The Ramones were a mighty paradox: coherence on the outside, dysfunction on the inside. Their touring van was a graphic metaphor: moving forward professionally and dependably as the passengers inside moved testily in their own worlds. Assigned seating; assigned chit-chat; assigned roles.

By the end of the long road in the mid 1990s, the band members were barely tolerating each other, fuming between gigs, likely even between songs onstage, mad-dashing through hyper-accelerated sets in order to get off as swiftly as possible, to get Joey back into his routines and Johnny to his. Outwardly the band rarely exposed the fraying seams, the odd interview revealing light squabbling about band direction or bemused reactions to each other’s personalities. Their devoted fans were for the most part in the dark about the band’s dysfunction until the tell-all books started arriving, first from Dee Dee, and then the others.

In retrospect, listening to Ramones albums in the Eighties was like assembling a mosaic: the murkiness of Phil Spector’s End of the Century (1980), the mild pop leanings of Pleasant Dreams (1981, redressed somewhat in this year’s Record Store Day release of the so-called “New York Mixes”), the now-dated gloss of Animal Boy (1986), the swiftly diminishing returns of Halfway to Sanity (1987) and Brain Drain (1989) produced an image of a band pulling unhappily in many directions at once. Too Tough to Die (1984) sounded fantastic, but the sonic divide between Johnny/Dee Dee and Joey began widening, and too few songs stuck. Each album has a handful of terrific tracks, but by the end of the decade the Ramones sounded uninspired, and tired. And: 2,263 gigs is a lot of gigs.

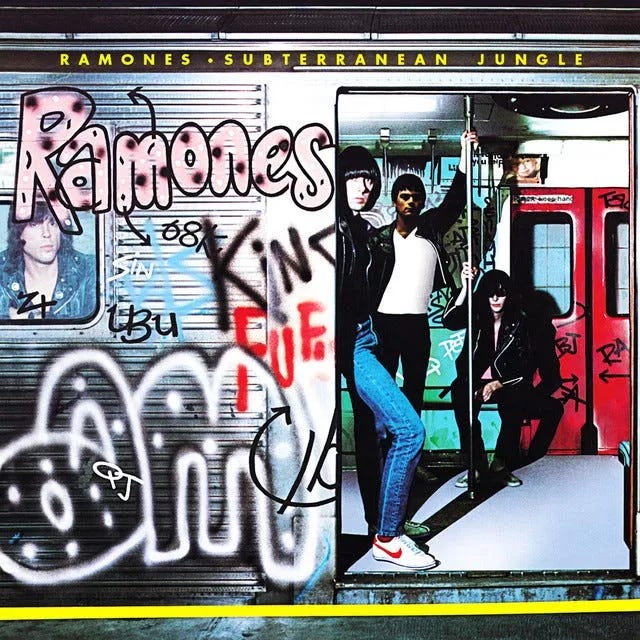

Subterranean Jungle, released in February 1983, is to my ears the last great Ramones album, where the band members’ tastes and desires were cohering rather than dispersing. Produced by Ritchie Cordell (Tommy James and the Shondells, Joan Jett, et al) and Glen Kolotkin, Subterranean Jungle, like so many Ramones albums, has polarized fans. Some, including drummer Marky Ramone, deplore the of-the-era sound. Marky wrote in his memoir Punk Rock Blitzkrieg that Cordell “had his own way of tuning, which made each drumhead sound as if it had a towel over it,” adding, “There was no bite, no hit. No Balls.” Some, including the guitarist, have complained about the presence of three cover songs on the album (they actually recorded four, 1910 Fruitgum Company’s “Indian Giver” failing to make the cut) or the inappropriately heavy guitar sound, others about Johnny sporting the “wrong” Ramones Sneakers on the album cover. (At least they were wearing their leather jackets.)

Characteristically, the band bickered during the recording sessions, both internally and with their newly hired producers, toward whom they were aggressively skeptical given the poor charting performance of their two previous albums. (Tommy Ramone has remarked that the band had wanted him back in the fold as producer around this time, but that their label was insisting on commercially-successful outsiders. He’d return to produce the next album.) The interpersonal strains were there, and always would be, yet Johnny remarked to the band’s tour manager Monte Melnick in On The Road with The Ramones that during the ‘82 recordings he felt as if the band was “starting to get back on track,” that at he and Dee Dee “were at least talking at that point.” In Everett True’s Hey Ho Let's Go: The Story of the Ramones Dee Dee recalls that in this period he “decided [he] wanted to be friends” with Johnny again, and resolved to revive their writing relationship.

