See what’s right, see what’s there

Reflecting on a lovely song, and some practical advice, from Paul McCartney

After visiting my dying father in Maryland, scrambling with my brothers and my sister and my mom to assess and meet the thousand mind- and soul-numbing details of planning a funeral mass and an entombment, laying my dad to rest on New Year’s Eve, flying home, and continuing to attend, frustratingly from afar, to my mom’s needs, all while grieving, I naturally caught a wicked head cold, which has only added insult to injury. Amy and I are both laid up, but coming around. As the spring semester of teaching looms, I’m slowly working out of it toward some semblance of normal, whatever that is, as events beyond my control continue to spiral.

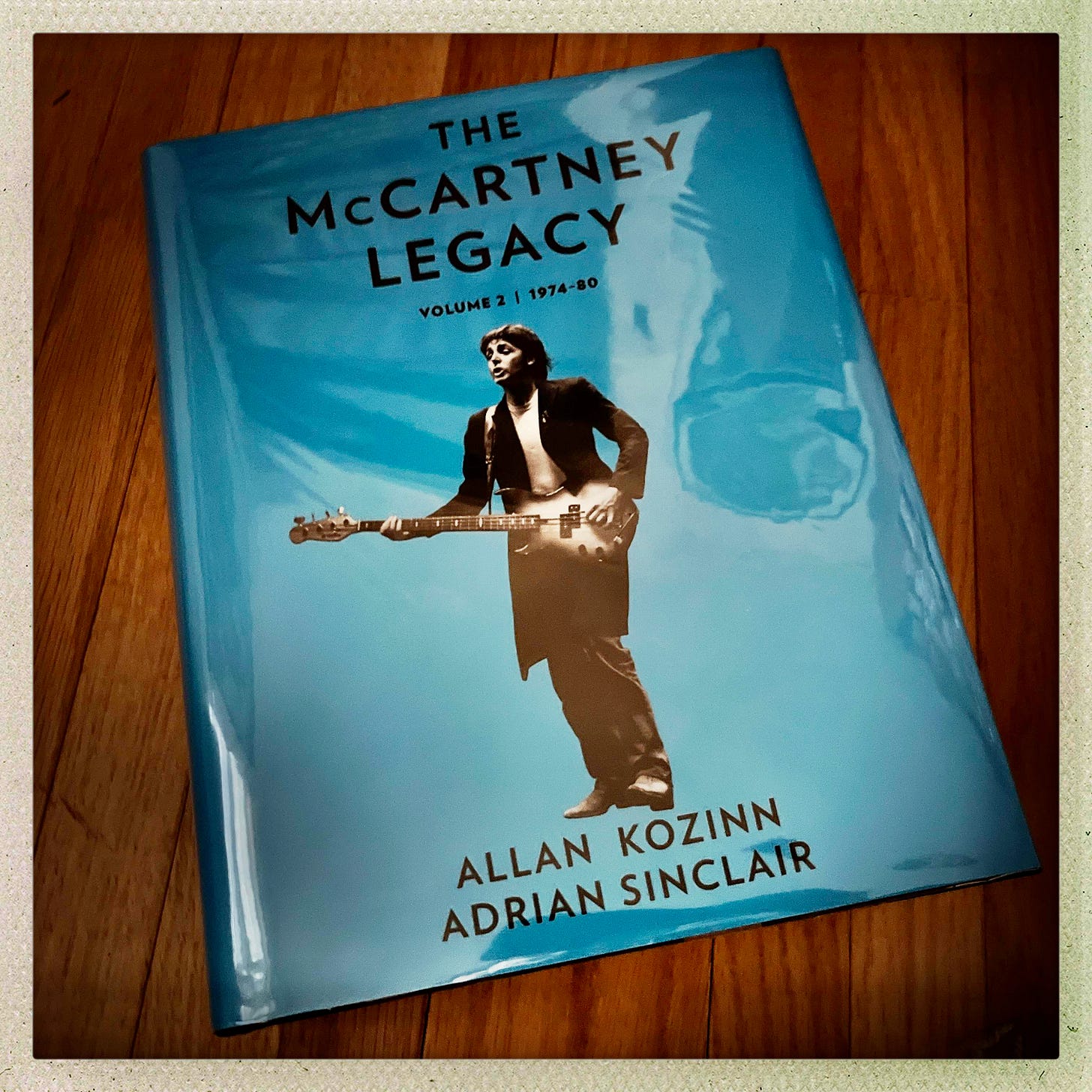

My comfort reading through all of this has been Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s The McCartney Legacy, Volume 2: 1974-80, the 750-plus page second installment of their massive, multi-volume Paul McCartney biography. I gobbled up the first book when it was published in 2022, relishing and marveling at the astonishing levels of research and synthesis that the authors achieved. They’ve interviewed everyone (excluding Sir Subject) and, between the two of them, appear to have read/listened to virtually every McCartney and McCartney-adjacent book, article, interview, podcast, press kit, liner note, and social media comment, and though the book’s details get awfully micro in places and aren’t always particularly worthwhile, the overall impression after I put down the first volume—I’m two-thirds of the way through the new book—was of having been a member of an inner-circle of sorts, intimately close to McCartney as he lived out both his personal and professional lives. I feel as if I’ve read a hefty, durable, detail-rich novel, and if Kozinn and Sinclair’s combined writing style doesn’t evoke much beyond on-the-ground facts or aspire to be especially literary, their dogged research and ambitious, balanced, wide-take approach in sifting the details for the story more than make up for that.

