Only time can write a song

Some thoughts on Richard Hell and the Voidoids' underrated Destiny Street

“1974 is a lot different than 1970.”

So remarked Pat Thomas in a conversation with Doug Yule reprinted in the latest issue of Maggot Brain. Thomas was referring to when Yule, who’d replaced John Cale in Velvet Underground, reunited with Lou Reed in ‘74 for Reed’s Sally Can’t Dance album and subsequent tour. “I hadn’t really followed Lou’s career [at that time],” Yule remarked, adding dryly, “But I know the year before I was with him, he was in his blonde Nazi phase.”

I read this exchange as I’m revisiting Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ second album Destiny Street. The album was released in 1982, which is a lot different than 1977. Television had been broken up for several years. Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers had recently splintered. Patti Smith was on the verge of (semi) retirement. The Ramones had recorded in Los Angeles with Phil Spector. Meanwhile, Talking Heads were on their way to mass mainstream success while Blondie had already gotten there. Five years after the release of Hell and the Voidoids’ landmark debut album Blank Generation, Richard Hell, though keeping busy writing and appearing in the odd film (Blank Generation, Smithereens), was spiraling, addicted to cocaine and in and out of fractious relationships.

In 1981 Hell reconvened in the studio with Robert Quine, the only other original member of the Voidoids, to rehearse and record new material. Hell wrote in his 2013 autobiography I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, “When I asked Quine to join me, he committed immediately and I took his suggestions for drummer and second guitar, respectively Fred Maher and Naux (pronounced Naw-OOSH—originally Juan Maciel),” adding, “I didn’t consider Ivan from the original Voidoids because I wanted to hear a new guitar combination.” During rehearsals, Hell would regularly smuggle in his syringe and his stash, vanishing to the bathroom every twenty minutes. “I thought the band would accept my explanation that I’d been drinking too much coffee” he wrote. “One afternoon when Bob used the bathroom immediately after me he returned scowling and seething, but still it didn’t hit me for another couple of hours that he had to have seen my blood spattered across the porcelain.”

Such fraught circumstances resulted in uneasy rehearsals, work made all the more difficult by the guilt hanging over Hell due to his poor preparation of his own material. “I had three or four of the songs only half-arranged,” he admitted. “I’d left the proportions of parts to parts (verse, intro, chorus, outro, etc.) undeveloped, and I had no final bass part ready for two or three others. And this was out of a total of seven original songs.” He added, “I’d also intended to show off my development as a composer by including bridge parts (that single-verse break, like a tune within the tune, that livens up most great songs), but I never got around to it.”

During the three weeks of recording and mixing Hell couldn’t fully commit, and missed one full week of work. “I was strung so tightly by cocaine into supersensitivity and paranoia that I couldn’t tolerate the thought of stepping outside,” he acknowledged. “If I’d gone into the street, some passing stranger might have unexpectedly coughed in my vicinity and blown me out of my skin. I’d call the studio and try to act as if it was an aesthetic choice to instruct Bob and Naux to add some more guitar in this place or that.” He added, “As a result, by the time I could summon the strength to return, the record was a piercing, percolating drone of trebly guitar noise.”

“Despite all this, I did then and do now consider the material on Destiny Street to be superior to the set on Blank Generation.” Though I can’t fully agree with Hell here, I do feel that Destiny Street is a terrific and vastly underrated rock and roll album. It’s a worthy, wounded successor to the nerve and urgency of his storied debut, a necessary document of dissolution and desperation in its own right. Though Quine, Maher, and Naux didn’t set out to recreate the original Voidoids’ signature noise, they nonetheless echo it in their taut, excitable playing behind Hell’s characteristic yowling. “I’d learned a lot about making songs since 1977,” Hell reflected, and so “[t]he songs on Destiny Street had an internal consistency to them, a more satisfying feeling of inevitability. On the other hand, the songs weren’t as unusual in either their style or subjects as the songs on Blank Generation, and their arrangements were sloppier. But strictly as a collection of songs, as opposed to performances, Destiny Street is the better album.”

Yet Hell has long held reservations about the record, no doubt informed by his crippling addictions in the era and the unhappy circumstances of its recording and mixing. In 2009 he was able to revisit the tracks via a 1981 reference-cassette that contained the original live-in-the-studio rhythm tracks; on top of these he laid new guitar solos from original Voidoid Ivan Julian and Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell. (Hell stresses that Quine would have played on the tracks had he been alive.) A decade later, the 24-track masters were unearthed and, as Hell remarked to Jean Marc Ah-Sen in Hazlitt, he finally “was able to carry out my fantasy of remixing the original.” The whole sprawling, two and a half hour thing, the ‘21 remix and ‘09 tracking plus a clutch of demos recorded between ‘77 and ‘81, is available to stream as Destiny Street Complete.

