Tripping with Ellen

Ellen Sander's evocative descriptions of rock and roll in the process of becoming Rock

In June 1967 the music writer Paul Williams broke a story that never happened. “It looks very much as though Michelangelo Antonioni will direct the Beatles’ third film, Shades of a Personality, shooting for which is scheduled to begin in Malaga, Spain, in September,” he reported, in a column later gathered in his first book Outlaw Blues: A Book of Rock Music. “The story line involves the four faces of a man (himself as dreamer, as seen by the world, as member of mankind, as seen by himself), each played by a different Beatle. Meanwhile, the Beatles are trying to complete filming of a TV spectacular, and a new album, by early fall. Mmmm, such a flurry of activity!”

The “TV spectacular” materialized, of course, as the ill-fated Magical Mystery Tour, broadcast in the U.K. on Boxing Day that year, yet the rumored meeting of John, Paul, George, Ringo, and Michelangelo was, sadly, never to be. Antonioni was hot off of his first English-language film, the swingin’ Blow-Up released in 1966, but, as Mike Tyrkus writes at Cinemanerdz, scheduling conflicts and concerns within the Beatles’ circle about the quality and suitability of the script torpedoed the project, if it was ever a project at all. The attachment of the hot Antonioni to a hot Beatles Film Project was in all likelihood a fanciful wish leaked by someone to the press, or was imagined out of whole cloth, a rumor that sparked a briefly-lived fire.

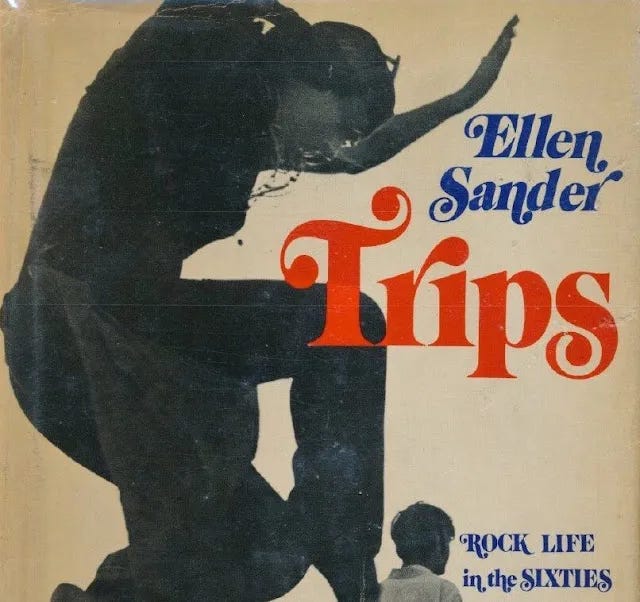

Such “what ifs” are endlessly fun to think about. Equally fun to read is on-the-ground reporting in that era that got things right. (No shade at Williams, of course; he was simply reporting, wishfully, what he heard.) Ellen Sander is a reporter-turned-poet who in 1973 published Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties, a book of music writing. I hadn’t read it until recently, though I certainly knew Sander’s name well, as music writers I admire have often cited her. I devoured my university library’s copy of the original edition, which was lamentably absent a chapter on Cynthia Dorothy Albritton and her fun-loving maverick pals in Plaster Caster which Dover rightfully added when they reissued the book in 2019 (pictured above). “Scribner wouldn’t print [the Plaster Caster piece] at the time even though it was the story that broke the groupie scene open,” Sander told Lela Nargi at Publishers Weekly. (The piece was published originally in the Realist.)

Writing for high-circulation magazines such as Life, Vogue, Saturday Review and smaller publications as well, Sander was an informed, turned-on, clear-eyed reporter of the late-1960s music scene, her writing both objective and deeply personal, a blend that’s catnip to me. I heartily recommend the book if you’re interested in on-the-ground descriptions of rock and roll as it was in the process of becoming Rock, its mythology exploding as folk musicians and second-wave pop artists (Beatles, Dylan, Stones, Byrds, et al) were in the throes of both rolling back the limits of pop music and questioning their songs’, and their own, cultural value. Sander didn’t change much in the reissue “because I wanted to keep that voice, even though some of the writing is cringe-worthy. Some things I couldn’t abide, like calling Jimi Hendrix a ‘spade.’ It was the parlance of the time, but I couldn’t live with it now.” She added, “Sometimes the language was too casual in terms of first or last names that I would throw around; I put whole names in because people are not too familiar with them two generations later.”

In the original preface to Trips Sander admits to some disbelief that the book ever came into being. “I was merely the collector of anecdotes, the detective of revealing details, the nibbler concocting a fest of my favorite adventures, and everyone’s pet road story,” she acknowledges appealingly. Goaded by her pal David Crosby into collecting the pieces into a book, she soon recognized that her journalistic work told a wider story. “The result is not meant to be a reference work, comprehensive in its scope, or a rigidly detailed history,” she writes. “It is a story of a time, parenthesized by ambivalence and apathy, yet bursting with energy, humor, adventure, a search for the ultimate high, a generation with an irrepressible vision, its art and artists and its audience, the substance of its statement.” Most importantly, she adds, “it was written in the period it describes, though published shortly after. What I have given to it—and received from it—is a sampling of the esprit of the rock and roll Sixties, a smattering of the personalities, and impressions of the impact as events were happening.”

A bit later she writes:

To all the makers of myths and music and the wonderful madcap scenes surrounding them, the dazzling highs and the inevitable come-downs and the things learned in between, what follows is a love letter to you and the times we lived together. There was a significant change in awareness during these times, and we are all of us more sensitive to one another today.