In the fall of 1977, McCartney was in Abbey Road Studio applying overdubs and finishing touches to “Mull of Kintyre,” what would soon become one of the biggest selling pop singles in U.K. history, as well as readying the release of Wings’ new album, London Town, which would come out in March 1978. In October, he was visited in Studio Two by Melvyn Bragg, a well-known BBC arts reporter who was helming a new program for ITV, The South Bank Show, which aimed, in the egalitarian spirit of the times, to blend high art and low art for a large audience. (A popular success, the show ran from 1978 to 2010; in 2012 it was supplanted by a new version on the Sky Arts channel. The series ended in 2023.) McCartney would appear in the program’s inaugural episode.

I found video of the interview on YouTube as I wanted to watch a scene that Kozinn and Sinclair relate in their book. McCartney’s sitting at a piano; Bragg’s perched on a chair next to him. McCartney, in one of those classically charming yet genuinely revealing moments, describes his songwriting process, arguing that there’s a bit of magic involved, yet insisting, in his Northern, untutored way, that it’s easy to start a song, really, and that anyone can do it. He turns to the piano, plays a simple three-chord sequence on top of which he lays a little melody and lyrics about his host, Bragg, drinking tea in the parlor. The moment feels unscripted, and given McCartney’s melodic gifts and his unending enthusiasm to share with others, the spontaneity seems more than plausible. Anyway, the moment’s terrific.

I kept watching—seeing McCartney do most things is catnip to me—and a bit later in the conversation, among the more standard questions and answers, Bragg asks McCartney why he felt compelled to get back on the road after the Beatles broke up in 1970. “I don’t know, don’t know,” he responded. “I think it was because I was feeling like the longer I waited, with another day of no work, another day of nothing to go to, the more I was just getting stagnant. It was a bit like, sort of, after an operation. You want to rest, but you’ve got to push it ‘cause your body’s just gonna go downhill all the time, you know. I just had to push something. And so I just thought, Well, you know, the man who sings every day is gonna have a better voice because he’s practicing every day.” He added, “It’s got to be good for you, that. Kinda just get out and do it.”