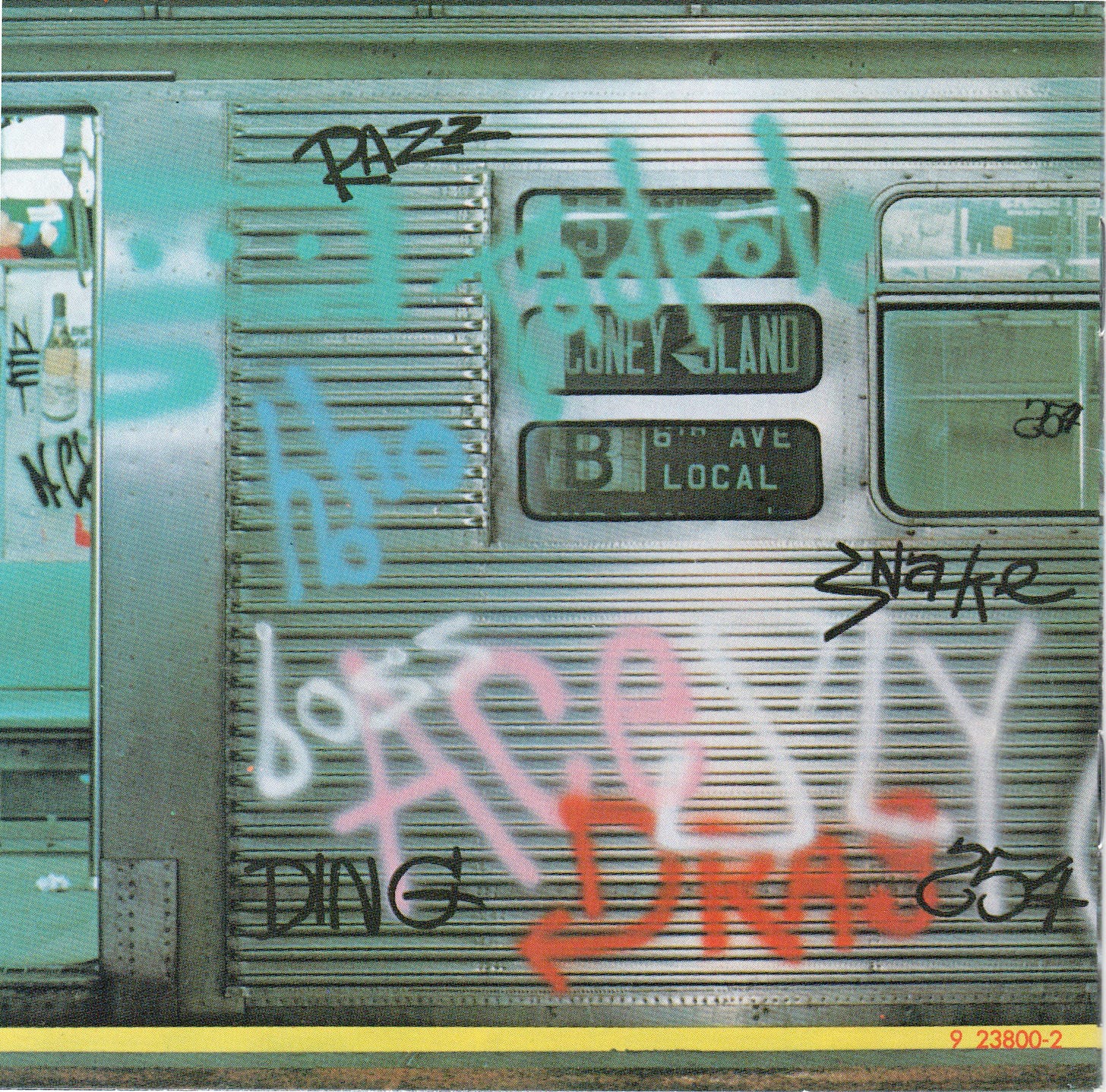

Marky’s alcohol abuse crested during the end of the sessions, his unreliability and mood swings a real issue, and as has been reported in many a Ramones chronicle, both Johnny and Dee Dee wanted him out. (In the event, Billy Rogers played drums on one track, “Time Has Come Today.”) The album cover is an infamous in-joke wink: George DuBose photographed the fellas in a subway car at Fifty-seventh Street and Sixth Avenue station, where the B Sixth Avenue Express train would idle for twenty or so minutes. It’s been variously reported that Johnny—or Johnny with Dee Dee, or Melnick, or DuBose himself, all directors extraordinaire—suggested that Marky be positioned alone at a window seat as the rest of the band members posed, together, only a few feet away.

