the new X-ray film recording that his friend had brought home. Oleksandr’s purchased a new needle on his old turntable, and “as soon as it touched the record those X-rayed ribs and bones began to crackle. We heard the sound of eggs breaking frying. The record went round and round, picking up speed.

“Gnash, grind went all our hissing enemies.

“Moan, groan, hummed all our tongueless martyrs.

“Then all of a sudden, it came at last, calling out—One, two, three, four!—the cheeky cry of freedom.”

If you’re unfamiliar with ribs recordings, you can be forgiven for thinking that the spooky, spectral image of X-rayed bones rotating and crackling on a sheet of disc-shaped plastic was something out of a particularly surreal Robyn Hitchcock lyric. But the image is quite literal. As Dave Tomar wrote recently at Music Influence, ribs records, “sometimes also called Bones Music or, roentgenizdat in the native Russian” was “a contraband recording pressed into a used x-ray sheet.” In mid-century U.S.S.R, when “the listening habits of Soviet citizens were strictly regulated by the Kremlin, Ribs Records proliferated on the Russian black market.”

“Basically, ribs records are sheets of discarded x-ray film plucked from the dumpsters outside of radiology clinics,” Tomar explained. Fantastically, in a kind of poor man’s Rube Goldberg process, the x-rays were then cut into seven-inch discs and grooved at 78 RPM. The center spindle was made using the end of a lit cigarette. Tomar cites Russian rock journalist Artemy Troitsky who explained that “record printers upcycled [sic] old phonograph machines to create their own crudely constructed record lathes.” Much less expensive than the cost of an legitimate LP smuggled into U.S.S.R., which could fetch five rubles, an x-ray record might cost as little as a single ruble. The sound quality of a bones record was, needless to say, abysmal, and the whole experience maddeningly ephemeral: a buyer was lucky to get maybe ten spins out of an x-ray record before it was rendered permanently unplayable.

Imagine: songs you love and have coveted, finally arriving via risky channels and shady machinations, etched on a perishable image made of wavelengths and radiation, a picture of the inside of something rotating wobbly as your own insides are altered by the music. And after a few more spins, it’s all gone—it might take a precious week, it might a single night.

“The activity of bones bootlegging was officially added to a list of restricted ‘hooligan trends’” in the Soviet Union, “a catch-all term for the untoward behavior of the Soviet youth subculture—referred to as stilyagi. Such behavior generally included an embrace of Western style, dance, and music,” Tomar writes, adding, “This is what makes the story of ribs recordings an important one. By the early ‘60s, people living under Soviet rule faced genuine peril just to hear the Beatles and Stones.” (For a deeper look at ribs records and the historical work done by Stephen Coates of British indie pop band the Real Tuesday Weld at his X-Ray Audio initiative, check out this terrific article in The Guardian.)

Related post:

A boy like me

It’s unclear in what year Dibrova sets his brief story, but the its mood of Cold War paranoia is palpable. The sabotaged rail transit, the heavy-handed Militsiya interrogation, the illicit x-ray recordings, the freedoms promised in a bootlegged rock and roll song—each evokes Iron Curtain totalitarianism and gray dreariness. As I read Dibrova’s story I was swept up in the kids’ urges, and though the title gave the game away, when Paul McCartney’s grinning count-in arrives at the end of the tale I’m right there in the room, watching a ghostly rib cage or a skull spin on some shitty up-cycled turntable as “the Beetles” sing their hearts out about teenage lust and the liberation of dancing, everything exciting beyond words, everything as elemental as bone, everything fated to vanish for good, like a precious dream. Positive vibrations filling the room and spilling beyond borders.