“People say, ‘But I liked the first one!’ It’s almost inevitable that if you’re familiar with a version of a song you like, another similar version will sound wrong,” Hell said a few years ago to Chris Cotonou at Insidehook. “For me, the original album is still difficult to listen to. When I got the rights back 15 or 20 years ago, I deliberately let it go out of print and refused to license it again.” He added, “There’s absolutely nothing to prefer about the 1982 version except that it’s part of a story, the story of Destiny Street Complete. But the clarity and power of the remix is clearly preferable.”

In the midst of describing Destiny Street’s sonic journey to Ah-Sen, Hell said something really interesting: the execution of songs, in his view, “is more interesting than the content. Take the way blues songs can be so similar to each other—it’s how they’re performed that matters. I had the fantasy after we released Blank Generation in 1977 that I’d never make an album of other songs, but just re-record that one differently every eighteen months.” Fascinating idea, that every year and a half or so we’d get a new Blank Generation. What would “Love Comes In Spurts,” “Down At The Rock and Roll Club,” or the epochal title track, re-inhabited, have sounded like in 1982, 1985, 1992? Anthems for the generations spanning Carter to Clinton!

Anyway, the opening song on Destiny Street, “The Kid With the Replaceable Head,” feels like a hyperactive sequel of sorts to “Blank Generation.” If it’s a gamble when you get a face—“The doctor grabbed my throat and yelled, ‘God’s consolation prize!’”—well, five years later you’ve got some options lining your bedroom wall:

He used to beat himself up ‘til he was sick and confused

Dead tired and throbbing, half crazy and bruised

’Til he’d be too worn out to keep being himself

Now he can pick ‘em at will from the heads on his shelf

He’s a mental invention, the singer’s “three best friends” wearing a head for every occasion. Above the thrashing, Hell sneers and yelps, the nasally sarcasm ™ in his voice pitched somewhere between irony and affection for the titular kid, who’s so honest in his multiple personae that the dishonest avoid him out on the street. The po-go-ing chorus is vintage Voidoids—excitable, nervous, and angular.

Destiny Street is not a flawless record. I enjoy the original mix on vinyl just fine—the sound’s bright and punchy—but the songs are uneven. “Ignore that Door,” “Going Going Gone,” and “Staring in her Eyes” are less songs than ideas, Hell’s band creating a racket or a slow burn behind him in order to find the sonic space that the songs deny them. The band covers the Kinks’ “I Gotta Move” and Them’s “I Can Only Give You Everything,” choices originating in Hell’s desire to get back to basics, “to make an album of the kind of music that originally inspired me,” he said to Ah-Sen. He also cited “the sneer and the drive” of Bob Dylan’s first electric albums as “the inspiration for half of my songs on [Destiny Street], and it was only natural to include some related covers too [and] the kind of repertoire of the ‘60s party bands.” He added, drolly, “This is how I think of it, though I can’t swear how conscious it was at the time.” “I Gotta Move” rides its killer riff commandingly, and the band’s clearly getting off playing in and around it, but “I Can Only Give You Everything” goes off the rails at the end, where Hell howls and bleeds but the effect feels to my ears somewhat performative, or, worse, on some listens, generic. (“By the time I got to the end I was in tears,” Hell revealed in his autobiography. OK, I’ll defer to his version of events.)

The brittle downtown funk of the title track closes the album with a pretty irresistible conceit, as one day the singer steps off of the curb and runs into a version of himself from ten years ago: “I scared myself, I was horrified / But elated, too / Like I’d escaped from ten year’s shell / I'd never known was fulla Hell.” (Today, anyway, the pun works for me.) He remembers with start that he’d also experienced this a decade earlier, and so three versions of Hell seduce one another and head back upstairs to reckon with the sobering reality of years settling like transparencies: “We were playing house / Pretending we could hide inside the past and future / To avoid our present self.” Bemused yet affected, Hell struts and talk-sings the modest shaggy dog story, street poetry where nothing in the music nor in the tale resolves, which feels like life to me: more questions than answers.