Normally, McCartney’s grinning, thumbs-up, can-do optimism can rankle, an outward P.R. manifestation of his more mawkish or shallow songwriting; a seasoned pro, he can switch his cheeriness on and off with clockwork efficiency, and it’s often difficult, particularly in promotional interviews, to sense when he’s being sincere, or, I guess, unguarded. But by all accounts he is a natively positive person, and, perhaps given that my defenses, via grief and this virus, have been brutally lowered, I found McCartney’s practical advice inspiring and moving. I’ve been having difficulty getting back into gear after coming home from Maryland, depleted and reckoning with losses both personal and universal. Turns out that what I needed to hear was a bit of Dad McCartney dispensing some wholesome encouragement. Remarkable when something that might sound corny and clichéd one day can sound profound and wise the next.

In the event, I flashed on to a small something I wrote a decade or so ago about McCartney’s sublime cover of the Vipers’ “No Other Baby,” from his 1999 album Run Devil Run, the first album he made after the death of his wife Linda, an album that he made because of and for her.

No Other Song

I flashed on to a different song, also. In the summer of 1979, a year and a half after he spoke with Bragg, McCartney was fooling around in his home studios both at his farm house in Scotland and his country residence in Sussex, England. One afternoon, a Hare Krishna devotee appeared at his doorstep. (In McCartney’s telling, it’s unclear whether this occurred in Scotland or England, though given the remoteness of both residences it might’ve happened in London at McCartney’s Cavendish Street home.) “He was a nice fellow, very sort of gentle,” McCartney said. “After he left, I went to the studio and the vibe carried through a bit. I started writing something a bit more gentle that particular day.”