The observations Sander makes about being a teenager in the terrific piece “Teenism in the Fifties,” though era-specific, are eternal in their mix of frustrations, awe, and righteousness. “One day, in ‘hygiene’ class, the girls were shown a film on menstruation," she writes, remembering her gray years as a high school student in the Eisenhower era. “The same day, in ‘shop,’ the boys saw a film on V.D. The next day we all saw a film of Hiroshima together. I learned to menstruate and live in terror of the Bomb the same week.”

The mushroom cloud flared, it rose and crested in magnificent bursts of fire and power. It was one of the most movingly beautiful sights any one of us had ever seen. Our minds broke in terror and awe. We walked out of the auditorium changed children. Our pants were hot and we were full of paranoia. The cycle of anger, fear, and rebellion had started. We’d had our illusions busted and it was only the beginning.

Later in the essay she remarks, “It struck some of us that it was their world and we didn’t care much about admittance to it. There had to be a better way and we had to find it. We looked in other directions.” The only thing “specifically and exclusively” available for Sander and her friends? Rock and roll.

The music grew louder, raunchier; dancing grew crazier and our bodies and minds convulsed in a rapturous motion that was both an escape from, and a direct response to, the precarious spasms of events.

Sander’s was a generation “cut off from the past by total absorption with the present.” She added, “And our parents thought surely that it was a phase, that we would outgrow it.” Yet how can you outgrow your own that which gives you your body back to you? Total absorption with the present is as moving and apt a naming of the gifts that music gives that I’d read in some time. I experienced that penetration into a moment just last night listening to Robyn Hitchcock’s delightful 1967: Vacations in the Past, his autobiographical musical immersion into his teen years where timeless songs meet the present, deep desire to revisit them. I experience it at shows, and in the car when a song surprises me on random play; clutching the wheel against bliss or despair, I enact that “escape from and direct response to” dynamic that Sander writes about so well.

Sander wasn’t afraid to write about her own fandom or about her drug use, nor the loutish behavior of some of the bands that she covered and admired. Her “ambivalence and apathy” seemed grounded in raw moments of unwelcome insight. At the shuddering close of “Can I Borrow Your Razor in Minneapolis,” her account written for Life magazine of traveling with Led Zeppelin for a week and a half on their 1969 U.S. tour, she’s assaulted by “two members of the group” who ripped down the back of her dress, one of the most graphically disturbing things I’ve read about Rock entitlement and misogyny. (The dress stayed on, thankfully.) Sander had grown close to the band in the mutually respectful, professional way that a traveling reporter can, the assault all the more confounding and heartbreaking, if grimly unsurprising, because of that.

The story deserved to be printed at the time, yet its initial reporting was, unsurprisingly, stripped of telling details. In an interview with Gary James at Classic Bands promoting the reissue of Trips, Sander recalls an interview she gave for Rolling Stone on the occasion of the book’s initial publication in 1969 in which she reported that Led Zeppelin’s drummer John Bonham had physically menaced her, only to be restrained by the band’s manager, Peter Grant.” A half century later she remarked to James, “Obviously I am not going to speculate on what might have happened because what’s the point? It does not seem productive to speculate on that.” The reprinting of Trips afforded Sander the opportunity to write more fully and graphically about the cruelties she witnessed and experienced on that tour. “The reason [Rolling Stone] did not want to mention one of the assailants (in addition to John Bonham) was because they anticipated there might be some legal jeopardy.”

She added dryly, “Led Zeppelin had a reputation for rather riotous encounters while they were on the road, sometimes involving the humiliation of women.”

The closing sentence of “Can I Borrow Your Razor in Minneapolis” is striking: “If you walk inside the cages of the zoo you get to see the animals close up, stroke the captive pelts, and mingle with the energy behind the mystique You also get to smell the shit firsthand.” In under forty words Sander captures both the allure and the darkness of a slice of rock stardom as experienced by many females—I doubt I'll ever forget the passage, which crosses an enormous terrain and returns to describe it, and to name it, succinctly and powerfully. That I can hop online and read accounts, from last year, last week, of similarly louche behavior by musicians today only underscores how entrenched misogyny and cruelty still is. Sander’s clear-eyed takes on the joys and the darkness of music were tonics at the time, and are still bracing in their candor and nerve six decades later. Take a trip with her if you can.

See also:

Richard Goldstein on The Scene

“Hiroshima after the Bomb” by Wasfi Akab via Flickr

I've read a lot of similar '60s rock tales, but this book sounds interesting. I will keep my eye out for it.

I acknowledge the huge impact Zeppelin had on rock music, and I like their music. However, the more we read tales such as these—the misogyny, sexual assault, Page's interest in young girls, ripping off/not crediting black artists (and Randy California/Spirit!), the more I dislike them as human beings, which gets in the way of being able to appreciate their music. They are one of the ones I struggle to separate the art from the artist. It's shameful so much was censored and how complicit the entire industry was. Of course, LZ was certainly not alone (and it wasn't just girls who were abused). The horrific story of The Bay City Rollers is one of the absolute worst I have heard, and nobody stopped it nor came to protect the boys. I'm sure the entire '80s metal scene of boys behaving badly, no doubt, has equally horrible, toxic tales.

You've sold me on reading this book as I'm going to be focusing on women in rock this year (artists, groupies, others). Very interested in the perpective of a woman journalist during that time. So thanks for profiling this book.