See ya later down the line. Marky was kicked out of the band before the album was released. (Outtakes from the session show Dee Dee sitting apart from the band in one photo; he left the group in 1989.) “It was hard to tell if George suggested it or if I did it instinctively, but either way it seemed like a good idea when I scooted over to a window seat,” Marky wrote of the awkward tableau, adding wryly. “I looked out the window like a lonely commuter. George took half a roll with us like that, each click recording a slightly different nuance of the same somber mood.”

One of the first things a visitor, tourist, or transplant to New York learned was that the subway wasn’t for having conversations with strangers and making new friends. You barely even talked to your old friends. And so the shoot for us came naturally.

All I know is that when I crank up Subterranean Jungle I hear a dozen songs that sound as if they’re being launched from a single bunker. Producers Cordell and Kolotkin, aided by engineer Ron Cote, who’d also worked with Joan Jett, thicken Johnny’s barb-wire sharp guitar with volume and layering, and a touch of distortion, and mix it so high so that you can virtually feel guitar strings and see the room’s amps as you listen, less an in-your-face mix than in-your-hands. Squeaks on the fretboard and a bit of feedback add to the excitement and immediacy, to the recorded noise so tactile that—careful—if you run your fingers over the vinyl you might get cut. Johnny himself, a hard man to pry compliments from, loved the album’s guitar sound.

The band also invited Walter Lure, from the Heartbreakers, to add lead guitar to the tracks before mixing began. I can hear him especially on “What’d Ya Do?”, “Somebody Like Me,” and the unfortunately named “Everytime I Eat Vegetables It Makes Me Think of You,” as his solos—Johnny never bothered with ‘em—rip and tear in vintage Bowery street-rock style, giving the impression of what the Ramones would’ve sounded like onstage with a guest (a gesture they finally gave in to at their last performance in 1996). Subterranean Jungle is a really loud album that sounds best played really loud, the guitars’ sonic waves of churning sound buoying a raft of desperate, unruly songs.

None of which would matter if the songs weren’t strong. The material that Dee Dee and Joey were (mostly singly) writing in the summer and fall of 1982 certainly works well-tread paths—the Ramones template was more or less in place by the end of the first side of Leave Home (1977)—yet inspiringly so. Joey’s “My-My Kind of a Girl” is a vintage Ramones ballad, the pretty melody and yearning lyrics muscled into bravado by those loud, slashing guitars, which could easily bully the singer into shyness but instead act as his wing-men, grinning in support as he serenades his latest East Village jukebox crush (“And this time I think it is forever”). But Joey’s “What’d Ya Do?” revisits the couple a little while later: “I thought we’d last forever,” the singer reminds her. But she had other plans. His surprised hurt is masked by indignation, reflected in the song’s angrily aggressive opening bars and the strutting chords in the chorus, as he bids her and a fated downtown romance farewell.

I’ve written before about the emotional power in Dee Dee’s best songs. For Subterranean Jungle Dee Dee produced a clutch of hard-edged tunes, a few of which are among his best from the era, one of which is an all-timer. In “Outsider” he offers a familiar persona, a pushed-around, put-down misfit who can’t, or won’t, fit in and feels as if he’s fated to look at things from the outside in. The die is cast—

All messed up, hey everyone

I’ve already had all my fun

More troubles are gonna come

I’ve already had all my fun

—so all that’s left is to play out the string. (Tellingly, Dee Dee takes over from Joey to sing this bridge.) Yet on “Somebody Like Me” and “In the Park” Dee Dee offers cheery hopefulness of a sort, two songs that celebrate individuality and community. The singer in “In The Park”’s heading out “to be with the gang tonight” beneath a “big, bright moon” that “shines a friendly hello.” There he’ll mess around “under street lamps” as “kids in cars go cruisin’ by” as “music's playing that portable sound / While everybody's hanging all around.” Notably absent in this singalong is any reference to hard drugs.

The requisite tube of Ramones glue™ does pop up in “Somebody Like Me,” though its use here suggests less a fucked-up tumble into oblivion than a vulnerable step toward identifying with like-spirits. The singer’s tired of bitching and is ready for fun, vowing tonight to make friends with anyone: “Are you out there somebody like me? / If you are, I hope that you can see.” The song’s chorus is classic Dee Dee Ramone, a clarion call, or a shoulder-shrug. It’s also a manifesto:

I’m just a guy who likes to rock and roll

I’m just a guy who likes to get drunk

I’m just a guy who likes to dress punk

Get my kicks and live up my life

My older brother Phil worked briefly as a hired driver in college. Years ago he told me that he once dropped off a rich-smelling suit at the airport, and just as my brother drove off, heading home after a long shift, the Ramones’ “Psycho Therapy” came on the radio, the opening riff heralding the end of a shitty work day and the thrilling promise that something dangerous and fun is charging. An appropriate scene in the movie that a great rock and roll song can write. Written by Dee Dee with Johnny, “Psycho Therapy” is an intense, gripping song, the opening and closing siren-wailing hair-raisingly evocative. The song comes fanged with one of the Ramones’ greatest riffs, and Joey sings around and through it with gusto.