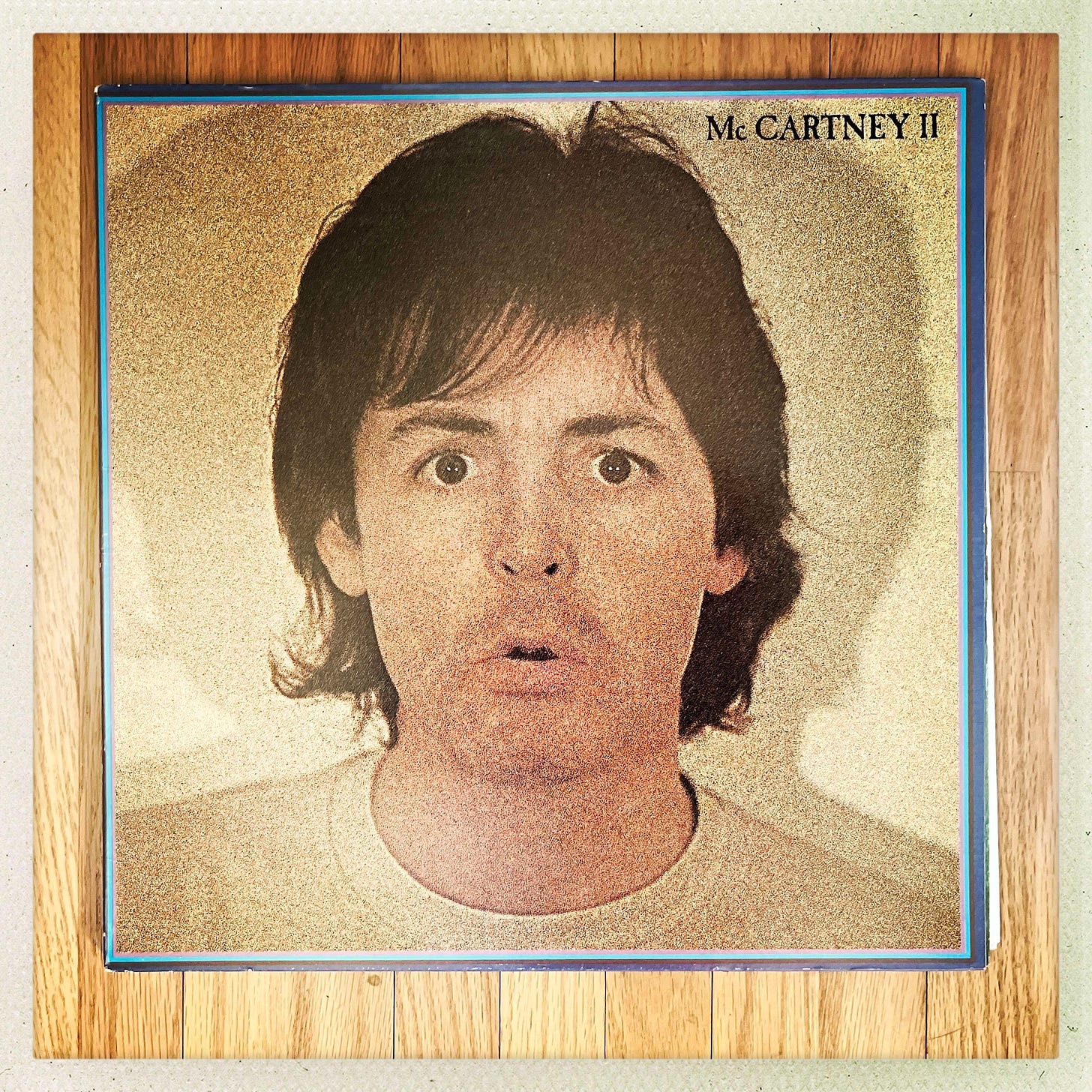

What he wrote was “One of these Days,” which would appear on McCartney II in 1980. It’s one of McCartney’s finest songs to my ears, a lovely, hauntingly simple declaration of resolve, the sonic equivalent of the calm that settles after a deep, cleansing breath. Charmed and probably moved by the Hare Krishna’s affect, a seriousness of purpose that was offered politely, McCartney responded in kind, reflecting on how personal difficulty is best addressed with clear and simple means, with clear ideas and clear intentions. And in McCartney’s case, with a clean melody, played and sung on an acoustic guitar. Harmonies sweeten things on the final lines of the verses and there’s a bit of guitar filigree in the second bridge, but the central pleasure in “One of these Days” is the vocal, sung characteristically sweetly and with reverb that lends an eternal quality to the melody, as if we’re hearing a song being sung a thousand years ago, arriving today as by starlight, or some small miracle.

“One of these days, when my feet are on the ground,” he sings, the melody descending (rare for McCartney) and then rising in the next line, “I’m gonna look around and see,”

See what’s right, see what’s there

And breathe fresh air ever after

Elemental stuff. (Simple, really, he’d say.) When a job takes too long—writing a song, mending a fence, worrying a relationship, whatever the task is—he’s going to sing a song to see what’s right and what’s right there, and to remind himself to breathe. McCartney sings “One of these Days” as if its insights have deeply, genuinely pleased and affected him; this is no quirky novelty or made-to-order song. The bridge—

It’s there, it’s round, it’s to be found by you, by me

It’s all we ever wanted to be

—reminds us that this is a love song, too; its composer’s always been eager to share his adoration and marveling of the world with his loved ones. Which, given McCartney’s populist impulses as a songwriter, can include us, too. “Nothing pleases me more than to go into a room and come out with a piece of music,” he once remarked, recognizing, I think, that a song like “One of these Days” is a gift for its listeners as well as for its composer. (He understood the song’s serene wisdom, choosing it as the closing track on McCartney II.)

“The song seemed right as a very simple thing,” he said, “and it basically just says, ‘One of these days I’ll do what I’ve been meaning to do the rest of my life’. I think it’s something a lot of people can identify with.” During this rough patch, I certainly do. The song has come to me at just the right time.

See also:

Joe, I haven’t had to chance to read this post in its entirely yet. But I just wanted to say, as a subscriber and someone who’s even bought an essay collection directly from your hands, that I wish you peace and comfort. And strength.

Hope you feel better, Joe!

Lovely piece.