Especially powerful is “Lowest Common Dominator,” a charging, rocking kiss off to an asshat who gets off on overpowering others. The knotty rhythms, nutty pace, and punning, singalong chorus give early-80s New Wave, but the sparks in Quine’s solos fire straight outta the street rock gutter, wrenching, wounded salvos that threaten the bully more graphically than the lyrics. Though Hell does dig in the knife: “Oh, we'll just leave you knowin’ / Your worm insides are showin' / And that's a revenge enough.”

The best songs on Destiny Street are the two that bridge the album’s sides, “Downtown at Dawn” which closes side one, and “Time” which wisely if wearily opens side two. The first feels like two songs in one, really, a glittery dance floor jam spun into ecstatic blurs by Quine’s glittery solos—his finest playing on the record—and Hell’s morality tale about the drunken ghouls and fools who are seduced by the glamour and the music, forgetting who they are. The imagery’s brutal—we’re all a whore, and now you stand inside the door; downtown at dawn, where we rub to the nub; and coalesce, remove your dress, and think about it less and less—and setting an emptying nightclub and its hopeless, ashen-faced customers against an indifferent rising sun only bruises things more.

Hell’s at his best as a songwriter when he turns his autobiographical persona into a silhouette into which anyone can fit. In the mid-paced, knowing “Time” Hell’s ostensibly singing about songwriting, yet he’s found a voice for anyone who struggles to move from feelings to language—that is, every one of us. He wants to “write a song that says it all at once” but if he tries he know that he’s “gonna take a fall at once.” What’s left? The sobering discovery he makes in the chorus, one of the most affecting passages in any of Hell’s songs—

Only time can write a song that’s really, really real

The most a man can do is say the way its playing feels

And know he only knows as much as time to him reveals

—that, it turns out, prepares us for the insights that Hell, moved, sings in the song’s final verse—

We are made of it, and if we give submission

Among our chances there’s a chance we can choose

And if we take it by uncertainty’s permission, then

Then it’s impossible to lose

I bet that he was surprised at where this song took him, and grateful for it, too. His singing sure says so. Did the epiphany take? Well, Hell stopped making music soon after Destiny Street was released. Your guess is as good as mine.

Sell also:

Slipping in and out of phase

Big deal, baby, I still feel like hell

Walter Lure survives

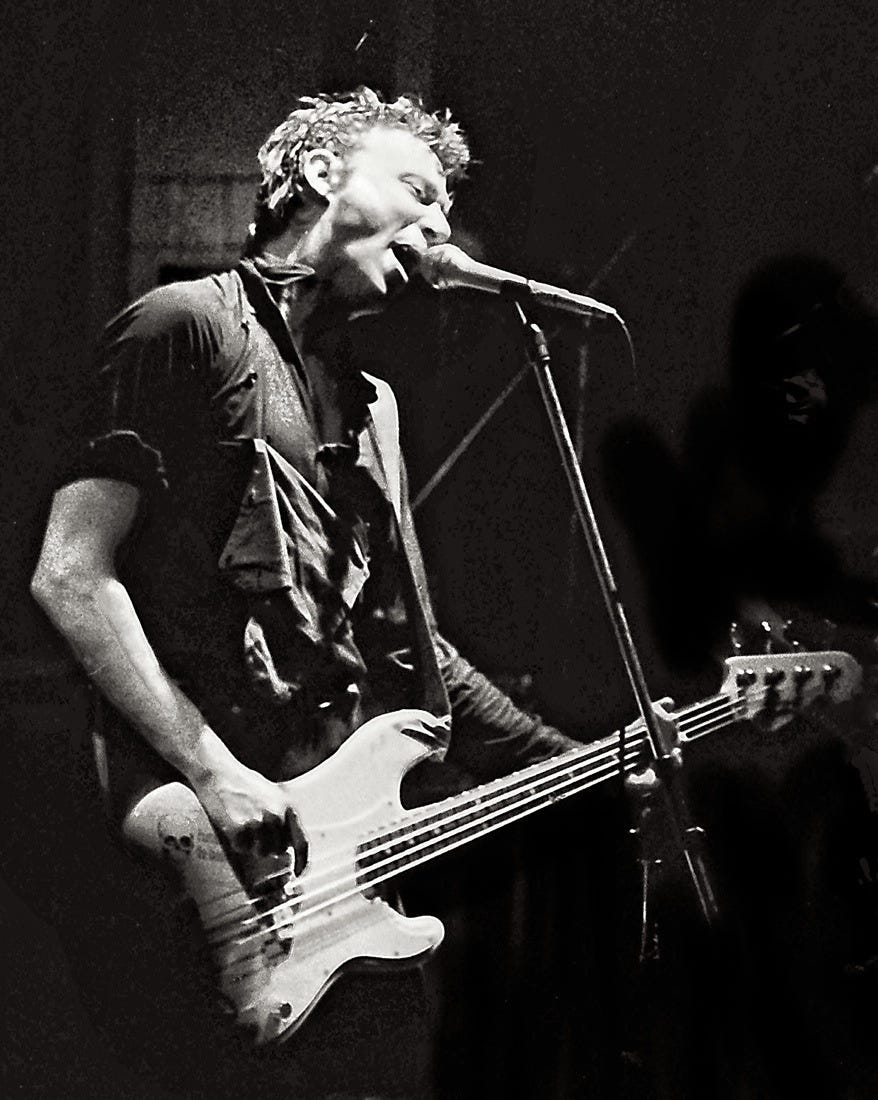

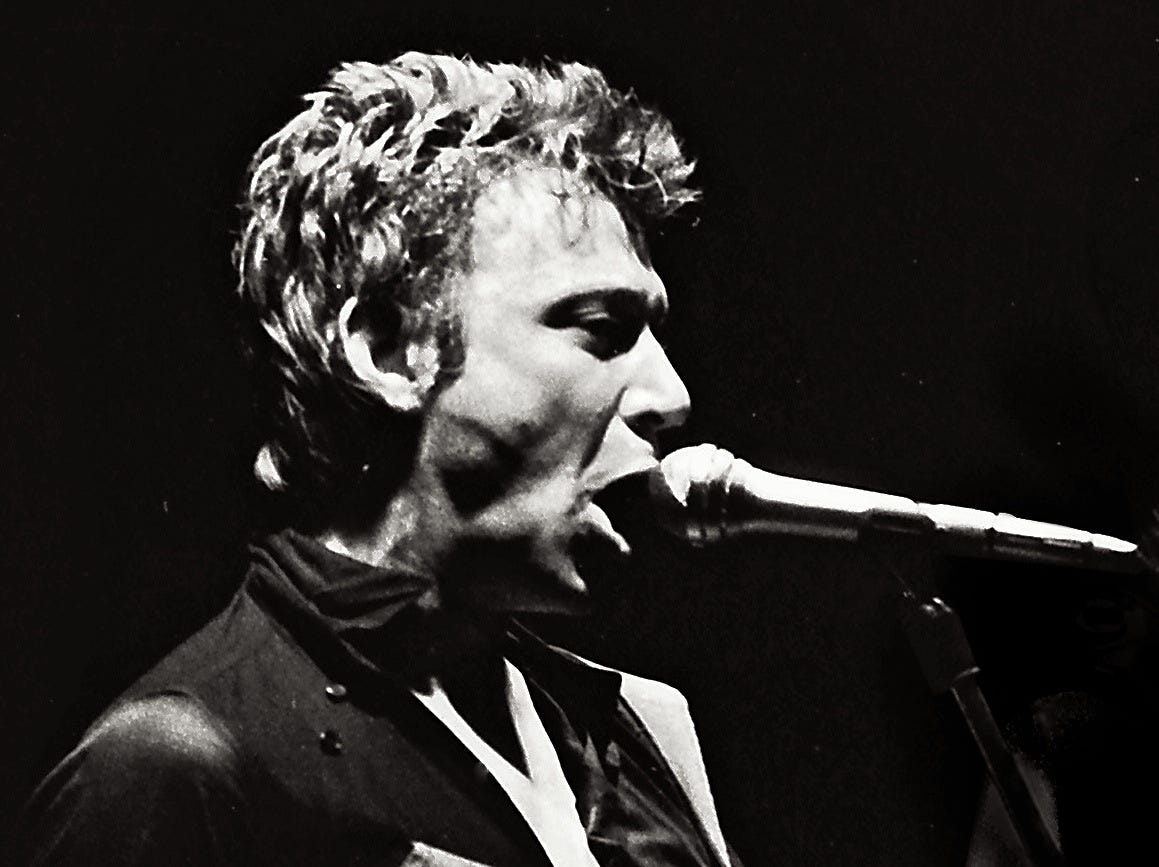

Photos of Richard Hell onstage at Markthalle Hamburg in Hamburg, Germany, 1983 by txmx 2 via Fickr

Great stuff 👏