If the lyrics parade stock Dee Dee imagery—the “psycho zone” juvee on downers who brags that “pranks and muggings are fun”—the band’s excitable playing, especially Johnny’s buzzsaw riffing and rousing changes, cut and tear at those lyrics until what’s left feels genuinely frightening, and frightened. “Psycho Therapy” is one of the Ramones’ great songs of the 80s, which also means that it’s one of the great rock and roll songs of that decade, Reagan’s America:

The albums’s three cover songs suggest that the band might’ve been low on original material, yet the expanded edition released in 2002 contains a previously-unreleased original (“New Girl in Town”) and several decent demos of songs, one or two of which could’ve presumably have been worked up for the album.

Yet I’m grateful that the Ramones dug into their bag of favorites to record tunes that celebrate the band’s roots and make the party only more boisterously fun. The album’s opener, “Little Bit O’ Soul,” a gargantuan hit for the Music Explosion in 1967, is an irresistible party invitation, the immensely loud, pawing guitars pushing you through a door you’re not sure you’re ready to enter, but the riff’s already put a smile on your face, so what the hell. I’ve written recently about the Boyfriends’ “I Need Your Love,” which Joey sings here with the kind of commitment that makes the ecstatic, desperate song sound like his own. I thought it was a Ramones original when I first listened to the album, until I read the notes.

The album’s third cover, of the Chamber Brothers’ 1967 psychedelic stomper “Time Has Come Today,” is monstrous, a phasing-, reverb-drenched recording that, slow-tempoed for a Ramones rocker, gains momentum via one rawly exciting passage after another. Joey has fun with his phrasing of the “psychedelicized” lyrics, the guitars are enormous, and the backing gang-singers are full-throated in a rousing performance of a damn righteous song. Well chosen, and well sequenced too, following as it does the eighth-note blur that is “Psycho Therapy,” providing a welcome, trippy come down that’s no less riveting.

The Ramones’ image, forwarded by their jeans-and-leather uniforms and Arturo Vega and John Holmstrom’s deviantly-zany comic-strip graphics, has always been cartoonish, yet I’ve always taken their lyrics seriously, especially after reading accounts of the various personal anguishes, disorders, and addictions suffered by Dee Dee and Joey, the band’s main songwriters. When these guys sang about being, or anyway feeling like, misfits, social outcasts, and dopes, they meant it. They weren’t always trying to be funny.

The “bubblegum punk” that Cordell and Kolotkin brought to Subterranean Jungle unifies the songs sonically yet doesn’t remove their teeth. What Marky’s drum sound may lack in force, Johnny’s (and Walter Lure’s) guitars more than make up for in sheer volume and physical presence, balancing the soundstage nicely, if perversely. Joey’s in top form, the band’s characteristically tight, the songs are nearly all top-shelf—everything’s in service of a united sound. As terrific a rock and roll record as the follow-up album Too Tough To Die is, two tracks, “Chasing the Night” and “Howling at the Moon (Sha-La-La),” with their bright keyboards and synths, and undue length (each a minute and a half longer than any other track on a lean, back-to-basics album), feel imported from another, less interesting, more commercially-minded record, a schizophrenia that plagued far too many Ramones albums.

“It’s to do with the age you first heard the Ramones.” That’s Slim Moon, founder of the Kill Rock Stars label, quoted in Hey Ho Let's Go on how an album can get inside you and stay there.

[Subterranean Jungle] is my favorite album. “Psycho Therapy” is great. I remember the clerk who sold it to me was just appalled. “This isn’t a real Ramones record.” I like the classic first two records, too. I’m not a purist about it.

I was looking the other way when Pleasant Dreams was released, and though I was aware of the band’s first few albums (thanks to my older brother and the DJ’s at WHFS, the local progressive music station in Bethesda, Maryland) the band wasn’t yet on my radar. I’m fairly certain that I bought Subterranean Jungle shortly after it was released in early 1983, my first Ramones album, and I saw the band for the first of many times a year later. Though they would righteously deliver onstage for many years, they never released an album as consistently great as Subterranean Jungle.

See also:

Me, Mom, and Daddy, sittin' here in Queens

You don't know what it's like

When it's right

The Ramones via Max's Kansas City (no changes)

I discovered this album way late. It's my favorite 80s era Ramones album for sure. "Somebody Like Me" is my favorite track even though it's totally riffing on a slow tempo "Blitzkreig Bop" haha. It's like come on man.

“Ah hope yuh parenth unduh-THTAAAAND”