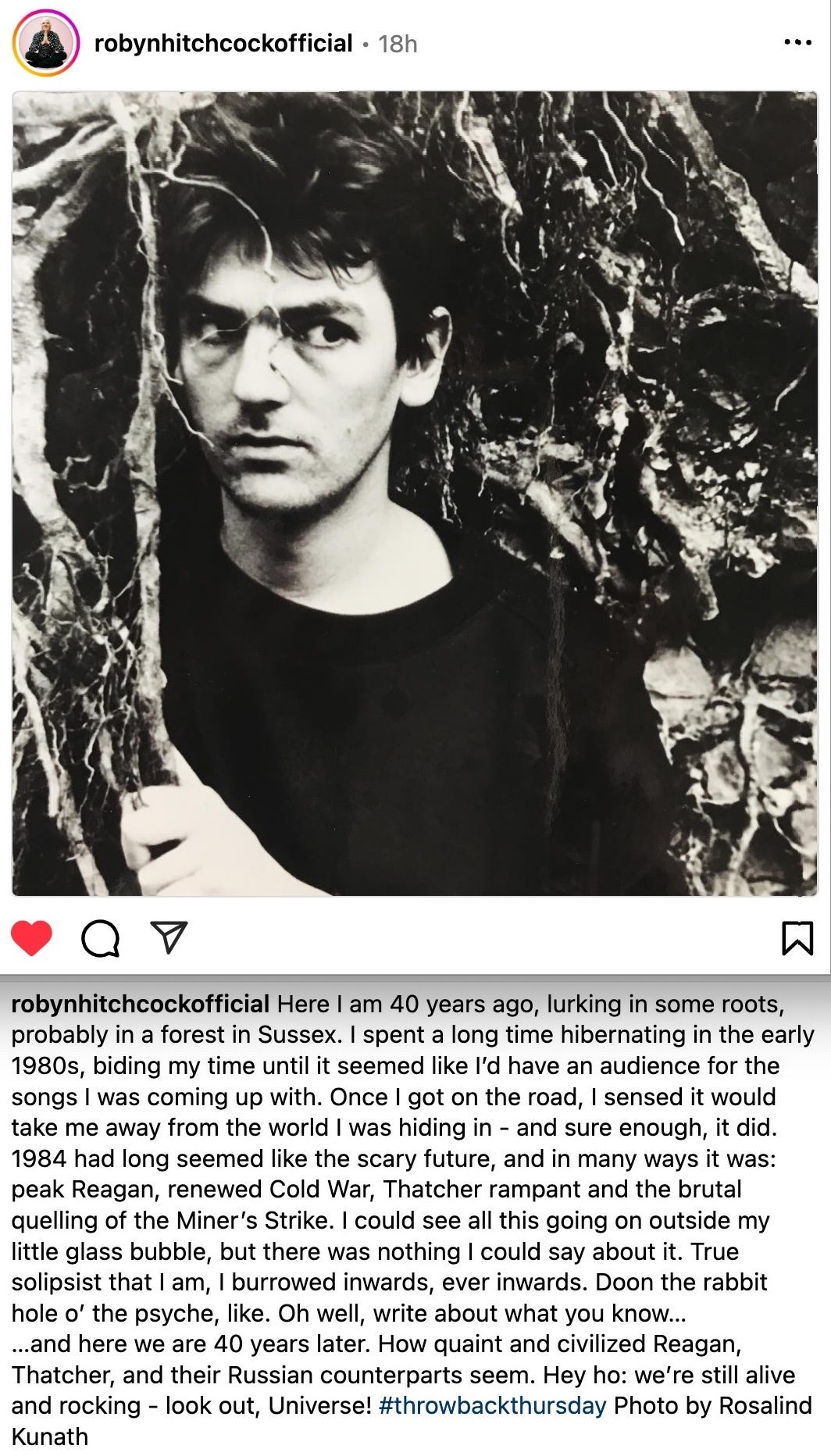

In a recent Instagram post, Hitchcock shared a forty year-old photograph of himself peering warily out from some woodland scene, “probably a forrest in Sussex.” He writes that the mid-1980s “had long seemed like the scary future, and in many ways it was: peak Reagan, renewed Cold War, Thatcher rampant and the brutal quelling of the Miner’s Strike.” He adds, “How quaint and civilized Reagan, Thatcher, and their Russian counterparts seem. Hey ho: we’re still alive and rocking—look out, Universe!”

See also:

Image of “Bone Records, X-Ray Audio,Ribs” by Marcus O. Bst via Flickr